As high school seniors gear up to embark on their next chapter, performing arts students have more on their minds than just extracurricular activities and SAT scores. Thousands of 18-year-olds are polishing their monologues, practicing their slate, and printing copies of their résumés—all to compete for the few coveted spots in undergraduate drama programs. And while other high schoolers denounce the Common App, students with their eyes on a B.A. or BFA in theatre must audition for each school in addition to applying and writing essays, all with an additional price and added anxiety.

The University of California—Los Angeles audition tour stopped in New York City just in time for the snowstorm Jonas on Jan. 24, bringing students from across the country—some as far as Hawaii—to audition for the Ray Bolger Musical Theater Program at UCLA’s School of Theater, Film, and Television (UCLA TFT).

I was once one of those nervous teenagers vying for an acceptance letter, and sitting on the other side of the table to observe the UCLA auditions took me back. A few key—albeit traumatic—memories that stuck out were being chastised by an audition monitor for not knowing A.R. Gurney’s full name (I now know it’s Albert Ramsdell Gurney Jr., and I’ll never forget it), and the numerous times my two-minute audition monologue was cut short, after spending hours traveling just to get into the room.

Needless to say, I was anxious for the 31 hopefuls.

Auditioning for the program costs $70, which is in addition to the cost to apply to the school itself. (The cost to audition for different universities can vary.) Students will find out in May whether they are accepted into the program, and before they can be considered for it, they must be accepted into UCLA academically first. In the end, 20 actors and 18 musical theatre students will make the cut, alongside 28 miscellaneous theatre practitioners (directors, designers, playwrights, etc.).

The students and their parents began the day-long process with a welcome session led by Rich Rose, a scenic design professor who has spent many years auditioning candidates for UCLA’s program. “I want to make sure that you have the right tools in order to decide which school is right for you,” Rose said. Before sending everyone off to the dance call, Rose reminded them to look “just above the auditioner’s head” while delivering their monologues.

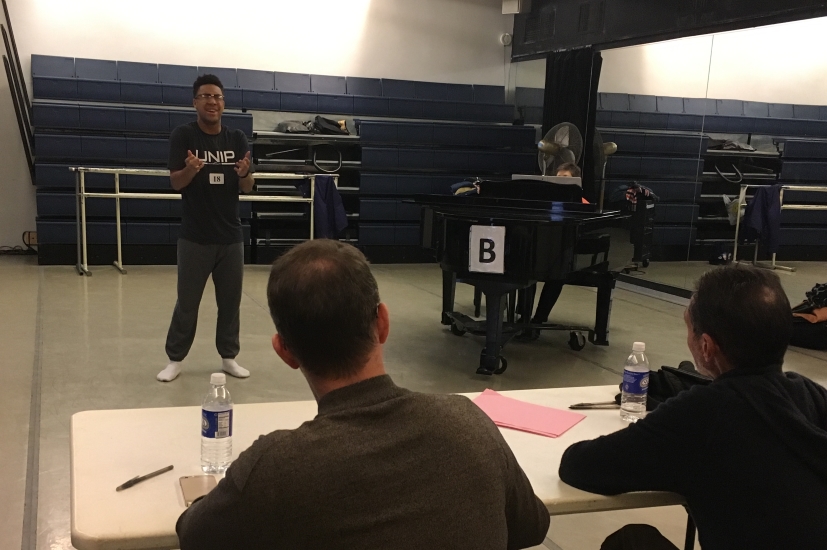

The dance call can be the most terrifying part of an audition for musical theatre students with a set of pipes and two left feet. And while the skill levels of the dancers I saw varied, the enthusiasm in the room—perhaps fueled by the Gloria Estefan music—was evident. The students were split into groups, and in the corners, they helped each other learn the choreography. “Starting with the dance call is psychologically good, as it channels any nervous energy,” explained Brian Kite, new chair of UCLA TFT’s theatre department. The dance call is one of four sections of the audition process; auditionees also sing, perform monologues, and are interviewed. After the dance call, the other portions took place simultaneously, with different faculty members serving as the monitors for each.

The students performed two monologues—one contemporary, one classic—and were asked questions about their characters. Perry Daniel, a professor of movement and acting at UCLA and one of the monologue monitors, gave students adjustments and scored their auditions based on physicality, vocal quality, creativity, connectivity, and preparedness.

Meanwhile, interviews with faculty members were taking place in the adjacent room. Students were asked questions about what electives outside of the theatre curriculum would interest them, and what they were currently reading for leisure. One student expressed wanting to take a philosophy class, and talked about George Orwell’s 1984. The discussions weren’t about what shows they performed in in high school or what their dream role would be; the interviews were conversations to find out about the students’ offstage lives.

“We want actors who are intellectually curious and want a B.A. program where they can pursue interdisciplinary studies alongside their training,” said Kite. “We want well-rounded, smart artists.”

Across the hall, students were queuing up to sing their song selections—the part of the audition where they can showcase their vocal chops, their acting skills, and some movement. Monitors took notes on the students’ability to be present, acting potential, and vocal health.

I took a deep breath each time a student collected their songbook and headed for the door, awaiting the onslaught of commentary about their poor song choice or their outfit (at least, this is what actors think gets talk about after they leave). Instead, the silence in the room was broken with talk of the snowstorm outside, or the lunch options in Midtown. Perhaps the adage of the audition monitor wanting you to be good is actually true.

I think back to the trusty blue binder that accompanied me to each of my school tryouts, filled with audition details, monologue materials, headshots, and dismal stats about acceptance rates for each school, and wonder if all that baggage may have clouded my own experience. Perhaps the stress of applying for schools overshadowed the educational experience that auditioning for schools can actually offer—and the underlying fact that talent isn’t always the deciding factor. For those on the other side of the table, putting together an incoming freshman class is like putting a puzzle together.

As a freelance director, and former producing artistic director of La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts, Kite is no stranger to being in the director’s chair. But this is his first year being part of the selection process for the four-year program at UCLA, as he became the department chair in the fall.

“I feel more responsibility to get it right—we do shape, change, and steer people’s lives,” he said. “If they choose to go to UCLA, their life is going to be a lot different than if they choose NYU or Northwestern or another program. There is a lot of responsibility with that. The audition process is really about matching the student up with the right school.”

Kite isn’t alone. Theatre departments across the country grapple with piecing together the classes that they will work with for the next four years, and ultimately in the field. “I want students to know that we are on their side,” said Grant Kretchik, head of BFA acting and associate director of Pace University’s School of Performing Arts. (Full disclosure: I received my B.A. in acting from the school.) “They are auditioning us as much as we are auditioning them, and we are both looking for a happy marriage.”

Barbara Mackenzie-Wood, professor of drama and former chair at Carnegie Mellon University, has been part of the school’s audition tour for the past 15 years. She looks for students with spark and the ability to play with their material. “Ultimately, we struggle over the final choices, of course,” she said. “We will see too many talented people that we cannot take into our program. What I always say to them when I’m in the room with them is, ‘Spread your net wide, audition at a lot of schools if you can afford to.’ There is not a right way to do this, and CMU might not be the right place for you.”

At the completion of UCLA’s audition day, Brian Jackson, a high school senior from Maryland, reflected on the process. “I know I wouldn’t be happy doing anything else—I am very determined, and I will persevere to get what I want,” he said. Thinking back on the dance call, monologue, song, and interview, he said he enjoyed the audition process. “It is turning on the people who should be here, and turning off the people who shouldn’t,” he said. “It is a very upfront experience—if this is what you want, you should come here. It’s all a matter of where you fit.”