As a lighting designer who often uses haze (and sometimes doesn’t), I want to respond to Williams Youmans’s recent article (“A Hazy Shade of Theatre: The Case for Clearer Design), which really paints lighting designers in an unfavorable light. (Bonus points for a pun?)

I realize it was meant partly as a humor piece, but while we can all stand to take ourselves less seriously, we take our work and our craft very seriously. I’ve enjoyed Bill’s stage work over the years, but this seems to me an odd topic for him to write an op-ed on. It would be a bit like me writing a piece suggesting performers use less vibrato or pick up their cues. I might have an opinion on these, sure, but it doesn’t really feel like my place to give notes on how other artists create their work.

But he did write it, and by no fault of his own, the timing is somewhat unfortunate. Designers all over the country are fighting for credit on multiple levels: on theatre websites, press releases, reviews, articles that feature photos of our work, even in this magazine. We are in a constant battle for respect and recognition and are always trying to better educate the public about what we do (help tell the story, convey emotion) and what we don’t (we are in fact, not the backstage crew). And let’s not forget those couple years the Tony Awards felt sound design wasn’t an art. So if my response seems a bit disproportionate, it’s only because it touched a nerve.

This article was bizarrely included in the latest issue of American Theatre, featuring articles on lighting design and the virtues of that particular design discipline. An accompanying piece this condescending toward that same industry only serves to discount the good reporting done in those pieces. To that end, I would like to address some of Youmans’s points:

- “Stage ‘fog’ is generally of two kinds: Let’s call them ‘fog’ and ‘haze,’ respectively.” I’m not here to quibble over semantics, but since he brought it up, yes: Haze is the atmosphere that hangs in the air. Fog generally refers to low-lying fog that hugs the ground, and there is also smoke (think of the Wicked Witch melting). I only bring up the terms because later in the article he says that “stage fog has been essential in every production with the budget to afford it.” That is obviously not true. Perhaps he means haze in this case? I can’t remember low-lying fog in any of the recent productions of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?. If we’re going to define the terms, let’s use them correctly and be consistent so we’re all on the same page. I’m only discussing the use of haze in the following.

- “I always thought light was supposed to illuminate the thing being lit, not draw attention to itself.” This is a bit of outdated thinking only held by those who still view design as a secondary art form. There are certainly shows where you shouldn’t notice the lighting. But the generalization that lighting should never really be noticed is archaic and narrow-minded. Great theatre artists understand that every design element—set, lighting, costumes, sound, projection—work in service to each other and the text to help tell a story. Sometimes that means the lighting should be purely utilitarian. Sometimes it means the lighting should be completely divorced from the action onstage. Sometimes it means the lighting and scenery function as characters in themselves. But the notion that each or any of these elements, no matter what the piece, should always perform a specific function isn’t just outdated thinking—it’s destructive to a collaborative process. Consider some of the recent Tony winners for lighting design: There was the beautifully understated The Band’s Visit (Tyler Micoleau), Indecent (Chris Akerlind), and Once (Natasha Katz), the technically jaw-dropping Harry Potter (Neil Austin), the lush and painterly South Pacific (Don Holder) and American in Paris (Natasha Katz), and yes, the high impact and flash of Great Comet (Bradley King) and Hedwig (Kevin Adams).

- “But I have never met a director who wasn’t at least a bit enthralled by gorgeous gestures of light…” I would tend to agree. And let’s remember that aside from helping tell the story, the designer is there to help shape and realize the director’s vision. We often love large lighting gestures because directors love large lighting gestures, and we like making our directors happy and creating for them the show they see in their head. If they were concerned about lighting distracting from their play, I’m sure they would be the first to speak up.

- “You can’t just have [haze] in one scene for which it might be appropriate—a rest stop outside a power plant on the New Jersey Turnpike, say—and then clear it in time for another scene where it might not be, like on a desert plateau in New Mexico.” This is an extremely literal way of thinking about haze, something we rarely do. Lighting designers (and by extension our lights) don’t just tell the audience, Where are we and is there a smoke stack nearby? We also help convey the feel, smell, taste, tone, and personality of any given scene. To me, a desert is dry, dusty, hot, and sandy. A sense of atmosphere helps convey all of that and transport the audience. Hot and relentless sun is assaulting. If you can practically feel (by seeing the atmosphere) the oppressive wash of light beating down on the characters, then we have helped tell the story.

Contrary to the impression Youmans gives, lots of shows don’t use haze at all. And lots of shows definitely shouldn’t have haze. And yes, there are undoubtedly high school productions of The Music Man that feel like the launch of Apollo 13. But haze, when appropriate, is a powerful tool that serves multiple functions. Light is inherently invisible. When a beam comes out of a fixture, you will only see that light when it A) hits an object like a person, scenery, or floor or B) you see it reflecting off of particles in the air. Many if not most shows often have limited resources. Not enough scenery, cast too small, small amount of lighting fixtures, etc. When you want to make a big impact with lighting if you have nothing to light, then the impact of the cue is minimal, especially for those audience members who can’t see the floor.

So designers often consider “air architecture.” It’s a way to create something out of nothing. Haze allows the lighting to make the stage feel fuller. It helps fill in the gaps made by small budgets. When a director says, “This cue needs to feel bigger,” they are talking about contrast, the difference between Point A and Point B. If you can see the beams move, or change color, or turn on, it’s a more dynamic action, thereby making the moment feel stronger. A lone performer on an empty stage with no haze feels very different than that same performer with a shaft of light backlighting them from the high corner of the back of the stage, barreling its way down to the back of their head. The decision to make that beam visible says something, makes you feel something different, and reconfigures the space in a completely different way. The geometry of the space is always something designers are considering.

Believe it or not, haze can actually assist the performers in garnering more applause. It’s like an alley-oop from a great point guard. Ask any lighting designer who’s been forced to sit through a show where the haze wasn’t working (as I did recently on an opening night at the Kennedy Center) and they will tell you it feels like half the energy has been sucked out of the room. Big musical theatre buttons, key changes, and builds are accented and punctuated by lighting (along with musical dynamics and orchestrations). If you see those visual accents at the same time you hear them, it’s that magical combo that makes the hairs stand up on the back of your neck.

Just think about the final image of “Defying Gravity,” Kenneth Posner’s hazy beams all ablaze, and then the intensity in which the blackout slams in on the musical cutoff, or the final moment of “The Room Where it Happens,” when Burr is left alone down center in a single white backlight, snapping even smaller with the gun click button (design by Howell Binkley). Those visible beams make big theatre moments feel even bigger and make an audience rise from their seats. We’re not showing our work to distract; we’re there to propel the performer to the ovation they surely deserve.

Directionality is one of the main properties of theatrical lighting, and we think a lot about where light comes from. Consider Hal Morey’s famous Grand Central Terminal photo, with the shafts of light streaming through the window. The only reason that photo has become so iconic is because of the strong (and visible) directionality of the light source. It elevates the photo to something ever greater. Of course, not every scene calls for “Game of Thrones”-style shafts of light. But having a sense of the source of the light often helps tell the story. Is it the sun, the moon, an offstage room, a lighthouse, a spaceship, a candle? When you can’t see where the light is coming from, we have less access to directionality as a tool in our arsenal.

Visible beams can also help draw the eye of the viewer. Film and TV have the camera lens to tell you where to look. In theatre, the audience can choose to look anywhere. Great care and attention by the director and the designers is placed on telling the audience where to look. Every good stage picture should tell you where the focal point is. The use of haze can act like a camera lens: panning, tilting, and zooming, leading the audience to focus on exactly what we want, and telling a clearer story.

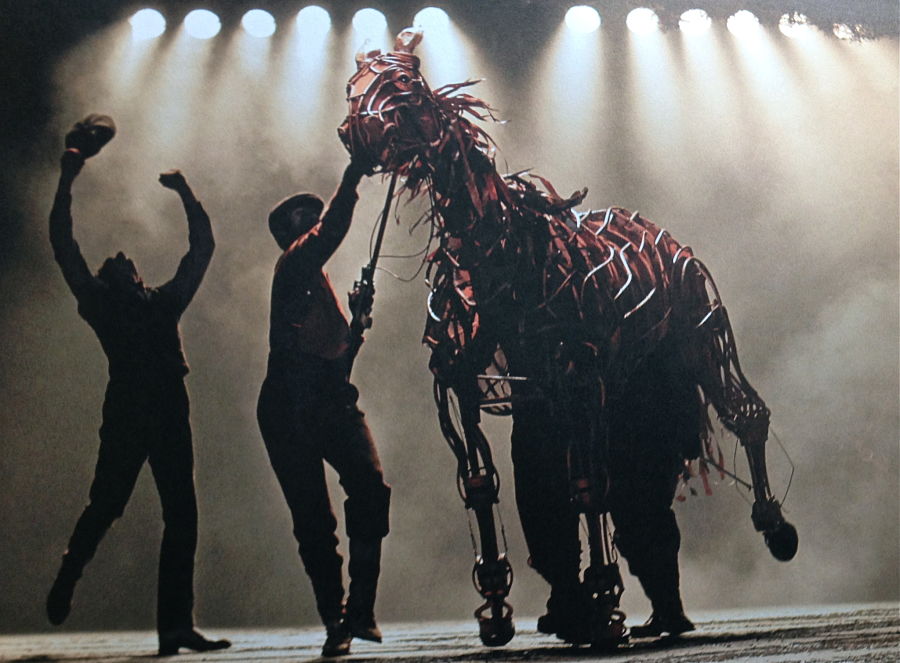

Sometimes haze is used to intentionally conceal stage business. Paule Constable’s use of haze in War Horse and Angels in America, or Neil Austin’s deft use of it Harry Potter, allows characters to slip in and out of the stage picture. The haze creates a “gauze,” as Youmans mentioned, allowing greater control of what the audience does and doesn’t see, thereby creating magic right before your eyes. If there is a more breathtaking moment onstage of seeing young Joey turn into an adult horse through a thin wall of atmosphere, I’ve yet to see it.

Haze can also be crucial in productions performed in a thrust space or in the round. As these shows often have little or no background, the “background” is sometimes just the audience on the other side. There is nothing worse than watching Desdemona pour her heart out while a guy on the other side of the theatre checks his text messages. The use of haze in these spaces creates a virtual backdrop. It puts a layer of light between the stage and the opposite audience and keeps your attention drawn to the stage. This can be seen in practice in the current production of Once on This Island (lit by Jules Fisher and Peggy Eisenhauer) or in the recent production of Fun Home (lit by Ben Stanton), both performed in the round at Circle in the Square.

As you can see, there are many uses for haze, and we spend tireless hours trying to dial in just the right amount. Keep in mind that this can be extremely difficult in theatres where the air temperature and current is impossible to replicate unless you have a full house of warm bodies. The use and amount of haze is thought out and considered. It may not seem that way from the other side of the footlights, but it’s a design tool to be wielded with great care, just like anything else.

An opinion piece about haze use peppered with some light humor and industry jokes would not normally merit a response of this length. But in the context of all the other ways our work is being marginalized, and all the ways we keep having to stand up for ourselves, it takes on greater significance when we are told how we are doing our jobs thoughtlessly. This article paints all lighting designers with a broad brush, making them seem lazy, ambivalent, and unoriginal in their use of haze, and even seems to suggest that we might be working against the performers and distracting from their work.

Lighting designers are by definition and practice collaborative artists. We cannot work on our own or in a vacuum; we are wholly dependent on bodies in a space before we can begin to work. We are there to assist and elevate the work onstage, and make sure the audience walks away with a night that will stay with them. In a time when the arts are being attacked by an administration that would rather see more troops than trumpets, we all need to stick together and lift each other up. I’m all for having a good laugh at the expense of podiatrists, professional curlers, or yacht owners, but the theatre community is a small and tight-knit group, and this article, however satirical its purpose, feels like it’s punching down on some of our own. Let’s save the criticism for the people and organizations interested in keeping us down and try to respect and support those in our own community a little more. If you want to create a better “atmosphere” onstage, that feels like a good place to start.

Cory Pattak is a New York City-based lighting designer and host of the design-themed podcast “in 1.”