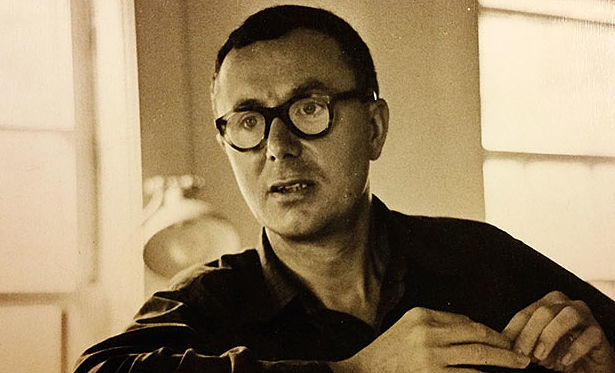

Eric Bentley has not gone soft. But at age 99, the British-born critic who wrote The Playwright as Thinker and introduced the English-speaking theatre to the works of Bertolt Brecht—among an eventful career’s worth of noteworthy achievements—has well earned the right to be circumspect about his body of work, about the art form he greatly influenced if never personally mastered, and about the cultural health of the nation he’s called home since becoming a citizen in 1948. And so, as he sat in a plush leather chair for an interview last December in the study of his home on Riverside Dr., with a view of a Joan of Arc memorial statue that one of his idols, George Bernard Shaw, might have appreciated, Bentley alternated between dispatching ready answers to questions he’s been asked hundreds of times and taking the time to think through philosophical and aesthetic quandaries he’s still, after all these years, wrestling with.

It is that wrestling—his rancor-free but nevertheless uncompromising lifelong tangle with ideas, both as expressed through the theatre and outside it—that keeps a reader returning with interest and pleasure to Bentley’s work. Though he was only a proper critic, in the sense of being employed to review current theatrical offerings on a regular deadline, for a handful of years in the late 1940s and early ’50s (for The New Republic and The Nation), in his major books and essays he brought a sharp, systematic mind and exacting if wide-ranging taste to a task few had taken up before him, and nearly none have since, outside the halls of academia: fashioning a long-viewed yet fine-grained critical history of Western drama up to the present day.

Alas, that “present day” more or less stopped at mid-century; though he considered himself an ally of many ’60s liberation movements, in particular gay rights (he himself came out near the end of that decade), he wrote precious little about the theatre of that time, let alone after. His health currently renders him unable to travel outside his home; even so, there remain intervening decades of substantive theatre (Shepard, Sondheim, Churchill, Kane, Kushner, assorted Wilsons, Mamet, Vogel, Nottage, etc.) about which he has been effectively silent. He has spent some of the intervening decades teaching, as well as writing his own plays, which include Are You Now or Have You Ever Been?, Lord Alfred’s Lover, and Round Two.

Still, the shadow of his seminal collections—which include What Is Theatre?, In Search of Theatre, and The Life of the Drama—continues to hang over what passes for critical discourse today, and it would be a grave mistake to consign his books to history, or to the timeworn aesthetic and political arguments from which they sprung. As with the greatest critics, it is not Bentley’s judgments but his insights that make him most valuable, though these can be hard to untangle, of course. And it is probably the case that without his peremptorily contrarian temperament, which put him so regularly at odds with major figures of his day, Bentley might never have teased out the contradictions and complexities of playwrights he admired as well as the ones he didn’t.

He lionized Pirandello, for instance, and championed Ibsen, but few of their admirers have ever written so frankly or comprehensively about those dramatists’ shortcomings as well. Bentley brought a similarly rounded view to writers that interested him but he mostly didn’t care for, including Miller and O’Neill.

Nothing demonstrates what might be thought of as Bentley’s critical integrity so well as his dealings with Brecht. This was the one figure, apart from Shaw, that Bentley most admired and on which he pinned his hopes for the future of the theatre, and the admiration was reportedly mutual. But when Brecht rather hamfistedly insisted on Bentley’s political fealty to his brand of Eastern bloc Communism, Bentley bluntly declined. As an anti-Soviet leftist with seemingly equal disdain for hardline Marxists and softheaded Western liberals, Bentley quite literally made enemies right and left—but mostly left.

The occasion for our meeting was the aftermath of a centennial celebration at Town Hall, organized by soprano Karyn Levitt, who recently released the album Eric Bentley’s Brecht-Eisler Songbook. Bentley had watched the event—which was hosted by a former mentee and housemate, Michael Riedel (yes, that Michael Riedel), and featured tributes from various luminaries (including Kushner)—from home via livestream. Below are excerts from our conversation.

ROB WEINERT-KENDT: I can’t help noticing The New Republic there on your desk. Do you still read it?

ERIC BENTLEY: It’s a good question, because they’ve been coming free, and they wrote me the other day wondering whether I was going to order a subscription. I haven’t made up my mind yet. It’s rather interesting, but without any identity. I don’t know what they stand for. So I think I won’t be subscribing to it immediately, but we’ll see how they do. It’s had a history; I was the drama critic there long ago, in the ’50s, and then Robert Brustein took over and held it for about 20 or 30 years.

I’d like to go back even further to how and when you caught the theatre bug. Was it in Bolton, in Northern England, where you grew up?

Acting Shakespeare in high school was the main thing. I went to a local grammar school, and they featured every spring a Shakespeare production directed by one of the faculty. Incidentally I played Macbeth, and Ian McKellen played the same part later at the same school. He told me once, “I should hate you.” I said, “Why?” He said, “Because the headmaster held you up as a model to us all, and we were made to feel we could never be as good.”

Being from the North of England, did you feel like an outsider at Oxford?

I toiled very hard to get scholarships, because my parents couldn’t afford to send me to university. A lot of Oxford I wasn’t impressed by, but the great experience was with C.S. Lewis. He wasn’t well known then, and he hadn’t written all these religious things; I knew his religious views, but he never imposed them on me. So there was not a religious thing. It was just that he made me more aware of everything. I was pretentious, as I was bound to be; with my uneducated background, I tried too hard. I used long words that I didn’t always understand. I would read my paper aloud to him and he would sit there with his pipe. When I paused, he said, “That makes my head swim.” He asked me the meaning of a word, and I said, “I don’t quite understand the word, but I thought you would, sir.” He laughed. I said, “Was there anything good about it?” He said, “Oh, yes, most of the passages were quite good; it was just here and there.” I said, “Would you name a good passage?” Looking over his notes, he gave me an awareness of when my prose was best, and I said, “Well, that’s just me talking.” He said, “You should talk on, and not read these other critics.” He gave me the confidence in myself just to be natural.

Did you have models in mind for the kind of critic you would become?

That was later, when I came to America, as a graduate student to Yale. That was the period in which I did wide reading and discovered who I was most interested in. Shaw developed as my main interest for a while. He and Brecht are the only ones I’ve written whole books about. I never met Shaw; I was on the point of meeting him when he discouraged me from visiting, because he said I would be disappointed; he was just an old man. He said I wouldn’t meet the author of Man and Superman; I would meet an old man. I should have gone anyway.

So you didn’t necessarily grow up wanting to be a critic?

I wasn’t sure in my youth. I knew I was ambitious, but I didn’t know what I was ambitious for. At first I was inclined to be a musician. I played the piano reasonably well, and my teacher was very helpful and proud of me. That was what I was intending when I went to Oxford; I was thinking my career’s in music. Then I realized that unless you’re one of a half dozen great soloists, there’s no career in piano playing. I lost interest in being the great pianist, and gradually by the time I was at Yale, if not before, my allegiance had switched to drama.

My first book, the thesis from Yale, was not yet about drama; it was on the history of ideas. I’d read widely in philosophy and that kind of thing, and in the book on the history of ideas, Shaw popped up, and then I realized I was interested in him independently because he was a dramatist. He was the person who really switched me to drama. I realized from him, also, that you didn’t have to be frivolous to be interested in theatre; I could retain the seriousness. So I ended up writing a book on him, and that led to books on drama. But I still wasn’t clear where I wanted to go. I thought it might be directing. I did some directing of theatre. I didn’t see myself as a writer; I thought I would be a director. I did some, but I left it on a dramatic occasion which you might want me to speak of.

Please do.

I was directing my version of Brecht’s Good Woman of Setzuan in the ’50s, with Uta Hagen as the star. It was on 12th Street, where the Phoenix Theatre was. I had an experience with an actor, Albert Salmi, I could never forget. I couldn’t control him, so I retired from professional directing. My self-criticism was: If I can’t control my actors, I can’t be a director.

What was the problem with him?

I felt he was going to attack me, and my friends thought I was fantasizing. Later it turned out that he killed his wife and killed himself a few years later, which I read in the Times. My feeling that there was great violence directed at me; looking back, I see that I was right. I still should have mastered it, but for a young director, I was overwhelmed, and I never directed professionally again.

Is that why, unlike your colleagues Kenneth Tynan and Robert Brustein, you never helped found a theatre?

Well, the people you mention were the next generation. Bob Brustein says that I was responsible for effecting the same change in his life that I effected in my own—he began as a scholar, but under my influence, wanted to be the critic to succeed me, which he did, at The New Republic.

But he also founded a few theatres. Did you ever have that ambition?

Yes, I did. Where my pupil succeeded in two places, at Yale and Harvard, I failed at Columbia. There were a number of reasons why Columbia didn’t develop theatre. I first accepted a post at Columbia in order to be head of their coming theatre—which never came and still hasn’t come. They were going to tear down, on Amsterdam Ave., buildings which are still standing—the Ludlow post office, for one—and a new arts center was to be built, and I was to be the head of the theatrical section. The arts center was to contain two theatres, and I was to be in charge of one, the dramatic; the other one was music.

That never happened, for a number of reasons not connected with me. The main reason at the time was that the man that I owed my Columbia job to, and a great deal else, was Jacques Barzun, and he didn’t believe in developing a theatre. He said, “We’ll make you the head of the drama section, but I don’t want you to train for the theatre. There are plenty of schools in New York that do that, and Columbia will just be interested in training the leaders for the local arts centers.” So I gave up the part of my job that was to create the new theatre, and then a series of things happened which have only remotely to do with me. A student revolt meant Columbia had no money to proceed for a number of years; they’re okay now, with a huge new campus, but that’s all generations younger.

I’ve often heard the idea that a critic shouldn’t just review a show, then another, but should write with an ideal theatre in mind. Did you?

Yes, and I hoped that the Brechtian theatre would be that. But it wasn’t, for evident reasons; it was political, and it died with the death of a whole country, East Germany. So my interest in Brecht was connected with my idea of a better theatre, and not just for his plays; that looks pretty unreal now. I asked for a replacement of Broadway by another type of theatre, and I was ignoring the reigning economic facts.

Socialism introduced the idea that the state might create this possible theatre, and a woman who was my mother-in-law, namely Hallie Flanagan, in the ’30s, with the Federal Theatre, came the nearest to realizing this idea. She could open a play in 10 cities at one time on federal money. That was the opportunity that the ’30s offered; it was all the New Deal and Roosevelt.

Some would say the resident theatre movement of the 1960s, which also got a boost from government funding, was a less centralized iteration of the Federal Theatre dream. Your book In Search of Theatre had you traipsing around Europe seeing plays; did you ever do the same around the U.S.?

Yes, I did. I was interested in Herbert Blau at the Actors Workshop in San Francisco; he did some of my Brecht adaptations. I thought that the regional theatre held out a hope, whereas in fact it turned out to do warmed-over Broadway, or intentional Broadway, and to be middlebrow rather than highbrow, as I wanted. I hoped the Brecht plays would connect, and encourage the idea of a new theatre. But you know the history of America—and the history of Germany.

Also in the ’60s and ’70s there emerged a theatre of protest, an avant-garde. Did that give you hope at the time?

Yes, and I wrote one book about it, which was called Theatre of War. I had great hopes of the left-wing producing the new theatre in the ’60s. I was seeing yesterday on the television Peter, Paul & Mary. That looks so far away—the expectation that songs would change America.

Did you share that dream?

Oh, yes. I lost my job at Columbia because I sided with the students. I hope you don’t know the play Charles Marowitz wrote about me. It’s been published. I asked him for an alteration, at least in one passage, because he not only described Brecht as a fraud, but described me as a fraud, in that I had threatened to leave Columbia if such and such didn’t happen, and I held onto my well paid job. In fact, I didn’t; I did resign. I lost my well paid job. So I asked him to change that passage; I couldn’t ask him to change his whole play.

Since you introduced him to the English-speaking world, Brecht’s reputation that has fluctuated, particularly after John Fuegi’s book Brecht and Company, which alleged that he stole the work of his mostly female assistants. Did you follow that controversy?

I was deeply involved with Fuegi. At the University of Maryland, he’d given me a job when I left Columbia. I read his book in manuscript, and I corrected many facts which he mostly acknowledged and made the corrections. But although I got along with him, and owed my job to him, I didn’t agree with his denunciations of Brecht, let alone subsequent denunciations of me—not from him, but from people who’ve read the book. Meanwhile, I was quarreling with the Brecht estate. So I was caught. I didn’t like to side with either side in that debate. I haven’t seen Fuegi in recent years. I gather he’s making films on other subjects. But I never joined in the denunciations of his book, because of my relationship with him, but I’ve also not praised it.

But the central thesis—that Brecht was a plagiarist—you would reject?

Yes, I would reject that. He quotes me in the book as being on his side, and saying that I was a witness of Elisabeth Hauptmann actually changing a Brecht text and writing it. The truth of that story, which I tell in my Brecht memoir, is that Elisabeth Hauptmann, who lived here on Riverside Dr., indeed devoted her life to Brecht. I worked with her, and it was clear to me that she didn’t write; she made no claims. She would say, when correcting my English version, “What Brecht meant was.” She would never say, “I wrote it.” Which she would have.

In The Playwright as Thinker, which was written after World War II, you dispatched with the notion that the previous decades had been a good era for playwriting. Since then there have been many claims about various “golden ages.” Is there any era you think of as a golden age for the theatre?

No, absolutely not. The names I chose, the great names—they mostly never had an era until they were dead. Ibsen was universally rejected as indecent, except by Shaw and other individuals. The ones that ruled the theatre were like Somerset Maugham, who once described himself as the best of second-rate novelists; I thought that was a very shrewd and self-critical remark. To me the same was true of Arthur Miller: He wasn’t what he hoped to be and what his admirers thought he was. That was my doubt, under all the political differences that I expressed.

He never forgave me. I never met Miller, I don’t think, except in an elevator at the United Nations, where we were both invited to a lunch by Dag Hammerskjold. I saw Miller and I said, “I think I should introduce myself; I’m Eric Bentley.” I stuck out my hand and he refused to take it. I read his memoir, Timebends, where he says that I maintain that Kazan wrote his plays. I never maintained anything of the kind. I said that his contribution as director made him part author.

Your criticisms of Miller remind me of your criticisms of O’Neill—that both very self-consciously wanted to be the Great American Playwright and mostly fell short, though O’Neill eventually did write Long Day’s Journey Into Night.

Which was written after I wrote my most critical pieces of him. He is unique in so many ways: He was born on Broadway but he rejected Broadway. I came to be an admirer not only of the one play but of several; I think the ones he threw away were probably very good. He was fighting his own demons.

But Miller? No reevaluation there?

Well, he’s better than I said, probably, because I was involved in a polemic. When I look back at some of my criticisms, I see that I was more of a Brechtian than I thought; I was wanting him to take over Broadway. Theatre criticism is bound to be very enveloped in the current controversies, both about theatre and about politics. But I don’t mind, because we’re all subject to that.

My model, of course, as a critic was Shaw. We both wrote for a public that would never see the plays, mostly, for a weekly that circulated all over the country but whose readers were not lodged in the theatre capital. So Shaw wrote for a public that was acquainted with what was going on in the world, including what was going on in drama, but he never accepted the West End of London. His own plays are now done as classics by regional theatre, but if you look back at the 1890s, you’ll find that some of them opened on a special performance on Sunday night, one night only. He published them because they weren’t being staged.

So the history of theatre is this double thing: the history of the Broadway theatre and the West End theatre, and the literary history of the great writers who wrote for theatre. Like Strindberg, who’s still just a name—he’s never had a long Broadway run, I don’t think, and he was neglected in his own time. In his later years, he felt totally ignored.

So would you say that art happens in the commercial or popular theatre almost in spite of itself, or by accident?

Yes. Or, a play like Pygmalion is so funny and amusing that it is acceptable as a lowbrow play, but it is actually, if you use the term, a highbrow play about life in general and has some quite deep thought in it. This duality didn’t work for Shaw in his own time, at least not when he was young. About one of his early plays, I think it was You Never Can Tell, he wrote that he noticed that when there was a lot of eating onstage, the play was successful, so he put a lot of eating in his next play.

I’ve read that Brecht loved musicals, but they seem not to have interested you much.

I’ve been resistant to the musical, because originally I was very fond of operetta, particularly from Paris or Vienna or Eastern Europe. But musicals have become operetta, and I respect that. I now respect more than I did then Frank Loesser’s shows; I think his music is just marvelously appropriate. He deserves the credit that Arthur Miller gets.

I liked the musical theatre of the 1920s and 1930s, but I was resistant to Rodgers and Hammerstein because of their sentimental liberalism; I had a political objection. I respect Rodgers’ talent for melody, which even great musicians, like Leonard Bernstein, envied. But when it comes to Leonard Bernstein, that’s in the class of opera. I’m very fond of the lighter side of the opera, and I regard Offenbach as one of the greatest, practically up there with Mozart.

Someone needs to write The Composer as Thinker.

Well, there’s an art to light music, so-called, which sometimes isn’t so light. And Offenbach was very aware of this. His last work, The Tales of Hoffman, was no longer in the operetta category; it was serious opera. But for me there’s no real distinction. I see the difficulty he was in with the opera houses; they didn’t know how to classify him. But classification is unimportant to me. If I write a play and call it a tragedy, but it will only be produced if it’s called a comedy, I’ll call it a comedy, because I think the category is unimportant.

That’s interesting, because as a critic, you were always careful to say that while categories and labels shouldn’t be taken too seriously, you did make distinctions—your whole whole critical project, in part, was to think quite systematically about the theatre.

The way theatre is taught in the colleges, we’re all supposed to know what words like realism mean, and we don’t. We have to look into it. I think a given critic has to make clear to his readers how he uses the word realism, because it varies so much. Brecht was very insistent on being described as a realist, but many people think of him as the opposite of realism, so the terms have to be clarified. We have to give to the great writers the right to use the word as they want; Brecht was prepared to defend his version of realism.

I read somewhere that your mother was a Baptist. Did you have a strict religious upbringing?

Yes, my family were devoutly Baptist, especially my mother, and she planned that I would be a Baptist missionary in Africa or the Far East. So it was a great blow to her when, in my adolescence, I read modern authors and lost my faith. I didn’t lose my faith totally ever, but in my college years I announced my leaving—announced to myself, at any rate—the Baptist church and I joined the Society of Friends, which I never actually left. On the wall in my kitchen is a Quaker motto, “War is the not the answer.” That is still my comment on current politics; it grows more relevant all the time. And it’s what I retain, consciously, of Christianity. I think there is a Christian spirit, even if you don’t believe in God. I’m one of the many enthusiasts of the present Pope; I think to dismiss his faith in God as just one of his illusions is shallow and not fair. The word atheism can be as much an illusion as the word God.

So I’ve gone through a development from Baptist Christianity to Quakerism to unbelief to leftism, semi-Marxism. Today I would read with respect books like God Is Not Great—I see the point of that—but I don’t think it goes far enough. I would want to discuss the different definitions of the word God, some of which I feel we should accept.

The Encyclopedia Britannica entry about you says your work “stems from a belief that art must rescue humanity from meaninglessness.” I don’t think that’s a quote.

No, it’s certainly not.

But does that sound right?

I don’t find the world meaningless without art, but I think my idea of meaning, or yours, comes from literature as much as, or more than, theological works. On the other hand, the argument we might have about God and the different definitions is not just a literary argument. I think that Brecht was not as irreligious as he thought, but I would have to argue that.

In his beliefs or his practice?

Mother Courage has very Christian elements; two of her offspring are Christian martyrs. I think, on the whole, the discussion has been superficial, both on the Christian side and on the atheist side—too defensive of this or that. Skepticism is necessary, but skepticism applies to atheism, and to us all. What are we not skeptical of?

Brecht didn’t take over Broadway, obviously, but we’re still arguing about theatre in America—a few of us, at least. Is that enough to be hopeful?

Anybody who writes a real play that is a performable thing is creating present theatre, even if they refuse to perform it. Woyzeck took a century before it was performed.

So the material conditions of our present theatre don’t necessarily diagnose the health of our drama.

Yes. But it’s an immensely complicated subject. The history of opera, for instance: It’s very hard to say to what extent the great composers kept it going, and to what extent it would have existed without them, as a courtly exercise, and as a place for rich people to go.

Right. There’s a lot of art from the so-called great periods that we’d never want to sit through; there are periods from which no “classics” have emerged but people still went to theatre.

And the opposite is true. Handel’s operas were discarded, but when they’re revived now, I find they’re very good. History is quite confusing, like theology.

One reason I and others return to your writing is that it’s the opposite of confusing. The concepts remain challenging, certainly, but the language is accessible.

To a degree, the system brings this about. On the one hand, there’s journalism, writing for the newspapers, and on the other hand, there’s writing for learned journals. But there’s a lot of room in the middle.

I know a lot of talented people in that space—indeed, I think we publish a number of them.

They should remain in between and not settle for one or the other.