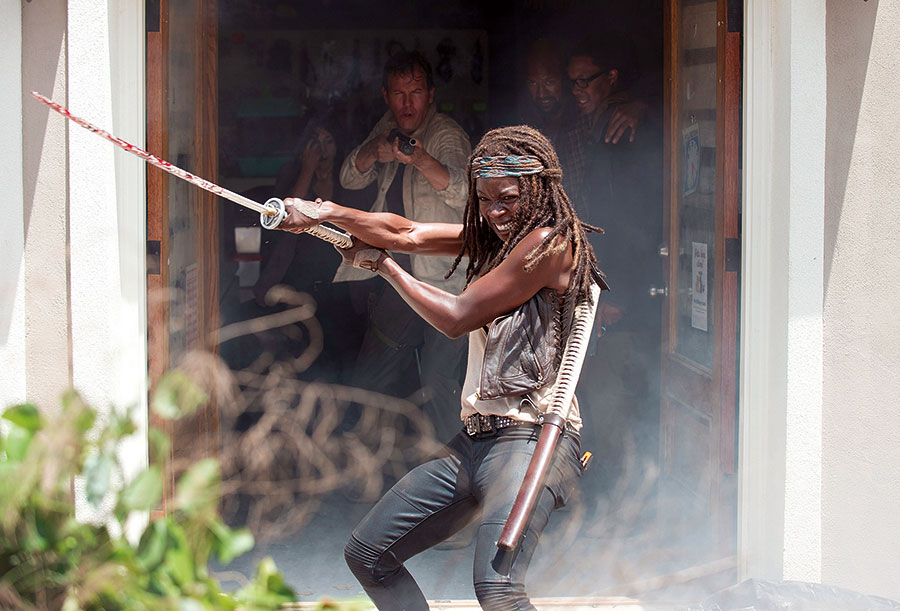

In 2012, the world met Danai Gurira. That was the year she first appeared as Michonne, the dreadlocked, katana-wielding zombie killer, arguably the most iconic character on AMC’s “The Walking Dead.” What most of that global audience probably didn’t know was that as she was training for the physically demanding role, Gurira was also making a splash as a playwright. That same year her third play, The Convert, was at Center Theatre Group in Los Angeles. “I was like rehearsing with the sword in the basement of the Kirk Douglas,” she recalled.

Adam Immerwahr, who was the associate director for that production and is now artistic director of Theater J in Washington, D.C., has fond memories from that time. “I would be talking about a moment from the play and she would be practicing sword moves toward my neck with a butter knife,” he said over email.

“It was perfect synchronicity, but it was so bizarre. That was when the worlds were merging,” Gurira recalled, chuckling. They’ve been merged ever since—or at least they’ve been running on parallel tracks. For the actor/playwright, 2015 began with the world premiere of her newest play, Familiar, at Yale Repertory Theatre in New Haven, Conn. Then in the late spring, Gurira flew to Atlanta to film season six of “The Walking Dead” (when asked if her character is still alive, she deadpanned, “Who knows?”).

Meanwhile she was back and forth between the Big Peach and the Big Apple, where she was preparing for last fall’s Public Theater run of her play Eclipsed—starring Oscar winner Lupita Nyong’o, which would later be announced for a Broadway transfer—and where she was further developing Familiar for its upcoming stint at Playwrights Horizons; both start previews next month (Eclipsed Feb. 23, Familiar Feb. 12). As if that weren’t enough, Gurira’s talent-nurturing organization, Almasi Arts Alliance, achieved 501(c)3 status, and she made her annual trip to Zimbabwe, where she was partly raised.

Michonne may be able to slice a zombie’s neck with graceful finesse, but Gurira is clearly superhuman on a different level. When we spoke in late December, just before the holidays, she was in New York City for four days to deliver a new draft of Familiar to Playwrights Horizons; she would soon fly back to her home in L.A. “I’m getting on a plane on Monday and I’m staying put for a month. It’s going to be glorious,” she said over a long lunch of niçoise salads and truffle fries at Les Halles in the Financial District. The brasserie happens to be down the street from Gurira’s first New York apartment; she moved in a week before 9/11, she noted as we walked to the restaurant.

The two worlds she now inhabits, acting and playwriting, were once literally merged. Her first play was about African and African-American women with HIV/AIDS, In the Continuum, which she created and performed with Nikkole Salter; that show toured for three years and earned both women Obies and Helen Hayes Awards. But Gurira’s second play, Eclipsed, which began its life at D.C.’s Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company in 2009, didn’t feature her in the cast; nor did her third play, The Convert, which has had multiple productions across the country (and was printed in full in AT Sept. ’13). It’s currently running through Feb. 28 at Central Square Theater in Cambridge, Mass.

She didn’t stop acting onstage; she made her Broadway debut in 2009 as Martha Pentecost in the Bartlett Sher–directed revival of August Wilson’s Joe Turner’s Come and Gone. But if her writing and acting careers had begun to diverge—she soon nabbed a recurring role on HBO’s “Treme”—neither one took precedence.

“She’s a powerhouse,” raved James Bundy, artistic director of Yale Rep, which has produced three of Gurira’s plays. He compares her to such multitalented artists as Anna Deavere Smith, Taylor Mac, and Tracy Letts. “She’s got a really significant acting career and a really significant playwriting career. How many theatre artists can we say that about today? Who knows what else Danai can do? I don’t. She could probably run a major NGO or be a successful politician.”

Gurira is not prone to dismiss her zombie-filled day job as mere pulpy fun. In fact, she said she became interested in “The Walking Dead” because it reminded her of Eclipsed, which follows five women, three of them sex slaves, during Liberia’s second civil war. Indeed, when Gurira’s “Walking Dead” castmates saw Eclipsed during its Public Theater engagement, she said “they were like, ‘It’s like our show!’” Both, she explained, are set in extreme circumstances where “the world has become something else, and who are you in it?” The kind of place, in other words, where “women choose to become their own weapon, which is exactly what Michonne did, and it’s exactly what a couple of women in the play do.”

In person, though she doesn’t boast Michonne’s dreadlocks, Gurira is at first a formidable presence, with an athletic build and large, piercing eyes. The word “fierce” was used by many of her colleagues who were interviewed for this story. But listening to her speak—in large, poetic paragraphs—with an aura of ease and warmth, it’s easy to see why so many collaborators employ many other positive adjectives as well.

“I love working with her,” said Liesl Tommy, who directed Eclipsed in its world premiere at Woolly Mammoth, and has stayed with it from Yale Rep to the Public, and now on Broadway. “We’re both women from Southern Africa, there’s a lot of cultural similarities,” said Tommy, who hails from South Africa. “It was gold to find a collaborator that you had so much connection with. Both of us have felt so many African women’s stories were just completely marginalized, if not invisible, in the American theatre.”

Indeed, Gurira’s bio consistently contains the line, a kind of mission statement: “All her works explore the subjective African voice.” That was true of In the Continuum, and it’s certainly true of Eclipsed and The Convert. The latter play follows a Shona girl named Jekesai in colonial-era Zimbabwe (then called Rhodesia) as she struggles between her Shona traditions and her newfound Christian faith. Gurira’s newest play, Familiar, may be set in the U.S., but it too centers on “the subjective African voice,” as its main event is the wedding of the oldest daughter in a Zimbabwean-American family.

But despite her stated agenda, Gurira isn’t comfortable summing up her plays’ politics. “I want to hit on issues and experiences that African women have. And people ask, ‘Are you a political writer?’ I’m like, ‘I don’t know!’ I’m just telling truthful stories about true circumstances.”

She’s found a kindred spirit in Emily Mann, artistic director of Princeton, N.J.’s McCarter Theatre Center, who directed The Convert’s world premiere; Eclipsed was also developed at the theatre. “She has not only the passion and understanding of actors and character, but she has big stories to tell, important stories to tell, that matter in a big way. So she’s just my kind of girl, you know?” said Mann, who’s no stranger to political theatre, with a laugh. “She’s scary talented.”

Not unlike Mann, in fact, Gurira approaches playwriting like a documentarian. For Eclipsed, her inspiration was a photo of Black Diamond, a female Liberian freedom fighter, in a New York Times article. That image prompted curiosity about Liberia’s 14-year civil wars, which left more than 200,000 people dead, and a 2007 trip to Liberia (funded by a grant from Theatre Communications Group). There Gurira interviewed more than 30 women—women who had been raped, whose daughters had been taken by rebel fighters and turned into sex slaves. She also spoke to female peace activists who were instrumental in ending the violence. The names of the women in Eclipsed—Helena, Maima, Rita, Bessie—come from people Gurira met in her travels (a fifth character is unnamed).

When, for The Convert, Gurira wanted to write an African version of Shaw’s Pygmalion, another TCG grant funded research trips to Zimbabwe. “I actually function in a very academic way,” Gurira explained. She’ll “look at like facts, figures, issues…and from there I want to pull back and say, ‘What’s a personal story in that stat or in that dynamic or in that moment?’ I feel like ultimately a narrative tells me what it is, and it’s my job to keep submitting to it until I really hear it, until I’m a worthy vessel.”

She calls her plays “fiction nonfiction.” So it’s no surprise that as well as being entertaining, they’re edifying, according to Pascale Armand, a member of the Eclipsed cast at Yale, at the Public, and on Broadway. She also played Jekesai in The Convert at McCarter.

After seeing Gurira’s plays, Armand said, “You can’t just say you didn’t know anymore. That’s not going to be anybody’s excuse after they see Eclipsed. They can’t say, ‘Oh, I had no idea what was going on in Liberia and that women and children have been raped for 14 years, in this war propagated by men.’ I feel like Eclipsed will be a call to action.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given her meticulous approach, Gurira is the child of Zimbabwean academics. She was born in Grinnell, Iowa, the fourth and youngest child of a chemistry professor and a university librarian. Her parents had moved to the United States in the 1960s on academic scholarships and studied at Pennsylvania State University. In 1983, when Gurira was 5 years old and Zimbabwe’s independent democracy was only 3 years old, the family moved to the nation’s capital, Harare. “Probably the cities I know best in the world are New York City and Harare,” said Gurira. “I can get to Harare, and I know exactly how to get anywhere. I can get in a car and go, ‘Turn left, turn right, there over the hill.’”

Gurira’s own journey into the dramatic arts was a bumpy one, filled with stops and starts and doubts. Though there are very few consistently producing professional theatres in Zimbabwe, Gurira studied the classics in high school. “We would do productions of Hamlet and, you know, I was in an all-girls school. I played Laertes. It was fun!” she recalled fondly. A formative moment came in her senior year, when childhood friend Chipo Chung (most recently seen in NBC’s “A.D.: The Bible Continues”) was directing a school production of for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf. Gurira played the Lady in Red, and was given the monologue “a nite with beau willie brown,” which ends with Beau throwing his two children out of a window.

That was when everything shifted, Gurira remembered. “You kind of realize that when you do this thing, it kind of works. That monologue experience was when that happened for me. It becomes clear what your passion is; it becomes clear, this is where you are entirely immersed and engaged, and it feels—there’s something effortless in that immersion.”

Still, Gurira hesitated. She had a passionate activist streak—she recalled that her parents’ house had a signed photo of Martin Luther King Jr. on the wall—so she moved back to the U.S. to attend Macalester College in Minnesota and major in psychology. “I wanted to be engaged in social change,” she said, “and I didn’t know how being an actor full time would allow for that.”

But when she studied abroad in South Africa junior year, soon after apartheid ended, she met artists who were also activists, including actor John Kani and playwright Winston Ntshona. Here were individuals who had used art to shed light to the wider world on the racial injustices happening in their country.

“They were doing it in seriously dangerous circumstances,” Gurira said. “John Kani was talking about how they were doing Sizwe Banzi Is Dead or Woza Albert! and they didn’t know if when they stepped outside the door, the police would be waiting for them. Which sometimes they were.” She walked away from that contact, she said, with “no excuse not to know that I can use this craft for the things I care about.”

With a small smile, she mused, “It’s funny—every time I tried to run away from the craft, it would always catch up with me and hook me in.”

RITA: Well good. GOOD. They scare of us, maybe we can actually get them to the point where things change and they stop acting like BEASTS, trying to treat us like we village girls they rob from de bush.

In 2001, Gurira began her first year at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts graduate acting program. Hyper aware of her dual identity as both a Zimbabwean and an American (or a “Zimerican,” as she calls herself), she began to notice not only a significant lack of work for African and African-American women but also that mainstream America primarily saw Africa as a statistic, as a culturally homogeneous continent full of nothing but war, HIV, and underdeveloped villages.

“No other country, no other continent would be dealt with like this,” she said, frustration evident in her voice. “Like a monolith—like it’s one little village, like literally they all speak the same language or they all ‘click.’ It developed a rage in me.” She honed that rage into a mission: “If I start to bring a voice to the fore where you realized the complexities of being African and a human being, and I bring that story forward, those other stories hopefully become a little less acceptable.”

She pursued that goal with a calculated ferocity, according to Nikkole Salter, who studied with Gurira at NYU. “She had to not only gain visibility but have the platform to uncover her humanity,” Salter said. “So she was definitely about becoming a star, definitely about being among the most influential voices in the biggest media outlets that she could find, because her mission was to make African women as visible as possible.”

In Familiar, Gurira has brought that mission home in a new way, telling the story of first-generation African immigrants to the U.S. The play takes place at the rehearsal dinner for the wedding of Tendikayi, the eldest child in a family of educated Zimbabweans who immigrated to the United States in their 20s and now live in a wealthy Minnesota suburb. As with her other plays, the impulse came from realizing that stories like this had not been told onstage.

“People don’t really know about Africans in America,” said Gurira. “They don’t realize Africans are the most educated immigrant group, which is crazy! No one would believe it, but it’s true.”

While she is careful to point out that the family in the play is similar to her own family—four siblings, the Midwestern background—it is not the Guriras. But it does pose the same questions about assimilation and identity that Gurira faced.

“I grew up with a mother with an African accent who was great at making apple pies and cinnamon rolls and lasagna, because she was in the Midwest for 25 years,” Gurira said. “All the complexities that come with being the child of immigrants, and specifically African, and what your identity means, what assimilation means, what association means—that is definitely what the play is exploring.”

It’s Gurira’s version of an American living-room drama, in short, with both sad and comic elements. But it’s no less ambitious than the plays she’s set in Africa. Said Rebecca Taichman, who directed Familiar at Yale and will helm the upcoming Playwrights Horizons production, “She’s asking huge, mythic, important questions in extremely theatrical ways. She melds the quotidian with the epic, the life of a family in a living room.”

Gurira is not just writing for Americans who want to learn about African cultures, of course; she’s also writing for Africans hungry to see authentic representations of themselves onstage. And her attention to historical detail has paid off; all of her plays have been produced in Africa to acclaim and full houses. “It has to be something that works on the continent—it can’t just work here. Otherwise it’s failed,” she said bluntly.

Immerwahr recalled the reception of The Convert’s 2013 Harare production, which he directed. Despite periodic power outages during the run, he said, audiences were riveted; in Zimbabwe, it’s rare for a piece of art to explore the country’s history. In one scene, two Zimbabweans who had converted to Christianity, Chilford and Chancellor, debate whether the native Shona people will rise up against the British colonials.

“Chilford’s going, ‘No no no they won’t.’ In America audiences were listening to that going, ‘Oh, there’s people called the Shona and they might uprise.’ In Zimbabwe, everyone’s listening to it going, ‘Oh, my God, Chilford, what an idiot man, of course they will uprise!’ It was a fascinating scene in America, but it was a hilarious scene in Zimbabwe,” Immerwahr remembered, laughing.

The African staging of The Convert was produced by Almasi Collaborative Arts, the not-for-profit Gurira cofounded in 2011 with Zimbabwean director Patience Gamu Tawengwa. Its mission is to professionalize the Zimbabwean performing arts by training artists, facilitating cultural exchange, and producing work. In its four years of existence, Almasi Collaborative Arts, and its American branch, Almasi Arts Alliance, have not only produced The Convert in Harare; they’ve also held regular readings and given grants and fellowships to Zimbabwean theatre artists to study at American institutions and be mentored by American professional artists.

Gurira has still grander plans. “Ultimately I’d love it to be something like a Yale School of Drama that also has a Yale Repertory attached, which I don’t think really exists [in Africa]. South Africa has some institutions, but largely that doesn’t exist on the continent yet.”

Her plans for her own career are no less bold, though apart from “The Walking Dead” they seem to be focused more on writing than performing. She’s currently working on an HBO pilot and crafting another play about Zimbabwe that may, with The Convert and Familiar, become a trilogy or even a quadrology spanning the history of the country. She was also recently cast as Afeni Shakur, mother of the late rapper Tupac, in the upcoming biopic All Eyez on Me*, though the question remains: Will she ever step back into her own plays onstage?

“It’s not necessary,” she said. “I want to see other people fly. Let’s find five amazing actresses and give them an opportunity to do their thing, which unfortunately doesn’t happen very often for women of African descent. A big part of my creative mandate is to create those opportunities.”

In a field currently struggling with the lack of women and people of color in the pipeline—not only on Broadway but in Hollywood as well—Gurira is creating her own global pipeline.

“I think it’s an exciting moment to be alive, to be a woman, and I think we should continue to push, ’cause it’s just time to,” she said, resolve in her voice. “It’s time to keep pushing forward and making sure we exact as much change as possible. It’s a time where we can make this world very, very different for our daughters.”