Across the top of a rough-hewn painting depicting the Earth with upside-down houses and skyscrapers plummeting from its surface appeared the following words: “One day this world will fall…” That proclamation came at least partly true when the world encompassing that artwork, indeed the entire building on whose wall it was scrawled, saw its demise in May with the closure of the Off Center, the longtime home of Austin-based collective Rude Mechs. Since their lease was not renewed, the property is now owned by their next-door neighbor, the University of Texas Elementary School, which may repurpose the building or knock it down.

While other stories in this issue explore buildings going up around the U.S., the Rudes’ departure is a symptom of a larger housing crisis facing Austin theatre companies, including Salvage Vanguard Theater, which performed at the Off Center before getting their own building in 2006—then returned to the Off Center this past season after losing their space.

With the swing of the figurative wrecking ball looming over it, the Off Center—which the Rudes had overseen since 1999—hosted the creation of one last new piece by the group, Not Every Mountain, which ran in early workshop form at the Off Center March 30-April 9. Make no mistake: Even without their home base, the troupe has no plans to stop any time soon. In fact, the drive to continue was woven into the new play, the company’s 26th original work since Rude Mechs—short for Rude Mechanicals, the beleaguered amateur actors of A Midsummer Night’s Dream—began in 1995.

Not Every Mountain is part of a larger project-in-progress called Perverse Results, whose name derives from a corollary of Murphy’s law, illustrated by examples like Barbra Streisand’s attempt to remove from the internet a photo of her home leading to wider circulation of it. The plan is to create a variety of shows, then collate pieces of them into a single work, Perverse Results, though the individual plays might stand alone as well. The final product might be something scale-able and modular, which would afford greater flexibility when the company tours to theatres of varying needs and resources. This different method of working—which itself stems from the concept of unintended consequences—is an exploded version of the Rudes’ typical approach, in which the troupe builds a play together by creating more material than can fit in a single evening, then whittles that down to a manageable length.

The idea to have the five co-producing artistic directors (or COPADs) generate separate shows was solidified in mid-October 2016 in true Austin fashion: over chips and queso on the roadside patio of El Chile Cafe y Cantina, a Tex-Mex restaurant on the city’s east side, a quick drive from the Off Center. COPAD Thomas Graves, who got to know every nook and cranny of the Off Center as its venue manager and who would be a driving force behind Not Every Mountain, explained the premise at that lunch.

“What if we each explore whatever we’re interested in,” he said, “in our own way, and come into the room more prepared and be like, ‘This is the thing that I’ve been exploring’?” COPAD Shawn Sides furthered the thought: “In a way this workshop is not even the first workshop. This workshop is like a COPAD retreat,” she said, referring to the periodic getaways the Rudes take to explore their art.

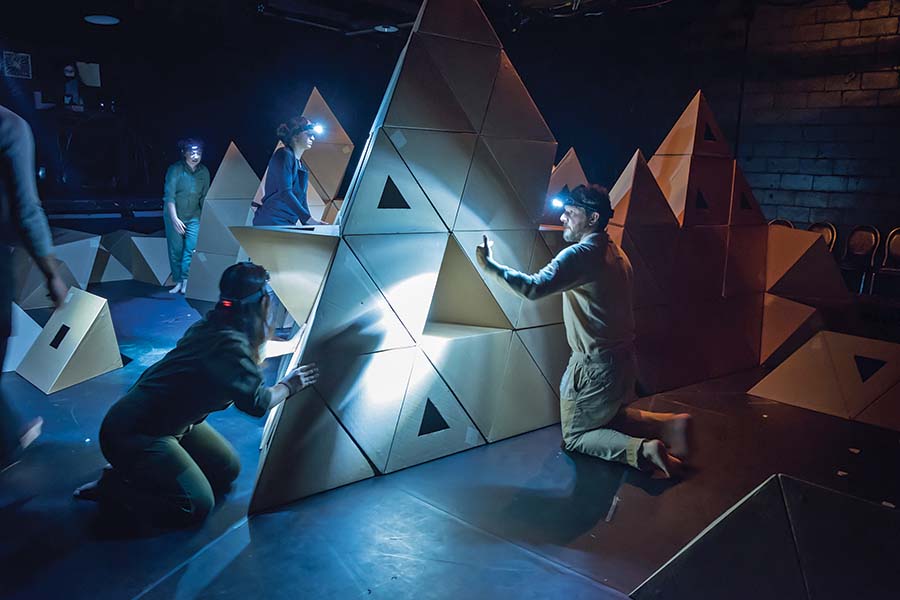

Over the next few months the Rudes started developing pieces, including the one that would become Not Every Mountain. Graves’s plan was to create a dance work inspired by mountains, playing with the idea of cardboard triangles that would connect to each other with the aid of magnets to make various geometric shapes, which would then form a mountain and would also collapse easily.

In January COPAD Kirk Lynn, the company’s chief writer, noted that Graves’s idea tapped into their longstanding desire to make a piece that “addresses our admiration for the natural world,” countering the tendency of most plays to take place indoors and over the course of a relatively short time span. “So Thomas really wanted to think about these eons, and he liked the idea of building a mountain and then letting centuries pass. And, like, giving it weather and having birds and clouds come.”

When Graves initially presented his mountain concept, Lynn was working on his own project, a piece employing cassette players to lead an audience to create a play. But coincidentally he also had mountains on the brain: As a morning warm-up exercise Lynn had been drafting a poem, about 40 pages of raw text, with a series of lines starting, “Not every mountain…” Without hesitating, Graves and Lynn decided to combine their efforts into the single project that would become the first episode of Perverse Results.

So they set to work: Between the October meeting and mid-January, Graves consulted books about mountains and spoke with a geologist, and Lynn and Graves held about a dozen two-person “pretending” sessions. In those sessions Lynn sat and read the text while Graves acted as the remainder of the cast, building mountains with the cardboard shapes he had on hand and miming the rest. When it came time to bring in the other performers, Lynn and Graves first looked to dancers from a physical theatre performance they’d seen in Austin in January, Loose Gravel, by Frank Wo/Men Collective.

Frank Wo/Men artistic director Kelsey Oliver, who appeared in Loose Gravel, would end up in Not Every Mountain, joined by Graves and Lynn, plus others from the local community: Pete Dahlberg, Eva Claycomb, Kevin Jacaman, Derek Kolluri, Rude Mechs managing director Alexandra Bassiakou Shaw, and Panda Landa. Graves also served as director and scenic designer, with Dahlberg working on design and technical direction and Kolluri handling props. (Others in the mix: composer/sound designer Peter Stopschinski, costume designer Aaron Flynn, lighting designer Brian H Scott, and stage manager Jasmine Kurys.)

The Not Every Mountain company first came together on Feb. 10 for a 9 a.m. rehearsal, the first of many mornings at the Off Center. Fueled by coffee and breakfast tacos, the group gathered in the Off Shoot, the Rudes’ main rehearsal space. The creative team, led by Graves, walked the performers through their concepts for the workshop, first showing the various playing areas on a large set model, raised off the floor in the center of the studio. Early in the session, Lynn commented that they should enlist the help of Deborah Hay, the experimental choreographer who collaborated with Rude Mechs on Match-Play. This was more than a passing reference: Lynn cited Hay multiple times throughout the preparation process for Not Every Mountain.

Later in the session Graves demonstrated an apparatus for lifting flat sheets of cardboard off the ground to become mountains, and a few people walked through the hollow center. Though some of the performers were meeting for the first time, there was a palpable sense of playfulness and camaraderie from the start.

The bulk of the morning was dedicated to a read-through of the piece, with Lynn in the far corner of the room sitting with a script and reciting the text and everyone else seated around him, some on chairs and others on the floor, story time-style. Graves sat against a stack of cardboard, at first staring forward, pensively pulling at strands of his beard, then getting up to act out movements—mountain-building, birds flying overhead—while the rest of the cast watched the two of them in rapt attention.

What took place that day was a fair representation of what the piece would become: a serious yet whimsical series of episodes involving the group simulating weather and seasons, working together to put up and take down mountains, and inviting audience members to help bring them alive. (Programs would be printed as single square sheets that attendees could fold up to make mountains of their own.) This would all take place against the backdrop of Lynn’s soft-spoken rumination on life, relationships, and ephemerality. An audience member could focus on one area or another, or just take it all in. Taken together, these elements produced a meditative, soothing effect—with plenty of laughs along the way.

As rehearsals progressed, the company developed segments of mountain-building as well as representations of natural elements, such as a rain storm in which Kolluri sent bursts of mist into the atmosphere with a garden sprayer and Oliver embodied lightning through quick, dance-like movements with a rope light. In the process of developing the mountain-building sequences and grappling with issues of polarity as they learned how to attach the cardboard shapes, they created their own language. Rules or best practices became “razors,” so called because when Kevin Jacaman suggested that only one shape would point directly up at any time, and all others would be placed at angles, the rule was named “Jacaman’s Razor,” after Occam’s razor. Another example: One system for storing materials was called the “probanus,” a portmanteau of “probe” and “anus” considered preferable to the gender-binary talk of “male” and “female” ends when referring to the pointed stack of mountain parts.

Dahlberg, a carpenter and furniture-maker by trade who has known Graves for a while but had never had a chance to work with Rude Mechs, happily oversaw the show’s technical realization. In the first week of March the Rudes held a series of factory sessions in which the cast and other members of the community built the magnetized cardboard components: hundreds of penta- and tetrahedrons, which the performers would use to construct mountains each night. Dahlberg recounted how, once everyone had gotten warmed up and had had a couple of beers, the team could complete two units every 70 seconds.

For the stage, they went with an arena configuration, with the stage management and sound booth at one long end and Lynn as the Reader and Dahlberg—running the Pantomelter, a mechanism for creating wax stalactites—on the other, placed among the audience on risers. (Dahlberg recalled telling Graves in an early planning session, referring to the Pantomelter, “We’re going to build this crazy contraption, and I want to be in the show as the guy operating it.”) Because the mountains would obscure some areas of the playing space, theatregoers would have wholly different experiences depending on where they sat. “A mountain basically defines societies; it separates one from another,” Dahlberg noted. “We wanted to do that with different sides of the audience.”

Lynn himself got to observe the show from those different perspectives, not only because he sat up above and could view all parts of the playing area but also because he and Graves enlisted Jennifer Kidwell to play the Reader in the second weekend. Kidwell, a company member of Philadelphia’s Pig Iron Theatre Company, had collaborated with Graves at Pig Iron and elsewhere; her attendance of the show during its initial week marked her first time in Texas. A seasoned actor, she took a more performative approach than Lynn.

“It is so well constructed in its ability to be flexible,” she said, referring to the openness of the text. “I think the latitude you can have with that component of the performance is what makes it so strong.” After the run, Graves commented how much he appreciated having Kidwell’s voice in the mix in addition to Lynn’s. “I’m really happy that we did both, and I think we’ll keep doing this,” he said. “Also it’s important in terms of having different bodies onstage. Even those words coming from a queer black woman, those sentences take on different meanings.”

Rude Mechs performances usually have an element of striving to make people feel included, of bringing people together—often literally. This run of Not Every Mountain was no exception, with audience-participation moments like the one in which people in the first row were handed plastic miniature animals and encouraged to place them on the mountainside. As attendees entered the space each night, the action was already happening around them, with the “Planes on Strings” sequence of several hills being raised from flat planks of cardboard. (Though originally that section was part of the main performance, it was moved to the preshow when the first run-through clocked in at about twice the desired length. “I was devastated,” Graves confessed about the cuts they needed to make, saying the situation momentarily made him feel like he was “never going to do theatre again.”)

The most notable element of audience interaction took place at the top of the official performance with a paean to the room and to the shared experience of being there together, an invocation Graves improvised each night. In early discussions other COPADs expressed concern that such a prayer would be overly serious, but despite the solemn impulse behind it—an homage to the Off Center—the tone was light. In January Lynn commented that any such earnestness would be offset by elements such as his crown, which he envisioned as half Sun Ra (the jazz giant) and half Sark (a villain from the movie Tron). “If we’re gonna be holy,” Lynn said, “we’ll be holy fools, not holy priests or something.”

In an increasingly high-pitched drone that quickly turned into falsetto, on the final night Graves performed a particularly emphatic rendition of the hymn. He intoned a series of rhetorical questions first as call-and-response and then solo: “How did we get to be heeeeeeere?…How did it happen, for millions and millions of yeeeeeeears?” He followed with a series of statements about being together: “I cannot understand how…it occuuuuuuurred, but we are here. Here, in this dirty room.”

Then, to rising laughter, he chanted, “This fucking fiiiiiiilthy room. With the o-possums. And the vermin crawling high. But I do not care. I do not care. All I care is that we are HERE NOW. We have heeeeeeere. So thank you.” He then led the crowd in a rousing call-and-repeat offering thanks for the Off Center.

Graves’s ode impressed COPAD Madge Darlington. “He was expressing gratitude for the space,” she said. “It was such a love letter to the space.” For her part COPAD Shawn Sides said with a laugh that watching the show was about “mostly resisting being sad.”

Lana Lesley, another COPAD, is at work on the second installment of Perverse Results, titled Grageriart, with Not Every Mountain composer Peter Stopschinski, directed by Paul Soileau. It’s slated to have a one-night workshop showing in August at a venue in Austin to be determined. From Lesley’s perspective the upcoming piece, which she described as a deliberately absurd musical adaptation of an IKEA catalogue, doesn’t relate to Not Every Mountain. And she said that though the Rudes are between spaces, she doesn’t feel this is an especially transitional time. She did concede, though, that both plays “investigate impermanence, and we are literally dealing with impermanence this very moment.” She noted that Grageriart in its current form is “purposely very compact, lithe, and mobile.”

Stopschinski, whose score for Not Every Mountain incorporated programmed synthesizers with scales built around the Schumann resonances—frequencies in the Earth’s atmosphere, raised enough octaves to be audible—reflected that losing the Off Center has made the Rudes stronger, comparing them to a rock band.

“It’s like we’ve been freed,” he said. “Instead of giving up, we’re expanding what we do. A band’s not tied to their rehearsal room at all.” Graves also referred to the Rudes as an itinerant troupe. “In some ways that’s what the piece is about,” he said in early March, when asked about the experience of creating this show while also preparing to move. Graves added, through tears, “People coming together and making something, and it disappearing. Also the set design addresses this idea of portability: It’s made from packing materials, and it’s designed to pack and be transportable—so, like, constructing our new home that we can take with us.” After the run, again emotional, he described the experience of putting together the show as a “two-month-long benediction for this space.”

Having an established place to work is actually part of the organization’s stated mission; Rude Mechs pledges to provide “free or low-cost work space for artists of all disciplines.” As Darlington pointed out, “We’re experimental theatre in that we run experiments.” Many of those experiments have been possible only because of the freedom they had at the Off Center: constructing a Tesla coil for Requiem for Tesla, for instance. “We need real makers’ space,” Darlington said.

The Rudes’ building, whose prior lives ranged from a feed store to the home of an anarchist collective, was ideally located. Nestled beside the light rail tracks and next to the elementary school, it was easily accessible and within walking distance from some restaurants, but set back from the street so that on a show night it had the area all to itself. It will be hard to replace, but they’re looking for a new home that will give them freedom to experiment and will allow them to make space available to others. To that end, in June the company opened Rude Studios, 5,000 square feet of temporary rehearsal space in the Austin American-Statesman’s warehouse, which they’re renting at low rates to members of the city’s arts community while searching for a more permanent venue that can also accommodate performances.

As the Rudes pursue a new Texas home base, they’re making more plans to take their act on the road, another large component of their mission. Joseph Haj, artistic director of the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis, met with Graves and Sides in Austin after the run and expressed interest in potentially helping the Rudes complete Not Every Mountain, even possibly staging it at the Guthrie.

In the meantime the group packed as many events and performances as possible into the Off Center’s last days, culminating in May with a yard sale and a final farewell shindig, a “Buh Bye ‘Bonfire’ Party,” filled with dancing and debauchery, even a special ramp that brought revelers to the roof.

Austin theatremaker Katie Van Winkle, who’s worked with the Rudes on a number of projects and appeared in the troupe’s reconstruction of Dionysus in 69 (originally created by the Performance Group, predecessor of the Wooster Group), recalled that as the night pushed on, well past the posted end time of midnight, she and others stuck around, no matter how tired they got. Van Winkle said they found themselves thinking, “What if we stay here forever? What if we never leave? What will they do to us?” Yet in the days following the farewell event, Van Winkle discovered new signage indicating that the Off Center was now off-limits.

But the Rudes were one step ahead. Around 9 p.m. on the night of the party, Lynn addressed the attendees, standing above the stage of the space the company had called home for close to two decades, and flipped the meaning of “Off Center.” From almost exactly where he’d sat during Not Every Mountain, he declared, “Anybody here, you text them or you call them, you say, ‘I need to go to the Off Center,’ and that’ll be a callout to say, ‘I need to go to a place where I just feel welcome, not just the part of me that you accept, but the part of me that you don’t accept, you don’t even know—the weirdest part of me.’ That place, this clubhouse, has been that for us; you could go to this place and just be accepted as your full self. And so with that in mind, I want to change what it means to say, ‘We’re going to go to the Off Center.’ I want to invite you all to say…” He picked up a glass and uttered a toast that doubled as a stage direction: “To the Off Center.”

By redefining the name of the theatre, from his perch Lynn echoed the final lines of Not Every Mountain, which he’d spoken from nearly the same spot, making good on the claims he made in those last moments of the piece:

Our mountains are permanent.

Our churches are permanent.

Our theatres are permanent.

Our marriages are permanent.

Our friendships are permanent.

Our countries are permanent.

The only thing not permanent

is our understanding

of what anyone could possibly mean

by the word “permanent.”