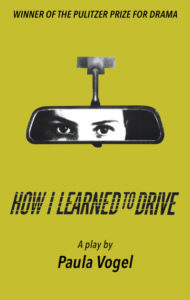

TCG Books will soon release the first stand-alone version of Paula Vogel's seminal 1997 play How I Learned to Drive (pre-order here) in which a young woman tells the story of being sexually assaulted by her uncle. The following is Vogel's new author's note for the publication.

We are in an interesting cultural moment in the United States as I write this; scandals about the abuse of power through sexual manipulation and assault proliferate in social media. A man with multiple accusers sits in the White House, while a man who was banned from an Alabama shopping mall for predatory behavior has run for the United States Senate. #Metoo ripples through our awareness, even as older women and men face the reality that their careers, their ambitions, and their visibility have already been impacted by that power for decades.

Mine certainly has been.

Do we come forward now, decades later, after our bodies, our lives, our relationships have been marked and changed by incidents long ago? Will it have impact for the young women and men, girls and boys, who endure abuses now?

I don’t know if I will ever again write a play that connects with such a wide demographic of audience members. For me, having been honored to witness How I Learned to Drive’s impact in 1997, I track the works of art that have since been produced and continue to call power out, be it Spotlight or The Keepers.

There have been friends who have told me that they could not come see my play in such an intimate public space as an Off-Broadway theatre. There was a woman who drove up from North Carolina when she knew I would be at a dinner in New York, just to hug me and thank me. A young girl in Los Angeles at a high school for LGBT students broke my heart when she worried that I might not accept her. A talented and lovely/beloved actress tried to work through whether or not she could direct the HBO movie as her first film and asked me: Is there a way to make this film safe? (I replied there was not. The film did not get made.)

Letters, emails, and post-play discussions in towns and universities made me aware of how deeply this experience runs, and that my play world is inadequate to capture it.

We may never know the statistics. We only know that once again we try to capture a cultural attention that quickly turns restlessly to the next crisis.

And although I have been told since 1997 that my play, written by a woman playwright, is not universal enough to receive a Broadway production, I have been given the gift of seeing How I Learned to Drive in Icelandic in a Broadway-sized house; I’ve watched the play in Mandarin in a small theatre in Beijing, and I have seen the play in Santiago, Chile, and Australia. It’s been done everywhere. Apparently the distance from the Vineyard Theatre on East 15th Street to the Market Theatre in Johannesburg or Croatia or Taiwan is not as far as the distance to Times Square.

And although I have been told since 1997 that my play, written by a woman playwright, is not universal enough to receive a Broadway production, I have been given the gift of seeing How I Learned to Drive in Icelandic in a Broadway-sized house; I’ve watched the play in Mandarin in a small theatre in Beijing, and I have seen the play in Santiago, Chile, and Australia. It’s been done everywhere. Apparently the distance from the Vineyard Theatre on East 15th Street to the Market Theatre in Johannesburg or Croatia or Taiwan is not as far as the distance to Times Square.

However, as I try to come to grips with the lack of control I have in terms of my own visibility and commercial success within the American theatre, I remain convinced that I have control in terms of how I see my identity.

How I Learned to Drive gave me that gift. It felt as if the play was rewriting me, and I will always remember the sensation of lightness I had in the middle of the night as I wrote it.

This is the gift of theatre and of writing: a transubstantiation of pain and secrecy into light, into community, into understanding if not acceptance.

The sensation of lightness continued thanks to my extraordinary collaborators who first presented the play. Thanks is an inadequate word to people who have changed me:

Doug Aibel, the artistic director of the Vineyard Theatre, who accepted the play before the first reading;

Mark Brokaw, one of the most extraordinary directors of our time, whose sensitivity and sense of tempo opened the play world;

Mary Louise Parker and David Morse, who were fearless in taking on these roles without denial or defense, and who together onstage urged each other to go deeper and deeper with every performance.

And my first Greek chorus: the magnificent Johanna Day as the female Greek chorus, the lyrical Kerry O’Malley as the teenage Greek chorus, and Michael Showalter as a ribald, adolescent male Greek chorus.

My thanks at this point would be longer than the play. To all the amazing actors who have taken on the play and who continue my sense of light, forgiveness, and acceptance, to all the directors, artists, crew, and most of all, to audiences who still believe that it is important to sit together in a darkened theatre to witness what continues to happen in our midst so that we may change it for the next generation:

I am grateful.

Paula Vogel

Wellfleet, Mass.

December 2017