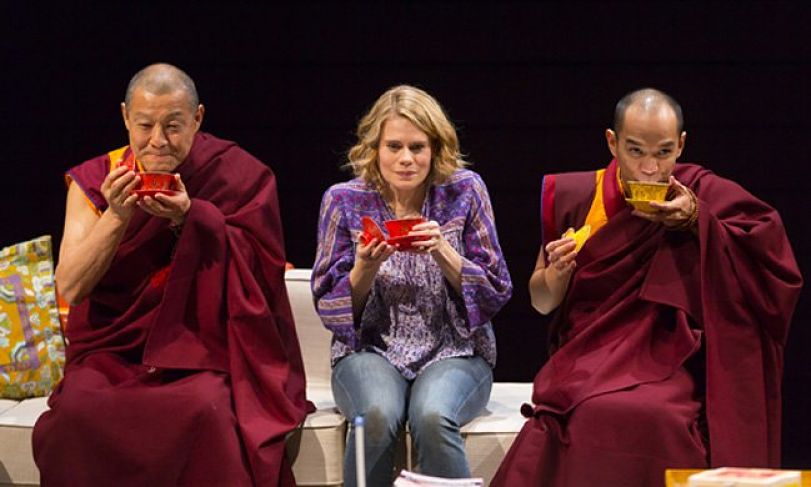

In Sarah Ruhl’s The Oldest Boy, an American mother’s world is shaken when she learns that Tibetan monks believe her young son is the reincarnation of a high Buddhist lama. Now Ruhl’s play, which had a critically acclaimed run at Lincoln Center’s Mitzi Newhouse Theater in 2014 and a number of regional productions since, is about to be put to charitable use to benefit a nation that was literally shaken, Nepal, whose devastating earthquake in April 2015 affected thousands of Tibetan refugees who live there. Readings of The Oldest Boy at leading resident theatres around the country, held to mark the one-year anniversary of the earthquake on April 25, will raise relief funds for victims of the disaster, which claimed more than 8,000 lives and injured at least 21,000.

The readings are being spearheaded by Ruhl herself, and a consortium of organizations have come together for the nationwide effort, including Arena Stage in Washington, D.C., Central Square Theater in Cambridge, Mass., Goodman Theatre in Chicago, Irondale Ensemble Project in Brooklyn, Lantern Theater Company with support from the Philadelphia Asian Performing Artists, the MFA in Playwriting Program at Brown University in collaboration with the URI Center for Nonviolence and Trinity Repertory Company, Shaking the Tree Theatre in Portland, Ore., and Soulpepper Theatre Company in Toronto, Canada. Companies producing full productions of the play in 2015-16 (including California’s Marin Theatre Company, Kansas City, Mo.’s Unicorn Theater, San Diego Repertory Theatre and Minneapolis’s Jungle Theater) are also set to participate in the awareness and fundraising effort. Proceeds of the nationwide readings will go to the Tibet Fund’s Emergency Earthquake Relief Fund.

Ruhl spoke to me recently about the play and the relief effort, and she was joined by Yangzom, the Tibetan nanny who helped inspire the play.

MELISSA CRESPO: Where did The Oldest Boy come from?

MELISSA CRESPO: Where did The Oldest Boy come from?

SARAH RUHL: I had heard this story about a couple who had a restaurant in Boston, and they were from Tibet, and one of their children was recognized as a high lama. So the question was whether to send the child to a monastery in India, which they eventually decided to do. I was told this story by my wonderful babysitter Yang Zom, who is Tibetan. I was fascinated by the decision a mother and father had to make: whether or not to let go of a child and let him be raised in a monastery.

Was that couple also both American and a Tibetan like in your play?

SARAH: No, they were both Tibetan. My sense is that if you’re raised in that culture, from a very early age, it’s normal to be raised in a monastery, and it would be easier to make that decision. In the story I told, there’s an American woman married to a Tibetan man, and they have to make the same decision. I think it’s harder for people to navigate questions of faith and culture when they come to it from very different childhoods.

I didn’t realize it was a real story.

SARAH: Oh, it’s real! And another crazy thing is that years later, when I asked Yang Zom what had happened to the actual family, she told me that they left their son in the monastery in India, then came back to Boston, reopened their restaurant and had a daughter. It’s precisely the way it is at the end of the play—and I’d already written the ending without knowing.

In terms of your relationship with Yang Zom as the nanny to your children, was this play deeply personal?

SARAH: Yes, absolutely. It was the first play I wrote after I had twins, so the experience of motherhood is deeply rooted in the play. I also have a husband who is half Thai, half Australian, and I’ve watched his family negotiate a family that is from both the East and the West. And the more research I did about Tibetan Buddhism, the more and more personal that part of the story became too.

Your children have been raised with both Eastern and Western influences. What kind of effect do you think it has had on them?

SARAH: It’s interesting; they have been told both stories. They’ve been told the Catholic stories that I was raised with, and they’ve been told the Buddhist stories that Tony, my husband, and Yang Zom were raised with. So sometimes they get confused about reincarnation. At Easter one of the children said, “What’s the big deal? If Jesus died, then he’ll come back. Everybody does that.”

The earthquake in Nepal happened shortly after the New York run of The Oldest Boy. Is that where the benefit idea came from?

SARAH: I was so saddened by the earthquake, and one feels so helpless, and I was thinking what can I do? Is there one small thing I can do to help? I thought about theatres passing the bucket for donations, and I had the idea to do a reading of The Oldest Boy so we could pass the hat. Then I had lunch with my friend James Yaegashi, who played The Father in The Oldest Boy, and he said, “Why don’t you think a little bigger?” He had done this amazing fundraiser called Shinsai: Theaters for Japan after the Japan earthquake. He did the event a year after the earthquake so he could plan. His fundraiser was really international in scope and involved a lot of different theatres and companies. So, inspired by James, I started reaching out to theatres to see if they would do a reading of The Oldest Boy and pass the hat for Tibetan refugees living in Nepal who are affected by the earthquake. I had done a number of projects with Tibet Fund when I did The Oldest Boy at Lincoln Center, so I already had a relationship with them. And a lot of people I talked to who have done relief efforts said that the news cycle is so short, so bringing attention to a crisis a year later is a wonderful thing, because people forget all about what happened. There are still people living in tents, people who are displaced, people without running water—there is still plenty of work to be done.

Lobsang Nyandak, executive director of Tibet Fund, told me that in addition to the funds raised, he is thrilled that audiences will be exposed to Tibetan culture, including its ideas about reincarnation. With so many Tibetans in exile, is The Oldest Boy also an effort to raise awareness of Tibetan culture?

SARAH: One thing that has inspired me when talking to Tibetan refugees is how much the culture is preserved in exile. It’s astonishing. There are more books, I think, published per capita in Tibetan than almost any other culture because the monastic culture is so scholarly; there is so much cultural production going on. I interviewed one lama at Lincoln Center during our process, and he said, “Tibet is an economy of culture. Our whole economy is based on culture: books, dance, music, and religion. When His Holiness the Dalai Llama went into exile, the first thing he did was set up a performing arts institute. So before an army, we need to preserve the culture for people in exile; a sense of identity comes through a sense of culture.”

Yangzom, what does being Tibetan mean to you?

YANGZOM: Being Tibetan means that I am lucky—that I am born in a religious space so I know what karma means so I will be a better person. We have the Dalai Lama always teaching us the meaning of compassion.

SARAH: Can you talk about your friend with the restaurant and the baby in the monastery?

YANGZOM: Yes, it is my friend’s daughter-in-law’s sister. They have a very good restaurant in Boston. She is a very good cook. They had a little boy, who was 6 or 7 years old. Some people say he is a reincarnated lama. Every lama that passes away is usually reincarnated very soon, usually not more than 10 years. But he had died a long long time ago.

SARAH: Do you know how he was identified?

YANGZOM: I don’t exactly know. But they took him to India to test if he was a real monk and they figured out he was.

SARAH: Do you know any Tibetans who remember their previous life?

YANGZOM: Most people don’t. But when babies are born—and when I was born—they make astrological papers and call the lamas. They look at the stars on the day you are born. They find out what your previous life is and how do you go on to the next life. My oldest son was born on Oct. 31; before coming to this country I didn’t know there was a holiday on that day. When we saw his astrological papers, they said he was a ghost in his previous life. When I came to this country, he really was a ghost! (Laughter)

SARAH: If one of your son’s was identified as a lama, would you be happy to send them to the monastery?

YANGZOM: Yes, but sometimes if a lama is born in a house, a really strong lama, it is not so lucky. Sometimes it means someone in the family will die. Luckily the family with the son who was a lama didn’t have anything bad happen. I remember another family who had a son who was a reincarnated monk. But the mother was really modern and very rich, and the son went to a private school and they didn’t send him to the monks. I heard that when he was a teenager he was out of control.

SARAH: It’s funny—this interview is not dissimilar from the origins of the play. I’d walk around and write and come in the kitchen and have a little chat with Yangzom.

What is your hope for this benefit?

SARAH: My hope is to a) get a little money to people who might need it in Nepal who are suffering. And I suppose b) to shed a little bit of light on the predicament of the Tibetan refugee community in Nepal. I think sometimes just shining a little light on a problem is a bigger thing than it appears to be, and it’s a modest aim. Shining a little light on that part of the world when the news cycle forgets things immediately.

I think a smaller goal is bringing together a community of people in a very local way, which always happens when you do a play, and which I always find moving. You can see that there are wonderful Asian actors across the country. And that also one can be creative in casting. The casting of this play is interesting because there are several Tibetan characters and also the character of the boy, who theoretically is a biracial child, who is the soul of an old man. How do you cast the soul of an old man, and does the soul have a race? It’s an interesting question. I’ve seen readings where that part is done by an African-American, a Jewish person, and a young woman. Part of what I hope is to open up possibilities of who can play what and expand people’s definition of what can be done.

Casting is definitely a hot topic right now.

SARAH: Yes.

And needs more ammunition to push people to open their minds.

SARAH: They do. To be clear, I do not endorse what Neil LaBute means when he talks about having colorblind casting both ways. That is not my intent when I say you can have the soul of a Tibetan person played by a person of any race, because I think that ignores political reality. But in our vital and important search to make our stages more diverse, and to make our stories more diverse and to make our production teams more diverse, there might be times when we have to open our minds to possibilities we haven’t considered. How can we do that without papering over political reality?

When I was casting this play I remember looking at the résumés of these amazing Asian-American actors, Shakespearean actors, film actors—beautiful actors—and you look at some of the roles they’ve played and it would be “Shopkeeper #1” and “Sexy Monk”—characters without a name. I myself have written characters without names as an attack on naturalism, actually. But I think it’s something to look at in terms of diversity. Why are so many people of color playing characters without a name?

Can you tell me more about this relief effort?

SARAH: Another thing that inspired me to try to do something for Tibetans in Nepal after the earthquake was how helpful every single Tibetan person was when I asked for help when I was doing The Oldest Boy at Lincoln Center. I called up a lot of people to ask questions about cultural authenticity. Every time, without fail, that I asked for help, someone on the other end said, “I’m glad to help you.” I remember the first time I called a Tibetan scholar at Emory to ask about reincarnation; he said, “I’m happy to help you because your play might benefit other sentient beings.” And I thought, “Oh, that is so wild—there is an cultural assumption that art is helpful!” By helping someone engage in a cultural activity, you are actually being helpful in a wider practical sense. And this was a very confidently held assumption I found when talking to Tibetan people; in the West we don’t always share that assumption. Or maybe among artists it’s a tacit assumption; you think, or you hope, “I might be doing something helpful.” But there is also so much self-hatred in the arts because our culture so often doesn’t value what we do. So we think, “Oh, we’re doing something self-indulgent, we’re making art, meanwhile we could be helping people.” The people I talked to from Tibet assumed we were trying to be helpful.

Assume best intentions!

SARAH: Yes! I found that beautiful. And I have to say it really shifted my understanding of the function of art and culture.