A couple of years ago I was at the International Theatre Engineering and Architecture Conference in London, a meeting that draws a group of 200-300 people from around the world who make their living conceiving, designing, building, equipping, renovating, using, fighting, filling, and managing theatre spaces. An intriguing thing happened there: One guest speaker after another questioned the need for any more theatres to be built—ever.

Not everyone took that position, of course, but those who did included an iconoclastic facility administrator or two, several artistic directors, and an articulate and talented set and costume designer named Lucy Osborne. Osborne asserted that many in her generation were less interested in working in theatres than in simply finding a space—a room, a whole floor, a whole building—to occupy in a particular way that creates a vivid experience. She didn’t want to be told how to use a space or have any fixed seating to deal with. She spoke about her interest in experiences rather than narrative-based works.

Another participant suggested that writers and directors will in short order no longer hold their centuries-old monopoly on the creation of theatrical events, and that now works can finally be conceived and devised by designers, by performers, or by technologists, leading to new forms of expression and experience. (Of course, 400 years ago the proscenium theatre was a theatre form devised by scenic designers and technologists, not monopoly-seeking writers or directors. Oh, well.)

One presenter talked about how technical and creative innovation in live performance is now being led by the world of rock ’n’ roll touring and spectacles like the Olympic ceremonies, because, frankly, that’s where the money to pay for innovation is now—much like the money provided by princely patrons during the Renaissance. This, I thought, sounds familiar.

Over the last century we’ve seen Western theatre expand its palette of standardized performance spaces to include a number of alternative forms: Thrust, arena, end-stage, and flexible spaces of all sorts have been added to the proscenium form that has prevailed for roughly 350 years. Recent decades have seen a growing interest in found spaces, both for ongoing use as alternatives to purpose-built conventional venues (the Park Avenue Armory in New York City, for example), and as one-off containers for temporary performance-specific occupation (like the Chelsea commercial building transformed into the “McKittrick Hotel” for Punchdrunk’s immersive hit Sleep No More).

This tendency to accrete rather than to replace may be a peculiarly modern phenomenon. In the past, when empires fell, they really fell; they crumbled to dust or were buried by natural processes or subsequent civilizations. Perhaps it’s too soon to tell, but today the past seems to live on all around us—in the built environment, in the enormous range of new and old forms of artistic expression available to us, through purposeful conservation efforts and scholarship, on Netflix and YouTube, and on the internet, where things never really disappear.

What at first looks like evolution—from campfires to hillsides to amphitheatres to courtyards to playhouses and onward into the future—is really the recapitulation of another kind of trajectory, from improvisation to formalization. As each new theatrical practice is improvised by a new culture or by restless, visionary (or hungry) artists using the materials at hand, its successes are repeated; standardized practices emerge, traditions and expectations are established.

Invention begins with the simplest materials, ones close at hand. The Greeks didn’t start out by building stone amphitheatres. They looked around at the sky, the processional paths, the altars, temples, threshing circles, and hillsides of their towns and cities, and they improvised. They made choices about how best to employ the places and things around them to create the communal experience they were striving for. They used found features.

Over time, the found spaces on these hillsides were enlarged, improved, modified, and set in stone—literally. They were no longer found spaces, really, but in a sense idealized imitations of found spaces, preserving the basic features of the originals. In so doing, the Greeks codified a new building type, which we recognize as the Greek amphitheatre.

The Romans were more advanced engineers; they didn’t need a hillside to make an amphitheatre. They made buildings that were idealized versions of the earlier Greek model, intentionally manufacturing places of cultural significance in the new cities they established throughout their empire. They standardized and homogenized the building type, but in reality these were purpose-built imitations of imitations of found spaces.

The same cycle can be seen later in England: An improvised performance on a wagon in a marketplace becomes a temporary trestle stage in a borrowed inn courtyard. With each successive effort the model is further refined, until someone gets the idea to make a purpose-made building along the same lines—and the Theatre in Shoreditch, just outside London (now part of the city’s East End), is born in 1576. This purpose-built, idealized imitation of a once-improvised arrangement was then itself imitated: 11 more courtyard playhouses were built along these lines in London over the next 47 years before political events brought that great, fertile period to a close.

Renaissance party planners, in an effort to glorify their princely patrons by outdoing the rival houses, created spectacular entertainments in temporary custom-built installations in courtyards and palace halls to celebrate important weddings, state visits, and political alliances. Brilliant painters and designers devised these installations, together with poets and musicians who wove together music, dancing, breathtaking scene changes, costumes, special effects, and astonishing tricks. The flow of princely money permitted enormous innovation, and soon led to specialized buildings to accommodate these activities. A new building type was born—the proscenium theatre—along with the forms opera and ballet.

These forms’ early improvisations in found spaces were soon codified, idealized, refined, disseminated, repeated, and immortalized. The cycle of found-space to imitation-found-space to standardized-form-of-imitation-found-space played out once again.

If we step back and squint, it begins to seem that all of this is really a steady oscillation between found and designed. When the pendulum swings too far in the direction of a formal tradition and the scope for invention and exploration feels too constrained, artists will seek to break the creative logjam and develop alternative means of expression. This process strikes me a little like the creation of pearls: Perhaps an irritating grain of sand that lodged by chance in an oyster’s shell is the initial inspiration. That accidental core is eventually covered by an accretion of layer upon layer of abstraction and standardization, smoothing out the rough edges and ultimately producing objects that are valued because they are perfect, homogeneous, featureless, and identical to each other. Predictable. Regular.

And crying out for further artistic transgression! By the mid-20th century, frustration with the proscenium form led to experiments with arenas, thrusts, and flexible studio spaces. These experiments, too, were soon standardized, formalized, copied, and ossified in their turn, setting the stage for the next round of exploration—the shift from purpose-built theatres to found spaces (with their ready-made emotional qualities and symbolism), and now, again, to carefully contrived scenographic environments in which the emotional content is designed rather than found. (I say “again” because Jerzy Grotowski and others were doing this in the 1960s. There are many pendulums around the world today, swinging faster and faster, and not necessarily in sync with one another.)

As a theatre form becomes standardized, questions of theatre architecture shift focus from the fundamental problem of how to employ space to create meaning and shared experience (driven by theatre artists), to important but less fundamentally innovative questions of refinement and incremental improvements in scale, capability, quality, safety, commercial performance, and technology (driven by architects and related professionals). The work onstage may also shift focus, with authors, composers, directors, producers, and other devisers of work no longer inventing entirely new practices but adopting and refining traditional patterns within traditional structures: the two-act play, the 11 o’clock number, the overture. The work becomes less about the invention of a new system of expression; instead, like the buildings themselves, it starts with the premise of an accepted form, then seeks richness and invention within that form by building on or playing against its conventions.

Context is an important tool for theatre artists, and just as an ancient Greek amphitheatre drew power from an adjacent altar or temple, our theatres carry specific meanings that can be used. As theatre forms and theatre buildings age, their meaning to contemporary populations changes. Their new connotations may, for a time, fall out of sync with the era and the artists creating new work. Like fashion or fondue, as a theatre ages it may represent in turn what is novel, normal, passé, dowdy, depressing, forgotten, curious, intriguing, and novel all over again. (Consider the Harvey Theater at Brooklyn Academy of Music, for example—so old it’s new.) With these shifts, a theatre’s utility to an artist evolves like language; new spaces, like new words, need to be coined to express new ideas (or old ideas in new ways)—the old ones carry too much baggage with them.

Old forms, too, become enmeshed in the economic systems for which they were created. When times change, and the financial models and even the neighborhoods evolve, some theatres will be left without a useful purpose, like the hundreds of vaudeville houses and movie palaces all across the U.S. that so many hopeful and committed preservationists want to renovate and reopen in spite of their general lack of utility.

Today we’re seeing the cycle repeat once more. Many artists seem uninterested in any space that has been purpose-built or tailored for performance, preferring to find new spaces to occupy for each new work. This is happening in various ways and at several scales. Punchdrunk’s Sleep No More, which operates in a series of meticulously art-directed environments in dozens of relatively small rooms within an existing commercial building, is but one example of this trend. At the other end of the spectrum, the Park Avenue Armory—part of a network of international spaces like Germany’s –Jahrhunderthalle in Bochum and the Salzlager in Essen, which support art on an industrial scale—is an example of a vast found space that inspires visual and performance artists to create and present work in new ways, most recently a grand-scale incarnation of Eugene O’Neill’s The Hairy Ape.

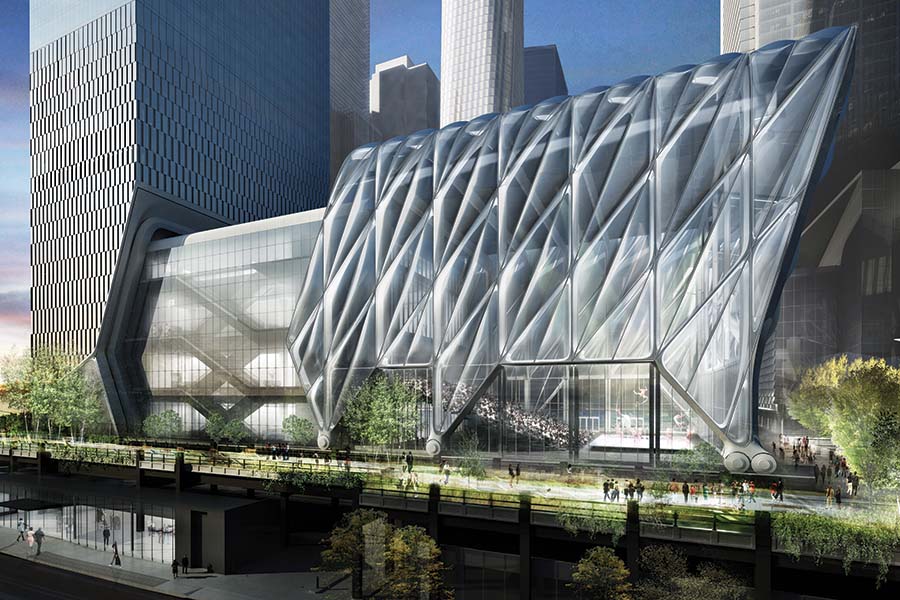

But there’s already evidence, in spite of the screaming contradiction of it, that this movement away from purpose-built performance spaces will soon itself be codified (and perhaps co-opted) into a standardized typology and repeated around the world. Prospective clients have already asked my theatre planning and design firm to help design spaces to be purpose-built for the kind of work Punchdrunk makes. Others have asked for new-built Armory-style places: purpose-made found spaces, essentially, extraordinary but non-deterministic, in which to make “big” art and performance.

One such space, the Shed, has been planned and is under construction within a commercial development on Manhattan’s West Side. There is at once an earnest belief in the future of the new and, it seems, an interest in repeating the apparent success of landmark productions in improvised spaces. But there’s nothing surprising about this: It describes the motivation for building the Theatre, the Globe, and the Rose in the 1580s and ’90s.

There’s a joy in making something new, stepping into the unknown, overcoming great obstacles. There’s also pleasure in taking an idea to its logical conclusion and doing it better than it’s ever been done before. Sometimes when things are too easy for us, we seek complications and constraints. It’s the struggle that keeps things interesting. At one extreme is the impulse to be nimble, to improvise, occupy, and adapt; at the other the desire to formalize, perfect, institutionalize, perhaps commercialize, and propagate. Back and forth over the centuries the pendulum swings between rejecting and embracing inherited practice and the standardized approaches of the day. The cycle continues over and over.

Something quite beautiful was said at that conference in London, which somehow captures this impulse perfectly. A theatre consultant from Holland noted that his country has the highest number of lavishly equipped proscenium theatres per capita anywhere in the world, with motorized, computer-controlled rigging mandated by law and installed in every venue. But a theatre student came to him recently and said, “You’ve given us hundreds of spaces in which everything is possible and nothing is allowed, but what we want are spaces where nothing is possible and everything is allowed.”

There you have it: the human condition in a nutshell.