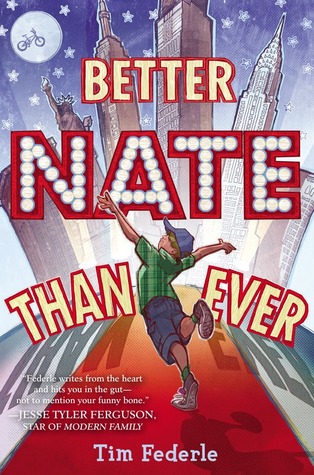

Nate Foster, newly cast in E.T. The Musical on Broadway, wasn’t sure what to write for his bio, having previously appeared onstage only as a piece of broccoli. “I’m allowed 50 whole words to describe a life spent hiding from bullies in bathroom stalls,” laments 13-year-old Nate.

By contrast, Tim Federle, the writer who created Nate, has plenty to put in such a bio: A professional musical theatre performer by the age of 12, Federle sang and danced in theatres around the country, from his hometown of Pittsburgh to North Carolina; shimmied in a Tina Turner wig behind Christina Aguilera in the Super Bowl halftime show in Atlanta at age 19; made his Broadway debut at 22 as a member of the ensemble in the revival of Gypsy starring Bernadette Peters, the first of five Broadway productions and national tours. By 28, he had worked his way up to dance captain and associate resident choreographer for Billy Elliot.

Then he quit at age 31 to become a novelist. Five years and seven books later, he is back on Broadway, this time in his debut as a librettist. Federle is serving as cowriter with Claudia Shear of Tuck Everlasting, a musical adaptation of a children’s book by Natalie Babbitt, opening at the Broadhurst Theatre April 26. Why this book? As Federle puts it, “It was one of the only books assigned to me in school that I read.”

If Federle’s trajectory is far from typical, it is nevertheless instructive.

“So many theatre people started as performers; performing is the gateway drug,” he says. A good example is Casey Nicholaw, Tuck Everlasting’s director and choreographer, best known for helming The Book Of Mormon, who hired Federle. The two met doing the New York City Center Encores! concert of Bye, Bye Birdie. “We shared a mischievous sense of humor; it is something that people who share dressing rooms develop,” says Federle. “We’re both reformed chorus boys. He was a dancer who became a choreographer, and secretly had a yen to be a director.”

Federle was initially unaware of any ambition to be a writer (“I thought writers smoked pipes and lived in Brooklyn”), though in retrospect he notes, “I was always more interested in the storytelling behind the steps.” Oddly enough, his stint in Billy Elliot is what made him see the light, which came from two different directions.

He had started taking dance lessons when he was 10. “When you’re a boy who shows any affinity for dancing, you get so much attention,” he says. “It happened at a time in my life when I felt ugly, gawky. I was also drawn to it because I was moderately good at it.” But working with the talented cast of Billy Elliot convinced him it was time for a career change. “These were 14-year-old boys who were better dancers than I was on my best day.”

They were also an inspiration, reminding him of his own experiences as an adolescent devoted to the theatre.

“Theatre gave me a place to go,” says Federle. “People say theatre is great because you get to escape and be somebody else. But I felt that it was the one place where I could be myself. Thank God I was born gay, different, and I had to push to get something of my own. I wasn’t a straight-A student, I didn’t play sports. So I had to develop a voice. The things that used to get me in trouble in school—I was the class clown, I was constantly in the principal’s office—are what get me paid now.”

Using one specific Billy Elliot actor as a model (“He was hilarious”) and merging him with his own experiences onstage and backstage, Federle created the character of Nate Foster. In Better Nate Than Ever, the intrepid youngster travels to New York for the first time to attend an open audition for a Broadway musical, and improbably gets cast. “Nate was younger than I was, but he was braver,” Federle says.

In the sequel Five Six, Seven Nate!, Nate moves to New York at age 13 to work in the show, allowing Federle to make some wickedly faux-naïf observations about the theatre world. On the first day of rehearsals, he writes, “Hordes of folks hug and kiss and whinny like at a family reunion you might see on a TV show….How could they all know each other already?…Everyone is in all black. Maybe today is a national day of mourning in New York.”

For all the with-it dish, both novels are geared to readers in middle school.

“A literary agent said writing for kids is booming—Harry Potter, Hunger Games,” Federle says. “Middle schoolers get every joke you make, but they’re not jaded.” Federle chose to begin his professional writing career with a novel rather than, say, a play, because “you can write a novel in secret; everything in theatre is so exposed. I was not ready to come out as a writer. You have so much control as a novelist: You’re the writer, the costume designer, the set designer, the director, and the actor.”

After the two Nate novels, Federle collaborated on a children’s picture book, Tommy Can’t Stop, about a hyperactive boy who irritates his family until he starts taking tap-dancing lessons and becomes a star. He then branched out into three drink recipe books with puns as titles: Gone With the Gin, Tequila Mockingbird, and Hickory Daquiri Dock, this last book aimed at parents with young children, which mashes up drink recipes with nursery rhymes (“Old MacDonald Had a Flask”).

After the two Nate novels, Federle collaborated on a children’s picture book, Tommy Can’t Stop, about a hyperactive boy who irritates his family until he starts taking tap-dancing lessons and becomes a star. He then branched out into three drink recipe books with puns as titles: Gone With the Gin, Tequila Mockingbird, and Hickory Daquiri Dock, this last book aimed at parents with young children, which mashes up drink recipes with nursery rhymes (“Old MacDonald Had a Flask”).

His latest book, The Great American Whatever, published in March, is his first Young Adult novel; it’s about a 16-year-old boy who dreams of Hollywood (rather than Broadway), but whose life and that of his family have changed because of a car accident. “The ideal reader for the new book is 16,” says Federle. “It’s a time in my life I’m trying to do over. I wish I had been a better student. I wish I had gone to college. I wish I hadn’t lost myself so much in my first romance as a teenager.”

That said, Federle isn’t just delighted with his new job as a librettist; he’s relieved. “What’s nice about returning to the theatre is, it’s a language I grew up with,” he says. “When you’re writing fiction, it’s all on you.”

The team had been working on Tuck Everlasting for half a dozen years before Nicholaw brought Federle on. “They wanted fresh eyes,” the writer explains. “I feel like I help edit.” His experience writing for young people has also come in handy, he notes: “The first thing you learn when writing for children is you never condescend to them. Winnie is young but intelligent.”

In Babbitt’s 1975 novel (which has been adapted for the big screen twice before), Winnie meets the Tuck family, who long ago drank from a spring that made them immortal. Tim Federle says he can relate: “I became a writer so that my work could live on. It is a type of immortality.”