What does it mean to be an American? When Actor’s Express artistic director Freddie Ashley and his team decided to stage both parts of Tony Kushner’s gay fantasia Angels in America, this was a question they felt was begging to be answered.

“America is a country that exists on a continent of unparalleled natural resources, but it was man-made,” Ashley told me. “We were a country that was a political construct. This is not a country that emerged out of a culture after thousands of years; this is a country that was made into being.”

The search for a national identity is America’s greatest source of pain and promise, and every time it seems an identity has been discovered, something comes along to disrupt that ideal. The transcendentalists thought they had the answers—until the Civil War broke out. The industrialists were determined to motorize America, and then the hippies came along and demanded a return to the earth.

When Angels in America was produced on Broadway in the early 1990s, it became another interruption to the American national identity. At a time when more Americans were accumulating wealth and education, Kushner saw America on the verge of a new millennium and asked, again: What does it mean to be an American now? And he ended up asking it of the most privileged of people: Broadway ticket buyers.

Some 25 years later, as Ashley writes in his director’s note for the new production (Jan. 12-Feb. 17) at Actor’s Express in Atlanta, “The millennium approached and the millennium arrived—and as the ghost of Ethel Rosenberg predicted, history did crack open.” And the question still remains: What does it mean to be an American, now that we’ve had a black president and gay people can get married, but no one can seem to agree whether black lives matter or whether a baker’s religious beliefs allow him to choose for whom he bakes a cake? More importantly, what do our different answers to those questions mean for our future?

“The last two years have awakened a lot of us to the reality that the ideals of the American experiment have not been fully realized in every corner of this country,” Ashley said. “When you have a country full of people who are starting to feel disenfranchised and are becoming aware of the disenfranchisement of others, and yet we live in this country that should be living up to an ideal—all of that’s present in the play. How does injustice reveal itself in a country that is supposed to be founded on justice?”

With these questions in mind, Ashley called on Martin Damien Wilkins to be his co-director. Wilkins had just directed Suzan-Lori Parks’s Father Comes Home From the Wars at the Express, and Ashley wanted to make sure that if the company was going to undertake this endeavor that the voices of artists of color were uplifted. Wilkins took primary responsibility for directing Part 1, Millennium Approaches, and Ashley took the helm of Part 2, Perestroika; they collaborated on the overall style of the production.

“I came to the play in high school because it was produced at Charlotte Rep, and there was a controversy that became national when they produced the show,” Wilkins said. “As a young man who at the time was coming out, I really responded to the journeys of Prior, Louis, Joe, and Belize. I had not encountered a character of color who identified as queer.”

That rare intersectionality also persists offstage, Wilkins pointed out. “It’s very easy for theatres to call and say, ‘Hey, you want to do A Raisin in the Sun or August Wilson?’ I’m passionate about the work of black dramatists, but to be able to work on Tony Kushner’s work, for Freddie to have called me—it was a wonderful way of diversifying my palette as an artist.”

Angels provides a rich palette of its own. The first play, set in 1985, introduces us to three different groups of characters affected by the HIV/AIDS epidemic and the politics of Reagan-era conservatism in different ways. Prior, a drag queen living in Brooklyn, reveals to his boyfriend Louis that he has AIDS. Harper, a Valium-addicted Mormon housewife, discovers that her aspiring politician husband Joe is gay. And powerful real-life New York attorney Roy Cohn, diagnosed with AIDS, is in denial after years of hiding his sexual relationships with men. There to help them to the other side are Prior’s friend, a gay black nurse named Belize, Joe’s mother Hannah, the ghost of the woman Cohn had executed, Ethel Rosenberg—and an Angel.

The second half takes all the characters deeper into their intertwined dilemmas: Roy discovers that no amount of money can cure his AIDS, Prior learns who his true friends are (and finds his true cosmic calling), and Harper and Joe and Louis try, falteringly, to live their truths. All must determine whether the lines they have drawn between themselves and others are worth keeping when an existential threat—to a marriage, to a career, to life itself—has crawled up next to them and claimed a spot in their bedrooms.

Actor’s Express is nestled in the King Plow Arts Center in Atlanta’s West Midtown neighborhood; as its name suggests, the building was a plow manufacturing company at the turn of the 20th century. Currently celebrating their 30th anniversary, they describe themselves at “Atlanta’s gutsiest and most vital theatre company.” Their completely flexible performance space seats about 200 people and occupies a corner in this mixed-use building.

But as cool as the space is, it presented some challenges for staging Kushner’s seven-hour epic. For starters, the small theatre doesn’t have a fly system for one of the show’s signature coups de theatre: the angel bursting through the ceiling at the end of Millennium Approaches.

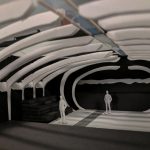

This is how Ashley, Wilkins, and set designer James Ogden came to take some inspiration from Kabuki theatre and New York City’s architectural landscape. Walking into the theatre, the audience is totally encapsulated by the set. Everything is black, white, and gray; it feels like being on the inside of a rib cage, with light boxes going down the middle of the ceiling serving as the spine. The skeletal effect was inspired by architect Santiago Calatrava, who has designed a number of iconic sculptures in New York, including the World Trade Center Transportation Hub and the “Shadow Machine” sculpture in the garden at the Museum of Modern Art.

“When you’re walking around in a city you see so often these lines running out beyond you, whether that be the sidewalk, the street, or bits of architecture,” Ogden said. “I wanted to give a hint of that through some of the coloration and lines without putting a sidewalk onstage. I wanted to do something I hadn’t seen before and really stretch the idea of what a performance of this play looks like.”

Upstage is an elevated platform with sliding doors beneath for set pieces to roll in and out. Since there are so many settings in the two plays, the designers of this Angels decided to use just a few pieces of furniture and minimal props onstage at all times for easy scene transitions. For the entrance of the angel, they made use of the platform, a white curtain, and some trippy lighting.

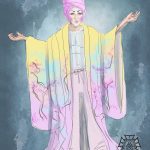

“A lot of productions tend to use certain iconography or collectively held images of what angels would look like, and we wanted to try something different,” Ashley explained. “That said, if we’re not going to have realistic scene locations, having more specific costumes helps to ground the storytelling for the audiences, particularly given that so many actors double and triple as other characters across gender lines.”

This is when the production called in costume designer Ivan Ingermann, who also teaches design in the University of Georgia’s department of theatre and film studies. Ashley met Ingermann when he directed a production of Cabaret at UGA last fall, and he knew he was right for the job.

“The ’80s are back,” Ingermann said. “You have a lot of interest in the ’80s in pop culture, with shows like ‘Stranger Things’ and Guardians of the Galaxy.” On the other hand, he said, “The core of this piece is the story—we didn’t want people to get tripped up on the hair, shoes, and clothes, because it would be laughable if I had done exactly 1985.”

Still, Ingermann, who lived in New York from 1992 to 2001, infused influences from the time period into the design of Angels. In the early ’90s, while he was getting his MFA at NYU, Kushner did a workshop production of Millennium Approaches at the school, and though Ingermann was not the designer on that show, he remembers it—and the world around it—very well.

“My memories of drag queens in the East Village are that at night they would be all pretty girl and during the day they would put on their boy drag,” he said. “Some would dress up and go to Wall Street. There’s a line where Prior talks about stealing Clinique, so that gave me a clue that he came from a different socioeconomic level. It’s kind of like squatter culture in New York, where these people fly to New York because they didn’t make it in their communities. Before the days of ‘Glee,’ ‘RuPaul’s Drag Race,’ and ‘Will & Grace,’ ‘gay’ was still a dirty word.”

Kushner depicts this shame poignantly through Harper and Joe’s relationship. Joe is in deep denial about his sexuality, and Harper is unable to trust her instincts that something in their relationship is not quite right, until the fateful argument when Harper asks Joe, “Are you a homo?” That question knocks the wind out of him and deflates their marriage. He tries to brush it off as her being high, but actress Cara Mantella, who plays Harper, pointed out that Harper’s hallucinations are her most clarifying moments.

“The moments when she’s speaking to these other ‘friends’ that may not be in real life, are her way of working things out for herself,” Mantella said. “On one level it’s her solving mysteries, getting support—she and Prior always seem to be revealing something to each other. The moments of hallucination and other realities to me are just her way of figuring things out for herself.”

This is where she and Prior meet, somewhere between reality and revelation. Grant Chapman, who plays Prior, said that what struck him most about this role is that Prior is so unapologetically gay. After his positive diagnosis, he questions why he is sick and alone, but never why he is gay.

“This role is like a Hamlet of the contemporary theatre—it requires all of your physical stamina and vocal range and variety,” Chapman said. “It’s still very rare for queer actors to be able to play a leading character in a play who is visibly queer and allowed to be complicated. A lot of my training as an actor was to not be too visible so that people know you have ‘range.’”

This very discussion came up in the rehearsal room: How effeminate should the characters be, especially in their interactions in the straight world? Trying to find the balance between how much “Yaaaasss girl” is too much and what honors the truth of the story was a challenge for both Chapman and Thandiwe DeShazor, who plays Belize. DeShazor said that while a flowing scarf helped him get at Belize’s essence, he recognized that the character is not a snapping queen when he doesn’t need to be.

“To get into Belize’s essence, I had to meditate, listen to some house music, and wear something totally different,” DeShazor said. “How do we get there without being a parody of a gay black man? You don’t want to give anybody a stereotype, because there’s not a character that’s been like him since then. The beauty of this character is that he’s very real.”

In 1985, the period in which the play is set, America was entering an era of excess: Glass ceilings were being cracked by affirmative action and Title IX, American pop culture exploded, a law was passed that would legalize guest workers but penalize employers who hired undocumented immigrants, and the uncontainable spread of HIV and AIDS created worldwide panic. In fact, in 1987, at a benefit dinner for the American Foundation for AIDS Research, Ronald Reagan recommended that states do routine testing for those desiring a marriage license.

Thirty-three years later, the specific ills and triumphs of that era have either dissipated or been elevated to the level of legend. But if you look closely enough, the ’80s are still very much with us: Affirmative action is challenged every time there is a change in the Supreme Court, women are still fighting for equal pay, and Congress is holding the fate of thousands of young immigrants hostage over a border wall.

“There are parts of the play that could read like we’re talking about right now,” Wilkins affirmed. “Roy Cohn was a huge influence on Donald Trump. Cohn advocates eviscerating people who defy him, and it gives a framework for how Donald Trump operates as a leader. We have leadership that grows not out of a sense of empathy toward others, but out of getting what you want at all costs.”

Then there’s the ever-present race issue. Rap music established itself as an essential American art form at the same time that the criminalization of crack cocaine left many children of color in impoverished single-parent homes. HIV and AIDS rates in the African-American community were dramatically higher than in other populations, in part due to transmission via dirty needles. As the saying goes: When white folks catch a cough, black folks catch pneumonia.

Though he doesn’t have HIV/AIDS, the character of Belize is Kushner’s attempt to address the intersectionality of race and sexual orientation in that fraught time.

“Belize is the moral compass of the show in a lot of ways,” said DeShazor. “While he’s watching all of this go on, he’s thinking, ‘Y’all have no idea. You’ve never seen oppression…’ Belize is a caregiver; he is a nurse, and he keeps Prior together.”

At Actor’s Express, Belize wasn’t the only face of color: Ashley and Wilkins cast Parris Sarter, an African-American woman, in the role of the Angel, to emphasize, as DeShazor put it, “the role black people have played in our society. We take care of y’all.”

Actor’s Express is only the second theatre in Metro Atlanta to produce “Angels in America” since it opened on Broadway 25 years ago. The Alliance Theatre produced both parts in 1995 under the direction of then-artistic director Kenny Leon.

To stage this play then was revolutionary, but it can still feel that way here: Just last fall Georgia state representative Dr. Betty Price suggested a quarantine to address the state’s resurgent HIV/AIDS epidemic. Price, the wife of former Congressman Tom Price, who briefly served as Trump’s secretary of health and human services before resigning in September 2017, said in a public hearing: “It just seems to me it’s almost frightening the number of people who are living that are potentially carriers—well, they are carriers—but, potential to spread. Whereas, in the past, they died more readily, and then at that point, they are not posing a risk.”

In the 35 years since the AIDS epidemic wreaked havoc on communities all across the country, advancements in medicine have taken away the kiss of death that once characterized the syndrome. Infection rates are down overall across the country, but they are disproportionately high in the South, which accounted for half of all new HIV/AIDS diagnoses in 2016, as well as among African-American and Latino men. According to a 2016 report by the Centers for Disease Control, Georgia has one of the highest HIV/AIDS infection rates in the country—26.3 per 100,000 people, second only to Washington, D.C.

Carolyn Cook, who plays Hannah Pitt and Ethel Rosenberg, remembers the outbreak of HIV and AIDS in the ’80s well, and the toll it took on the theatre community. Cook is a heavy hitter in the Atlanta theatre community, and her stirring performances continually cement that position. The scenes between her and Robert Bryan Davis, who played Roy Cohn, are theatrical perfection, like watching Ali and Frazier spar—a dance of power and prowess.

“I remember as a child really believing that we were in a new scientific age, and that we had vaccines for everything,” Cook said. “The generation before me had polio, but I had a polio vaccine. I remember when I was about 12 or 13 believing that by the time I grew up there wasn’t going to be any more disease. And then there was AIDS. It was like a slap in the face…It was scary. You would have your address book and start marking people out.”

For the production Actor’s Express has hired a community engagement consultant and is hosting a number of programs to further educate the community about what HIV and AIDS look like now. Every Saturday audiences are able to participate in a “Chat & Chew” where they see Part 1, have a dinner and discussion at a local restaurant, then see Part 2. Before every Thursday night performance, community organizations that support the LGBTQIA community and that provide services for those with HIV and AIDS have tabling space in the lobby area.

But for all of the sociopolitical and even medical relevance, the space where Angels in America resonates most strongly is the hardest to pinpoint: the spirit. When the mind goes crazy, the heart breaks, and the organs shut down, it’s the part of us that remains felt and not seen. The spirit is indestructible. In Kushner’s essay “Notes Toward a Theatre of the Fabulous,” from John Clum’s book Staging Gay Lives, he writes: “The Fabulous is the assertively Camp camp, the rapturous embrace of difference, the discovering of self not in that which has rejected you but in that which makes you unlike, and disliked, and Other.” Fabulous, thus defined, is not an outfit, religion, or economic class. It is the power that comes with self-knowledge, which is ultimately what the characters have to find in the play.

“We have God inside of us, and we have the possibility to be angels to other people,” DeShazor said. “The more we are willing to tear down barriers, relate to each other, listen, and educate ourselves, the more we get into a space where we can be more God-like, or angelic. It’s more than charity. It’s being able to be that person who someone can call on in the middle of the night. We all have the capacity to be angels—we just have to know that we’re worth it, that we matter.”

As the third decade of the 21st century approaches and America continues its painful quest for a national identity, a new question arises: Will we be angels to each other? It is possible to want, and to fight for, the best interests of someone with whom you have nothing in common. The only context for humanistic value is humanity. Separation has shown us clearly what it yields; perhaps it is time to give togetherness a chance.

Kelundra Smith is an arts journalist based in Atlanta.