The artist and filmmaker Michelle Memran met the playwright Maria Irene Fornés on assignment for this magazine in 1999. As with many pulled into Fornés’s orbit, it was a meeting that would change Memran’s life and her work forever, but it also came right when Fornés’s life was about to change, due to circumstances entirely outside her control.

“I met Irene to talk to her for an American Theatre piece about playwrights and critics,” Memran recalled in a recent interview. “I waited to interview her last because I was most intimidated by her, most in awe of her. We talked for six hours. Almost none of it was about playwrights or critics. I started seeing her every week.”

Soon, Irene—everyone who knows her calls her Irene—told Memran that she had stopped writing and didn’t know why. The ideas were still there, but she could not concentrate and get them down on paper. She was still teaching, but it was becoming more of a struggle. Then, in 2002, Memran said, “I went into her apartment, which has always been a kind of memory theatre. She collects books and scraps, and she’d had that apartment at One Sheridan Square forever.” Memran could immediately tell something was wrong. “I began wondering who was taking care of her.”

Memran called Fornés’s agent and champion, Morgan Jenness, and told her she worried that Irene had dementia. According to Memran, Jenness—who warmly declined an interview for this story, saying that she believes others deserve the credit for Irene’s care—told her that she too was worried about Fornes’s well-being. In fact, Jenness had been trying to rally the theatrical community around taking care of Fornés for some time. Soon Memran was visiting Irene’s apartment whenever she could, taking her lunch breaks from work at a nearby magazine to bring her food.

Then, at Brighton Beach in 2003, inspiration struck. Memran had an old video camera with her, and she turned it on Irene and asked, “Does the camera make you uncomfortable?”

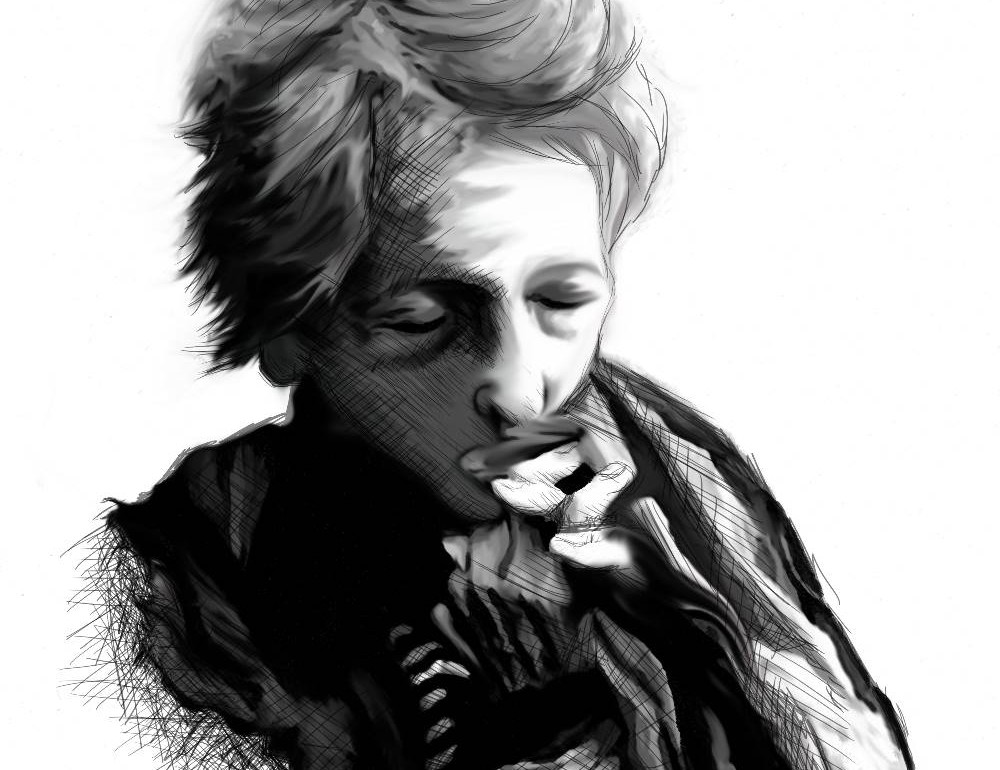

“The camera to me is my beloved, the one who wants me always, and I give everything I have to the camera,” Fornés responded, coyly, in what became the first day of shooting The Rest I Make Up, a documentary about Fornés that Memran finished a rough cut of in December. Memran used the film, in part, to bring people back into Fornés’s life, and received funding to take Fornés back to Cuba to visit her home.

“There’s all this curiosity about Irene as a person,” Memran explained. “The film is about this period in which she was no longer seen or heard as a teacher or writer. There was this sense that she couldn’t write, couldn’t teach—what was her value? I wanted to document that phase, to show that she was still as vital as she was when writing those plays. You spend 80 minutes solidly with her. The film is actually kind of a Fornés play.”

The film ends with Irene in Florida, where she received the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Soon thereafter she was moved to an assisted living facility in Oneanta, in upstate New York, hours away from anyone she knew. Jenness, Memran, and other friends traveled up to see her when they could. Then Fornés fell and broke her hip. She was transferred to a hospital, then to a nursing home, where she was placed on comfort care. The end seemed near.

The details of the story get a bit vague at this point. There was conflict between Fornés’s guardianship and her friends about what the best course of action was moving forward. Jenness, Memran, and others felt she would be best served by moving to a better nursing home nearer to people who knew her—that she seemed to be responding to familiar people, the familiar objects of her past, things that linked her to her former self, and that she was not as near to dying as had been assumed.

“The decisions that go into taking care of someone with Alzheimer’s are very complicated,” Memran explained. “We were filled with a lot of outrage at the moment. But there’s a lot that goes into these decisions, and on top of it, Irene’s family situation is complicated—lots of nephews and nieces from different siblings.”

Memran was quick to add that the relationship with Fornés’s guardianship is vastly improved today—that they are more cooperative and more involved in Irene’s legacy, and the end result of this struggle has been undeniably positive. A bed opened up at Amsterdam Nursing Home in Manhattan, close to her friends and theatrical family, and Fornés moved there. The Fornes Support Group, a Facebook group dedicated to advocating for her health, now helps schedule visits with her.

“When we got her into Amsterdam, they thought she would last a week,” Memran said. “She’s on her third year there. Contact and being surrounded by people who love you help you pull through. The first thing we did was surround her with her past and then reintegrate her back into the city.”

The ongoing push to care for Fornés, her work, and her legacy has led to a renewed push to raise awareness of Fornés impact on theatre. Hero Theatre’s “Festival Irene,” an important effort on that front, will bow at Rosenthal Theater at Inner-City Arts in Los Angeles from March 31 to April 10. The festival—which features staged readings of the work of Fornés and her students—was the brainchild of Elisa Bocanegra, an actor, arts leader, and the founder of Hero.

Hero is a theatre with deep roots in the parallel traditions that run through Bocanegra’s life: community-based work and the classics. As Bocanegra described her background in an interview, her resume includes stints at Williamstown Theatre Festival, at major theatres like Roundabout, on television and in film, alongside work “with a company called Latino Experimental Fantastic Theater Company, or LEFT,” Bocanegra recalled. “They got a grant to do a play about Latinos living with HIV/AIDS. This was about—gosh, 15 years ago. We went into different community centers. We did plays about Puerto Rican culture and different Latino cultures. We would go into communities to present theatre for our people.”

Hero’s most recent production was a revival of Waiting for Lefty, which offered free tickets to union members, and for which Bocanegra canvassed union halls. When asked what the resulting audiences were like, Bocanegra laughed and exclaimed, “They held up signs! We had all the carpenter’s unions in. It was incredible to see some of our audience members from more affluent backgrounds sitting next to a union worker with a child because they couldn’t afford childcare. I love the marriage of those two worlds. That’s what my company is about.”

A festival of Fornés’s work fits the company’s mission in part because she served as a mentor to Bocanegra since the two were first introduced by the playwright Migdalia Cruz. Bocanegra was then 18 and an aspiring actor.

“Irene took me salsa dancing and we ate French fries,” she recalled. “She was so smart, so passionate, so amazing. I started following her. I would go to anything she did, I just wanted her to talk to me,” Bocanegra said. Hero is ostensibly devoted to the classics, but that got Bocanegra thinking, she said, “What are the classic plays of my people? Of course the answer is Irene. She was a Cubana who came to this country and wrote these incredible plays. Irene defines my early career as an actress. So many call her la maestra.”

Bocanegra feels that Fornés’s work is important beyond its historical value for the ways it “gives voice to voiceless women. In her work, it feels like these characters are breaking through and speaking for the first time ever. She gives dimension and complexity to the male characters too. Take Conduct of Life: She doesn’t write about the man in that play as just abusive. She gives him all these gradations so you understand him in a different way.”

Festival Irene feels particularly urgent now, as it appears that the 85-year-old Fornés’s struggle with Alzheimer’s is in its late—even final—stages. This hasn’t stopped the playwright from being involved in picking the plays, Bocanegra pointed out: “The last time I visited her, we were trying to pick the plays in the festival. I would say the names of the plays and she would nod her head for the ones she likes. When she nodded her head, I knew I had the green light.”

The festival is just one of several interlocking efforts by theatre artists and academics aimed at preserving and, perhaps more importantly, expanding Fornes’s legacy—a legacy that has been at risk of dissolving into the ether. As Bocanegra put it, “Her work was never produced at the big regionals. I don’t understand that.” A quick search of TCG’s Theatre Profiles confirms this: It lists just 10 productions at TCG members theatres since 1995, four of them at New York’s Signature Theatre during its 1999–2000 season dedicated to her work, shortly before she became ill. Her work has often been performed and revived at indie/storefront theatres and at theatres devoted to Latina/o work. While 2010 saw a major festival of staged readings of her work organized by INTAR and NYU, Molly’s Dream, the last major full production of hers in New York City, ran at Soho Rep in 2003. Frank Rich’s The Hot Seat, which collects his writings about theatre for The New York Times between the years 1980–1993 (a period when Fornés wrote two of her most widely read plays as well as translations of Lorca and de la Barca), never mentions her. Even some histories of Off Broadway give her work short shrift.

Yet, as Hilton Als wrote in The New Yorker, she has “done more than her fair share in terms of changing the face of theatre in this country… Fornés always had her voice, which was inherently feminist and instructive without being self-serious.”

That voice took a while to develop. Unlike her contemporaries Sam Shepard, Lanford Wilson, and Megan Terry, Fornés did not complete her first play until she was in her early 30s. Fornés never finished high school, working instead in a shoe factory shortly after immigrating to the United States from Cuba at the age of 14. She moved to Paris to pursue painting and discovered theatre instead, seeing Waiting for Godot in French, a language she did not understand. She eventually moved back to New York and worked as a textile designer before moving in with her then-lover Susan Sontag in 1959, where it appears she began writing in earnest.

Plays soon followed: The Widow, Tango Palace, and The Successful Life of 3 all paved the way for Promenade, an Off-Broadway hit that ran for more than 200 performances and won the first of her nine Obies. In 1968, Robert Brustein mentioned Fornés in The New York Times (alongside Shepard, Guare, Wilson, etc.) as one of the playwrights of the “New Theater,” writers who, he wrote, “all share a passion for experimentation, all are original, all possess an individualized vision, and few would have had quite the same freedom to develop had they not found a home at the Open Theater, Café la Mama, Theater Genesis, Judson Church, or other of the numerous theatre hostels studded about the city.”

The creativity and experimentation during this period in New York City is the stuff of legend. It was a time when, as Lanford Wilson put it in an interview for the book The Playwright’s Art, “If Sam Shepard discovered something, it belonged to all of us. It was, ‘Oh good, we can do that, that is possible.’ It was very much like we were inventing or discovering theatre for ourselves.”

Yet this legend is almost always about white male writers. In part, this was because of how their work was covered at the time, and journalism is the first draft of history. Still it’s hard to fathom why a 38-year-old woman with a major commercial success was referred to as “a dark-haired girl with lustrous eyes,” as the Times’s Harry Gilroy did in a 1968 article about the playwrights’ service organization New Dramatists.

It seems clear that some of Fornés’s relative obscurity can be attributed to her being Latina. Her work was also less commercially successful than her peers. After Promenade, a major crossover success eluded Fornés. There is no equivalent in Fornés’s work to Guare’s House of Blue Leaves, Shepard’s Buried Child, or Wilson’s The Hot L Baltimore—plays acclaimed as both popular and aesthetic breakthroughs for their writers. The closest she came was a misbegotten effort called The Office, directed by Jerome Robbins and starring Elaine May, which closed on Broadway after 10 previews. Her major plays tend to be more openly political and darker than the work of her more commercially successful contemporaries.

But it may also be in part because Fornés stopped writing for six years to run a group of avant-garde playwrights called New York Theatre Strategy. It was only after, according to a 1987 interview, she “hired other people to coordinate Theatre Strategy” that she could return to writing and “worked on Fefu and Her Friends.” Fefu, which won her her third Obie, stands alongside Conduct of Life and Mud as her best known work (it is published by PAJ Publications and distributed by TCG).

Fornés’s plays have been kept alive by colleges and Latino theatres like INTAR, where she taught for many years. They have been kept alive in the minds, souls, and words of the many playwrights who cite her as a major influence. And they have been kept alive by the many artists and critics who marveled at them throughout the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s. But, in a sad irony, the resurgence of energy around her writing may owe something to her fight with Alzheimer’s and the recent struggle to save her life.

The other major push to preserve Fornés’s legacy focuses on her teaching. Indeed, Fornés’s most enduring work may prove to be as an educator. As Migdalia Cruz, who studied with Fornés for many years, told me, “I think Irene is our Stanislavsky. She is the premier teacher of playwriting in the world.” The link to the Russian master may not be so far-fetched: Fornés pioneered her own methods of playwriting, based in part on her experiences at the Actor’s Studio. According to Cruz, “There’s a lot of sense memory exercises.”

In interviews, Fornés has likened her workshops to the painting workshops she took as a young artist. “Unlike most workshops and classes that exist in universities, where you go home and write, bring your writing to class, have it read and get criticism, the Lab is all about inducing inspiration,” she said in an interview for the anthology Modern Drama. “In painting classes, you paint together; you don’t paint, bring your work to class, and have it criticized.” Her emphasis was always on inspiration. “Since I began writing I have always played games. The very first time I sat down to write I looked around and saw a recipe book. I opened the book and using those ingredients I wrote a crazy story.”

Cruz’s description of a day working in Fornés “laboratory” begins with the physical. “We started with half an hour of yoga or tai chi. Get your body loose. Get the nervousness out of it. Try to focus that misplaced energy.” From there, Fornés walked her students through a sense memory exercise. “For example,” said Cruz, “think of a time when you were 10 and you were by a body of water. Put yourself in the memory. Draw a sketch of it, or remember the light, the taste, the smell, so you are grounded in that memory.”

Once writers are grounded in memories, they then start bringing characters into it. “And then you get a prompt,” said Cruz. “The prompt might be that she’d give you action to read a book, and there’d be an object, a red shoe, and a word, or an emotion, or maybe a line from a random place. It might sound simple, but it’s a deep and sometimes mystical journey. Writing—at least my writing—is an act of remembering. Irene’s method allows you to do that, encourages you to do that, demands that you do that.”

Fornés taught in many places, but her most significant impact was as the leader of the Hispanic Playwrights in Residence Lab at INTAR, where she taught scores of writers. According to Cruz, “Almost everyone you speak to who is an American dramatist would say that they’ve been influenced by her, either through direct contact or studying under her students, like Eduardo Machado, who teaches at Columbia, or Caridad Svich, who uses her methodology.”

Thus does the effort to preserve Fornés’s legacy extend to her pedagogy as well. Anne-Garcia Romero, another former student, has written The Fornés Frame for University of Arizona Press; the book uses Fornés’s work and teachings as a lens through which to examine Latino playwrights in the United States. Scott Cummings, who runs the theatre department at Boston College and published a book-length study of her work for Routledge in 2012, is working on a book of her teaching methods. “It was hard for him to wrench those exercises out of my little fingers,” Cruz said, laughing, adding that she knows “the right thing is to get them out so people can learn from them and use them. But I also think the right thing is for her to get credit for doing this work. She’s a brilliant artist, a brilliant woman, and her legacy needs to be honored.”

For her part, Cruz is honoring that legacy on multiple fronts, including spearheading a pedagogy project devoted to Fornés. “I’m trying to get her students together to record her exercises together,” Cruz said. “What do we remember happening in that room? Create a document of her methodology and pedagogy, like Stanislavsky’s An Actor Prepares. I want people to have to say, ‘This is a Fornésian exercise.’ So that she’s given her due. We hope to one day certify teachers in the Fornésian Method of Playwriting through the establishment of the Fornés Institute, which is currently being championed by the Fornés Steering Committee of the Latina/o Commons of Howlround.”

The initial document will begin its gestation in a convening of many of Fornés’s students, including Cruz, Cherrie Moraga, Bernardo Solano, Ela Troyano, Leo Garcia, Lorraine Llamas, Holly Hughes, Anne Garcia-Romero, and Jorge Ignacio Cortiñes, with the hope of involvement by Caridad Svich, Eduardo Machado, Ana Maria Simo, and Nilo Cruz in the final document.

Not coincidentally, many of these writers are also involved in Festival Irene.

“I thought it would be great to present Irene’s legacy through the playwrights she taught at INTAR, because these are the playwrights I grew up doing,” Bocanegra said, adding that she also wanted to focus on the work that those playwrights did while studying with Fornés. “She wanted her students to bring all of themselves to the page, to make visceral characters, to make painful characters. Everything was there. She required they write from a place of truth and honesty.”

Based on the response to the various offerings of the 11-day festival, Hero will select one of Fornés’s plays to give a full production. Before that can happen, though, Bocanegra is working like a field marshal to get all the logistics ironed out. The plays—all dozen of them—are cast in repertory, so the scheduling alone is daunting. Bocanegra is trying to line up more sponsors, get the posters made, finalize rehearsal schedules.

It is, as she put it, “a lot.” But it is also “time. It’s time for this to happen. It’s been a long time coming. And I hope we’ll do it in New York next.”

Close to where Fornés is, of course.

Correction: An earlier version of this story stated that Fefu and Her Friends is published by TCG. Although the play is distributed by TCG, its publisher is PAJ Publications.