Students at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School have been through the unspeakable. But in the wake of the mass shooting at their school in February, many have found new platforms for their voices. And some took a break from the world stage to the stage of the Boca Black Box theatre, where they performed Spring Awakening last week (May 2-9) with the local training and production company Barclay Performing Arts.

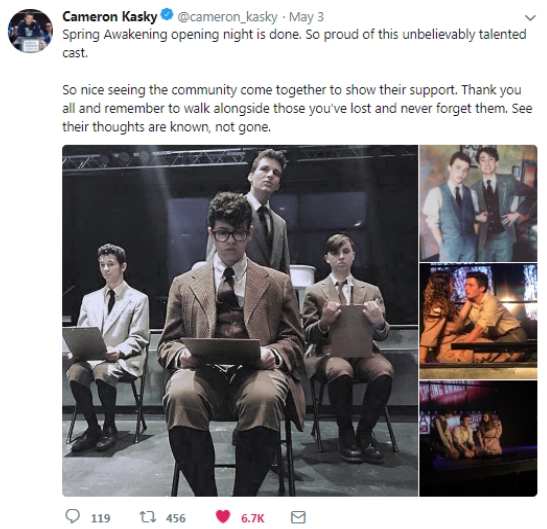

A third of the show’s cast were students at MSD, and the show’s leads have been vocal leaders in the aftermath of the shooting: Cameron Kasky, the show’s Melchior, co-founded the #NeverAgain gun control movement with Alex Wind, who plays Hanschen. Sawyer Garrity, who portrays Wendla, co-penned the song “Shine” with fellow classmate Andrea Peña, which saluted the resilience of the MSD community. The “Shine” music video was released earlier this week and already has more than 42,000 views.

As a high school musical theatre kid myself, I remember standing in the wings during tech rehearsals with flashcards anxiously studying for midterms between scenes. But these MSD students had far more to juggle than just school assignments, as rehearsals for Spring Awakening were interrupted by rallies, by the March for Our Lives event in Washington, D.C., even by a visit to the Time 100 gala in New York City.

This production also received more outside attention than any of my own fledgling efforts, with some members of the musical’s original Broadway cast flying down to Boca Raton to lead workshops with the students during rehearsals. Theatres from around the world sent letters of support, and other high schools across the country who were also mounting Spring Awakening sent videos to honor the Florida cast.

But it wasn’t just the students’ involvement with #NeverAgain that garnered global attention for the theatre production—it was that the show’s themes of adolescent angst and generational misunderstanding dovetail eerily with the students’ own harrowing experience. Duncan Sheik and Steven Sater have said that their 2006 rock musical, based on the 1891 German play by Frank Wedekind, was in part inspired by the 1999 mass shooting at Columbine High School. The coming-of-age tale follows a group of teens as they discover sex, experience the loss of friends, and fight for adults to listen to them.

High school musicals are a special kind of theatre event. Months of rehearsals lead to a short run of performances, and the opening-night jitters jumble with mourning the end of the whole experience. This one was no different, though there were some new wrinkles. On opening night, as a line of people formed outside the unassuming venue in a shopping center with an Office Max and Burger King, the crowd bottlenecked as a police officer performed a bag check at the entrance. Parents of the students held court on the sidewalk at a merch table of sorts, selling Shine MSD T-shirts bearing the phrase “Together we will shine the light.” The Shine MSD organization, named after the song “Shine,” raises relief funds for the victims’ families and supports mental health programs centered around the arts in the community. I bought a shirt from Garrity’s mother.

A sort of muddled energy of anticipation and possibly dread was in the house as audience members took their seats. The Boca Black Box is essentially a concert venue, and servers swirled the rows of seats and tables throughout the dark space with trays of drinks. I was seated at a table with Sheik and Sater, and suddenly the unidentifiable energy in my own body rose as excitement, as my feelings about watching the performance escalated to a new level: I would be watching them watch the show.

Sheik and Sater had already begun the emotional ride that afternoon, when they traveled 10 miles south of the theatre to visit the students of Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School. The drama teacher gave the composer and playwright a tour inside the school, with its boarded-up windows. She turned off the lights and led them to her office where she sheltered 65 students on the day of the shooting. “It was harrowing, to say the least,” Sater told me.

Still, he said, being surrounded by a group of theatre students that afternoon, Sater felt a sort of nostalgic comfort. “I was a theatre kid in high school, and I kind of discovered myself through theatre,” he said. “So I am always in a certain space when I am sitting with a whole bunch of theatre kids.”

The students did not want to discuss the shooting, so the authors talked to them delicately about the origins of their musical, and its relationship to Columbine. “Clearly a kind of hush fell over them and they felt it in their hearts—what a journey it has been,” he said. “It was very moving.”

For these students, the show contained and expressed many of these feelings; indeed it seems to have been designed to hold them. It became a kind of vehicle for the students—a fast-moving train headed toward a place close to healing. The show’s enduring message of the power of young people struck, and still strikes, a resonant chord.

“You know, we didn’t create a show like Wicked or The Book of Mormon that is still running,” said Sater. “But we created a show that lives on in memory and has had a big impact on a lot of people.”

I confessed my own small connection to the musical: I auditioned for the role of Wendla for the show’s pre-Broadway run at the Atlantic Theater Company in 2005. I was 13, and I sang Aerosmith’s “I Don’t Want to Miss a Thing.”

“I thought you looked familiar,” joked Sater.

The house was held for 20 minutes, adding to the palpable tension already in the room. Music videos from the ’90s played on a grid of 9 screens above the bare stage. Sheik and I giggled watching Christopher Walken dance in Fatboy Slim’s “Weapon of Choice” video. I wondered whether the lineup was intentionally selected to ease the pressure, or if it was just the venue’s usual pre-show video. It worked, temporarily.

The show’s director Christine Barclay then addressed the crowd with some announcements. “There were some disclaimers that were posted, and there was one that said that there would be a gunshot in the show,” she said. “I’m here to tell you that as a creative team, we have decided that there will not be a gunshot in the show. You will not be wondering when that will happen, you can relieve yourself of that—it won’t happen.”

The room let out a collective breath of relief. “Part of me feels like I’m not emotionally prepared for this,” confessed Sater as the lights dimmed. I don’t think anyone could have possibly been emotionally prepared, not even a little bit.

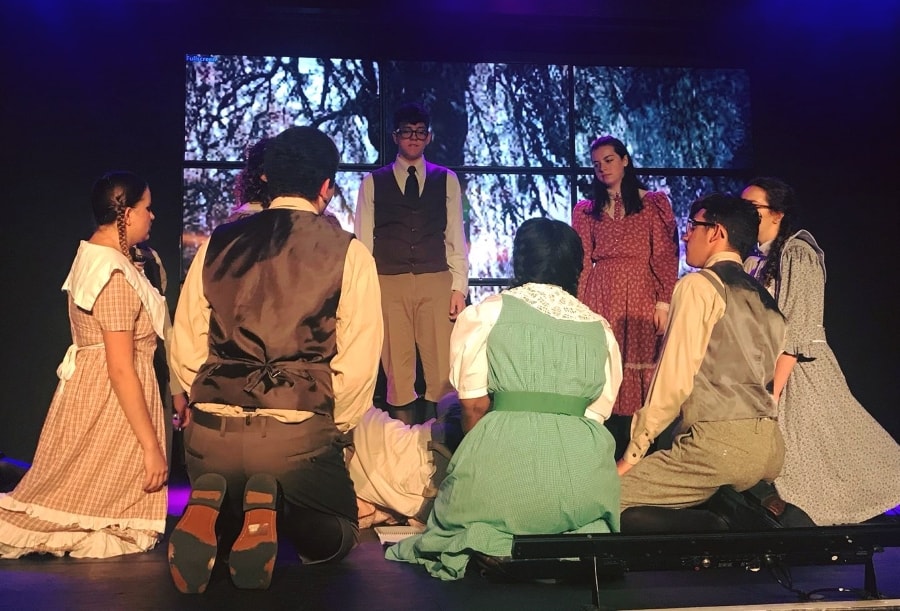

The 9 screens above the stage served as the show’s set, cycling through images of a flickering candle, a budding tree, and a graveyard. I heard someone whisper, “Where’s the band?” There wasn’t one; a pre-recorded track boomed through the speakers. Occasionally a “loading” signal would circle on the screens during scene changes. I saw a crew member use their cell phone flashlight to light the aisle for cast members to make their entrances and exits. It all added to the excitement of opening night. Despite the technical glitches, the students gave a first-rate performance, diving head first into the show’s edgy moments and falling into the songs of grief.

A man across the aisle from me wiped tears as he laughed uncontrollably at the students miming masturbation during the song “My Junk.” A gale of uproarious applause happened as the students bounced on chairs, ran up and down the aisles, and screamed the F-word with reckless abandon in the song “Totally Fucked.”

I thought back to my own high school theatre comrades, and our pre-show ritual in the dressing room: We’d huddle together and scream a chant with the F-word. It swallowed up the butterflies and created more space for exhilaration onstage. I can’t imagine the thrill these students felt unabashedly filling the whole theatre with the word. I wanted to jump into the conga line of students dancing down the aisle and sing along.

Later I locked eyes with Sheik and we shared a moment of disbelief at the encouraging laughter that greeted Hanschen’s same-sex kiss of Ernst, as a chorus of peers and parents whooped their delight and approval.

And then the roller coaster came to a screeching halt.

The heaves of laughter turned to audible sobs as the show went on. Kasky took the stage to sing “Those You’ve Known,” falling to his knees grieving the losses of his friend and his lover with the graveyard image projected behind him. The tears continued as the cast lined the stage to sing the final song, “The Song of Purple Summer,” all about moving forward past grief.

“When they came on and sang that the Earth will burgeon and bear, and that life will go forward and that the wounds of the spring are left behind in the purple of summer—it was stirring,” Sater said about this moment.

“I think there was something great about the audience laughing hysterically at ‘My Junk’ and really getting into ‘Totally Fucked,’” Sheik added. “Then you can sort of palpably feel the emotion in these other songs. It was cool to see the audience emotionally go on that journey in a rock club—that is an unusual experience. And that meant a lot to me.”

The audience spilled outside into a receiving line of hugs and high fives with the cast. The overall sentiment was relief, and for some teens in the audience, an exhilaration at what they just witnessed their friends do onstage.

Garrity’s father, Joseph, said he knew the content of the show going into rehearsals, but confessed that watching his daughter as Wendla onstage was a surprisingly difficult experience.

“It was really more emotional than I thought it would be,” Garrity said. “Plus we’ve been through a lot these past couple of months, which kind of makes it even a little more intense. But I think intense emotions are what helps people overcome bad times. I am hoping that the cast and the people who come to see it get the same thing I get from it—that cathartic feeling you get when you go through an emotional roller coaster like that. We’re a strong community and I think that going through this show is just another part of the healing process. I’ll remember this performance for a while.”

The students then funneled into a small rehearsal room for a talkback, creating a sweat box filled with sounds of elation and hunger pangs. Sheik and Sater sat at the front, ready to continue their conversation from the afternoon. I spotted the prop gun on a shelf just as one of the assistant directors swiftly covered it with a script. A film crew creating a documentary of the project adjusted cameras and boom mics above the 12 cast members, who were all entwined on the floor like a long daisy chain held together with love and support. The attention didn’t phase them. The room was filled with the comfort Sater spoke of earlier—the kind of collegial friendship that seems uniquely present among groups of theatre kids. The kind tight-knit club that everyone who wants to is invited to join.

The burning question for the authors, of course, was How’d we do?

“I feel that all that casts that have been part of a show remain part of a show, kind of remain part of the ghosts of the show in the way,” Sater replied. “This show is so much about kind of embracing your ghosts and going forward with your ghosts…My overall feeling was that everyone here did so much honor to this play, I mean the original play by Frank Wedekind, this incredible outcry against the hypocrisy and moral imbecility of adults,” said Sater.

“Don’t sugarcoat it, Steven!” Sheik said with a laugh.

“I was deeply moved by the event,” Sater continued.

“Leaving Spring Awakening apart from it, it means so much to me what Cameron and Sawyer and all of you guys have done to really move the needle on this issue,” said Sheik, addressing the big elephant in the small room. “You’re changing American history.”

“No pressure!” squeaked Kasky in a high-pitched voice, his head nestled against his castmate Kendal Simpson-Jones, who played all the mothers in the show.

The authors admitted that they rarely attend productions of Spring Awakening any more. “We really came to honor you guys and because, for us, you guys are a beacon of hope,” said Sater. “You really are giving us hope in a time that feels really dark. So we came.”

They also discussed the night’s most surprising audience reaction: the uproar around Ernst and Hanschen’s kiss.

“It was legitimately hilarious tonight in a way that I didn’t expect, and the audience was going nuts,” laughed Sheik.

“We’ve never done that scene with an audience before—I had no clue how they were going to react,” said Alex Wind, who played Hanschen.

“As your director, as your friend, and as your mentor, I think the two of you, no offense to anyone else, had the hardest job on that stage today,” said Barclay. “To hold the moment the way that the two of you did and commit to it—to not give into the laughter and screams from your friends.”

The cast’s youngest member, middle-schooler Eden Hetzroni, asked about her character, Krysta, a role from the show’s early concert version that was cut for the Broadway run and reinserted for this production. She noted that Lea Michele was helpful in shaping her approach to the role during rehearsals (this was Hetzroni’s first play).

“Did I do, like, justice to her?” she quietly asked.

Sater’s reply: “I think so, you brought the absent girl to life.”

The authors were also bemused by the cast’s interest in the background of their characters. “What do you think Melchior’s astrological sign is?” posed Kasky. The room erupted in laughter. “You guys are laughing about a question about my character!”

“Scorpio,” the authors responded in unison.

“I’m a Scorpio!” yelled Kasky excitedly.

The 40-minute conversation moved onto to cover the inspiration for the songs, the authors’ favorite moments, and NBC’s TV show “Rise,” in which a high school stages Spring Awakening. The talk could have gone on a few more hours, but it was a school night.

“I would like to, just as a parting word, just say I am incredibly impressed by all of you,” said Barclay. “I am moved, I am grateful, and I am quite honestly blown away that through it all…what you did tonight, that was very impressive. And we know that the odds were not necessarily in our favor this whole process. I love you all very much. Now hang up your costumes and go to school in the morning!”

I caught Garrity on her way out the door. We talked about applying for college theatre programs, about the importance of practicing self-care during shows, school finals, and, you know, changing the world.

“I’ve just been sleeping a lot, drinking a lot of water, and just being with my friends,” she said. “I think being with my friends is like one of the most important things that I have to do now. We’re all here for each other, we’re all leaning on each other for support, so it’s just so important that we’re together and stay together.”