NEW HAVEN, CONN.: There was $440 in cold cash just sitting on the large wooden table in the middle of an oak-paneled room at a private club in downtown New Haven. Twenty audience members sat around the table and were asked to unanimously decide how to spend the dough during an afternoon performance of The Money. Easy enough, right? Think again.

This conundrum was not the only mental exercise given to audiences at the New Haven International Festival of Arts and Ideas, which took place June 10-24. True to its name, the festival boasted a menu of mind-stretching theatre, as well as music and dance performances and expert panels.

The six theatre pieces included esoteric works that deconstructed myths and classics; a circus-infused, kid-friendly show; a performance as intimate and startling as reading a book aloud in a hushed library; and a Fringe hit bound for the West End. And then there was that immersive money piece where the audience was the show.

The big-ticket item of the festival was Our Ladies of Perpetual Succour, from the National Theatre of Scotland and Live Theatre in Newcastle. The hit from the Edinburgh Festival Fringe made its U.S. debut as a warmup to its U.K. tour and London run.

The musical play could be subtitled “Catholic School Girls Gone Wild,” as it follows six untethered teens making their way from the confines of their rural Scottish village to a national choir competition in Edinburgh. Though their voices are angelic (the cast’s rendition of Mendelssohn’s “Lift Thine Eyes” is heavenly), they’re rebellious devils, having carefully plotted their great escape into sex, drink, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll. Don’t let the plaid pleats fool you. Accompanied by a three-piece combo, the girls shift at the drop of a halo from Handel to Hendrix.

Adapted by Lee Hall—who wrote both the film and stage versions of Billy Elliot—from Alan Warner’s novel The Sopranos, the show was staged with fierce, unrelenting energy by Vicky Featherstone, NTS’s artistic director. But this coming-of-age tale is no simple, exuberant depiction of girl power but a darker tale of class, repression, and unfulfilled possibilities.

At times, the endless crude talk becomes tiresome and the melodrama predictable; a lot of early narrative exposition gets lost in the thicket of slang and brogues. But there’s something ballsy about the cumulative cockiness of these wayward ladies—the entire cast is terrific—that makes you root for them, especially in light of their limited lives.

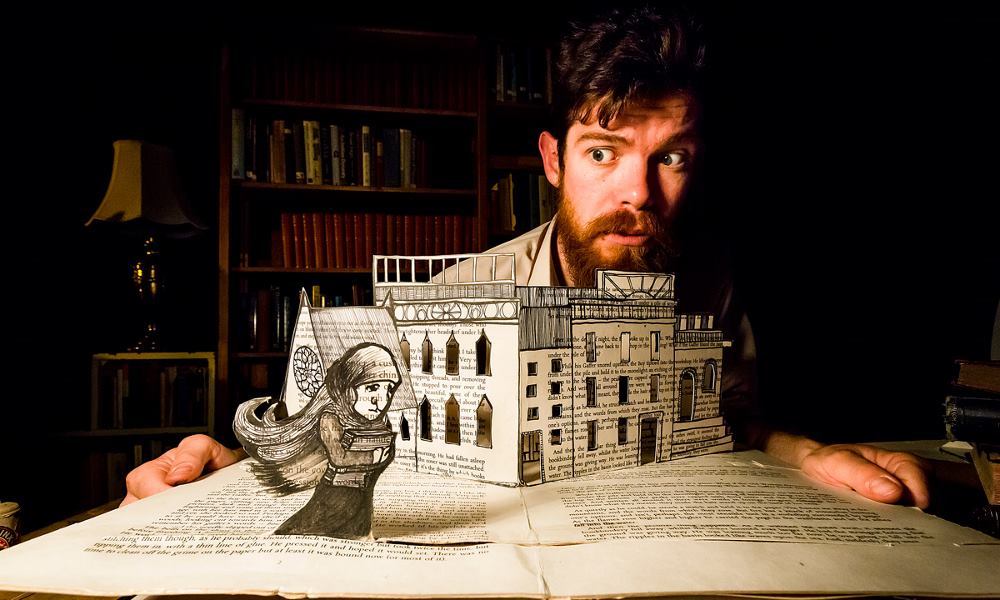

The Bookbinder, written and performed by Ralph McCubbin Howell of New Zealand’s Trick of the Light theatre company, though also in its American debut, is the theatrical opposite of Succour. A quiet, intimate solo show inspired by the works of Chris Van Allsburg and Neil Gaiman, the piece begins with Howell asleep at a library table as he wakes up to tell his prospective “apprentice” (the audience) a tale about his dangerous craft, using shadow play, puppetry, and pop-up books. It’s a spellbinding story that is distinctive in its modesty and compelling in its narrative.

Around the corner, the two-member cast of the New York-based Acrobuffos performed Air Play at the Yale University Theater. In this one-hour, kid-friendly piece, Zen philosophy meets chaos theory. The story follows a brother and sister on an epic journey within a circus-like environment where a circle of a dozen large fans propel various objects—balloons, fabric, glitter—around the room. The piece features audience participation and clever balloon manipulations, such as a stunt where the almost silent clowns magically transform into one of their inflated creations. But it is the elegance of the long bolts of translucent cloth, the luminous balls floating like atoms and the fistfuls of swirling glitter, that make for a theatrical treat satisfying as both a contemplative experience and as a joyful one.

In addition to playfulness, deconstruction was a central theme of the festival. SITI Company’s minimalist song-and-dance treatment of the John Henry folk tale, Steel Hammer, explored this idea. Directed by Anne Bogart, the show originally premiered at the 2014 Humana Festival of New American Plays and continues to tour. The New Haven stop featured a six-person ensemble led by Eric Berryman as John Henry, six musicians from the Bang on a Can All-Stars ensemble, and a trio of female vocalists. Kia Corthron, Will Power, Carl Hancock Rux, and Regina Taylor wrote the scenes, and Pulitzer-winning composer Julia Wolfe wrote the music.

The Square Root of Three Sisters also provided an new take on a well-known story. The production was a world premiere collaboration with the Yale School of Drama, Yale Theater Studies programs, and Russian director Dmitry Krymov, in his first English-language production. The image-rich show is based on Chekhov’s Three Sisters, as seen by a theatre troupe attempting to put on a production, with a dash of The Seagull and The Cherry Orchard thrown in for good measure.

In the first half of the show, the actors play themselves as they prepare the performance space for the show, engaging in almost playground-like antics as they define the worlds of the plays. In the second half, the actors then play actors playing Chekhov’s characters, but in “essential” ways, letting the physical environment inform and distill their states of distress, depression, and anxiety in their pursuit of happiness and love.

The final theatre offering of the festival was The Money, an interactive performance piece by the British company Kaleider, in which a group of audience members chooses to become “benefactors” while the rest become “silent witnesses” and observe. During the performance I attended, the central argument was about which charity would be the benefactor of the $440 laid out on the table. And this was not just an intellectual exercise—the money would actually be doled out if the group reached an agreement before the digital clock ran out. If no decision was made, the cash would be used in the following performance. As the debate wore on, it was clear that a sense of community and consensus can be a fickle thing.

Although the theatrical offerings at the Festival of Arts and Ideas broke some boundaries—traditional narrative (Square Root of Three Sisters), the fourth wall (The Money), disciplines (The Bookbinder), even social mores (Our Ladies of Perpetual Succour)—all were connected by a sense of ritual. Whether it was the exhaustive circling of the performers in one memorable moment in Steel Hammer, the craftsman-like methodology of a bookbinder, the precise placement of an electric fan, or the rules we must follow to make a buck, it is ritual that gives us the power to comfort, confine, and confront.

Frank Rizzo lives in New Haven and New York and writes on theatre for Variety, The Hartford Courant, The New York Times, Connecticut magazine and other publications.