Doing The Grapes of Wrath for the first time helped us realize that you can travel a thousand miles by crossing 30 feet of stage floor. —Frank Galati

The journey of bringing the theatrical production The Grapes of Wrath to the stage in many ways mirrored the Joads’ struggles at the heart of the original story. When the Steppenwolf ensemble set out to realize this conquest, they could not possibly have surmised the enormity of the task that they had laid out for themselves, or the shared devotion that it would take to move this play through a lengthy development process from the original run in Chicago to the eventual triumph on Broadway. The play had been commissioned in 1985, but did not open in Chicago until September of 1988, so the path was not only filled with a myriad of bumps and grinds, but also required a perseverance that was truly remarkable. Ensemble member Frank Galati, who adapted the novel for the stage, shares his memories of the first discussions about the possibility of doing The Grapes of Wrath:

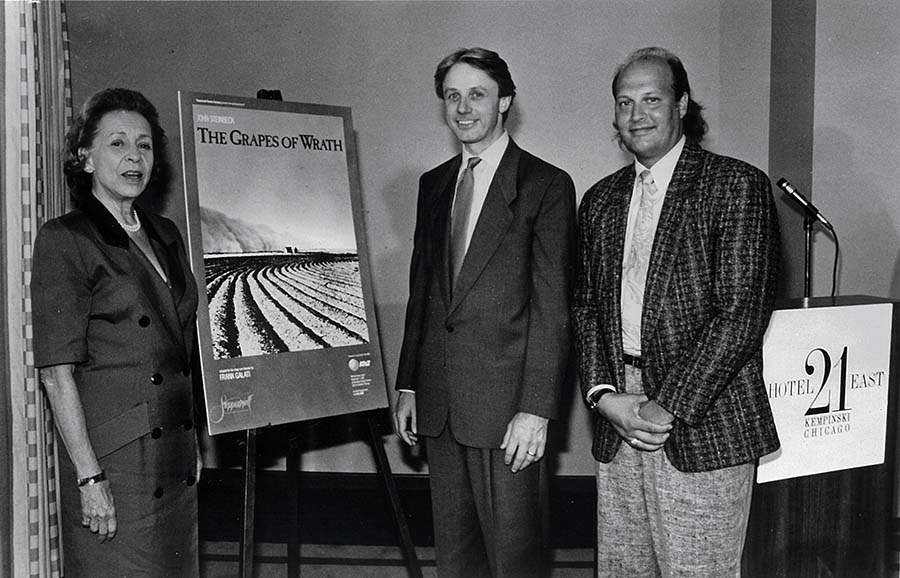

I was still rehearsing You Can’t Take It With You at Steppenwolf, when Gary [Sinise] said, “You know, you ought to think of something that you would really like to do that you think would be good for a big ensemble.” I said, “Gary, what about The Grapes of Wrath?” I can still see his face. His eyes lit up. He instantly knew that it was a good idea. By that time the company had a New York reputation, so when the publisher went to Mrs. Steinbeck and said Steppenwolf Theatre Company in Chicago wants to do an adaptation of The Grapes of Wrath—she had seen Balm in Gilead or True West and was very impressed, so she gave us rights to do it. We sent her the script and she approved it and became one of our most passionate advocates and supporters.

Galati continues on about the difficulty he faced in the process of adapting the script:

Once we got permission from Elaine Steinbeck, Gary said he wanted to direct it, and I thought, “Fantastic.” I started to work on the adaptation. I didn’t get very far. I never got a full draft. I didn’t let myself think about what the physical production was going to be, because Gary was directing it. I was only thinking about the storytelling and the text, and for some reason that kind of gave me a block. Then Gary resigned from his artistic directorship and moved to California and began his career in Hollywood. Jeff Perry took over as interim artistic director, and he said, “Gary is gone. You’re going to have to direct it. You have to keep writing it, and you’re going to have to direct as well.”

It completely freed me, because I immediately thought of how to do it, which I didn’t let myself think about. I thought, “I know how to do this. I need a bare stage. I have to have a truck. I have to have fundamental elements of earth, air, fire, and water. That’s all I need.” Then came the whole idea of music to drive the story—to be the engine that moves the truck to California. I got turned on to composer and performer Michael Smith, who just sort of blew me away with his beautiful, sultry voice. I thought, “What the fuck? I’ll call him.” He didn’t know me, but I called him up and said, “Michael, have you ever thought about composing for the theatre?” He said, “No, but I’d love to.”

We never had a workshop. We never even had a reading. Who would do an epic play that is God knows how long based on the number of pages without actually reading it out loud? The first reading of the text was the first day of rehearsal.

The first steps in moving forward were the continuing work on script development and the all-important casting process, which was complicated by the fact that the show had far more cast members than there were ensemble members. This would be the largest cast in a Steppenwolf show up to this point in its history. Phyllis Schuringa, who was the assistant to the artistic director, became, out of necessity, a kind of ad-hoc casting director, which would become a more formalized position when Martha Lavey took over as artistic director in 1995. Schuringa remembers the daunting task of casting Ma Joad:

We didn’t know anybody in Chicago. I started calling casting directors in New York, and they would say, “You know I get paid for this, don’t you?” And I said, “Yeah, but in your dreamy dream casting of The Grapes of Wrath, who would be your Ma Joad?” We were trying to get them excited by the project. Eventually, Lois Smith started coming up over and over again. We decided to fly Lois to Chicago to have her meet with Frank. Flying someone in for an audition was quite an ambitious move for us at that time. Lois couldn’t have been more gracious. Frank met with her, she auditioned, and the choice was perfect.

Galati adds:

Vividly etched in my memory was entering the office, turning the corner, and there was this woman sitting on this sofa. It was Lois Smith. I had no memory of what she looked like and I wouldn’t have recognized her, but she was so magical in her presence sitting there in the office that she kind of knocked me over. Lois read some scenes or some speeches and we cast her instantly. She was shocking. She was so real. Lois was so much in the aesthetic of Steppenwolf. She had that unspoken commitment to truth and to honesty in acting, the relentless interrogation of one another’s inner truth.

The equally significant role of Tom Joad was yet to be cast, as Galati explains:

We’re auditioning and putting the cast together and Randy [Arney] says, “Who are we going to get for Tom Joad?” I said, “I think we should ask Gary [Sinise], because he was the father of the project. He was the one who said yes to it and who launched it, and he’s perfect for Tom Joad.” Of course, in those days, he wasn’t a big television star yet. He had lots of irons in the fire, but it wasn’t as difficult for him to say, “Okay, I’m going to do a gig at my home theatre, and I’m going to play a role.” There was no idea or ambition that it was going to go beyond playing here in Chicago. We didn’t have a clue.

One last addition to the Chicago cast of The Grapes of Wrath was John C. Reilly, in one of his first professional theatre roles as the mentally challenged Joad brother, Noah. Schuringa found Reilly when she observed the final class projects of the students at the DePaul School of Drama in Chicago. Subsequently Reilly had done some work with “Page to the Stage,” which was an early forerunner to Steppenwolf’s Theatre for Young Audiences program that was set up to introduce area school children of all ages to the theatre.

With casting in place, the focus shifted back to the ongoing development of the set design and script. Kevin Rigdon was once again tapped to be the scenic and lighting designer for the production, as well as codesigner for the costumes. Rigdon fondly remembers:

Out of all the new plays I’ve ever done, The Grapes of Wrath was the most unusual way of working. The design of the show came before the script. Frank and I met in my office in the scene shop and looked at pictures and talked about things. I went out into the scene shop and beveled some pieces of plywood and came back in and stuck them in the box in response to the Dorothea Lange photographs entitled The Cultivated Fields. By the time we were done that day, we had a schematic design for the show that Frank took with him as he wrote the script.

Randall Arney, who would become the artistic director in 1987, provides his perspective on the preview process in Chicago:

The Grapes of Wrath, the collaborative nature of how a project of that magnitude came together artistically, is amazing. The show took the biggest leap artistically on Friday night of our first week of previews. We had two shows on Saturday, four hours apart. We’d already sold the tickets. The audience was coming. Frank cut—it was “the night of the long knives.” He came in the next day, and he’d cut 50 total pages and another 50 other pages had cuts on them. By having him go through it and deciding what was truly important—it was like polishing a diamond. Frank literally did this in one night. The next day the whole cast sat in the auditorium at the Royal George and Frank talked everybody through the cuts. Rick Snyder raised his hand and said, “Do I still need to come? I’m happy to.” We realized at that point he had been cut from the show entirely. We reworked it so that Rick was playing some other parts. It was about serving that thing. It was an incredible process and such a journey.

Galati also describes the fortitude of the company to work on The Grapes of Wrath and bring it to a place that the company truly believed it was destined to go:

There’s no point in playing a four-hour play when you know it’s got to be cut. So why play what we’re going to lose? I handed out cuts before the first show and everybody is looking and they’re reading, Al [Wilder] was berserk, because the Muley scene at the beginning of the show had been cut so much. That was sad, because it is a truly gorgeous scene in the novel.

I realized instinctively the purity and the simplicity of the opening of the simple Steinbeck narration from the text. I did not choose the very first words of the novel, but rather three or four paragraphs into the narration at the beginning, and the line is, “The dawn came but no day,” and then it goes on.

The Joads’ struggle did not fit the journey of Steppenwolf completely, because there would indeed be a Promised Land for this production, but the journey was just beginning. Despite all the passionate hard work leading up to the opening in Chicago, critic Richard Christiansen, who had been instrumental in giving the company much-needed attention in their earliest days in the basement in Highland Park and had generally been one of their biggest champions, pulled no punches in the opening lines of his Sept. 19, 1988 Chicago Tribune review of The Grapes of Wrath:

It takes a very long time for Steppenwolf Theatre’s The Grapes of Wrath to finish, and when it is all over, in director Frank Galati’s reverent and ambitious adaptation of John Steinbeck’s novel, admiration for its effort must give way to disappointment for its results . . . For a production graced with some of Steppenwolf’s best actors, Grapes of Wrath has amazingly little to offer in strong performances.

Hedy Weiss’s passionately worded Chicago Sun Times rave was in sharp contrast:

A cry for social justice and compassion, and a hymn to the endurance of the common man, Steppenwolf’s production of The Grapes of Wrath is also a celebration of theatre as a place where great stories must be reenacted. The play is here for only a limited run. But it would be an unpardonable sin if it did not receive an extended life, both in this country and abroad.

The impact of the critical response on Steppenwolf’s endeavors provides a fascinating glimpse into the role of the critic as a positive influence on the artistic process. That seems to be particularly true in the case of The Grapes of Wrath, where Weiss’s review provided hope and belief, and Christiansen’s written assessment gave the company an honest view of issues that needed to be addressed if the show were to move forward.

Steppenwolf moved ahead with plans for The Grapes of Wrath, finding an ally in artistic director Des McAnuff at La Jolla Playhouse who provided a home for the continued development of the play. In a rare collaboration between regional theatres, La Jolla Playhouse included the show in its 1989 subscription season. This was followed by a run in London at the Royal National Theatre of Great Britain’s Lyttleton Theatre, which included another complete rehearsal process and ongoing cultivation of the script. Terry Kinney talks about the La Jolla Playhouse run:

There was a confluence of styles that didn’t merge with each other when we were finished with the run in Chicago. They were interested in taking it to La Jolla, and that’s when Gary said, “We have to ask Frank to take us back to the novel and get rid of everything and go back to the actable parts of it and make it realistic.” Frank happened to be thinking the same thing, so we start working together on the page, rehearsed it [in Chicago], but by the time we opened in La Jolla, it was a whole different animal. Frank stayed for the run and kept adapting. Then on to London where we had a short rehearsal period and kept growing the piece into the more pared-down essentials of the mythology coming out of the realism of it. By the time we were in London, it was at its peak, and then coming to New York was the gravy.

Lois Smith speaks about the Steppenwolf ethos and how ideas from unexpected sources resolved an unsettled moment at the end of the play:

We had taken The Grapes of Wrath to La Jolla and continued to work on it. One night somebody’s friend came to the show. There had been a section that was extremely hard to figure out where the family moved from the boxcars at the end. It was a desperate time after Rose of Sharon had lost the baby. There’s a horrible storm and so they leave the boxcars in this terrible weather and end up in a barn. There had always been this problem about how to make that transition work. We tried so many things. I remember days of rehearsal in Chicago just trying something else to find the key.

This friend said something like, “I wondered why they left the boxcars—the boxcars were so comfortable.” Sally Murphy [who played Rose of Sharon], Gary, and I talked about it at a restaurant in La Jolla and took it in. Of course, the boxcars are flooded and somehow it hit us all, “Oh my God.” That somebody could have that response, “The boxcars were so comfortable.” I think Gary got up and called Frank. We immediately altered a few things the next day.

There were two little children’s swimming pools set up on the two sides of the wings, and during the narration, Sally and I rushed offstage, immersed ourselves in the water and were drenched. We came back for the exodus from the boxcars, all comforts were removed from the boxcars, and we couldn’t have been more miserable. The end moment was always wonderful, but the trip from the boxcars to the barn had always had been problematic, and now we finally knew how exactly to make it work— how to make us miserable enough, and it came from that little comment.

The time at the La Jolla Playhouse provided the creative team with an opportunity to step outside of the project, by virtue of a new location, and gain much needed perspective as they crafted the show into a more fluid piece of theatre for their ongoing pursuit of a New York run. Arney speaks of the importance of the London run of The Grapes of Wrath:

A friend of managing director Steve Eich named Thelma Holt was running an international theatre festival at the National Theatre of London. We could get only 10 performances, so we built two sets—one in La Jolla and one in London. We took 30 people and did the play at La Jolla, and then flew the cast to London. La Jolla got us the rework we needed, and the London reviews got us into New York.

With financial backing from AT&T and some ardent Steppenwolf supporters, The Grapes of Wrath opened to glowing reviews in London, and Steppenwolf was the first American theatre company to ever play at the National Theatre. Longtime London theatre critic Jack Tinker’s review in the London Daily Mail in early June of 1989 unhesitatingly validates that Steppenwolf’s hard work had paid off exceedingly well:

The Grapes of Wrath . . . is as shatteringly a perfect piece of American theatre as you are likely to experience in a lifetime of trans-Atlantic travel.

John Peter, writing for the Sunday Times, added:

It is the best kind of American acting, gritty and gnarled with a simple rhetoric, which knows that it has no need of bombast or hysteria. The actors are sharply individualized and yet self-effacing.

By the time of the London run, even Richard Christiansen had come full circle in his assessment:

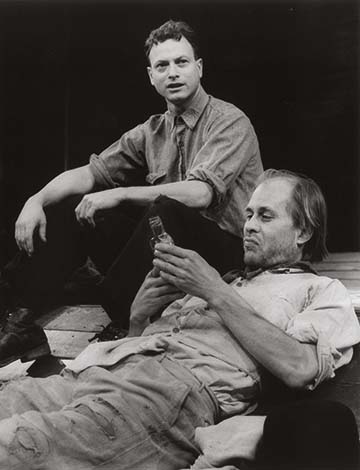

Gary Sinise, as the embittered Tom Joad, stands as the powerful focus of Steinbeck`s anger against social injustice. Jeff Perry delivers a heartbreaking portrayal of the Joads’ retarded son Noah, and Tom Irwin, in a smashing bit of virtuoso acting, searingly portrays a farmer driven mad by the despair of poverty.

Kinney shares a moving recollection of closing night of the London run that symbolizes the level of respect and admiration that Steppenwolf had garnered:

The most glorious moment I ever had in my life as an actor was the closing night in London. We didn’t know that everybody in the building was so fond of us. Thelma Holt, who eventually was part of our New York experience too, was this lovely old-school British producer who arranged on closing night as we were taking our curtain call for roses. I can’t tell you how many roses were dumped out of the grid onto us, but we were up to our knees. The entire stage just rained down with roses on us.

All that remained in this lengthy journey was bringing the show to Broadway. In the minds of most ensemble members, “making it on Broadway,” although a fantastic achievement, represented, more than anything, an opportunity to share their work with an even greater audience for a play that they felt warranted a special level of recognition. Even today, most ensemble members continue to call Chicago home, even if the myriad opportunities that have accompanied their successes have taken them beyond the city’s potential to fill their creative needs.

Frank Rich’s March 23, 1990 review in the New York Times for The Grapes of Wrath provided icing on the cake, but further indicated the values at the core of the Steppenwolf Company—values that still drive them 25 years later:

As Steppenwolf demonstrated in True West, Orphans, and Balm in Gilead—all titles that could serve for The Grapes of Wrath—it is an ensemble that believes in what Steinbeck does: the power of brawny, visceral art, the importance of community, the existence of an indigenous American spirit that resides in inarticulate ordinary people, the spiritual resonance of American music and the heroism of the righteous outlaw. As played by Gary Sinise and Terry Kinney, Tom Joad and the lapsed preacher Jim Casy—the Steinbeck characters who leave civilization to battle against injustice—are the forefathers of the rock-and-roll rebels in Steppenwolf productions by Sam Shepard and Lanford Wilson just as they are heirs to Huck and Jim. They get their hands dirty in the fight for right . . .

Like the superb Miss Smith, Mr. Sinise and Mr. Kinney, the other good actors in this large cast never raise their voices. Such performers as Jeff Perry (Noah Joad) and Robert Breuler (Pa Joad) slip seamlessly into folkloric roles that are permanent fixtures in our landscape. They become what Steinbeck believed his people to be—part of a communal soul that will save America from cruelty and selfishness when other gods, secular and religious, have failed.

The New York run of The Grapes of Wrath and the acclaim that came with it further cemented the company’s place as a leader in the Chicago theatre community and helped to provide a symbolic foundation for the final phases of construction of their own theatre building. The intrinsic problems of the great success that accompanied their meteoric growth through the 1980s made the move to a new space absolutely essential to the theatre’s ongoing survival. The theatre, for all intents and purposes, was busting at the seam. Arney summed up the massive company growth of the 1980s:

We won the 1990 Tony Award for best play for The Grapes of Wrath. The following year we opened our new theatre space at 1650 N. Halsted. Starting in 1985 when there was nobody around to 1991, and having the new building and the Tony Award, ended for the first time the lingering existential question about our staying power, “Is this company going to be here a decade and then stop?” We weren’t asking ourselves that question anymore.

This piece has been edited and excerpted from chapter three, “Transitions, The Grapes of Wrath, and a New Theatre,” of Steppenwolf Theatre Company of Chicago: In Their Own Words by John Mayer.