John McMartin—herein referred to as Jack—was one of my closest friends for more than 50 years. Our friendship extended to Charlotte Moore, his partner for more than 40 years, to his daughters Susan and Kathleen, and to my family, my wife Judy and our “kids” Daisy and Charley. We were each other’s extended families, sharing times in Majorca, in France—all over the world, really. Choice times they were.

Soon after we met, Jack dubbed himself “The Humiliated Guy” and I became “The Embarrassed Guy,” and those appellations stuck.

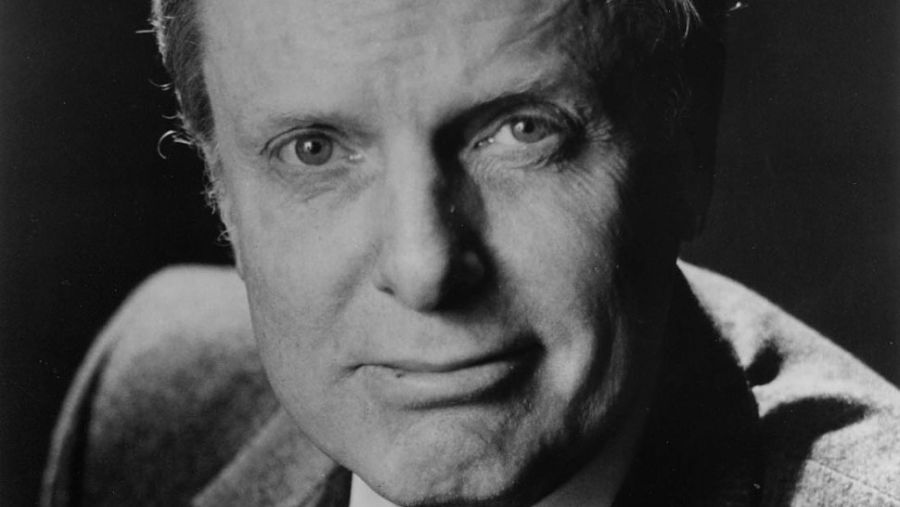

Jack made a sensational pal. A great actor—he was capable of a range of epic performances. Whether he was a claustrophobic, buttoned-down accountant trapped in an elevator with Gwen Verdon onstage in Sweet Charity or on screen with Shirley MacLaine, he was endlessly inventive.

Jack was a secret fellow. You had to pull information out of him. He absorbed. And he chose to suffer in silence.

But on the stage—well, on the stage he found his wings, whether playing a nutty sorcerer in Love for Love, toothless with a rope of clanking skulls around his neck, or a tortured young Eugene O’Neill in his autobiographical The Great God Brown.

Rarely was he cast close to type. Recently he played a Senator in All the Way. Jack looked like a Senator, albeit a handsome and intelligent one; or on film an editor in the magnificent All the President’s Men.

Jack always worked. So a list of his roles is too much for this appreciation, as would be the list of the awards he won and his countless Tony nominations. And he made it to the Theatre Hall of Fame.

Stephen Sondheim has said that Jack’s performance in Follies was one of the greatest stage performances of our time. In the final moments of that musical, Ben Stone, its flawed hero, sang “Live, Laugh, Love,” a jaunty paean to the joys of life, surrounded by a chorus of beautiful Ziegfeld dancers. Halfway through the number, Jack/Ben hesitated—apparently a momentary glitch; seeking a lyric, finding it, and recovering, he went on, only to be stopped dead. Seeming to have forgotten the lyrics, then recovering them, he stammered on. Found them, lost them, while the girls on either side of him kept tapping away. He grabbed frantically at his head. The audience at the Winter Garden Theatre grew restless, looked at one another, then, visibly sinking in embarrassment in their seats, they buzzed until Jack let go with a cry of bewildered pain. We were witnessing a nervous breakdown. Now the audience understood it: It was part of the show. Ben Stone was cracking up. Not John McMartin—Ben Stone. You should’ve been there.

Years later I structured a new adaptation of the Kern/Hammerstein masterpiece Show Boat. In my adaptation, the burden of the show’s pulse, its forward motion, was the responsibility of Cap’n Andy, played by Jack. When he wasn’t onstage motivating the action, he was backstage aging—wigs, facial air, a paunch. I spent an evening trailing his offstage activity, and he never for a second stopped to replenish. He carried the show on his shoulders and he never mentioned that to its director.

You probably wonder why I titled this piece “Chien Domestique, Elephant Sauvage.” Well, that represents Jack’s entire French vocabulary. They popped up unexpectedly of course in France, but also when there were gaps in conversations. Abruptly he would fill a void with those four French words. Where did they come from? I tried to find their source, but I haven’t a clue. If anyone reading this would enlighten me, I would be forever grateful.

I could go on and on about Jack. Because I know he is not gone—he’s still here, and wherever he is, I know he’s shrinking in mortification by this love letter. Which this Embarrassed Guy intends it to be.