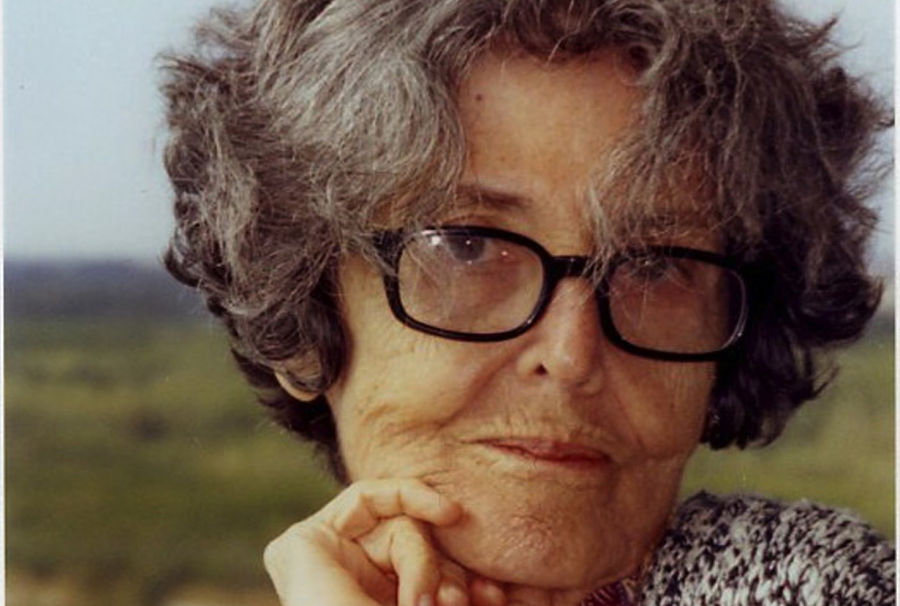

Playwright and teacher Maria Irene Fornés died on Oct. 30 at the age of 88, leaving a legacy that includes the plays Fefu and Her Friends, The Conduct of Life, Sarita, and Abingdon Square, as well as countless students who credit her with changing their lives and the aesthetic possibilities of writing for the American theatre. This is one of three memorial tributes to the influential writer; others include one from Migdalia Cruz and one from Caridad Svich.

She always seemed small to me. But of course, like everything with the wonderful doyenne playwright, Maria Irene Fornés, she could make you believe in all things imaginary.

As one of the leading figures of the off-Off-Broadway movement in New York, as a well-regarded experimental playwright, an important generation influencing teacher, this Cuban American avant-garde writer brought a great deal of idea and investigation into the Room.

The Room. I remember it well. I was one of those lucky many who got to study with La Maestra Fornés, and it changed my life. The Room was almost religious sometimes. Listening to thoughts from Irene on approach, the surprise of writing, a journey into the unknown and the exploration of one’s own surprising id. A little bit of yoga, some visualizations, writing with prompts and then reading. Never less than three hours, but it always felt too short.

I believe the genius of Irene in the Room was her intuition, her ability to spark something in you around letting go, running away from “good” ideas toward authentic and surprising ones that were more enduring. “Someone has entered the room. Do you recognize this person?” Often, I wanted to scream out, “No, and it’s me!”

A good deal of the Fornés workshop was spent on getting out of the way of your own work. I can still hear Irene’s urging after a prompting question, “Don’t choose—the first idea that hit you is the best, who knows why.”

When I studied with Irene in Los Angeles, through the generosity of Gordon Davidson and the Mark Taper Forum, her mother was still alive: Carmen, who passed at 103 years young, doted on by her talented, loyal daughter. We would line up chairs to make a bed of sorts and Carmen would lay down and listen. One time I wrote something funny and Carmen laughed from off in the corner and Irene looked surprised, eyebrows raised, and said in her trademark accent and girlish voice, “Oh my goodness, you’ve made my mother laugh. Very good…” She sounded like a character in one of her plays.

I have so many memories of my great mentor and teacher. She spoke differently to me when we spoke Spanish. As if one traveled farther back in time with her you became family. I remember a conversation once about my political activism that could have only happened in Spanish because for me it seemed so vulnerable and pointed. La Maestra was intrigued and fascinated by the idea that I would go out in the middle of the night all over Los Angeles in a paper suit, and someone would spray paint the silhouette of my body on a sidewalk, calling attention at the time to the murders of innocent people during the civil war in El Salvador. I would leave a ghostly image.

“You have an interesting voice as a writer, but you have so many concerns…” She let the sentence linger in space, almost urging me to catch it. She would continue, “Perhaps you should focus passionately on one, your politics for one, and then come back to writing. I promise you, write about anything, a rock, and it will be political. Let things live in you…”

I took all her advice to heart, but she would caution, “I could be wrong, Luisito. But I don’t think so.” She never was.

Her obsessions were always so interesting. Once I invited her to a Latina variety show I produced at the Mark Taper Forum, and she was mesmerized by a flamenco dancer. She insisted on meeting the troupe afterward. “I must know how they did this thing, this magic. They conjured. I am in a spell.” Yes, she was dramatic, but never not honest about it.

When I see her now, I can picture her trademark look: black slacks or skirt, a white blouse tucked in at the waist, which she would pull out for the yoga stretches, the ritual of watching her roll up of her sleeves, the literal and metaphorical action. Sometimes she wore a beret. It was the outfit to come into the Room with. To do the work.

In 1999, we saw each other at the Signature Theatre during a retrospective season that included a last new play, Letters from Cuba. I knew I had to get myself to New York for this culminative moment, and I don’t think I saw a finer production of her seminal play, Mud, anchored with an extraordinary performance by a frequent Fornés collaborator, the actor Deirdre O’Connell, who gave such a powerful performance.

There was a panel discussion around Irene’s work that included her beloved students, Migdalia Cruz and Nilo Cruz, as well as Irene’s agent and caretaker, the great dramaturg Morgan Jenness. The audience included so many of her celebrated students, including Caridad Svich, among others. It was a very special evening and Irene was beaming at the attention. I remember when she entered the room, anchored on someone’s arm, and smiling with anticipation as she found a seat. She sat rapt in the audience, listening and interrupting to speak when someone stumbled on a fact. It was her night and she was going to interrupt it if she pleased.

When I last worked with and studied with Irene, the ravages of Alzheimer’s had not yet set in, but you could see the beginnings; she had already become very forgetful. In 2003, my creative partner at the Taper, Diane Rodriguez, and I brought Irene out to Los Angeles for a powerful gathering of Latinx theatre artists in Los Angeles. A conference and community building event that culminated in a workshop led by La Maestra. We broke bread. We listened to new work. We had panels. I rented a van and put everyone up at a hotel in Pasadena, about a half hour from downtown Los Angeles. The morning of Irene’s workshop I was awoken by a call from the hotel telling me she had checked out of her room. I panicked, and maybe I knew then that this was going to be one of the last times our dear mentor would travel or teach. I raced over to Pasadena, maneuvering the curves of the oldest freeway in the state, in the rented van.

Irene was nowhere to be found. I was afraid to tell everyone for the panic that might set in. I ran around the hotel like a madman. I felt ridiculous, out of breath and in tears. Finally I found her outside, standing next to the pool, her suitcase at her side, fully dressed, her little hat on and wearing her New York coat. She looked like a Magritte painting.

I steeled myself so as not to alarm her. I approached and took her hand and she asked me if we were in Cuba. She asked with such innocence and charm, it calmed me. I could never tell how conscious she was about losing memory.

I calmly told her we were in Pasadena and that she was going to be giving a writer’s workshop in a few hours, if she felt up for it. She looked at me surprised and said, “Of course!” I told her we needed to check into the hotel. She was very calm and spoke, in her Irene way, “Very well, very well…”

We got back into her room and she said, “Oh my goodness! I recently stayed in a room just like this one!” I didn’t have the heart to tell her it was, in fact, the same room.

I was so emotional that last day. She gave a marvelous workshop. I think everyone in there had some special relationship with Irene. She looked at the room and it seemed like everyone represented a different moment in her life as a teacher. No matter when one had encountered Irene or studied with her, it was clear, we were back in the Room.

She began with some thoughts about writing, and they were astute as always. It was an amazing day. I had not thought about the profundity of Irene’s effect on my life and art, maybe until that weekend. This tremendously talented writer, with a process that could unleash wonderful creativity and original writing, who sat patiently in the room while we wrote furiously. Sometimes I would look up and we would make eye contact and she would look at me, as if to say, “You can do it, don’t stop, you are discovering!”

The next morning, we got to the airport. Eduardo Machado and Jorge Ignacio Cortinas had arranged to place Irene between them on the plane on their way back to New York. I know this might seem selfish, but I was fretting on our last day together about whether La Maestra would remember me. Her mark on me was so indelible, I yearned to give the gift back to her.

In that last drive to the airport, I could see myself on the first day of the workshop when we first met, in the room with other important Los Angeles writers: Leon Martell, Alice Tuan, Bridget Carpenter, Cherylene Lee (RIP), Han Ong, Lynn Manning (RIP), and Naomi Iizuka, among others. I thought of this gathering, this final workshop, as a kind of goodbye. Maybe I was intuiting it, as we did with our work in the Room. I could sense a fragility setting in Irene, much as we witnessed in Carmen so long ago. How funny that I had not noticed: She was wearing a beret, just like her mother used to wear.

We stood outside of the terminal, hugging generously like we Latinxes do. Laughing, giving our goodbyes, promising to keep in touch and get back to each other’s cities soon enough.

When I got to Irene, she reached out and held my face in her hands. She called me by the name she gave me when we spoke Spanish, Luisito. She gave me a kiss on each cheek and said, “I remember you.” Looking deeply into my troubled smiling face. “I remember you…”

It was the last time we spoke.

Luis Alfaro is a Chicano performance artist, writer, theatre director, teacher, and social activist.