Soon after I finished my playwriting MFA at Brooklyn College, a play of mine had a production that caused me more woe than delight. Was this kind of disappointment what my new career would entail? Why had I just spent years on an MFA? In the wake of the show’s closing, I found myself turning over these questions in my mind at the Great Plains Theatre Conference, where my former Brooklyn College teacher Mac Wellman was giving workshops and responding to plays.

One day as we walked from a particularly tasty supper toward an evening performance, I opened up to Wellman about my private doubts. I gave a short speech that concluded with me stammering: “I just don’t know if I want to be a playwright anymore.”

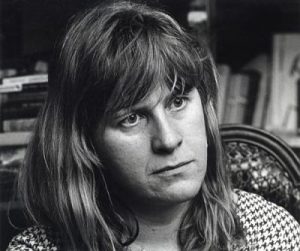

It was twilight, and Wellman was dressed in a black Japanese silk jacket with a lime green Kokopelli pin and a dark denim fisherman’s hat. We were walking slowly—ambling, really. As I began to formulate further remarks, I simultaneously anticipated Wellman interrupting me with a rallying cry to carry on and buck up—with the pep talk I was subconsciously fishing for.

He did neither. Instead he cut me off with something else entirely. In a high-pitched voice, like the kind a kid might use to mock their younger sibling with repetition, he said, “I don’t know if I want to be a playwright anymore!”

It was hilarious. It was also just what I needed to hear.

What is it about Wellman’s uncanny ability to not only say the right thing at the right moment but to say it in exactly the right way—often with wiggled eyebrows and an outlandish accent? Paul Ketchum, a former classmate of mine, describes Wellman’s skill thus: “He knows exactly where to put pressure to release the inner playwriting beast of his students. Mac would hate this, but he’s like a fucking dramaturgical acupressure neuromancer.”

“He has a genius for understanding what individual students need,” says Young Jean Lee, who completed an MFA at Brooklyn College. “He doesn’t try to churn us all through the same meat grinder so that he doesn’t have to think. I’m 100-percent sure that this is the only playwriting program I could have survived.”

“Somehow Mac empowers us to feel like writers instead of imposters,” says current MFA candidate Sarah DeLappe (The Wolves). “I think there’s a certain distillation of voice and artistic ambition that he encourages with super-stealth. And he celebrates stupidity, which is scary and liberating.”

For others, like Jess Barbagallo, Wellman’s wisdom has ripened with time. “Mac gave me advice that I might have dismissed as a student, but its intelligence creeps up over and over again as I get older,” he says. “Mac’s the one who told me I would need to stop performing if I intended to do something with my writing, and I’ve been on a performance sabbatical since February. It’s been some of the most fruitful time in my writing life.”

Wellman’s own writing is wonderfully thorny and difficult to pin down. Erin Courtney, an alum who now co-helms the Brooklyn College program with Wellman, gives it a try: “Wellman’s plays have a linguistic care on the micro level and a Rube Goldberg level of interest in the mechanics of behavior on the macro level.”

Says Lee, “Watching his work is like watching poetry. Nobody cares less about plot than he does. He’s one of the only playwrights I can think of whose work gets wilder as he gets older.” Fellow grad Thomas Bradshaw salutes Wellman’s “complete lack of boundaries regarding form and content. It takes a fiercely bold artist to create new languages the way he has.”

But it’s not like Wellman is simply messing “with form to prove he is virtuosic or so that he can exercise his intellect,” notes Barbagallo. Rather, he says, Wellman’s “spirit and emotion feels tied up in the form-pushing.” Adds current MFA candidate Leah Nanako Winkler, “There doesn’t seem to be a lot of neurosis in his writing, which makes every page seem raw but meticulous at the same time.”

Indeed, says Clare Barron, another MFA candidate, “The entire act of being ‘a playwright’ becomes a creative and revolutionary journey” when Wellman sits at the round table. In addition to sparking the artistic and intellectual pursuits of his students, Barron says, “He teaches us how to navigate this treacherous professional landscape: Make friends with designers, study a foreign language, direct your own work, run your own theatres, don’t accept things the way they are, shake shit up, start feuds.”

Feuds come up often in conversations with current and former Wellman students, though there is scant evidence of any lasting enmity. Perhaps it’s something to do with Wellman’s rascally outlook or his contrarian nature. But a reverence for debate doesn’t diminish the deeper and more profound aspects of his writing or his teaching.

“I return again and again to his koan-like advice on theatre and life,” says Courtney. Speaking of koans, Wellman’s essay “Speculations,” an opus in the making, is a kind of Tractatus à la Wittgenstein that sets forth definitions of theatre to build a ladder toward new methods. Case, and koan, in point:

The structure of a play depends upon where you are in it.

This should be obvious—your experience of an experience depends upon where you are in the experience of experiencing it.

This may seem like madness, but upon further reflection we see that it is not.

We experience theatre moment to moment.

What follows are excerpts from a conversation recorded last May at Café Dada in Park Slope, Brooklyn. He began.

MAC WELLMAN: Should I speak English or Portugesh?

ELIZA BENT: Anglaish! Before we talk about the plays themselves I think it’d be interesting to hear how you came to write plays. You didn’t come out of the womb with a pen in hand.

[Mac makes an alien face and gesture, laughter]

WELLMAN: I was hitchhiking in Holland and I got picked up at a traffic circle in the Hague by a woman in a Deux Chevaux. She said, “If you stay there you’ll get arrested.” It was Annemarie Prins, the first woman to graduate from the Dutch theatre academy. We became friends. She was doing the first productions of Brecht in Holland. Her husband was Beckett’s translator. He knew Beckett and I gave her some poems and they had dialogue in them and she said, “Have you ever thought about writing a play?” I said, “No, I don’t like plays,” because I didn’t. I didn’t like American mainstream theatre.

You were familiar with it?

A little bit of it. But I didn’t like it much. I wrote a few radio plays that her husband translated and those were done on Dutch radio. And then I wrote a very bad play that was staged in Holland.

What was the play?

Fama Combinatoria. It means combinations of things. Actually the idea of the play is great, which is that people are famous because they are famous and that’s the only reason they are famous. I learned a lot from doing that. At that time the Dutch theatre system was great; you could get funds from Amsterdam and the state. They gave us a big chunk of money and I traveled all over the Benelux countries. That started me off.

Annemarie was running a theatre company, Theater Terzijde (Theatre Aside). I saw a Suzuki play there in 1974, ’73, and saw lots of Beckett—all sorts of things. That’s basically how I got started. I remember ranting about how I didn’t like American playwriting and I mentioned Edward Albee and she said, “Oh, he’s different.” She was very interesting and very smart. I remember she was going to a theatre festival in Poland and she learned Polish! I said, “How can you do that?” She said, “You Americans don’t know how to open your mouths.” Which is true.

So all it took was someone repositioning your thinking?

I had studied theatre in college. I read Shakespeare and read all those people for my masters degree, but when I moved to New York after Holland it took 10 years to really learn how to write a play, because I was writing really awful poetic prose.

Tell me about the 10 years of bad plays.

What really helped was meeting Bonnie Marranca and Gautam Dasgupta. They were just starting Performing Arts Journal then, and they made me read a lot of German, Austrian, and European playwrights. Particularly reading Kroetz was very important, because he could write a 20-page poetic play that was realistic but not naturalistic. Gradually I began to try and do things that could be done, but it took 10 years to learn that, because a lot of the theatre that I liked was the early Mabou Mines, Foreman, Wilson, but those aren’t really things that playwrights write.

Those are more company-created pieces.

But I didn’t know that. So it actually took me a long time to write plays I would acknowledge now. My first play in New York was done at American Place Theatre. Bonnie made it happen; she got Carl Weber to direct it, who was Brecht’s stage manager. I remember this guy Wolfgang Roth walked in one day and said, “Charlie, I only work in the shitholes because of you!” And then he spat on the floor. I thought, “Oh, this is gonna be fun!”

But you ignore those early plays?

Yeah, I don’t really like them. I think it takes a while to learn theatre, and you only learn theatre by doing it. It’s not something you can read a book about.

Or go to school for.

No, playwriting you sort of can, because you can read plays. But it’s hard. So I would say as a poet I’m American, but as a playwright my roots are more European, which creates problems.

Why is that?

I dunno. I never wanted to write the American kind of “play.” Some of my plays are disguised—they have five legs instead of four legs. Some of them have tusks.

Oh, I know your plays are multi-limbed!

Careful!

When you say you’re not interested in writing the American play—what does that mean to you?

Ooh, I wouldn’t want to list all the plays that I hate! I mean, I’m not a big fan of Arthur Miller or even Eugene O’Neill, though I think he knew a lot about theatre. O’Neill is a great person but you put him next to Strindberg and he disappears. I don’t particularly care for Tennessee Williams. I think, really, American playwriting began to get interesting in the ’60s with Shepard and Fornes. Before that, it’s screenplays that are great.

I actually think the great period of playwriting is now. The problem is there just aren’t enough theatres willing to do plays. As well you know.

Aye.

In New York everything has to make money and be corporate. So it’s hard. But it continually evolves, so I don’t know where it will be in 10 years.

Looking back at your texts and essays, you never seemed afraid to name names, as in your disinterest in Edward Albee, O’Neill.

I mean, I like Albee. He likes to think he’s like Beckett, but he’s not like Beckett at all. You can’t imitate Beckett but you can imitate Albee and a million people have, and they aren’t as smart or interesting as he is—it’s hard. I mean, that’s why I always try to get my students to read foreign plays. This country is very cut off, I think.

You often encouraged us to let the play reveal itself, or let the structure reveal itself. Will you talk a little bit about that in comparison to the idea of conflict and resolution?

In American theatre, structure is just a set of clichés. Plays are not about plots. They are about moments. And moments are about epiphanies when something happens that wakes you up. But mainstream plays are about reaffirming what the audience thinks it already knows. And I think that’s a waste of time. Why do that? Why not give them a slap in the face? Actually the most interesting playwrights I know are practicing a slap-in-the-face kind of theatre, whether they know it or not. I used to have students write a play with no structure.

How do you ask students to write something with no structure?

I would say, “Write a play that has no structure.” I didn’t explain it. And then they’d write things that were complete structures–they were machines. ’Cause you can’t write something that has no structure. When I started I used to get a lot of people calling me up and saying, “Mr. Wellman, do you teach ‘structure’?” And then I’d do some heavy breathing on the phone and say, “No! I don’t believe it exists!” And usually they would go away and go some place else. But I realized that whole line of thinking is based on the assumption that I know something they don’t know, and they have to pay me lots of money so I can tell them. A lot of people still think that way and that’s completely wrong.

I think you’re a rare teacher in that you eschew guru trappings.

No, I don’t like it at all.

I could tell you weren’t much for sycophants, which was perhaps why I avoided reading more of your plays during school.

I don’t tell student not to read that stuff…

How has your teaching changed over the years?

I didn’t start teaching until I was a member of New Dramatists in the ’80s. I used those New Dramatists classes to develop about four semesters of different exercises, and I’d have a big page in a notebook on whether it worked or not. Alana Greenfield was a student, and Neena Beber—a bunch of pretty smart people. It was interesting and after a couple years I had two years of potential classes, and then I began to get adjunct jobs all over the place and gradually I’d change what worked or what didn’t.

One of the first things I did was to have students write a bad play. Because it takes all the pressure off and they can use their imagination and do something fun. One curious thing I did learn was if I assigned a problem or assignment that didn’t concern me artistically–if I was just being a professor trotting out some set of received ideas–it didn’t work, ’cause I explained it wrong. I thought, “I have to do something that concerns me now in the moment.”

How has teaching influenced your writing, and vice versa?

I like teaching because I see what the younger generation is doing and how it’s becoming different from my generation. But I also like teaching these elective courses, which, as you know, are completely crazy and a lot of fun.

I remember, after having taken a particularly insane elective called “Dictionaries,” I got to see Tim Siragusa perform in one of your asteroid plays out in Omaha at the Great Plains Theatre Conference. I remember thinking, “Of course. This all makes complete sense now,” in terms of the word adventures that play goes on.

The dictionary course was a failure, because people just look at their smart phones now. They don’t go to the library and look at books. I wanted people to use real dictionaries and mess around with the books.

You never assigned that to us!

I tried to… If you use your smart phone to look up words, it emphasizes a kind of willfulness, but when you go to a library and start turning pages then you find words you don’t know. That’s how I wrote all those stories. I’d write a page and then go to the dictionary and ploomph! You find a word that no one understands.

You would write a page and then look for a new word?

I work that way a lot. I get stuck and don’t know where to go. I wrote a lot of them at MacDowell and Yaddo in the last few days of a residency. I’d sneak down to West House and sneak the dictionary up to my room and play with it. And the reason I would do that is because most plays and stories have a very small vocabulary in American writing. And yet the English language has the largest vocabulary of any language that I know of. Why not use that?

And the whole asteroid thing—I found a book with all the named asteroids, and it’s a perfect multicultural thing. If you’re Chinese and discover an asteroid, you give it a Chinese name. If you’re Persian you give it a Persian name. If you’re American you give it a number. So I had a lot of fun. But it took me a long time to write those.

Was the idea or rule that you had to use the next word you found in the dictionary?

No, not always, but I let it inspire me.

I see astronomy in a lot of your plays. Has astronomy always been a passion of yours?

Yeah, I grew up in Ohio and I had a telescope and studied astronomy, and I liked it a lot. Actually a relative of mine built the lens for the Mount Palomar telescope. So I was interested in that. I thought about studying astronomy but I wasn’t that good at mathematics. I have a bunch of plays that are planet plays.

Do you read a lot of science fiction?

I did when I was growing up. I don’t like much of it now, ’cause it’s just melodrama with robots—too much structure.

What’s so bad about melodrama?

Nothing! It’s not what I wanna do. The thing that has really stopped me in my tracks is chorus plays. No one wants to do them because they have too many people. So I’m waiting for someone to do one of them in Yankee Stadium.

How big do you want your choruses to be?

The first one I did, The Invention of Tragedy, had a chorus of 1,000 kids, and Ken Rus Schmoll and I would go around to these schools asking for all their kids and they would send us away! We did a reading at Classic Stage Company and I invited everyone I knew. The chorus started reciting and the floor shook. I thought, “This is great. This is what I want to do.” But it’s hard to do because you can’t get a lot of people in the theatre anymore. Eventually maybe I’ll get lucky and someone will want to do one of these things.

The Offending Gesture had a chorus of five which, which is petite compared to 1,000. Why choral shows?

I like classical music and choruses in classical music. Even when I was in college I was interested in choirs.

Were you ever in one?

Alas, I am not such a good singer. My brother Peter was a good singer, though. I just think it’s something theatre could do that it has not done.

Plus it’s really ancient.

Yeah, and the first tragedy Aeschylus started when one person stepped out of the chorus. Paul Lazar did a workshop of The Invention of Tragedy as part of CSC’s Greek Festival. Jess Barbagallo was in that. So, yeah I don’t know what I’m going to do next. I want to do more operas. But that’s a tricky thing, ’cause it’s expensive. There should be more in New York that’s not Broadway stuff.

In terms of astronomy and chorus stuff, I remember you always encouraged us to maintain our other interests and to not get too wrapped up in theatre to the exclusion of other pleasures.

The theatre world is great but it tends to be shallow and superficial. It’s not sociopathic like the poet world, and that’s good, but it tends to get stuck in a circle. It doesn’t ever go outside of itself, and I think it’s good to do that. All the advances in theatre are people who attack the current state of theatre and say it’s old-fashioned and stupid and want to do something different.

I mean, now theatre in New York is largely a tourist device because there’s no funding for the arts in this country. I think there should be, because it’s an important thing we produce that would help this country abroad as much as oil. But the right wing doesn’t want to invest in the arts and I think it’s a terrible mistake. Therefore, if you do theatre you have to make money. Even things that aren’t going to make money have to look like they’re going to make money.

I talked with my agent today, which I’ll tell you more about after we stop recording.

Good. I know you love gossip.

The best thing that theatre does is create gossip! It’s great gossip—better than anything else.

Do you think gossip has a value?

Yeah. Why don’t people write gossip plays?

Thank you for giving me the idea to my next spettacolo! I want to talk about constraints. What do they mean for you, and why are constraints important in writing?

A constraint enables you to create something that will have a shape that reflects something that you are interested in without imposing an abstract structure on it. In that way it does resemble poetry—current poetry is all about constraints. Rather than traditional forms, it’s about constraints.

But I also wish more playwrights would write criticism. Everyone complains about the critics but then they don’t attempt to provide any source of information about the debate.

It seems a lot of editors aren’t open to artists writing about theatre because they’re scared there’s a “conflict of interest.”

I think that’s wrong. German theatre and English theatre are at their strongest when playwrights run theatres and playwrights voice their opinions and actually argue. It’s good to argue. If you have an establishment that just says, “This is good, that’s bad,” that gets tired quickly. I wouldn’t mind arguing with someone who really loves Tennessee Williams.

Why should more playwrights be in charge of institutions?

Because institutions are more interesting that way. Directors—I know a lot of good directors—but as directors get older their taste gets more conservative. One of my friends, he was starting out as a director, he directed Franz Kroetz and all these experimental things, and now he’s directing Driving Miss Daisy in Australia. I’ve seen it year after year, what happens to directors. They get afraid of the audience.

Why?

Directors are very competitive with each other. They don’t like other directors, and when they see a director gets a good Times review for doing a play, then they do the same play. Playwrights and writers actually like each other. They are supportive, and even if they’re competitive, they’re not out to destroy each other. Directors, particularly when they age, they get very conservative and snarky and want everything for themselves. I also think playwrights should direct more.

This leads us into another thread from your essay Theatre of Good Intentions, which posits that a lot of institutions exist to help the playwright and support the playwright, which you describe as “treating the writer like a half idiot child.”

Yeah, a lot of that money that goes to these institutions. I think they should give it directly to playwrights; also give it to directors and actors. That would mean federal support of the arts.

Would you take money from Donald Drumpf?

Of course I would. I have a dummy letter to him to that I wrote when I was working on tuition abatement for all CUNY MFAs. The letter explains how it would cost $23 million to support all the MFAs in writing for 10 years. I never sent it because we were trying to get a CUNY-wide system in place and it hasn’t happened yet. I think there should be federal support for the arts.

You don’t think there’s a danger in censorship?

No, censorship is what destroyed federal funding—Jesse Helms and people like that. Cuomo’s father in the late ’80s. In three years Mario Cuomo cut the budget in half. I got appointed to the state board of the arts.

You did?

I’ll explain why. There was a theatre company called Shaliko and they applied for a NYSCA grant for me. It was a low point in my career. Nothing was happening. I thought, “Why waste my time on this shit? I’m never gonna get it.” The artistic director kept bugging me to send stuff for the application—like, a plot. I said, “Fine, you want a plot? I’ll give you a plot.” It was for a play called Weasel Shit. All the characters had long Hungarian names and it was about one man who tries to bribe another man’s girlfriend into fucking a snake for a bucket of weasel shit. I spelled it out, “Bum, bum, bum, this happens in this scene,” and thought: That’ll take care of that.

And?

Six months later the artistic director called me up and said, “We got the grant for Weasel Shit.” I was walking down the street and somebody yelled at me, “How’s Weasel Shit coming?” I tried to figure out why I got the grant. It was the biggest grant NYSCA had ever given out, because after that Cuomo started cutting the money. It was because I said what I would do. There was nothing in it that appeased or talked about uplifting social stuff, and that appealed to a lot of people. And then when I got on the NYSCA panel I read a lot of applications and they were all identical: socially uplifting, positive, vague applications. I didn’t write Weasel Shit; I wrote another play instead, Whirligig.

Will you ever write Weasel Shit?

Maybe.

So why do you think there’s this desire to describe things as socially conscious, uplifting things that involve community engagement?

I think it’s a way of being political that’s acceptable here. The problem is that it’s easily coopted by the powers that be.

You mean institutional theatre?

Yeah. So again, it’s hard to avoid writing things that are obvious and not very challenging or actually not very interesting. So it’s better to just write something that comes into your head randomly rather than something that’s socially uplifting. I think. And there’s an enormous amount of censorship in the theatre anyway.

Describe.

Well, there’s certain things you can say and certain things you can’t say. I won’t say which is which because it’s obvious. Theatre is very cautious and very conservative. It’s always following current events but a little bit behind. That’s why I’m interested in people like the Futurists. Marinetti attacked Italian museums, he attacked pasta. There’s still a Futurist restaurant in Milan that serves not pasta but raw liver with melon!

Ma che schiffo! Weren’t those dudes kind of Fascists?

Well, Marinetti was. But he’s more complicated than that. The Russian Futurists are interesting group too—the Oberiu crowd. Theatre can do that stuff very well, but it doesn’t very often because it’s too scary.

Is this part of why there’s a big push to writers at Brooklyn College to do it themselves?

No, I just think you should all be starting your own theatres together, if you possibly can. Like 13P and Joyce Cho and Chochiqq. Now Sibyl Kempson has her own company. Tina Satter does too. Young Jean Lee. There’s a whole subculture and they influence each other. And none of them are giving a moral lecture so much as trying to wake up the audience. But it’s hard to do that.

You also encouraged us to create our own ways of talking about theatre and to make our own vocabulary for talking about plays.

I did that in Crestemathy a little bit. And I took another stab at that in Speculations.

Ah, the famous Speculations.

Read about 20 pages of it and then put it down and have a glass of rosé. Mention Speculations in the article and tell everyone they should read it. It’s my masterpiece! It’s in progress. I’m very skeptical of the Internet but it’s now about 100 pages. I’ve had fun with that.

I just think theatre’s always evolving, and because times change theatre shouldn’t get nailed down by academics and corporate businesspeople and boards of directors. But that happens so easily. And very well-meaning people get coopted by people with money.

Omaha is interesting because it’s Warren Buffett town, but there’s a lot of interesting theatre there because it’s not corporate. And I suspect there’s a lot of interesting theatre all over the country but it escapes the general media. I grew up Cleveland and the Cleveland Play House did the first Ibsen plays in this country before New York! Cleveland also had the first really important black theatre companies and the Cleveland Orchestra was important—still is. I don’t know if there are interesting theatres there now. Probably there are. Next spring I’ll be in Cleveland for the Mac Wellman Homecoming festival.

I was interested in something you said at the beginning of our conversation regarding a distinction between naturalism and realism.

Well, naturalism in this country tends to get sentimentalized. It’s not about what people actually say and do, which is interesting; it’s about their motivation, their sensitive inner lives, their conflicts because of their bad childhood and their addictions and all of that kind of baloney. Rather than the weird things you see people do every day.

One of my favorite things was: I was in a restaurant, I looked out the window and a car pulled up at stop light and the guy was brushing his teeth. Why is that in no play? I used to write those things down—what people say is incredible.

I remember seeing people carry a dead shark into a bank.

Stop.

A 10-foot-long shark. They were having a lot of trouble getting it to fit into a revolving door.

No! Where did you see the shark in the bank?

That was in the East Side. I don’t know what they were doing with it.

How did you know it was a shark?

It was a dead shark!

Was it wrapped?

No.

How were they carrying it?

On their shoulders.

This is real?

When you walk out the door of this café before you get to 10th Street, you’ll see half a dozen things that are deeply real that you’d never see on the American stage because they don’t reflect the sensible and wonderful psychology of the American middle class.

Playwright/performer Eliza Bent is a former senior editor of this magazine.

A version of this story appears in the October 2016 issue of American Theatre.