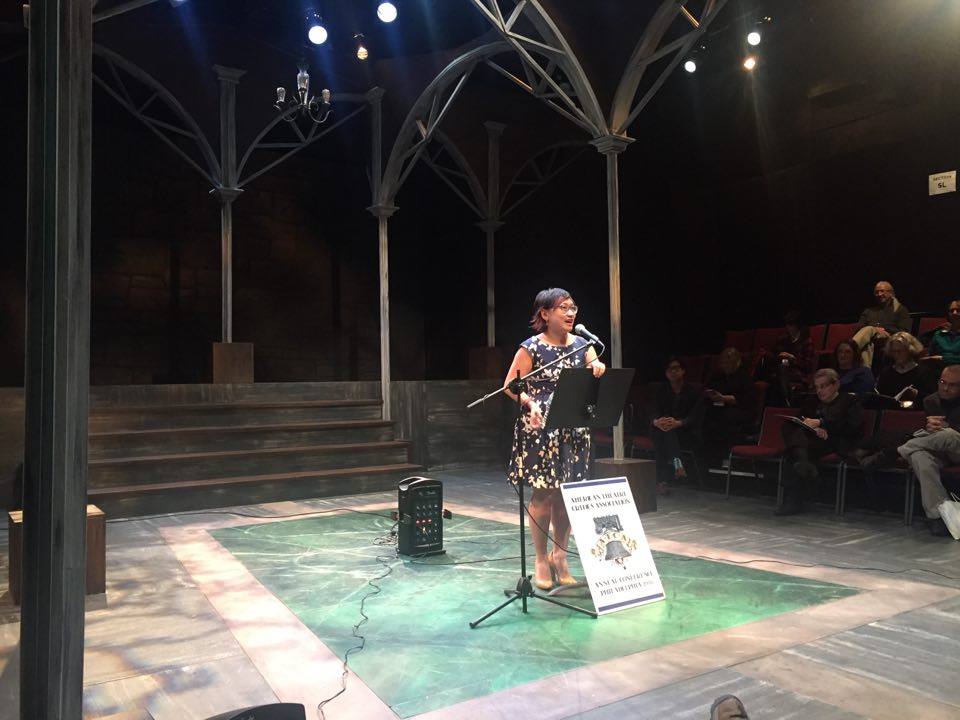

Billed as the keynote speech to the American Theatre Critics Association conference in Philadelphia April 6–10, this talk by American Theatre‘s associate editor is also the latest in ATCA’s Perspectives in Criticism series, which goes back to 1992, with a roster that includes Frank Rich, Margo Jefferson, Robert Brustein, and Terry Teachout. The speech is also published here.

Thank you all. I feel incredibly honored to be standing here at my first ATCA conference, and to be asked to address you as an equal, even though, judging from the rosters and résumés of the speakers who have come before me, including my former boss, American Theatre founder Jim O’Quinn, I am the youngest person to have stepped into this podium by far.

The way I was brought up, in a semi-traditional Vietnamese family, you don’t talk back to your elders, and you especially don’t tell them what to do. So this is surreal for me! And I have to admit, I’m feeling very nervous standing up here, talking to all of you, who have probably been in this field longer than I have been alive. I am a 27-year-old millennial and have only been a journalist for 5 years. And I don’t review shows. What can I tell you that you don’t already know?

But no problem—I will be fine, I will not run from this podium, and hopefully we will all come out of the other side of this speech intact.

When Bill [Hirschman] first asked me to come here and to speak to you about the future of arts journalism and diversity, I said to him, “You know this isn’t going to be a positive speech, right?” I am going to tell you what this speech is not going to be. It’s not going to be about the virtues of criticism. And it won’t be a speech on how to become a theatre critic. I’m not a critic, and I’m still not entirely sure how you become a critic! To me it seems like a matter of throwing salt over your shoulder and giving an editor your firstborn.

For this speech, I’m going to be what those my age call “real.” I’m going to be realistic and honest. And I hope that based on my experience, you can glean some pearls of wisdom.

Part 1: A little bit about me

I was born in Vietnam. In a city caled Da Lat. It’s located on a hill and the French penetration was so strong during the early 20th century that there’s a replica of the Eiffel Tower in the center of town. My dad fought in the Vietnam War; we were on the South Vietnamese side. In 1990, my family immigrated to the United States when I was 2 years old.

Being raised in Anaheim, California, just a short drive from South Coast Repertory, I never saw any theatre. In fact, when I was young, the idea of theatre felt embarrassing to me; I hated public speaking. A person going onstage, in front of a crowd, reading lines written by people who were dead, in English that sounded so formal and unlike the English I used to speak to my friends…I remember one of the first times I saw Sound of Music, and as the helicopter flew around Julie Andrews and she cried out, “The hills are alive!” it was so silly that it made me laugh. I didn’t think about Rodgers and Hammerstein again until college.

To an immigrant kid who grew up in a two-bedroom apartment where I had to share a bed with my three older sisters (side note: It was actually two twin beds that my parents smushed together to make one large bed), The Sound of Music seemed far away, elitist and unrealistic. And even though my dad had a college education and had read Shakespeare, my parents couldn’t afford to buy me Barbie dolls, let alone take my sisters and me to live theatre.

I didn’t see my first live production until I was 14, when my older sister took me to the Broadway tour of The Lion King. We all need a gateway drug. Then I discovered Sondheim and Sarah Kane in college. That was when my obsession for dark, sad, gruesome, and weird theatre started. And it hasn’t stopped.

I guess the moral of the story is: If you know a kid who dislikes Rodgers and Hammerstein and therefore all musicals, make them listen to Sondheim.

Part 2: How I became a journalist

I think everyone here has a variation on the same story, which goes something like this: I never planned on writing about theatre for a living, but surprise, surprise! Here I am now.

I’m guessing the next question is: How does an immigrant who didn’t grow up watching theatre become a theatre journalist?

Well, first, you have to love writing, which I did. When I was a kid, I would write and illustrate my own books, and then bind them together using a hole punch and strings. I was going to be a fiction writer when I grew up.

So I did my undergrad at the University of California, Los Angeles (go Bruins!). That was when I realized that artistic careers rarely made money. Because I was short on book ideas but high on SAT vocabulary words, I decided that the only way I would be paid for my writing was to be a journalist.

This was 2007, by the way, just before the industry crashed. I had a great sense of timing.

I actually have a theory that journalists, especially critics, were the kids who would rather play alone than interact with other people. (Or maybe that’s just me.) Being an outsider is great if you’re a journalist, because you have this creepy skill of looking at strangers and analyzing their behavior.

My second year at UCLA, I joined the Daily Bruin, the student newspaper. I wrote for the arts and entertainment section, because I was an English and art history major. As you can see, I was really intent on not becoming a doctor, lawyer, or any other kind of Asian stereotype.

Then my editors assigned me more and more theatre reviews and features. Side note: Those editors included Suzy Evans, who now works with me at American Theatre. So my career is partially her fault.

Anyway, somewhere between interviewing Rajiv Joseph about Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo and reviewing Danai Gurira’s Eclipsed, I realized this: Writing about live theatre is fun! Being exposed to artists and their passion for their work, that passion was contagious. Really, isn’t that why we all spend an inordinate amount of time with theatre artists? Because watching them do the work and talk about it is hypnotic. And saves us the pain of having to do it ourselves. After all, those who can’t do…become journalists.

But most of all, for me, plays like Bengal Tiger and Eclipsed—these were modern plays that spoke about our modern world in a very relatable and visceral way. They spoke profoundly to my experience as a young woman of color whose parents survived a civil war. And those plays were in a language I didn’t have to struggle to understand. No offense to Shakespeare.

I related to Rajiv and Danai’s plays. And it made me want to find more plays like that, and to advocate for work like that: work that takes a story we have never seen, of a people rarely represented, and make it live onstage. That is the kind of theatre I want to see, and the kind of theatre that is inclusive and welcoming to all different stripes of people, and all different kinds of stories. But I digress.

So my junior year, I asked my journalism adviser what I should do: Should I try to send out my résumé or should I go to journalism school? Besides going to JournalismJobs.com and sending out your résumé blindly, how do you get hired? She suggested grad school, because that’s where you could get connections, which is how you break into the industry. And she was right. Because as soon as I graduated from the one-year Goldring Arts Journalism Program at Syracuse University, an alumni emailed us saying that American Theatre was looking for an editorial assistant.

Now, almost five years later: Here I am, an associate editor, speaking to you.

Part 3: Microaggressions, or racism in a minor key

Last year I wrote an essay called “4 Ways Theatre Critics Can Be a Little Bit Less Racist.” It was in response to a disturbing trend I was noticing, which is that theatre critics tend to write very problematic things when they’re reviewing plays by playwrights of color or plays that have non-white characters. And these are critics that I looked up to and respected: Chris Jones, Charles Isherwood, Charles McNulty, Hedy Weiss.

I have since realized that I do some of my best writing when I’m angry. And the spark of anger that led to that essay was lit by Jeffrey Gantz of the Boston Globe. In his review of A. Rey Pamatmat’s Edith Can Shoot Things and Hit Them, Jeffrey wondered why the Filipino-American characters never talked about being Filipino. He wrote, as a criticism of the play: “I wish more of their culture were on display, and it seems odd that they have no racial problems at school.”

That line sparked a very specific rage in me. I grew up in a school district that contained Latino, white, and Asian students. And I was never bullied by my peers for being Asian. My life, and the life of many people of color that I know, isn’t a 24/7 grand display of, “Look how ethnic we are!”

Assumptions can be dangerous and hurtful. Once on the streets of New York, an older man, he might have been in his 60s, came up to me and said, “You’re so beautiful, but you Chinese people should go back to where you came from.” He got my ethnicity wrong, but hey—at least he thought I was pretty?

Jeffrey Gantz’s review wasn’t a personal attack on me, or on A. Rey, but it felt like it.

So, while at the Critic’s Institute at the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center, I wrote a piece called “4 Ways Theatre Critics Can Be a Little Bit Less Racist.” In it, I posited four points that all critics should consider when reviewing works by playwrights of color. They were:

Point 1: Don’t ask the playwright of color questions that you would not ask a white playwright.

Point 2: Avoid stereotypical adjectives when describing different ethnicities.

Point 3: Call out problematic representations when you see them.

Point 4: Own your mistakes.

You can read the entire article on AmericanTheatre.org. It was one of the most clicked pieces we ran last year. But this problem isn’t letting up. In fact, it keeps on happening with increasing frequency.

Last month, the Latino Theater Commons released a piece on HowlRound called “Cultural Microaggressions in Theatre Reviews.” It was inspired by a New York Times review of Ropes by Barbara Colio at Two River Theater, about three brothers whose father abandoned them. In that review, critic Michael Sommers wrote: “It is curious that Ropes…possesses no Latino flavor or content.”

I’m not sure what he meant by “Latino flavor.” Did he want accents, a mariachi band, more hot sauce? Did everything I just say sound vaguely racist to you?

In response, the Latino Theater Commons wrote: “We ask that reviewers watch our plays without expectations about what a Latina/o play should be. To call for a Latina/o play to have more ‘Latino flavor’ is an act of exoticization. Latina/os are not exotic. We are not a flavor. We are human beings. We are Americans.”

We are at a turning point as arts journalists. The work we’re writing about is so diverse, written and starring people from all kinds of backgrounds: East Asian, Indian, Latino, African-American, Caribbean-American. And that’s just the stuff going on along 42nd Street in Manhattan. Not to mention the different forms that theatre is taking: realistic dramas, hip-hop musicals, dance theatre, immersive theatre, experimental theatre. One of the best things I’ve seen recently was billed as a rock fairy tale that was part concert, part religious ritual.

Unfortunately, while the work is varied, the demographic of the people writing about it is not. The theatre criticism field, and the overall journalism field, is overwhelmingly white and male. I can probably count on my two hands the number of working, full-time female critics. As for critics of color?

Well, there is a reason you asked me here today.

It’s because our working critics, the ones working at the most respected publications in the country, are advocating for the racial profiling of Muslims, or categorizing a Tanya Saracho play and a Karen Zacarias play as a “telenovela,” or using food analogies such as “jasmine rice” and “kumquats” when talking about a play by Nandita Shenoy. Why do critics write this way about works by playwrights of color?

From what I see, the problem is two-fold.

1. A majority of the critics with full-time jobs have been at their post for more than 20 years. And in that time, the way we talk about race in America has changed significantly. So the way that critics address race in their reviews must also change.

2. There is a substantial lack of critics of color working today. Because of that, the critical conversation is unfortunately one-sided.

Part 4: The way we write now

When I wrote “4 Ways,” the thing I most wanted critics to understand was that we all have unconscious bias when we review plays. If Charles Isherwood can admit that he hates Adam Rapp plays and stop reviewing them, why can’t more critics admit that when they see a play featuring an ethnic character, they have a set of assumptions about what that character should do? And that set of assumptions may be different than the assumptions they have about a white character?

Why is it, in the reviews for the play This Is Modern Art by Idris Goodwin and Kevin Coval, the group of young black men engaging in graffiti art were called “urban terrorists”? Meanwhile, I haven’t read a single review that calls the white kids in Rent squatters; after all, they sing a song about not paying their rent. Both shows advocate for the same thing: the breaking of societal rules in the name of self-expression. But for some reason, when black kids do it, they are terrorists.

Last year, I watched a YouTube video called the Doll Test, posted in 2012. In it, a group of children, around 6 or 7 years old, were given two dolls: a black doll and a white doll. And they were asked a number of questions, including: Which doll is good? Which doll is bad? Which doll is beautiful?

Can you guess what the answers were?

Most of them, even the black children, saw the white doll as beautiful and good, and the black doll as ugly and bad.

In the year of the #OscarsSoWhite campaign, it goes without saying that we are currently in a society that views the white experience as the default experience. The result is that a majority of our entertainment is created by white artists, produced by white executives, and feature white characters.

It means that we have all been socialized to read the white experience as the universal one, as the one we should identify with and have empathy for.

So what happens when you see a play like A. Rey Pamatmat’s Edith Can Shoot Things and Hit Them, and see a character that is Filipino? Because a majority of the plays that you see feature white characters, this Filipino character stands out, and you want to learn more about them, about their background.

There’s no harm in wanting to know more about this character’s Filipino roots, right?

Right, except when the play is not about race. It’s the difference between Flower Drum Song and the all-black production of A Streetcar Named Desire on Broadway—a show about race and assimilation versus a show that just happens to feature black people in it. To quote myself: “Don’t make plays that are not about race about race just because the faces on the stage are non-white.”

After all, why must a non-white character have a reason for why they’re not white? And why must the inclusion of a non-white cast include, in the reviews, racialized language such as telenovela and jasmine rice? Why are white characters given unconditional empathy while characters of color have to prove themselves and earn it? I’m not saying critics aren’t allowed to dislike works by Latino writers, or any writer of color. But perhaps when you’re writing about why you didn’t like it, don’t say it was because there wasn’t enough ethnic “spice” or “flavor” in it. It makes you sound racist.

Because that language is othering. It reduces people of color to a bag of racial signifiers and stereotypes. It denies us our multifaceted humanity. It also sends a message: You are not white, therefore you need a reason to be here, because this art form is not meant for people like you. So we are going to compare you to food, we are going to wonder why you’re not “ethnic” enough. Because that’s the only we can talk about about people like you.

To which I say: do better. Use your words.

In an industry where white is still the unfortunate default on stage and off, critics should not be contributing to this antagonizing culture. The theatre field is striving for diversity. The journalism field is striving for diversity. Is this the message we want to send to today’s young people of color: that they are outsiders in a profession for white people?

I believe that we should never stop growing as journalists. When I was 19, I wanted to be a writer. Now, almost 10 years later, I’ve created a podcast, created the American Theatre website, and have incorporated criticism into my work. And I see many critics here who have navigated this changing media landscape with grace. You’ve learned how to use multimedia and social networks. Some of you are even on Instagram!

If we can do that, then every person in this room, and anyone who’s listening to this online, can reevaluate the way they write and what they write, especially when it comes to work by or featuring people of color. So the next time you or a fellow critic writes something that readers find racially offensive, don’t dismiss the accusation. Talk to the people making that assertion, hear why they have an issue with it. Learn the why and the how. We can never really know what the person sitting across from us is thinking. But at the very least, we can try to understand.

After all, the reason all of us do this job is because we have empathy; we want to crawl into the brains of artists and discover their secrets and process.

Theatre Communications Group, the publisher of American Theatre, now has an in-house Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion committee. And our entire staff was taught about concepts such as microaggression, institutionalized racism, and the difference between cisgender and transgender. Today’s publications would benefit from such training. Heck, the Washington Post and American Theatre have started using “they” as a gender-neutral pronoun! Because as our readership diversifies, we need to change how we address them.

We can even make Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion a session at the next ATCA conference. Just an idea.

Being flexible is how we stay relevant.

It’s not about being politically correct, it’s about being inclusive. Our writing and our platform has the ability to foster change, but it can also propagate damaging stereotypes. It’s up to us to choose what we want our voices to do.

For me, I choose change. I hope you do too.

Part 5: How do we foster new talent?

I want to preface what I’m about to say with this: The things I am saying do not reflect what every journalist of color has faced. I can only speak for my experience and what I’ve observed.

I saw a play last year at South Coast Repertory called Vietgone by Qui Nguyen. It was about the aftermath of the Vietnam War, and it hit me so hard. In the way that happens when you see your own people’s stories reflected onstage. Qui and I were talking about it and he told me, and I hope he doesn’t mind that I’m sharing it with you today, he talked about how profound it was to be able to discuss that play with someone who was also Vietnamese, who understood implicitly where he was coming from.

Of course, I’m not the only one who loved that play; most of the critics who saw it did. But I guarantee that if I had written a review, it would have had a different focus. Our backgrounds affect the way we see the world, and what elements trigger us. If you grew up hyper-aware of sexism because you were a woman, or of racism because you’re a person of color, you are then more aware of it when you look at a piece of art. If you grew up with friends that run the gamut from new immigrants to people whose ancestors have been here for 1,000 years, then the way you view diversity is different than someone who grew up in an all-white suburb in Connecticut (no offense to anyone from Connecticut). It’s a lived experience, rather than one that is learned secondhand.

And if we have diversity in criticism, then we can have diversity in how a play is perceived. Critical opinions shouldn’t be a monolith; there should be variation. In variation, there is active discourse. In variation, there is richness.

So the question now becomes: How do we foster a more diverse generation of theatre critics?

On that topic: I have an anecdote. I was 22 years old and an intern at a New York publication, my first official New York City byline. Midway through the internship, I got up the nerve to ask the lead theatre critic if I could write reviews. He said yes.

I filed a grand total of two reviews.

The first one was pretty decent. The second one was an incoherent mess. It was a two-star review and I had no idea how to write about it, even though I had spent hours and hours over 500 words. No one told me that the reviews for mediocre shows are the hardest ones to write.

It took a good amount of editing and he didn’t let me review after that. I’m not telling you this story as an example of sour grapes. It was an example of something that was essential for me at the beginning of my career, and which I didn’t receive in that instance: an older journalist who could be a mentor, who could sit me down and teach me how to be a better writer.

Journalists do not emerge like Athena from the head of Zeus, fully formed and brilliant. They are nurtured and trained into being.

The only reason I am the journalist speaking in front of you today is because Jim O’Quinn sat me down when I wrote my first longform piece for American Theatre and walked me through the edits, paragraph by paragraph. And now, my boss, Rob Weinert-Kendt, regularly sends me a Word document with track changes on it. The only way to foster the next generation of journalists is to nurture them and to have patience. I’m a much better writer now than I was five years ago, and I didn’t do it alone.

The writers coming up today need the space to make a few mistakes, instead of a one-strike-you’re-out experience.

Of course, if a writer misses a deadline or doesn’t spell check, then you have my full permission to not use them again.

That is why training for journalists must be made accessible. Aspiring arts writers shouldn’t have to take out $80,000 in student loans to go to journalism school. Last year, I got an invitation by Chris Jones to attend the National Critics Institute at the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center. And the kicker was: the whole thing was paid for. I commend Chris for the work he did to make sure the NCI was accessible for people like me who couldn’t afford it. That experience reminded me that I had an opinion, and that I should share it.

Today’s aspiring critics and arts journalists aren’t found at newspapers; they might not be on staff at any publication. When the lead critic job at many of today’s publications is currently occupied by the people in this very room, where can the writers my age go to practice our craft?

Today’s aspiring writers have day jobs, and they’re a journalist on the side, writing for probably $50 a review, $150 for a reported piece. They are writing for free because publications believe exposure is a valid form of payment. These journalists are found on blogs and on Twitter. They’re coming through student papers like the Daily Bruin, through grad programs like Goldring. They’re a diverse demographic and they’re hungry to write. They just need the opportunity, the encouragement, and the funding.

This industry is only becoming more difficult and more of a passion project by the day (not unlike theatre!). Journalism as it exists right now is not welcoming to those who don’t have inherited wealth. And not every young person of color coming up will have their parent’s money to help pay rent on their apartment, while they intern for free or freelance for peanuts. My parents certainly couldn’t pay my rent. But I got lucky.

Many do not.

We need to find a way to ensure that newer critics are being trained and encouraged to write, and we need to find a way to pay them. My boss, Rob Weinert-Kendt, has been talking about creating a fellowship for theater critics of color. I don’t see why ATCA can’t do the same, or partner with American Theatre to help fund theatre criticism as the traditional outlets are shutting them down. If we want diversity, we need to be intentional about it.

I recently read articles on Buzzfeed and Poynter that said this: It said that journalists tend to mentor people who remind them of themselves. And since most editors are white and male, it all but ensures that this exclusive club of journalists remains homogeneous.

To end this speech, I want to leave with some bullet points on additional steps you can take immediately. In case you don’t realize by now, I love lists, a byproduct of being a millennial.

1. ATCA needs to revise its membership requirements. Instead of theatre critics, make it open to theatre journalists. I know that this change is currently being considered, and I just want to reiterate how essential it is if ATCA wants to adapt to the changing times and have newer, younger members in its cohort.

2. If you’re not on Twitter, get on Twitter. And whenever a young journalist tweets something interesting at you, or if you notice one of them following you, follow back. Keep your eye on them, share their work, and interact with them.

3. Take a chance on someone new—someone who may email you out of the blue without a referral. Mentor them. Let them write for your publication. Gather a list of newer journalists with potential, and whenever you hear about an opportunity for them to write about theatre, send out an email blast.

Somewhere out there, a young, poor kid of color is looking for someone to lead them into this field. Don’t wait for them to find the torch, pass it to them.

Thank you for giving me the chance to speak in front of you today. Now…bring on the questions!