I felt my body tense up. A black man—rather, a mannequin of a black man—lay headless, forgotten, on the side of the stage. I wanted to leave the theatre, but as a critic I couldn’t. The show wasn’t over yet.

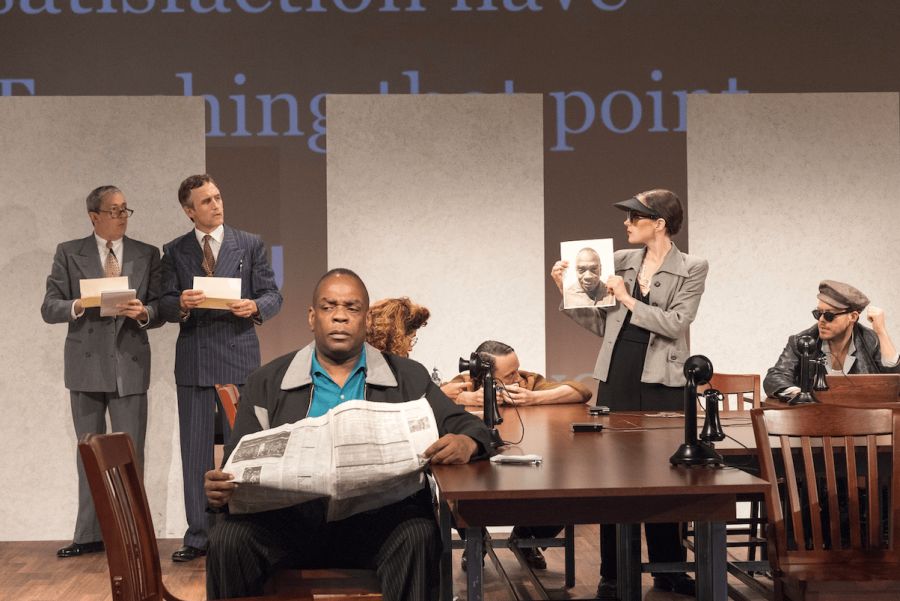

Last month Elevator Repair Service premiered its adaptation of Measure for Measure at the Public Theater. Though the production would have otherwise been an inventive but harmlessly flawed take on one of Shakespeare’s notorious “problem plays,” whatever interesting or innovative elements the show introduced were quickly overshadowed by what struck me as its racial insensitivity.

In this production, Claudio, the poor prisoner at the heart of the play whose transgression (extramarital sex) sets the plot in motion, was played by one of only two black actors in the cast, Greig Sargeant, with the other, April Matthis, taking the role of Mariana, the jilted, shamed woman who must marry to be redeemed in good society. So we had a black Jezebel and a black “criminal” unjustly imprisoned by a corrupt authority figure, played by a white actor, for impregnating a woman played by a white actress. The scenes between Claudio and his sister, Isabella, who may save him by giving up her virginity, become that of a black man begging a white woman for help, though ultimately she’s unwilling to sacrifice her dignity to do so.

But it was not until about three-quarters through the production that the great switch took place—the maneuver by which Claudio, who is slated for death and decapitation, is swapped out for another, already deceased prisoner, his head presented as proof of the deed. Even if we left aside the problematic notion that this black Claudio could so easily be swapped out for another imprisoned black man, there was no way to dismiss the scene in which Claudio’s dead doppelganger was brought onstage in the form of a life-sized mannequin, cartoonishly decapitated, with the body thrown to the side. It was a scene played for laughs, but the black body remained on the side of the stage for the rest of the production, and the play continued as though it wasn’t even there.

As I watched I was suddenly aware of all the bodies in the room; I was one of less than a handful of people of color there. I spotted only one other black person, a few rows down. I couldn’t see any part of their face, much less their reaction—but surely they were as aghast as me? Surely they weren’t laughing either?

When I returned home that night, I was certain I would find that my fellow critics had already commented on the racial implications of the production; after all, art doesn’t exist in a vacuum, and critics above all have a duty to contextualize what we see, to relate what’s happening onstage to what’s happening offstage, in our country, in our world right now. In the case of a character who happens to be played by a black man, and who is set upon by authorities who happen to be played by white actors, the ways in which those kinds of casting and directing decisions—intentional or unintentional—reflect the times in which we live are clear. These are the kinds of things critics cannot overlook. When a black body is literally used as a prop on a stage, what is there to miss?

But of the more than 20 newspapers, magazines, websites, and blogs that ran reviews of this staging of Measure for Measure, not one mentioned the casting or the implications it had for our current cultural context. Reviews ranged from “remarkable,” “hilarious,” and “wildly inventive” to “gimmicky,” “infuriating,” and “inscrutable.” But only one mentioned the mannequin scene at all, with the only critique of it being the tonal shift, as the writer noted that the laughs were “tempered somewhat” by the scene.

How could I, as a black theatre critic, as a young black woman, interpret this oversight? It’s a problem larger than the missteps of any one production, but rather one that can be laid at the lack of diversity in the field of theatre criticism. In an already small world in which full-time theatre critics are few and far between, it’s hard not to notice that the landscape is blindingly white.

Of the 10 largest U.S. newspapers by circulation, none of the title-bearing theatre critics are people of color. It’s a small sample size, to be sure, but reflects a broader trend. According to a June 2017 diversity study released by the Actors’ Equity Association on hiring in Broadway, production tours and Off-Broadway productions in 2013–2015, white actors took the majority of all onstage contracts by more than half and were generally hired with higher salaries. And according to Broadway League’s Demographics of the Broadway Audience 2015–2016 study, 77 percent of all tickets purchased to Broadway shows in that period were purchased by white audience members.

In other words: It’s an art form dominated by white faces writing about white faces performing onstage to predominantly white faces.

When theatre, like any number of other art forms, is dismissed by detractors and cynics as inaccessible and irrelevant, part of that question of accessibility and relevance simply has to do with the kinds of voices that are missing from the industry and in its coverage. Inaccessibility is a product of limited perspective, irrelevance a product of ignorance and disengagement from the world in which we live.

There’s a partnership of sorts between the critic and the art form, as contentious as that relationship may seem at times. The art is created and the critic chews it over, breaks it open, revealing it to readers and audience members, and, hopefully, the makers and performers themselves. The critic brings perspective, and perspectives—particularly differing perspectives—are what can help the art form grow.

In a New Yorker article published earlier this year, music critic Alex Ross defended the role of arts critics in our digital age: “They can open new worlds in the minds of readers; a passing phrase may spur a lifelong love.” But certainly there is a limit to the new worlds a writer may introduce to a reader in line with the limits of the writer’s own experience. In an ideal world, a critic can transcend that, subordinating himself or herself to the art, opening him/herself to the production in front of them. But in reality, every writer has his or her blind spots. And when the critical voices gathered to write about an art form all share the same ticked-off demographic boxes, those blind spots can become a collective ailment in the field.

In 2016’s The Critics Say: 57 Theater Reviewers in New York and Beyond Discuss Their Craft and Its Future, former Newsday theatre critic Linda Winer says, “The fact that there’s only one African-American theatre critic—Hilton Als at the New Yorker—matters. There are no Asians. There are no Hispanics. There’s a greater variety of perception when you have different kinds of people looking at things.” In the same book, New Yorker contributor Michael Schulman laments that his colleague, Als, was the only one critic he saw questioning the representation of black characters in a revival of Hair, saying, “He’s the one who would notice that kind of unconscious, institutionalized racism in a musical.”

The lack of diversity in theatre criticism not only does a disservice to the field and the readers, but also to the playwrights and productions. Certainly such artists as Suzan-Lori Parks and Ayad Akhtar, and others artists of color whose work speaks particularly to questions of identity, deserve to have their work scrutinized by a more diverse group of critics. In the age of Hamilton fanatics in New York, Chicago, London, and beyond, audiences have proven that there is not just space but a hunger for stories by and about people of color that work to rewrite, expand, or totally replace the white canon. So where are their peers in criticism? Whatever degree of visibility some artists of color in the industry may attain doesn’t make up for the fact that the racial status quo of criticism remains.

Of course, this isn’t to say that a writer of color has the responsibility to speak to any and all matters of race as they’re presented onstage. This is a kind of tokenism people of color, especially writers of color, are familiar with on a daily basis. Too many times have I felt an obligation, as the black person at hand, to address the elephant in the room, whatever color it might be, and open myself to the possibility of derisive commentary on my own critique: Am I being too sensitive about the topic? Am I not fully considering the author’s or the production’s intent? Am I missing the point completely? I don’t want to be a representative of my race or the spokesperson for racial sensitivity in theatre. But I do need to feel that my voice, my perspective, my experiences—or something close to them—are represented in some form on the page or computer screen.

The world of theatre criticism is a white pantheon wherein the same voices reign for years, dominating the discussion, while editors wonder why that discussion may have grown stale.

Diversifying those ranks is an easy answer—perhaps too easy, you might say. With such heavy hitters as the New York Post, Daily News, and USA Today having eliminated their full-time theatre critic positions in the last few years, and with arts sections being downsized, the problem is larger than just whose names are on the mastheads. In a January 2017 article for the Columbia Journalism Review, arts critic Jed Gottlieb reported American Theatre Critics Association Chair Bill Hirschman’s take on how times have changed in the world of criticism: “Hirschman said twentysome years ago there were easily a hundred staff theatre critics at papers. Now he ‘can count on his fingers’ the number of full-timers out of the American Theatre Critics Association’s 220 members.”

Across the country, newspapers, magazines, and websites are trying to figure out how to serve readerships with different ways of consuming media in an age that values hot news, trends, and voices more representative of the audiences they serve. For readers, the old standards no longer measure up. Shouldn’t it be the same for the writers as well?