Catalyzed in part by the creation of the Kilroys List in 2014, which helped put the catchphrase “gender parity” front and center in the U.S. theatre field, last year we did our own count of who’s writing the plays on our stages, breaking down authors by gender in the 2015-16 season. We also tallied the eras in which plays were written, reasoning that if we corrected for earlier ages in which women’s voices were effectively silenced or shut out, the ratio of female to male authors might look better for plays written more recently.

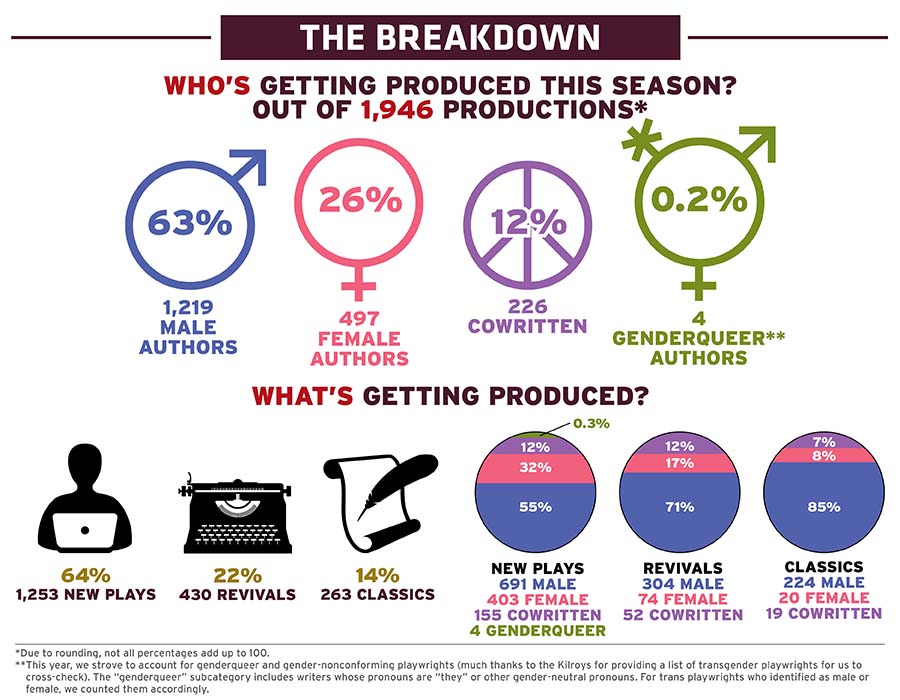

As you can see in the charts below: somewhat. While the male-to-female author ratio overall is 63 to 26 (an improvement, amazingly, over last year’s abysmal 67-to-21 ratio), for new plays it’s 55 to 32. Gender disparity is clearly still a problem, even if the trend line is positive. Perhaps overlooked in these stats: U.S. stages are producing a lot more new works than old, and that seems to us a hopeful sign.

METRICS: To compile our charts we used the same data set as we did for our Top 10 Plays and Top 20 Playwrights lists:

1,946 productions from 411 TCG member theatres scheduled between the dates of Sept. 1, 2016, and Aug. 31, 2017. We defined “production” as anything with at least a week’s run, and we excluded improv shows, readings, cabarets, and festivals.

We counted each production in two categories: gender (male, female, and genderqueer**) and era (new play, revival, classic). We considered plays that premiered between 2005 and now to be “new,” and a “revival” as a show whose first production took place between 1965 and 2004. Anything predating 1964 we’ve considered a canonical work, or a “classic.”

This year we distinguished gender from era in a new way. Any work with more than one credited author, including an adaptor or translator, of different genders was considered “cowritten” in our gender tally. This would apply equally to In the Heights (Lin-Manuel Miranda, Quiara Alegría Hudes) and to Annie Baker’s adaptation of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya.

For the era breakdown, though, in a departure from last year, we did not consider a work like Baker’s Vanya to be a contemporary/classic hybrid. Instead, for the purposes of counting the play’s period, we would call it a classic, straight up—not least because Chekhov’s title is unchanged and his name comes first, signals that while this may be Baker’s “take” on the original it can’t really be counted as a brand-new play. Aaron Posner’s upcoming Life Sucks, on the other hand, would count as a new play; though inspired by Uncle Vanya, the title and credit order tell us it’s Posner’s, and it’s new. (Same with Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’s An Octoroon, and so on.)

We took a similar approach with plays adapted from non-dramatic sources, like films or books (from stage versions of Pride and Prejudice, say, to the innumerable adaptations of A Christmas Carol), and with adaptations of any source into a musical: We considered the debut of the stage version to be the material’s origin date. And, to bring things full circle, in all these cases we considered the genders of adaptors or cowriters, if they were mixed, to make these productions “cowritten.”

A version of this story appears in the October 2016 issue of American Theatre.