If by some chance you’re unfamiliar with the large swath of dance history Mikhail Baryshnikov occupies, you might have more recently seen him in his latest guise: as a performer in avant-garde theatre.

In Forbidden Christmas, or The Doctor and the Patient (2004 at New York City’s Lincoln Center), he acted as a Charlie Chaplin-ish car; in 2007 he costarred with Bill Camp to critical acclaim in JoAnne Akalaitis’s Beckett Shorts at New York Theatre Workshop. Or perhaps you caught him in Dmitry Krymov’s In Paris (2012), or spotted him on tour with Big Dance Theater’s heralded Man in a Case (2013–14), which toured to Connecticut, Chicago, Boston, and California. Or maybe you saw him cavorting alongside Willem Dafoe in Robert Wilson’s The Old Woman at Brookln Academy of Music?

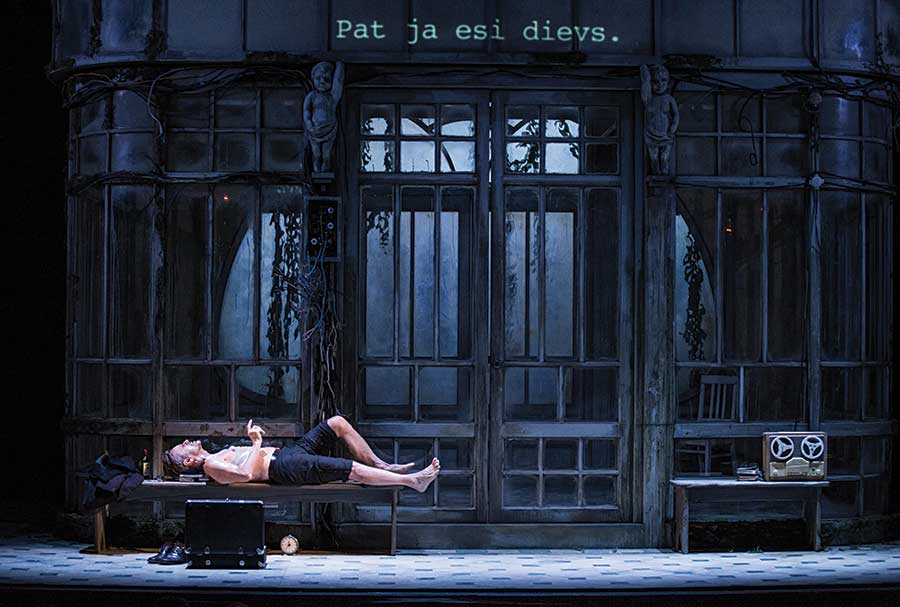

Last summer he premiered a new work directed by Wilson, Letter to a Man, adapted by Darryl Pinckney from the diaries of dancer/choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky, at Italy’s Festival di Spoleto; the piece also played Milan in the fall and will next appear at Madrid’s Teatros del Canal May 12–15 and at the Salle Garnier in Monte Carlo, Monaco, June 30–July 3. And last fall he opened Brodsky/Baryshnikov at the New Riga Theatre in Riga, Latvia, in a production conceived and directed by Alvis Hermanis; its U.S. debut is scheduled for March 9–19 at Baryshnikov’s eponymous arts center in New York City. The performer was a close friend with the late poet Joseph Brodsky, a Nobel Prize winner and this country’s poet laureate in 1991, and Hermanis is one of Europe’s leading contemporary directors.

“Creating work on Misha is a dynamic intersection with a particular part of dance history,” says Annie-B Parson of Big Dance. “This is a dancer who worked with some of the greatest abstractionists of the 20th century, including George Balanchine and Merce Cunningham. He owns a part of dance history; he literally embodies these dances and how they were made.” Still, she points out, “He is not tethered to his past; his eye is always on the future. Misha is curious; he comes from an intellectual tradition; he knows poetry and literature. Misha is artistically restless, in the best sense of the word.”

That restlessness may explain not only why his dance card as a performer is so full, but also why he runs Baryshnikov Arts Center (BAC) in midtown Manhattan. Now celebrating 10 years in operation, BAC presents a multiplicity of work—this season alone featured everything from dance by Joanna Kotze and the Aakash Odedra Company to theatre by Daniel Fish and Ronnie Burkett’s Theatre of Marionettes—and provides residencies for such varied theatre groups and artists as Pig Iron Theatre, Young Jean Lee, Richard Foreman, and Branden Jacobs-Jenkins.

“As a presenter, Misha is thrilled when he sees new ideas and is committed to supporting a huge range of artists,” says Parson. “I feel his work to create and sustain an arts center has not been celebrated enough. BAC is one of the most generous places for dance residencies.”

American Theatre magazine caught up with the actor/dancer/artistic director last year before the premiere of Letter to a Man. We drank tea; he wore a large ice pack under his shirt for nearly the entirety of the interview (“I have little injury,” he explained). What follows are excerpts from our conversation.

ELIZA BENT: How did Letter to a Man come about?

MIKHAEL BARYSHNIKOV: I was working with Willem Dafoe on The Old Woman with Bob Wilson, and we were chatting in Italy over dinner about interesting literature and how it gets adapted. What’s the difference between a play written by a playwright like Albee or Pinter or Sam Shepard and an adaptation, which is what Bob usually does? The conversation turned to Edwin Denby, the famous poet and extraordinary dance writer. He participated in Bob Wilson theatre marathons and he would read from the stage the whole of Nijinsky’s diary. They were very close friends, Edwin and him.

Bob was fascinated by the history of a man like Nijinsky, the divine madness of this man, and his relationship with Diaghilev. He was a wunderkind with a short but illustrious career. And then the whole story about his marriage, his split with Diaghilev, and the leap into the madness. His writing is a fascinating document, which was completed in six months and became a bestseller.

We talked a little bit about what roles I’ve done. I am such a different dancer from Nijinsky; certain things unite us, though. We both come from the provinces and moved to Leningrad-slash-St. Petersburg and finished school there. And then a few years later we both left that country and never returned. The rest is very different—180 degrees. Our temperaments. I danced some roles created on him. Bob said, “Well, maybe you should think seriously about a project like this, and I’ll read through the book.” For him it’s a sentimental issue. For the dance writer Denby, Nijinsky’s autobiography is like a bible.

So then The Old Woman went to sleep for a while—we did 80–90 performances of that play—and we decided to go with Letter to a Man.

What’s it been like to embody such a different dancer from yourself?

It’s not a story of the man; we’re not trying to look through this literally. People are shocked by the autobiography. Henry Miller, when he read it, was so stunned by how extraordinary and how raw and naked and honest and strong the material reads. He has some great quote about how if madness hadn’t stopped Nijinsky he would also be remembered as a writer—I’m paraphrasing.

Bob gave the book to Darryl Pinckney, a writer and dramaturg and fellow New Yorker. He’s worked with Bob for many years; he adapted Daniil Kharms’s The Old Woman. Darryl will come up with the text. I am totally passive; I am an actor. The text is between Bob and Daryl. Lucinda Childs is also involved—it’s not choreography per se, but she is an extra pair of eyes. She will be with us the last few weeks of rehearsals.

Tell me about the development process.

Like everything else, we work between Bob’s other engagements. We met a few times in Milan. In theatre, everyone is involved at the start, so there were 20 people from the first day of the rehearsal. Bob goes from A to Z. He does his homework. The first few rehearsals he comes up with a storyline and he puts on the wall the materials and explains where he is going visually.

Are you a part of generating the movement?

He is initiating movement himself. There is a lot of slow motion and then sharp and different speeds. He is totally unpredictable. He doesn’t even know himself what is next. He comes up with the rules and then he crashes them—then he comes up with a new set of rules and crashes those and rejects them. He’s very intense. Sometimes he works very fast and then sometimes he digs into the material until he makes, from his point of view, a step forward.

That style of working almost sounds like Kharms’s text—abrupt and unpredictable. So, to be clear, Letter to a Man’s not “Baryshnikov as Nijinsky.”

No no no! It’s a manifesto of an artist. There are pages that feel like they were written just yesterday by somebody who is really enchanted by the divinity of art. It’s about the relationship between an artist and divinity—the divinity of creation and working on your craft. Nijinsky puts this on the same level as his relationship with God. You know, his nickname was “Clown of God.” He was mysterious. It’s a tragedy that disease struck him so young.

People observing him during the Diaghilev period thought he was very quiet. No one thought he had much brains, just God’s gift. In fact, he was much more complex. He opened a new era of choreographers—with Diaghilev’s help, of course, and Stravinsky and the rest of the bunch. His relationship with Diaghilev, his life, his split, his marriage, and his sexuality—it’s all in Darryl Pinckney’s material. On verra, as the French would say (“we shall see”). We are in the last stage.

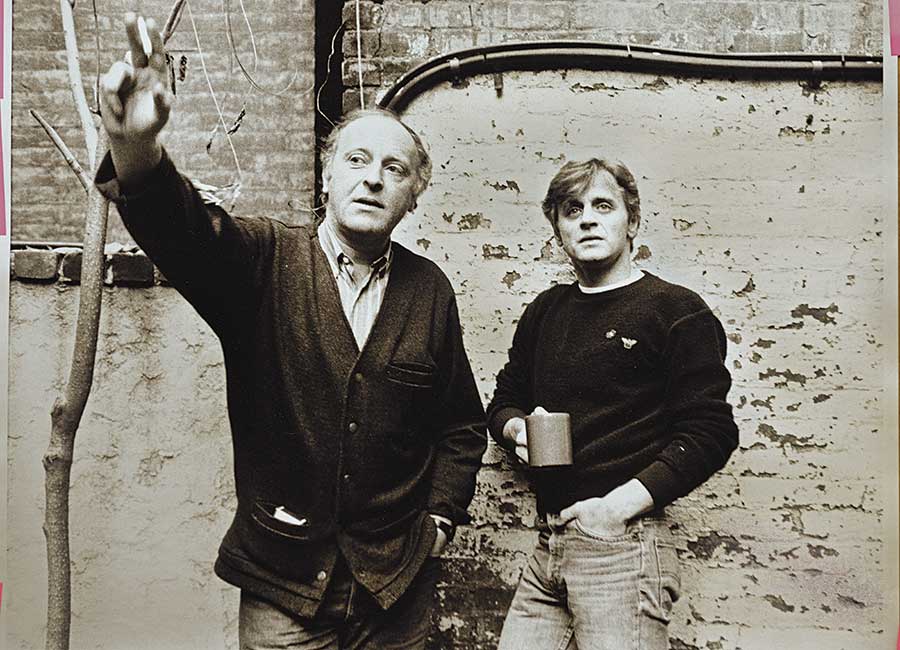

Tell me about the Brodsky piece you’re doing with Alvis Hermanis.

Alvis approached me a couple years ago. I knew his theatre work, he’s from Riga—we are from the same place. He is more known in Europe and Russia. He is a huge talent, very unusual and brave and straightforward. He is a visionary theatre director.

We met again at La Scala when I was seeing one of his operas. He knew I was close with Joseph [Brodsky] and he asked if I wanted to try something that wasn’t just reading the poems. It’s a tradition in Russia to read poems; it’s not done so much here, although I recently saw Charlotte Rampling doing Sylvia Plath at the [Park Avenue] Armory, which was excellent. Usually in Russia, well-known actors will do Pushkin or some prose, but it’s just reading. Alvis proposed we make a piece of theatre with a journey and an intricate set. It’s very different. I never imagined something like this, but I trust him.

How is the set intricate?

It’s a big set! There is a room that’s not quite a room. It’s very poetic and beautiful. Alvis chose close to 50 short poems. The show will be about an hour and a half. There is no dance, but there is a body language we will use. Alvis grew up on Brodsky; the poetry affected him as a young man very much—Brodsky’s artistic vision, his humanity, and his civic persona. In Baltic countries and Scandinavian countries he is a hero to everybody who had a little brain cell on their shoulders in their head. At a tender age Alvis started to read and listen to Joseph’s poetry, and he had physical convulsions over it! So one day he wanted to do something theatrically using Joseph’s rhymes and language, and that’s what he proposed to me. How could I not say yes? Alvis’s work is brave—he takes on subjects that are sometimes very touchy and difficult.

I remember interviewing him in 2009, and we spoke in very broad strokes about the reasons why people see theatre in different countries: In the U.S. it’s for entertainment, in Germany it’s for political reasons. He suggested that in Latvia people attend theatre for spiritual reasons.

That’s sort of Latvian theatre and Latvian art in general. Latvians have always been squeezed between foreign elements: Germany and Russia and Sweden. In Russia there was a psychological theatre tradition before the new formalistic style. Of course, there is formalism of German culture. My father was a Russian dignitary; I grew up there.

It’s interesting how Alvis’s view intersects with where his theatre in Latvia stands. He is such a fresh voice. He’s doing more opera recently. Theatre, it’s a lot of little details, but with opera it’s a concept! He is involved in the general concept, although he makes people do a lot in his opera productions.

You have had a hugely multifaceted career as a dancer. How does dance inform your approach to theatre?

Well, of course, directors are directors. They have certain instincts. I was not a director or choreographer. I collaborate with people. Some people give me a little longer leash, a carte blanche. Or a very short leash. [Laughter.]

What’s the leash length you prefer to work with?

Oh! As long as the result is good. If the director is smart, he changes the approach immediately. With Alvis we worked for a few weeks, and we now work every day on Skype, which is totally new to me. We are doing two and a half hours almost every day. We read through the poems he selected and discuss how and what is possible.

It’s a journey. It’s not just reading it to the audience. We are trying to get into the meat and the melody of the magic qualities of Joseph’s work. And it’s in Russian, with poetic elements of translation.

Let’s talk about BAC. You are busy enough with your artistic career. How do you have time to lead an arts organization?

This is my main job—this is a commitment for the rest of my life. I’m on Skype or on the phone wherever I am, whether I am in New York City or in the Dominican Republic at my summer house. The BAC programs are a commitment. What will happen after me is a decision for the board of directors, but while I am here I set up the programs and we have a great team. I am the artistic director of the umbrella of BAC, but we have an extraordinary group at the office who are devoted and smart and very interested in all art forms. People apply for grants and we screen them. It’s an umbrella: We do music, dance, theatre. It’s rare that we produce; we are mostly hosting. Of course, we also work with Theatre for a New Audience, and there is always an open door for Elizabeth LeCompte and the Wooster Group, and Peter Brook. And also some Russian theatremakers, including Cazimir Liske.

How do you sustain your energy with so many things going on?

I’ve done this all my life, from when I started to perform at age 10 or 11. The older you get, at least in your mind, time shrinks. You accelerate your speed because you feel that time is ticking and you want to fit unfinished business into your calendar. You give up on certain pleasures, like your golf handicap!

And you work with a real range of people from Annie-B and Paul Lazar of Big Dance Theater to Bob Wilson. What’s the connective tissue among these projects?

They all very much want me to use my voice and Russian language. The musicality of the Russian language is important for Nijinksy, and of course for me it’s such a pleasure to speak my mother tongue.

How’s your Latvian?

I understand it very well, but I left that country so long ago. Now people are emigrating, and it doesn’t matter what language a performance is in: Chinese, Spanish, Russian. People interested in theatre are well informed. When Willem and I were in Brazil, they were reading Daniil Kharms in Portuguese and they knew the material. You want to go see The Brothers Karamazov, you first go read Dostoevsky. Especially in Asian countries, when people come to see Russian theatre—or any other theatre, English or American or Polish theatre—they know the story. They are prepared!

Do you think audiences are less prepared in the U.S.?

Yes. In Europe, people speak two or three languages. You can’t get a job without it. And you get a better job if you can speak 4 or 5. Here it’s English über alles. My kids don’t know Russian, but my son speaks fluent Spanish.

How did you end up with a house in the Dominican Republic?

I had a house in St. Barts for years, but then that place got “discovered” and there was no quiet. It became a boutique island, and I left. Oscar de la Renta asked me to do a command performance for a charity, and he invited me to stay with him in the Dominican Republic. So I moved from St. Barts to Punta Cana and built a house there right on the ocean. I have a studio there. Alvis brings his family and kids.

Some people know you less as a world-renowned dancer and more for your appearances in film and on TV. Do you find there are misconceptions of you?

I never think about those things. I take everything I do seriously, whether it’s photography or an appearance on TV. I work with Annie-B Parson and Paul Lazar and Bob Wilson because it’s avant-garde theatre. If you want to be on the edge with the theatre you have to sing, you have to speak languages, you have to dance. It’s such eclectic work now.

I’ve worked with a lot of people. And whether it’s Twyla Tharp or Mark Morris or Merce Cunningham, you have to find your own personality in the neutrality of modern movement. It’s an open field. Of course, you have to do exactly what they want you to do, but there is a lot of air, because they are looking for something very fresh. You need to be a real chameleon, because people are always looking for something different all the time. Sometimes we all fail. Sometimes it works.

What’s your advice to young people looking for training today?

If you want to be in any kind of art form—musical theatre, drama, dance, Broadway—you have to start from your very early years and really learn how to read music, how to sing, how to dance, how to train your voice. Every few years the accents shift on what kind of theatre people make. It’s interesting how people who really thought they would do traditional theatre then do an HBO series, or Hollywood people end up working on Broadway. Priorities are changing. Indie films are more interesting than Hollywood movies. There is an invasion of English-speaking actors from other parts of the world.

What’s your relationship to criticism?

I read reviews. My skin is not as thin as it was once. I have to read reviews, because BAC is reviewed all the time. Being in the arts is not for sissies. You have to be smart about unkind notices.

How so?

You need to separate nastiness from constructive things, no matter how painful it is. You need to ask, “What kind of lesson can I get?” Ultimately it’s all personal opinion. Some people love the tenor of Pavarotti, others prefer Domingo. Sometimes you can adjust and adapt the suggestions of the journalist, but not always. You have to respect the dignity of the theatre, and if you decide to be in this business, you need to be brave and strong and keep going.

That’s good advice.

Theatre is thin ice, because you have to be transparent and the material has to be transparent, and you have to deliver a fragility of movement, character, voice, and be there. Be present with your partner onstage. Every time I go onstage I have a butterfly in my stomach. Even if I’ve done the show 50 times. [Big sigh] I have to breathe deep and relax and go through the routine.

What’s your preshow ritual?

I have to warm up and physically be ready. The makeup for The Old Woman alone takes an hour! Then I do a two-hour warmup, so I end up arriving three hours before the show. It’s a commitment. But it’s a pleasure—that’s why I do it. Otherwise why bother? Life is too short.

Playwright and actor Eliza Bent is a former senior editor of this magazine.