"Because things are the way they are, things will not stay the way they are," Brecht once wrote. We asked a wide cross section of the nation's playwrights and artistic directors—those who write plays and those who program them—how they are planning or intending to respond to the election of Donald Trump to the U.S. presidency as theatre artists and leaders, and what they think theatre can do to shape and direct the national conversation. The first half of the responses is below; Part 2 is here.

An Urgent Task Ahead

What can theatre do to address this moment? Recognize that it is only a moment. Summon moral courage, both to learn from the history that led up to the moment, and to plan the next moment.

I myself must begin from a place of moral humility as a cisgender white heterosexual man whose many forms of privilege are part of the problem: They insulate me in some measure from what is to come and make it harder for me to see what must be changed. I was surprised and sad on Nov. 8, out of my naïveté about the depth of our nation’s divisions. Friends of mine—especially those identifying as people of color, women, disabled, or LGBTQ+—were not surprised, though they were certainly sad. They were not surprised because they have seen it before.

It is painful to accept, but certainly true, that our culture, including the nonprofit theatre, generally fails to illuminate, interrupt, and bring redress for the racism, religious bigotry, sexism and misogyny, homophobia and transphobia, nativism, ableism, classism, and ageism that are and have been abroad in the land, including in this election.

Responsibility for such failure rests largely with people like me, and the problems we bequeath to the future will not be undone in my lifetime. That only makes my task more urgent. Organizing structures of the nonprofit theatre generally mirror all of the systemic oppressions ascendant in this election. To paraphrase the parable: Better I should tend to the plank in my own eye before I worry about the speck of sawdust in my sibling’s.

Therefore, the highest and best use of my time is to champion the voices of diverse theatre artists and managers and audiences whose lived and imagined experience—vastly different from mine—will reveal and over time redefine the open-hearted, humanist center of our culture, onstage and off.

It is also my joyful obligation to put my privilege in service of equity and inclusion at Yale Rep, and throughout the conservatory at Yale School of Drama; to share leadership with colleagues across traditional bounds of hierarchy; and to wind down cycles of repression by advancing leaders in every discipline of the art form who are self-aware, empathetic, and thereby prepared to raise the standards of theatre practice around the world.

Beyond the workplace, my challenges are ever more vivid and pressing: the current promises and appointments of the President-elect herald exclusionist government doing harm around the world to vulnerable populations and the planet. Such forces of authoritarianism and barbarity are to be resisted in service to democratic institutions and humankind.

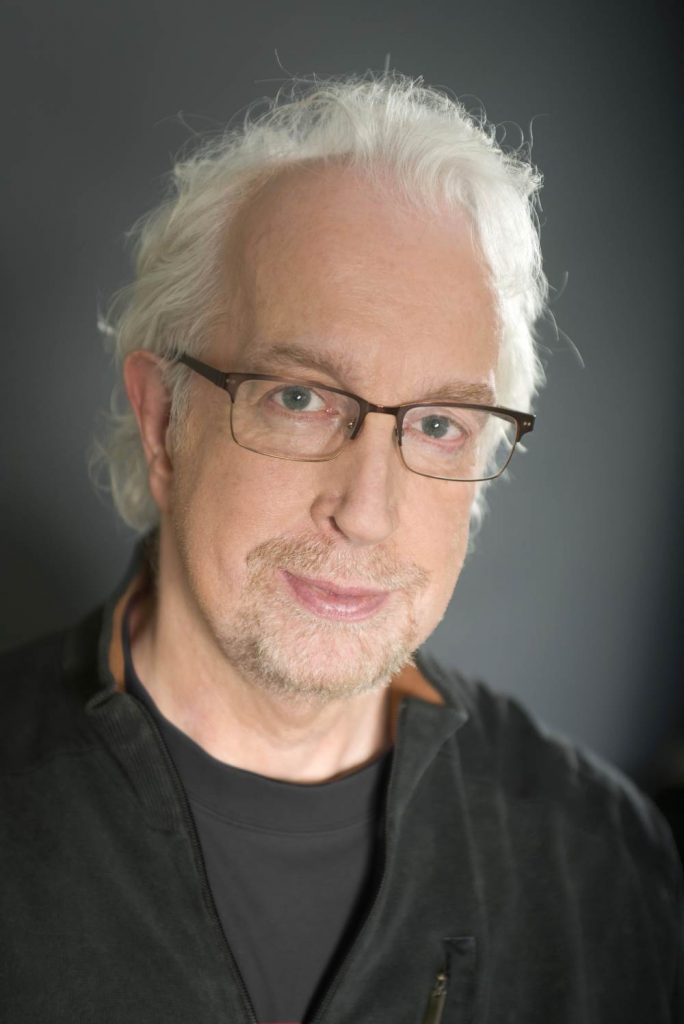

James Bundy, artistic director, Yale Repertory Theatre

New Haven, Conn.

Wide Awake in America

In this moment…

As a professor, I’m pushing my students to become more actively engaged with the social and political realities of this new world order. I encourage them to shift their settings from autopilot and actually experience navigating the turbulence; look, listen, then respond with tools of resistance: a pen, a paint brush, a camera, a musical instrument, or even their own bodies. The only thing they can’t do is keep their eyes shut. This is a moment when all of the synapses in our bodies should be firing, and responding to the unfolding events with action and intention.

As a theatremaker, I will to continue to develop OUT/LET, a site-specific multimedia performance installation set in Reading, Pa., a social sculpture designed to foster an environment where art and community meet. This spring OUT/LET will occupy the abandoned Reading Railroad Station, transforming the historic space into a dynamic performance installation that explores the diverse voices of people in the economically strapped city. Using as our foundation the hardships, challenges, and triumphs of people living in and around the post-industrial city, the installation will weave their individual stories into one cohesive tale of the city. We want to capture the collective voice of a community that is grappling with how to reclaim a narrative that has been fractured along racial and economic lines. The goal is to place disparate members of the community directly in dialogue. We began the project more than three years ago, and now in this fraught political climate it has taken on even more urgency and necessity.

As a parent of two African-American children, I will make their happiness and safety my priority, fighting to ensure that this remains a country where they can thrive and shape their own future. Silence is not an option; my ancestors fought too many hard ugly battles for social justice for us to remain complacent.

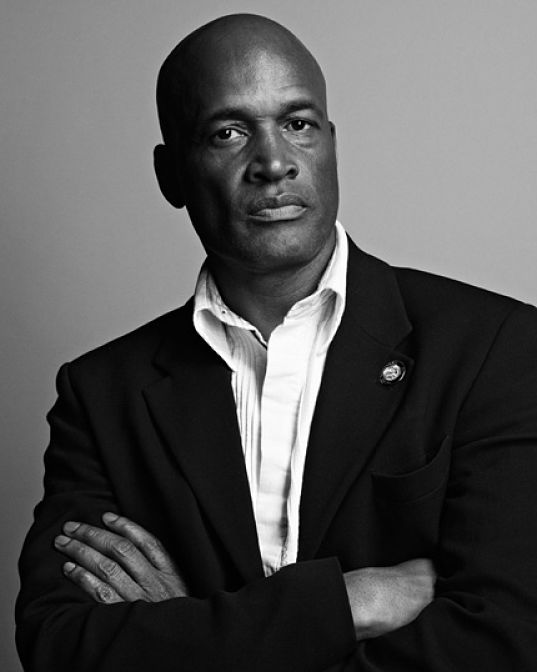

Lynn Nottage, playwright

Brooklyn

Complicity and Community

I think the most pertinent work for us right now is to prepare the human heart for expansive empathy by creating profound and beautiful art. But that alone is not enough. To channel and direct that energy, we first need to prepare ourselves to stand up against bigotry and prejudice. We must turn the mirror back upon ourselves. We might indict our government for failing to protect the human rights of all Americans, but how is our industry responsible for romanticizing what amounts to human rights violations, or for rewriting history so that it is more palatable or convenient, further placating and anesthetizing audiences? What too many producers refuse to consider is our own culpability in propagating stereotypes and untruths, and how these in turn reinforce an unequal and unjust society. We are not innocent, and recognizing that gives us powerful grounds to take a stand and make a real difference.

The stakes are too high to permit any prejudice to go unchecked in our names, in our theatres, onstage or off. Let’s imagine new partnerships that nourish the diversity of our communities. Imagine a coalition of theatres across the country working to protect the human rights of all people. Imagine a manifesto to which we can hold ourselves and the great numbers of people we touch through our work accountable. We are the vanguard of innovation, creativity, and imagination; let’s not allow ourselves to be bullied into thinking the only way to make money is to trade in stereotypes and further desensitize our audiences.

Audiences are hungry to learn! They want dynamic theatre experiences; they want to reach across that deep, painful divide toward other human beings in a common experience. Now more than ever, they want to be invited in, troubled, reawakened. They want to be part of the solution, and solutions exist where we meet, not where we diverge. Let’s lead. Together. There is no other way forward.

Sarah Bellamy, co-artistic director, Penumbra Theatre

St. Paul, Minn.

In Defense of Grief

“Don’t mourn, organize!”

It’s an old American Leftist saying, usually attributed to Joe Hill, enjoying new popularity this post-election season. My grandparents, who identified as Communists, lived this mantra. In the Old Left, displays of emotion were considered weak, or—far worse!—bourgeois. Each comrade is a limited resource, and time spent in sadness is time lost on the long road to revolution. For my grandparents, this stoicism extended to their personal lives. When I arrived at my grandmother’s apartment hours after my grandfather died, she caught my eye and said, “There will be no crying.”

I don’t want to encourage any lazy clichés about dogmatic, bloodless communists here; my grandparents were the life of the party. They were funny, they were frankly sexy in a way that scandalized me as a child, they loved theatre and music, they swore and argued with multiple generations of friends and family well into their 80s. They endured personal hardships, including arrest and the blacklist, because of their fervent conviction that the poor deserved better. From the perspective of this granddaughter, they were completely fucking fabulous.

But they also believed that grief is antithetical to progress. And this mistake, I think, is directly related to their lifelong inability to fully countenance the horrors perpetrated under Stalin, and to change course from their fidelity to the Soviet Union, no matter how belatedly.

Joanna Macy, a Buddhist scholar and ecology writer, has observed that when it comes to climate change, what prevents people from getting involved in activism is usually not apathy but the fear of facing their overwhelming grief. And it is overwhelming. Not just climate change, which deserves a special prize for overwhelming-ness, but the potential horrors that vulnerable populations will face under a Trump administration. If we are to confront these threats clear-sightedly rather than sentimentally, then how can grief not enter powerfully into it?

Mourning may carry the connotation of resignation, and despair is paralyzing, but grief can be galvanizing. Think Antigone. If we are going to meaningfully resist, as activists and especially as artists, we need to keep an open channel for grief, though it may render us temporarily disoriented, daunted, even ridiculous. A week or so after the election I gave a lecture at a community library, and in the last few minutes I unexpectedly became incapacitated by sobs. It was embarrassing. I hope it doesn’t happen again any time soon. But I did eventually get through it, and so did the admittedly uncomfortable audience. At least they knew I was awake.

Amy Herzog, playwright

Brooklyn

Trust, Not Fear

The morning after the election, I felt like a fool. As all the articles started pouring in about how the media had completely “missed it,” I looked at my own leadership in the arts, and thought: I missed it, too. How many times have I articulated that the A.R.T. is dedicated to building community, to provoking dialogue and debate, to creating empathy with points of view different from our own? But on Nov. 9, it became clear that that community, that conversation, and that empathy had clearly not extended to an enormous portion of America.

The conversations with my colleagues at the A.R.T. on the day after the election were driven by shock and disbelief at the results. But given that more than 62 million people voted for this result, any feeling of being “stunned” only reinforces how embarrassingly out of touch we have been. As the articles shifted to talk of being trapped in “echo chambers,” I started to think about what kind of “echo chamber” we unintentionally have created at the A.R.T.

We are now awake. We may not have the answers, but there are urgent and pressing questions that we must ask anew as theatre practitioners: Who is our audience? Who are we making theatre for? Whose stories are we telling? What are the stories we need to be telling now and why? What is the role of theatre in our democracy? What would we do if President Trump attended a show at our theatre? In the face of the hate crimes that have happened in the aftermath of the election, how do we most effectively fight and stand up for the values of inclusivity and equality? How do we foster truly healthy discourse and a mutual respect for our differences?

I know we have a rough journey ahead, filled with uncertainty. But when has that stopped us in the past? We constantly immerse ourselves in a creative process that is defined by navigating uncertainty, traveling into the unknown, and overcoming challenges and obstacles. We work with dogged perseverance and determination to never throw in the towel. We strive to create an environment of trust, not fear. As artists, we transcend our own experience and become empathic and compassionate to others. We listen generously. We move with courage and resilience. With every project, we bring people together who are strangers and turn them into families; with every audience we build a community.

And through it all, we aspire to work with an open heart, for we know that therein lies the potential for transformation. All of this is in our DNA and our muscle memory; it is our expertise and our unique training. Now is the time to use it, not just for making theatre, but for the future we all face together. In the words of Toni Morrison: “This is precisely the time when artists go to work, there is no time for despair, no place for self pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.”

Diane Paulus, artistic director, American Repertory Theater

Cambridge, Mass.

Who We’ve Failed

I was meeting with a group of playwrights the day after the election, relieved and ready for their insights. What are we going to do? How are we going to save? Surely I would find refuge in like-minded artists and we would solve this together. We’d at least share ingredients for the first layer of the salve.

As many of us—black, Latinx, Asian, and white—were in mid-conversation around our collective concerns and outrage about the President-elect and his divisiveness winning over masses, a Native American colleague sat politely quiet. Eventually our outrage induced her own. “I don’t understand why you’re so outraged NOW,” she challenged us. “My people have been under attack for numerous administrations in this country and no one seems outraged by that.” She wanted to know how we could be so surprised, as if this current election provided new information rather than merely serving as confirmation for some very old and established social and systemic behavior.

I have to say her question silenced some of us, shamed and/or ignited the rest of us. There was something fundamental in her questioning about how easy it is to dismiss the oppression of others when you are overly consumed with your own.

I see my new role of playwright as more of a continuation than any need to go in a different direction. I was concerned about housing discrimination, worker’s rights, poverty, racial injustice, violent policing, and gender identity bias before the presidential election, and will continue to be. My lens is simply becoming sharper.

Many will now be interested in telling the stories about those whom they feel we missed in this election, often pegged as the white working class. I consistently hear this group being described as “the people we failed,” as if they’re now the only folks who represent poverty and a biased system of class hierarchy. What I hope to see is a tackling of this ideology and the creation of a balanced vision of who is represented in working-class America.

I hope theatre will serve as a platform for some very uncomfortable programming. Perhaps the plays will be a little angry, less “complete” in their perspectives. We’re still in the thick of it and don’t have time to wait for perfect clarity before building stories around these issues. What I hope we gain from our field is a willingness to demand, at the highest theatrical levels possible, stories from those whose oppressions are socially muted. Let us hear stories about indigenous peoples or immigrants or the working class without putting conditions on the work or deciding that it be delivered to us through a white elitist gaze, or that our work should somehow satisfy a pseudo “universality.”

The more honest we can be in our storytelling without having to satisfy the biases of audiences that may be as divided as our nation, the more impact we’ll have as a theatre community in creating a culture of national understanding and unity.

Dominique Morisseau, playwright

New York City

Heat and Light in the Darkness

As I write this, it has been nine days since the election. Many members of my staff (especially people of color, women, gender-fluid, and LGBTQ staff) are viewing the future with tremendous concern. My children are witnessing, for the first time in memory, athletes of color at their high school suffering racial taunts and transgender and Muslim students receiving threats. The temperature at the North Pole is 36 degrees above normal. And our President-elect has begun staffing his administration with individuals who can only be described as white nationalists.

What do we do? As citizens? As cultural leaders? As community members, knowing that our friends, our neighbors, our coworkers, our audiences, and supporters may have opinions in opposition to ours? How would the previous generation of extraordinary leaders in our industry—Joe Papp, Zelda Fichandler, Lloyd Richards, Gordon Davidson—deal with the monumental schism that confronts us?

As I ponder these questions, I’m reminded of a quote from Stanley Kubrick: “However vast the darkness, we must supply our own light.” Indeed, this is what art, and specifically the theatre, has done for many centuries. We cannot and must not let fear compromise our duty as artists. We must continue to speak out, to comfort and challenge our audiences, to provide both outrage and embrace, to provide a place where, for several hours, those who ask us to interpret the world around us can pause, reflect, consider.

And, in a time in which the “others” in our society are increasingly demonized or ignored, we must protect them. We must continue to honor the marginalized, and encourage our audiences to experience their stories and struggles and emotions through the most powerful weapon we have: empathy. At its best, our art form provides not just third-person narrative but first-person experience, exhorting us not just to think but feel, to connect and embrace in a very personal way with those whose lives and journeys—and yes, even political opinions—may seem foreign, or frightening, or odd.

Downstairs right now, we are having our first preview performance of A Christmas Carol, a seasonal ritual here at the Goodman for nearly four decades. Later this season, we will be producing works which focus on specific social challenges: the cynical exploitation of horrific tragedy for individual gain, the plight of refugees and their struggles to maintain personal dignity and identity amid the search for a safe haven, the challenges of family in a world rife with generational disconnect—but for now, I think that the messages of Christmas Carol are essential to a society that seems to be foundering on the rocks of fiercely clashing ideologies: The importance of generosity in an era of selfishness. The necessity of tolerance in a world plagued by demonization. The celebration of our diversity, embracing the fact that we are, in Dickens’s words, “fellow passengers to the grave.” And ultimately the power and grace of love, even as we fight to combat hatred and ignorance.

These are indeed dark times. It will get worse, I fear, before it gets better. But more than ever, our art is essential to our country and our world: to provide the “light” of anger and healing, activism and contemplation, challenge and acceptance that will, I hope and believe, overpower the darkness.

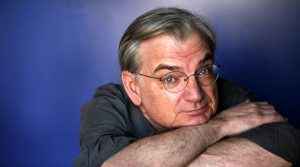

Robert Falls, artistic director, Goodman Theatre

Chicago

Anger, Despair, Also Hope

I spent Thanksgiving with my family in Scott Township, Pa., a place whereTrump signs were interrupted only by the occasional “Hillary for Prison” bumper sticker during election week. I know and love many of these people, I grew up with them, I’m related to many of them. I recognize their complexities.

Being a liberal from a swing state helps me to comprehend the blue/red divide, but I still struggle with the liquefaction of seemingly solid “purple” precepts. Firm ideas, like “racial, religious, and ethnic hostilities are unacceptable” and “open-mindedness is a virtue” and “bullying is wrong,” start to feel bendable under a President-elect whose response to such musings might be:

Even Trump Tower—whose pink-and-white-veined marble halls and gold-trimmed food court used to be a lunchtime escape from my day job precisely because it was the height of artifice, a departure from anything real—this insincere building is now a space where substantive policy decisions are being made. The fake palace has become a real one. The Player King is King. As a writer, my job is to tell the truth and entertain, but what is true in this post-election matrix?

Teaching helps. It provides a forum to explore big questions like, Where do we live? via a wide lens, and to give voice to those being targeted by the bigtoed incoming administration. Lorca’s view of New York City after the 1929 stock market crash, Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States, essays by James Baldwin, Walter Benjamin, W.E.B. Dubois and Mike Davis, Ionesco’s The Leader and Rhinoceros, Wallace Shawn’s Aunt Dan and Lemon—there are countless examples of writers who’ve captured deep, painful truths about human behavior in confounding, nightmarish times. The Cherry Orchard has proven useful in grasping how some people, when given a chance to confront inexorable change, opt instead to throw a party and dream about time travel: #MakeRussiaAristocraticAgain.

I’m filled with anger and despair but also hope. For the next four years, the bully will have a pulpit—and we will have a stage. I’m confident that bold and illuminating work will come out of these times. Theatre and politics have always intersected; both are obsessed with understanding human behavior. Both are fascinated by our basement-level fears. Artists explore the things that scare us; politicians exploit them. In discussing these ideas with my friend and colleague Christopher Shinn he noted, wisely, “Politics has to win. Art just has to tell the truth.”

Art won’t be enough. We need to crawl out of social media wormholes and volunteer; protect those who need protection. Actions, even small ones, add up. The media will continue to present us with dizzying realities; concrete actions will anchor and unite us.

Stephen Karam, playwright

New York City

Middle American Mirror

I work and live in red-state America, in the geographical heart of the United States. Greater Kansas City is home to more than 2.3 million people, and the demographic makeup of its two-state, 15-county metropolitan area closely mirrors the makeup of our country, with a higher proportion of African-Americans than the nation as a whole (nationally it’s about 12 percent, in Kansas City, Mo., it’s about 30 percent), a lower proportion of Latinos (nationally 17 percent, in K.C. 12 percent), and a lower number of people of Asian descent (2.5 percent) than the nation overall (roughly 5 percent). The fastest-growing proportion of new residents are immigrants from all over the globe.

The current chairwoman of the NEA, Jane Chu, used to be my neighbor, and our beloved African-American congressman Emanuel Cleaver and African-American mayor Sly James live nearby; I also live less than an hour from Kansas governor Sam Brownback and three hours from the Koch brothers. Kansas City, like our country, is full of contradictions as its population grows and changes at a rate that is astonishing.

What I love most about leading the LORT theatre in the region and being part of a theatre community that has more than doubled in the last 8 years is that the theatre we make speaks to audiences that look increasingly like our nation—and that means that our audience is both diverse in terms of race and ethnicity and in terms of political affiliation. Though the two urban counties voted overwhelmingly for Democratic candidates in the November election, Republicans swept offices across both Missouri and Kansas.

Unlike most of my colleagues who run theatres on the coasts or in Chicago (my former hometown), I lead a company that has the opportunity to tell stories to audience members that may have fundamentally different political viewpoints and values from the person sitting next to them.

Though personally this election was the most painful in my lifetime, on Nov. 9 we still had a show to do: Ayad Akhtar’s incendiary thriller The Invisible Hand. It was edifying and powerful to hear one of our nation’s most exciting playwright’s insightful, incisive critique of American imperialism in front of an audience that hadn’t heard a great story in months—much less a story like this. And though I am deeply, sleeplessly worried about the future of this divided nation, I realized in the theatre that the people in the room that night were the same people they had been the day before, that liberal voters sat side by side with conservative voters and shared the same experience; that the actors playing Muslim characters on the stage were still tearing through that brilliant story; and the audience, when it rose to its feet with cathartic applause, included white people, black and brown folks, LGBT men and women, young and old. It might have changed nothing, but that performance made me remember why I do this work, and why I choose to do it here.

In cities in the center of the United States, so often looked down on as “flyover,” real, valuable, changeable, diverse humans live their lives. They deserve great theatre, and they hold the future of this nation, as we learned in the new electoral math. Investing in theatre companies in “red state America” isn’t just the right thing to do—it may be critically necessary if we are to share a vision of a diverse, democratic, American narrative with people who are demographically and politically representative of our nation. Our recent election provides a greater sense of clarity of vision: that in the heart of America, great theatre—innovative, vibrant, excellent, morally compelling, passionate, entertaining theatre—might not just be necessary but also essential.

Eric Rosen, artistic director, Kansas City Repertory Theatre

Kansas City, Mo.

Two-Way Listening

So he won the election. Shock, fear, and anger morph into responses, both coherent and otherwise. And yet, while heartbreak overwhelms, clarity and renewed focus emerge as its natural counterweights. I think of how in 2002 my husband Malik Gillani and I founded Silk Road Rising as a response to the anti-Arab, anti-Muslim, and anti-South Asian hatred that followed 9/11. We had the audacity to suggest that America’s stories could be told through Asian-American and Middle Eastern-American lenses, and that people of all backgrounds could see their stories in our stories. Not by us, for us, but by us for all. Now we must ponder our response to 11/9, the day the election results became official.

American theatre is at its best when strengthening notions of citizenship and democracy. As theatremakers and political activists, we can no longer be satisfied with brick-and-mortar venues and devoted audiences alone. Cultural dysphoria has spoken. “White nationalists” envisage a newfound legitimacy, and this tale of two nations foretells decades of strife as millions of Americans feel their citizenship, and our democracy, in peril. If we hope to make change, we must leave our liberal echo chambers periodically, and engage with communities who feel alienated and disrespected by us. Not to swap slings and arrows with irredeemable bigots (that 20 percent is lost), but to engage the majority who long for understanding and hope. They will hear us if we hear them; we are only elitist and irrelevant if we remain inaccessible.

While we’re at it, how about we free ourselves from the tyranny of the fixed theatre season? Activism dies in the monotony of the production mill. Not everything needs to be fully produced. Transporting full productions is expensive and complicated. Think more mobile and minimalist. Think solo performances, staged readings, readers theatre. Think video plays and broadcast plays. Think the Internet and Skype. We have tools that were unimaginable throughout most of theatre’s 4,000-year history.

This is not a new frontier for me. In developing my play Mosque Alert, I learned that I can’t write about fear of Muslims without listening to people who actually act on these fears by resisting the building of mosques. This meant inviting them into my process by holding public conversations in 40-plus communities. It meant disseminating 37 videos online and soliciting feedback. It meant listening respectfully to ideas I find repugnant and ascribing them integrity in my writing. As a result, my play became a “safe space” for those with whom I disagree; only then did these so-called adversaries begin opening up to our side of the story.

I also learned it wasn’t failure when audience members arrived at radically different conclusions than I had hoped. Some Islamophobes felt affirmed by my play—an inherent risk, and a reminder that conflating democratic practice with consensus doesn’t work. This wasn’t always easy and I was certainly no hero. Anger often got the best of me.

But if I want to combat Islamophobia I need to engage its practitioners. You’d be amazed how black and white these conversations are not.

Jamil Khoury, artistic director, Silk Road Rising

Chicago

Disarming the Front Lines

I don’t know that an election changes what I hope to do as an artist. I live and make my work on the front lines of the culture wars in the NAFTA wastelands of North Carolina. Empty textile and furniture factories stand as testimony to the destructive neoliberal globalization favored by both Democrats and Republicans. For centuries, the elites of both parties here have tried to use identity to divide the working class. It can be a difficult place to live and to create work in. But that’s why I returned here.

The work at Triad Stage, no matter who sits in the White House, isn’t to teach folks something we learned in the big cities, but to make work that creates conversation, encourages community, and challenges conventions. It is designed to have people who disagree experience a story together and maybe, sometimes, find new common ground.

Often our work tells the stories of our looked-down-on and ignored region. Too often, I fear that our national theatre industry assumes an urban, liberal, elitist condescension towards those rural and working-class citizens who can and must be a part of the future of our country. I hope that our response to Trump’s presidency won’t be to increasingly preach to ourselves about how progressive and inclusive we are while rejecting the possibility of engaging with others we’ve deemed intolerant.

Preston Lane, artistic director, Triad Stage

Greensboro, N.C.

Plays Outlive Presidents

What now?

There is a theatre of total empathy, the kind where storytellers listen, respond, rethink our principals, and allow for the ideas of, say, half the country to influence our work. Then there is a theatre of amplification, the kind where we speak louder and bolder and heartier than ever before for the human (not liberal) values that we know to be the true stuff of heroes and heroines. I choose the latter.

Could I ever conceive of a play where a hateful racist swindler is anything but an antagonist or a joke? No. The ideas that accompany our new president are backwards and, yes, deplorable. Those ideas are not the stuff of my art. I think that it is more important than ever to tell stories of heroes who fight for true justice and equality, who stand up to tyrants, and who at least know the goddamn Golden Rule (it is golden, after all—you think Trumpy would like it).

It is more important now to cast our plays as diversely as America truly is, to project the stories of women, to stage stories of and by people of color, to tell stories of all identities, of love of all kinds, of science and reason, of native people and immigrants, of the challenging moments in this country’s battles for progress.

Which begs the question that I have been turning over for the past weeks: Is theatre itself inherently progressive? I don’t mean politically (i.e., Democratic or liberal). I mean is theatre—as an art form, as a product of its dramatic structure, as a thing born with the ancient DNA of storytelling—inescapably set to tell stories of progress? I think the answer is yes. Dramatic structure begs us to tells stories of change. Aristotle’s climactic “reversal” insists on characters and worlds that do not go backward or remain stagnant but act and react until a new order is found. Even if plays have crude or hateful protagonists, the audience isn’t convinced of their darkness by the show’s end but convinced of its opposite. Greedy, mad kings do not triumph in tragedies where their success is the terror of the watching audience (King Lear). Warmongering and profiteering men do not meet blameless ends in our great American plays (All My Sons). Racism, anti-Semitism, misogyny are the harrowing landscape of many great plays, not the heroism at their hearts. This is true from the Greeks to now, where we continue to tell stories that do not reward dangerous braggadocio and bullying, but where rebels against injustice and war prevail even if they die trying.

Our human species evolved into the instinct to tell stories and tell them a certain way. The stories that survive are the ones that show us the dangers of base behavior and/or celebrate a life of love and peace. Theatre exposes the basest human instincts; it does not celebrate them. We simply do not tell stories of remission without revelation or reformation. Regression is the stuff of tragedy, the stuff of obstacle. This is Romeo and Juliet, Antigone, Trojan Women, King Lear, All My Sons, Cabaret, The Diary of Anne Frank, A Raisin in the Sun. This is theatre: a thing that gathers the people for stories of transformation, of progress hard won, of conflict overcome, of catharsis and empathy and understanding winning out even if the protagonists don’t.

From this I take that a good story is stronger and will last longer than this new president. They always have.

So. I start every day calling a senator or two before telling myself that now is the time to write with more teeth and heart and guts and humor than I ever have.

Lauren Gunderson, playwright

San Francisco

Rivers to Cross

On Nov. 8, 2016, both nothing and everything changed. For hundreds of years, the answers have always been with the artists. Let us take our cues from the great Harry Belafonte, who has been an artist/activist since the 1950s and ’60s alongside Dr. King, and continues to do the work today at almost 90 years old through his Many Rivers to Cross Festival. A few years ago, I ran into Harry on the street and he praised one of the plays I had running in New York. When I expressed concern around some issues that I was facing, he reminded me that as an African-American director I need to always keep in mind that I am presenting Afrocentric work on a Eurocentric stage, so these challenges will arise. He encouraged me to keep on creating and putting the work out there—that art, by its very nature, is political.

Our work matters. It informs and it should inspire audiences. Through drama, comedy, music, and dance we lead the movement, and this moment in America only reminds us of what our responsibility is and always has been.

What I do know is that True Colors has been doing this work all along. For the past 15 years, we have had and will continue to have the privilege to run a theatre that looks like the world and tells stories of diversity, inclusion, and cultural understanding. We will continue to encourage people to attend the community conversations that we produce around race and difference, and engage them in a dialogue about issues that might be impacting the culture they were unaware of, or inadvertently impacting them when they didn’t even know it. We have taught and will continue to teach young people across the country the powerful words of the great playwright August Wilson and bring awareness across generations to his words, from all 10 plays, that still ring true in 2016.

Let us all use this opportunity to bring one new person to the theatre to sit in the dark next to a person who doesn’t look like them, while they experience the beautiful art we produce and impactful stories we tell collectively as a community.

There is a need for us now more than ever. In the great words of Spike Lee, “Wake up!” Come on, y’all—let’s do this!

Kenny Leon, artistic director, True Colors Theatre Company

Atlanta

Think the Long Thought

In the rehearsal room, I often say to actors: “The sound of your thinking needs to be louder than the sound of your feeling.” That isn’t to say that emotion isn’t important. Emotion is a key ingredient in our impulse to empathize. But I never want the audience watching one of my plays to listen to a character and respond, “Well [x] is just saying that because [x] is angry or sad or…,” thereby dismissing the reasoning behind what the character is saying.

Now more than ever I crave a theatre that is a space for debate—a forum in which points of view can be explained, accounted for, and clash with opposing ideas. I say “now more than ever” because everywhere I look I see dominating the conversation slogans, hashtags, tweets, abbreviated sentiments, many designed to provoke a quick emotional response rather than inspire complicated ideas. But theatre can give its makers the chance to elaborate—to put onstage long and intricate trains of thought, to make visible that which buzzwords conceal, to help us understand why people believe what they believe.

But this call for thinking does not only apply to theatremakers. It applies also to all audience members. It’s not uncommon for an audience member, on seeing a particularly excellent work, to exclaim that the work was very “powerful” or “moving” or, as I too often hear, “It gave me all the feels.” Or perhaps an audience member might applaud a work’s ideas by saying that the work “really makes us think about” [fill in the blank with a one-word distillation of an important issue, e.g., race, identity], or they might simply say that a play raises a lot of questions. But none of these responses are sufficient, as they fail to fully draw out what a play has on offer.

Plays have ideas. Plays propose in dramatic form, either explicitly or implicitly, a set of theories about how the world works. It is our responsibility as audience members to carefully consider a play and articulate its embedded ideas, especially when those ideas are different from the ideas we’re expecting a play to reveal.

Articulate them in all their intricate glory. Complicated ideas are not mere statements of what is good or bad, right or wrong. Ideas require many sentences filled with words like “if” and “when” and “but” and “however.” Once articulated, we can reckon with those ideas and perhaps reconsider our own received notions about how the world works. In this way, watching plays (or any art) can become practice for engaging with the larger world and with points of view that are not necessarily our own. To do anything less renders a good play mute.

Our feelings are very loud right now, and so let those feelings give us occasion to listen more carefully than ever to the thoughts of our own minds and the minds of others.

Lucas Hnath, playwright

New York City

Break It Down and Get Real

This November is indelibly marked in our collective memory. We are awakening to extreme divisiveness in our nation, along with publicly sanctioned violence, bigotry, and censorship.

Over the last year, I have been thinking deeply about the following questions:

- Who defines value? If value is determined by the select few who wield the financial wealth in our communities, our traditional boards, and our leadership, engaging in true change (not just surface change) is impossible. We must first acknowledge that our own field sits within a structure that benefits the few and is not speaking to our larger communities or current concerns.

- What is valued? The capitalistic idea of expansion is what is currently most valued in funding considerations. At the cost of our people and artists, we pour money into buildings that sit unused for hours/days. At the cost of a more interrogative, innovative art that captures the deepest and darkest truths our communities grapple with, we often make bland artistic choices that are easier to consume as entertainment.

As a field, we must value authentic rather than transactional community engagement and dialogue. We must recognize that we alone do not have the answers by developing true partnerships with social-service organizations that teach us cultural inclusion and responsiveness, instead of assuming that we know what they need. Most importantly, we must practice meaningful equity, diversity, and inclusion in our work and in our organizational structures. For how can we shape or advance a national conversation if we are not able to reflect this in our own practices and actions? We have a responsibility to leverage our institutional spaces toward interrogation, dialogue, and building understanding rather than letting them passively sit in self-celebration.

We must do all of this with innovative art and remember that we are the culture makers.

Henry Giroux warns us: “Ignorance has become a form of weaponized refusal to acknowledge the violence of the past, and revels in a culture of media spectacles in which public concerns are translated into private obsessions, consumerism, and fatuous entertainment.” It is now that the power and voice of the artist must ring true for all of us: to make visible what is invisible, to call out injustices, and, as my colleague Marc Bamuthi Joseph would say, “to normalize a sense of accountability to each other through the public imagination.” Let us come together in collective strength under the same roof.

Hand in hand with advocacy, institutional change, protest to raise awareness, and a commitment to equity, inclusion, and justice, narrative has the power to change values and behaviors. The friction we elicit in the conversation between performance and audience, or between differing perspectives, is essential in breaking down fear of the “other.”

Our Crowded Fire community takes this charge as our responsibility. Each day of 2017 we will continue to act toward this vision.

Mina Morita, artistic director, Crowded Fire Theater

San Francisco

Beyond Belief

Today is November 22, 2016.

Today we witnessed video footage of Neo-Nazis hailing Trump and offering the Nazi salute at a gathering in Washington, D.C. Our President-elect said nothing; he was busy lambasting leading figures of the media for being liars and not covering him fairly.

Today I received an email from a theatre which is producing my play Bad Jews, with a request. Toward the end of the play, the protagonist, Daphna Feygenbaum, says, “Now, when it’s easier to be Jewish than it has ever been in the history of the world, now when it’s safest, now we should all stop?”

They asked if I would be willing to cut that line.

Because it rings false. It is no longer true.

I’m sorry, but I can’t believe this is happening. I CANNOT BELIEVE THIS IS HAPPENING.

So. You want to know what I think theatre artists should do?

I think we should do for ourselves what we would tell theatre artists in Germany in 1933 to do: Run.

Joshua Harmon, playwright

New York City

Stay Savvy and Sharp

For companies like Hartford Stage, the questions “Why are we doing this show?” and “Why now?” will be more important than ever. And there will be a variety of completely contradictory yet equally valid answers. “Because all media lied to us and we need to tell the truth.” “Because we need to express our outrage and our fury.” “Because we need to create a better, more tolerant world within these walls.” “Because people need a good laugh more than ever.” “Because, in the face of shrinking government, corporate, and individual giving, we need to do more coproductions and sell more tickets just to meet the weekly payroll.” We will need to be provocative and bold and entertaining and very, very savvy.

Regarding my own work as a director, I’m thinking about the text and the subtext, the opportunities to leave the knives out in the open or—to paraphrase a famous quote—bury them in the whipped cream. (Eastern European artists tend to enjoy the latter. It’s in our DNA.) I’m thinking about satire and the following Muriel Spark quote: “The art of ridicule, if it is on the mark—and if it is not on the mark it is not art at all—can penetrate to the marrow. It can leave a salutary scar. It is unnerving. It can paralyze its object.” The time has come for merciless stage satire.

Darko Tresnjak, artistic director, Hartford Stage

Hartford, Conn.

Into the Bad New Days

As the brilliant historian Robin D.G. Kelly writes: “This election was, among other things, a referendum on whether the United States will be a straight, white nation reminiscent of the mythic ‘old days’ when armed white men ruled.”

The “bad new days,” as Brecht called them, that lie ahead offer us an historic opportunity to draw on and renew a radical tradition in theatre: a radicalism that has no truck with consolation or compromise or consensus; a radicalism that envisions another nation in opposition to the American dream of wealth accumulation and its nefarious consequences.

Theatre then must be a site of resistance to what dehumanizes us—resistance that is an inclusive, joyful, sexy, potent labor that frees our constricted, consumer-soaked imaginations. A praxis that is less of a “conversation” and more of a malediction (unpalatable) aimed at those in power.

So let us propose that all U.S. theatres make public their support for A Vision for Black Lives from the Movement for Black Lives. This all-encompassing vision for social justice is not about reform but rather democratic revolution; it is a foundational guide for all progressive institutions.

Now, as in the past, the most oppressed people are spearheading the fight for justice and democracy in our country and around the world. Let us show solidarity and propose that all theatres become sanctuaries to the undocumented and the targeted. Let our seasons fill with the brilliant, rebellious, oxygenated work of people of color, and especially queer people of color, who for centuries now have been conjuring up and mapping out a more just world. Let our theatres give financial support to our working-poor playwrights and make sure our administrations and boards are no longer largely white.

Let us also, as citizens and artists, refuse the false separation between the domestic and the international, just as we refuse to separate ourselves from one another or divide oppressions that are inherently entwined. While the election of Trump caused many of us to feel traumatized and violated, much of the world has already been living under the trauma and violence of U.S. militarism and enforced poverty. Like the oil pipelines currently being opposed, we must cut off the flow of arms sales and tax handouts in the billions to some of the nastiest regimes around the world. Let us force the government to bankroll our nation’s creativity and not, for instance, the brutal occupation of Palestine. Let us be at the forefront of demanding our taxes be invested in jobs, infrastructure, free theatres, free education, free healthcare, and reparations.

And finally, white artists must work to organize other white people for racial justice. SURJ, Showing Up for Racial Justice, is the kind of radical organization working to do exactly this. As Kelley says, “Exposing whiteness for what it is—a foundational myth for the birth and consolidation of capitalism—is fundamental if we are to build a genuine social movement.” The struggle against racism is an issue for all of us. It is not something we do to help others or out of moral kindness. As civil rights activist Anne Braden wrote, “We need to become involved with it as if our lives depended on it because really, in truth, they do.”

Naomi Wallace, playwright

Yorkshire, U.K.

Stronger Together

As a gay husband and father of two mixed-race children, one transgender, I was deeply shaken by the election results on a personal level.

This was a difficult year for the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. From a racist verbal assault on a company member to a feud with a local business that escalated out of control, it was a year in which we learned a lot about the challenges that our progressive community faces when it comes to dismantling white supremacy. I don’t believe it was a coincidence that it was the first season that our acting company had a majority of actors of color. It was also a year in which we expanded our leadership team to include staff members at various points in the organizational hierarchy who are not members of senior staff but who bring unparalleled leadership in equity, diversity, and inclusion. Those meetings have gotten a whole lot harder, deeper, and more effective.

I’ve taken comfort in these past weeks that we are already working on solutions to our community’s and nation’s most vital issues. Courageous, too often exhausted colleagues throughout our organization challenge all of us to create true equity, diversity, and inclusion on our campus and in our field. We are helping as part of a field-wide effort to take on climate change, and our singular identity as a large theatre in a rural location gives us a special opportunity. Many other OSF programs—including American Revolutions: the United States History Cycle, Living Ideas, Every 28 Hours Plays, Play on!, Martin Luther King Celebration, and Standing Rock Theater Action and Fundraiser—all give evidence that we are trying to live up to the social justice aspect of our mission to “reveal our collective humanity.”

And of course the play’s the thing. Lynn Nottage’s Sweat and Universes’ Party People, two OSF commissions and two of the most profound artistic responses to the current political moment I can imagine, are both running at the Public Theatre in New York, while a third OSF American Revolutions play, Lisa Loomer’s Roe, will open at Arena Stage in D.C. just 36 hours before the inauguration. We’re doing four new plays in Ashland this coming season, all written by writers of color and all profoundly grappling with contradictions within our society. And of course the productions of our namesake playwright Shakespeare help us to reflect on the transfer of power, corruption, war, and hope in leadership.

Even the simple act of writing these words was collaborative; many of my kick-ass colleagues on OSF’s senior artistic staff shared their wisdom with me. Theatre is always collaborative. That is the only way we move through this painful moment and come out stronger. We must do it together.

On a final note, I have been thinking so much about the individuals in the rural communities that I worked with through Cornerstone Theater Company, many of whom I know have different political beliefs than I do. Cornerstone’s work has always been about putting a name and a face to and creating a relationship with “the other,” making it impossible to generalize about and demonize other human beings based on any aspect of group identity. I confess that I haven’t always been successful lately, but I’ve been working hard to re-root myself in my love and empathy for my friends in those rural corners of our country (as well as for my own family members whose votes reflect values so different from my own). The work of Cornerstone and other like-minded organizations in building bridges between and within communities has never been more necessary.

Bill Rauch, artistic director, Oregon Shakespeare Festival

Ashland, Ore.

Demand Diversity

To be perfectly honest, my work as a Native American artist hasn’t changed. Unarmed protesters have been under attack in Standing Rock for months and our current administration is not stepping in. This has been status quo for people in this country for generations. So on a personal level, the work simply continues.

That’s what I want for the theatre field as well: Do the work. I see Facebook posts now of new, exciting daily actions people are taking, and that’s great. But I wonder what would happen if we took that kind of daily action to diversify our theatres?Not just the content and cast, but the entire culture of our theatres? What if we focused some of that money and time and social media and calls on demanding the theatre world we all want to see? On building a broader audience for theatre? On throwing out all the rules, making a revolution, and seeing what sticks for the future? Once we do that work, we will be left with a place where all are welcome and represented. That is the place where real conversations can happen. Where the real work can begin.

Larissa FastHorse, playwright

Los Angeles

Gathering and Celebration

The most important thing we can do now is to widen our reach and extend our grasp and broaden the audience. Theatre can effect change, but not when it stays parochial—not when it preaches only to the converted.

Can theatre effect change? Yes, of course. One essential task of our work is in showing ourselves “wherein we are imperfect.” And activist theatre has always been most effective when it has had the broadest audience. So that’s the highest priority: not to become inward, but to redouble and double again our efforts to expand our arms wide, and know that theatre changes people only when they encounter it.

And as much as we need to be agitators against and critics of the way things are, we need as much—more—to celebrate the things that bring people together. We have forgotten how to celebrate because we have lost sight of what to celebrate. And that’s the other essential act we perform: to celebrate how we are different, and how we are alike.

And maybe too to perform as many productions of Arturo Ui as we can.

Gregory Boyd, artistic director, Alley Theatre

Houston

More Temple Than Weapon

Shakespeare understood us. His (and Fletcher’s) Henry VIII is a play about political power and backroom politics, interrupted by occasional political pageantry to appease the common citizen. It carries this extraordinary subtitle: “All Is True.” Of course, if all is true, then also nothing is.

In troubled and troubling times, I believe that theatre has not only an opportunity but the responsibility to portray this confusion and articulate the ambiguities, doubts, and fears of its time. The goal, then, is not to argue a side or a point, but to attempt to portray people and worlds as they are, not as we wish them to be. Theatre, to my mind, is not an argument, but an effort to create and portray human complexity, which we then share with a living audience, at the same time, in the same space: human being to human being.

In this way, as a playwright, I try not to be coopted by arguments and agendas, especially those I may agree with as a citizen. Of course, it is a great temptation, in troubled times, to try and use the theatre as a weapon. My theatre, however, is more temple than weapon—a place to come together, where we perhaps will see ourselves and others, see our world and other worlds, while all the time relishing that we are not alone in our fears and confusions, as we sit together struggling to understand and work things out.

In other words, my theatre is not a place to shout in, or be lectured at, nor where we go to be incited; instead it is a place to come together, sit among strangers in the dark, and recognize the complexity of the world before us. As the great English playwright Harley Granville Barker wrote more than a hundred years ago: “Dramatic art is the working out, in terms of make-believe, of society itself.”

Richard Nelson, playwright

Rhinebeck, N.Y.

Bursting the Bubbles

Ford’s Theatre is the site of perhaps the most destructive act of political violence perpetrated in American history. As a living theatre, we remind artists who work with us that both the playing space and the audience will never let you forget where you are and what happened here. Frequently, these audiences are made up of young people from around the country and families traveling to Washington for the first time. More than in most theatres, many are having their first theatrical experience. Why does all this matter? Because one of the biggest problems we face today, across the country, is that we are not real to one another. It is easy to construct an enemy from those we don’t know.

Both left and right of the aisle, we artists hear that we are “elites” who live in a “bubble.” In some cases, this may be true. Despite globalization, travel, and the Internet, it is easier to live in an echo chamber of those who agree with you.

However, as a national theatre invoking the legacy of Abraham Lincoln, one of our responsibilities is to burst our own Washington bubble and to break the bubble of others. The Ford’s Theatre Oratory Fellows program is one of my greatest sources of hope. This group of teachers represents a broad cross-section of the country, from sea to shining sea and everywhere in between. Aided by continued assistance from D.C.-local teaching artists, these teachers meet twice a year in person and monthly by video conference to share their work integrating theatre teaching strategies into their history and English Language Arts classrooms. In their interactions and their work, by virtually introducing their different students to one another, they demonstrate that the more we get to know one another, the more real we are to one another.

It is incumbent upon us as theatre artists, as teachers and as public historians, to pull back the curtains we draw over people different from us, and those who make us uncomfortable or angry. And it is imperative that we aid others in doing the same. As artists in all of these respects, we draw upon the sense of empathy that makes theatrical experiences transformative. Through playwriting and play-watching, through reading and writing, and through explicitly encouraging our audiences to put themselves in the shoes of others, in the most specific terms, we can develop the muscles of empathy that will save us as a country. By getting to know others onstage and throughout the country, we better our chances of respecting one another even when we disagree. This can lead to greater efforts to learn more and understand better.

So as we struggle with how best to raise our voices against what is wrong with this country, we must remember that the theatre gives us tools to transform people and communities. By bringing together those who may be different, whether in theatrical or educational spaces, we can begin to mend our wounded souls. As the Ghost of Christmas Present implores in Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, “Put down your arms! Put them down! And know me better, man.”

Sarah Jencks, director of education and interpretation, Ford’s Theatre

Washington, D.C.

Why I Woke Up Ready to Fight (a short play)

AT RISE: An empty stage. An ensemble of three or more actors enter the stage.

ALL: Breaking news!

Actor One: Racism is alive and well in America!

ALL: Breaking news!

Actor Two: Bigotry is alive and well in America!

ALL: Breaking news!

Actor Three: Misogyny is alive and well in America!

ALL: Breaking news! Breaking news! Breaking news!

Actor One: Donald J. Trump has been elected president of the United States of America.

ALL: Ten. Nine. Eight. Seven. Six. Five. Four. Three. Two.

Actor One: When Donald J. Trump was running for president—

Actor Two: He said he would force the military to commit war crimes.

Actor One: And here you are talkin’ ’bout, I’m tired.

Actor Three: He proposed to create a database system to track Muslims in the U.S.

Actor One: And here are you talkin’ ’bout, I’m shocked.

Actor Two: He advocated for assassinating terrorists’ families.

Actor One: And here you are passing around safety pins.

Actor Three: He said women should be punished for having abortions.

Actor One: What am I going to do with a safety pin?

Actor Two: He urged supporters to beat up protesters at his rallies.

Actor One: A safety pin won’t mark me safe. Not in Donald Trump’s America.

Actor Three: He made fun of a reporter’s physical disability.

Actor One: It won’t make my life matter. Not in Donald Trump’s America.

Actor Two: He advocated shutting down mosques.

Actor One: I won’t be safe until you do the work you need to do.

Actor Three: He called for a ban on Muslims entering the U.S.

Actor One: Until you face the truth, hold yourself accountable, and learn that there’s room enough for all of us. You see, when Donald Trump was running for president, he said

Actor Two: I could

ALL: Stand

Actor Three: in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot

ALL: Shoot somebody.

Actor Two: And I wouldn’t lose voters.

Actor One: And he was right.

ALL: Ten. Nine. Eight. Seven. Six. Five. Four. Three. Two.

Breaking news! Breaking news! Breaking news!

Actor One: Donald J. Trump has been elected president of the United States of America.

Actor Two: Okay, but what now? What do you tell the people looking to you for answers?

Actor One: Tell them the truth.

ALL: The truth.

Actor Three: We are a nation built on

ALL: Tyranny, genocide, and greed.

Actor One: We call it manifest destiny to justify the lie.

Actor Two: To erase the pain.

Actor Three: To silence those who would dare resist us.

Actor One: And to deny culpability.

Actor Two: We objectify women

ALL: Rape and abuse them.

Actor Three: Deny their rights to their own bodies,

Actor One: And question their sanity.

Actor Two: We dehumanize and demoralize others in order to rule.

Actor Three: Hate is organized.

Actor One: In eight short years, we watched the transformation of white supremacy to white nationalism to the alt-right in order to form a political framework and take a formidable seat at the table.

Actor Two: This was achieved by appealing to and depressing an already aggrieved nation.

Actor Three: Listen, now is the time to act.

ALL: Stronger together

Actor Two: Was more than a campaign slogan.

Actor Three: It was a battle cry, a strategic plan of action.

ALL: A vision for how we move forward.

Actor One: We have to build a ground, ideological, and cyber movement that is rooted in justice, inclusion, intersectionality, and solidarity.

ALL: And we have to start now.

Actor Two: We must be vigilant, clear, and purposeful.

ALL: And we have to start now.

Actor Three: We have to carve out time and space for civic action and engagement.

ALL: And we have to start now.

Actor One: We have to build and mobilize our communities.

ALL: And we have to start now.

Actor Two: We must dismantle white supremacy, bigotry, and misogyny.

ALL: And we have to start now.

Actor Three: We must name these powerful and insidious systems of oppression for what they are.

ALL: And we have to start now.

Actor One: Then, through whatever means we have, we must cultivate empathy, humility, and compassion.

Actor Two: Because as President Obama said—

There is a collective and audible inhale.

ALL: Ten. Nine. Eight. Seven. Six. Five. Four. Three. Two. One.

Actor Three: One voice can change a room.

Actor Two: And if one voice can change a room—

Actor Three: Then it can change a city—

Actor One: And if it can change a city—

Actor Two: It can change a state—

Actor Three: And if it change a state—

Actor One: It can change a nation—

Actor Two: And if it can change a nation—

Actor Three: It can change the world.

ALL: Your voice can change the world!

Actor One: This is how I’m facing today, tomorrow, and all the days I have left on this earth.

ALL: Breaking news! Breaking news! Breaking news!

Actor One: Donald J. Trump has been elected president of the United States of America.

ALL: And we’re ready for him. Are you with us?

End of play.

Jacqueline Lawton, playwright

Chapel Hill, N.C.

Save One, Save a World

On Nov. 7, 2016, I believed in a certain set of values. The outcome of the election held the next day may have buffeted me into bewilderment, but it has not shaken those beliefs. I still want to live in a pluralistic America whose future is always brighter than its past. I still want to bequeath to my children a safe, healthy planet. And I still want to devote my professional and imaginative energies to the beautiful labor of telling stories in the theatre. These values make me who I am, and Nov. 8 has only served to tighten my embrace of them.

It hasn’t been easy. I’ve despaired some, but I’ve noticed that my despair grows in proportion to the time I spend on the Internet, so I’m trying to cut that back. I’ve had surges of optimism, and I’ve noted that my outlook brightens in proportion to the time I spend playing with my kids, so I’m doing that more. What hope I’ve felt—there hasn’t been much—has come when I’ve sat in the theatre. The Old Globe’s annual holiday production is running, and I’ve snuck in to eavesdrop on 600 people as they smile, tear up, and cheer at Dr. Seuss’s How the Grinch Stole Christmas. All of San Diego seems to pass through the Globe at this time of year, a cross section of this wildly diverse region. It’s encouraging to see that for all their divisions, the theatre—live and for real—brings them together as one.

“Globe for All,” our tour of Shakespeare to community-based organizations throughout our county, was playing Measure for Measure in a state prison on Election Day. Cut off from the outside world, the company didn’t learn the results until the steel doors of the outer gate slid open late in the night. The best response to what they heard seemed to them and me to be the very thing we were doing: the rest of the tour. We traveled to neighborhoods whose zip codes are scarce in our ticket and donor databases, visited audiences who look a lot different than the ones we play to in our three theatres in Balboa Park, and brought them live theatre. Eavesdropping on some performances gave me hope. I heard people who’d never seen a play before laugh at jokes written four centuries ago and gasp at the plot’s outrageous turns. I boggled at how topical the play seemed: sexual harassment, injustice, misogyny, abuse of power. I overheard one man in a homeless shelter express disbelief that the play wasn’t written specifically for this President-elect. And once again I saw the theatre make from many, one. In our field we talk a lot about inclusion and equity and enfranchisement and diversity. This work is one way to turn that talk into action.

Most of San Diego voted blue on Nov. 8, but some of the communities we played on tour went solidly red. When I fail to peel myself off the Internet I’m inundated with heartsick cries about how in our liberal echo chamber we’ve lost touch with the half of our fellow citizens who see the world radically differently than we do. We must understand the hopelessness of the Rust Belt, we’re told. We must listen to the ache of those struggling in coal country. I’m sure they’re right; we must. But what “Globe for All” reminds me is that we in the elite coastal corridor of Southern California don’t have to leave our own time zone to find the America outside our bubble. There’s plenty of struggle in our own backyard. The thing is to get there.

I know that the whole thing is not that simple. While I generally feel that there’s no problem in life that can’t be eased a little by having some Shakespeare thrown at it, I’m under no illusions that even the Bard’s mighty powers are a cinch against those of Steve Bannon. Our country’s dysfunctions are severe and big and complex, and I’m cautious about making overly grandiose claims for what we in the theatre and I at the Globe can really achieve. After all, our tour played to 2,000 people around the county, whereas our mainstage season this year played to 200,000. Our engagement work is a fraction of our total impact. And that impact, though large for us, is marginal compared to that of a single 3 a.m. tweet that instantly reaches 20,000,000. We shouldn’t fool ourselves; we’re only a piece of the solution, not the whole thing.

And yet I remember a favorite teaching from the Talmud: “Whoever saves one life, it is considered as if he saved the entire world.” At this moment, the fact that the theatre reaches only a few is something to clutch, not to lament. We’re the regional theatre because our reach is local. That’s our strength. To the lucky few it touches, theatre makes a difference. We know this. This work brings joy, empathy, insight, civility. Theatre matters. The task now is the same as it’s always been: to make it matter to more people.

Our art conjures metaphor. That’s a kind of power. In our buildings and in our neighborhoods we fashion new realities and that creativity can model the America that we wish to live in. We choose the stories we tell and the people who tell them; we can make stories that reflect the country that our votes tried to urge forward on that fateful morning. We can work exponentially harder to get those stories to people who sit not only in our pricey velour seats but also for free in folding chairs in their own community halls, and on the public plazas outside our front doors. We can think about the idea of audience in the broadest, most open-ended terms. We can throw our doors open wider and do everything we can to accelerate change that makes our institutions porous, inclusive, and equitable.

We must do what we do, only more so. We must value what we valued on Nov. 7, only with even more fervor. Save one, save a world.

Barry Edelstein, artistic director, the Old Globe

San Diego, Calif.