“When you’re in town, wearing some kind of uniform is helpful…at the very least you should wear a suit and carry a briefcase and a cell phone.”

Thus spake Mark Rylance at the 2008 Tony Awards upon receiving a trophy for his performance in Boeing-Boeing. The crowd was baffled by this impromptu fashion advice from the British actor, already well known for running Shakespeare’s Globe in London from 1995 to 2005, and for scattered appearances on U.S. stages and in films, though the much-performed French farce was his Broadway debut.

He went on, amid titters and bewilderment: “Otherwise, it might appear that you don’t know what you’re doing, that you’re just wandering the Earth, no particular reason for being here, no particular place to go.”

Rylance knew what he was doing: In place of a traditional acceptance speech, he was delivering a full poem by Louis Jenkins, a Minnesota poet Rylance had admired for years. In fact, Rylance had been reciting Jenkins’s poetry for years at dinner parties and events, at times using a Midwestern accent, as he did on Tony night. The accent and the affinity, it turns out, are not borrowed affectations: Rylance, though born in England, spent his youth and adolescence in the U.S., first in Connecticut and then, crucially, in icy Wisconsin.

That same year, Rylance assembled a workshop production of a play in which two ice fishermen sat on a frozen Minnesota lake and spoke Jenkins’s prose poems back and forth to each other; the poet’s writing, rooted in everyday observations with a hint of whimsy and a touch of sorrow, had always sounded to him like dialogue. He called the show Nice Fish, after a poem featured in the show.

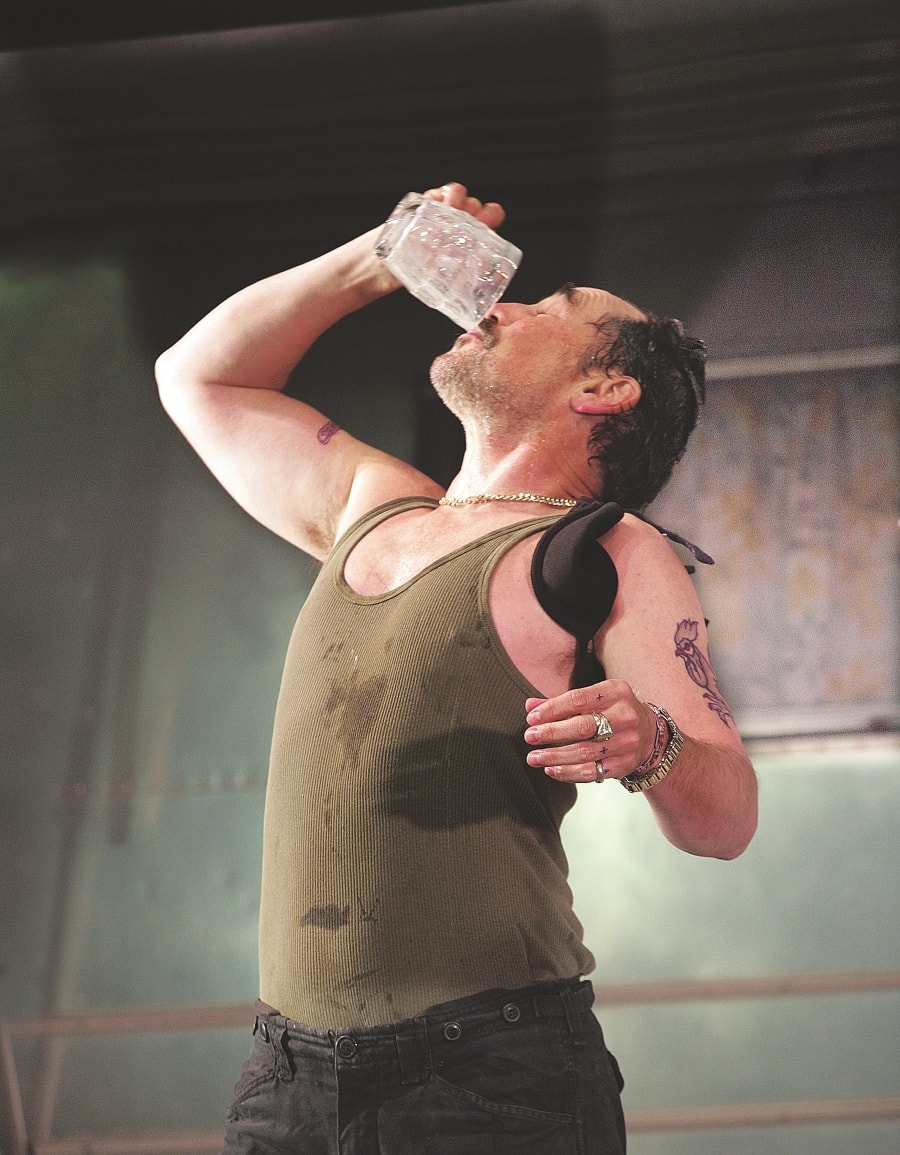

By 2011, when he accepted his second Tony for Jerusalem with another Jenkins recitation, an expanded, full-length version of Nice Fish was already underway. A three-act version had its world premiere in 2013 at the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis, with a script that was equal parts Jenkins and Rylance. In it, two old friends, Ron and Erik, go ice fishing together in Minnesota on the last day of winter when the ice has begun to melt. Encountering a mix of earthly and surreal elements, the fishermen are visited by a DNR (Department of Natural Resources) officer and two strangers.

The Guthrie production was instructive for Rylance, he said recently. “I added too much,” he conceded. The play would be more powerful, he resolved, if he shaved off the majority of his own dialogue, leaving only essential connective tissue between the poems. A reworked Nice Fish premieres in a coproduction at American Repertory Theater in Cambridge, Mass., beginning Jan. 17, and at St. Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn beginning Feb. 14. His wife, Claire van Kampen, directs.

Rylance’s American background has never been a secret, but in Nice Fish it’s front and center in a new way. It isn’t just Jenkins’s perceptiveness about human nature that appeals to the actor; it’s his spot-on depiction of a Midwest he remembers—a world of winter sports and stoicism, where nature has a larger-than-life presence that can be both comforting and forbidding. Between preparing for the East Coast debut of Nice Fish, starring in the West End run of the Shakespeare’s Globe production of Farinelli and the King (written by van Kampen), doing press for the film Bridge of Spies, and sitting down to write a new play, the now three-time Tony winner and two-time Olivier winner took some time to talk from his home in London about Jenkins’s work, his memories of winters back home, and why, for a writer, a frozen lake is fertile ground.

The cold climate of a Minnesota winter sets the tone for the entire play. What do you remember about your childhood winters in Wisconsin? Did you enjoy that time of year?

It was very cold. My father had a bad history with cars, and in the bad weather it was a serious problem if you had a car that could potentially break down. My brother used to just hibernate at a certain point in autumn when it got too cold to play football, so it was me out in the snow and on the ice.

There was a beautiful field behind our house, which was on the edge of the suburbs of Milwaukee, and that field used to freeze and we’d play ice hockey on the frozen lake. It was fiercely cold, but I miss it very much here in England. The spring is beautiful in England, but in the north Midwest, spring is so dramatic—it’s been so long since one’s seen green, and suddenly everything bursts into color.

I was speaking to a friend who grew up in a rural area of Minnesota where he regularly went ice fishing with male relatives. He said that each experience was a paradoxical mix of bonding and solitude. That seemed to fit Erik and Ron, the close friends who meet up for an ice fishing trip in Nice Fish.

Right—they come together but their experiences are solitary, and they have very different outlooks on life. Yes, it is primarily a bonding place for men out on the ice. I was interested in why men go out there. A lot of Louis’s writing has to do with hopes and failures around relationships with women, so that proved a good synchronicity.

On that note, tell me about Flo, the one female character in the play, who visits the men on the ice. In the Guthrie production, she was presented as an ancient goddess. What is her impact on the story?

It’s very different in the new version; that’s the part of the play that I’ve looked at most. I thought that the mythical reality that I had at the Guthrie was more than was needed. So I’ve taken that out. Now the two characters that Ron and Erik meet are a young woman, more like a daughter to them, and an elderly man, a spear fisherman.

So then the love story between Ron and Flo—as that changed now that she’s much younger?

Yeah, it’s not a love story anymore; he doesn’t have romantic feelings for her. The two guests in a way amplify the qualities that Ron and Erik already have. [The young woman] is very imaginative and in love with everything that’s possible, which is very much where Ron is interested. Wayne [the older visitor] has more to do with winter and everything that is limited and coming to an end, which is Erik’s territory. So the two guests challenge the fishermen, because they’re more extreme versions of what the fishermen are.

There’s an interesting contrast between Wayne, who’s a traditional spear fisherman, and Erik, a contemporary ice fisherman with the latest technology and equipment.

Yeah, when I went ice fishing, you were looking for an experience in the wilderness and the wild. But then there’s so much technology, with the radar and televisions—the technology is meant to help, but it distances them from their instincts. So Wayne is that voice: He’s a much older hunter and he talks about the original experiences of Ojibwe Indians [indigenous to Minnesota], fishing for their livelihood and not as a hobby.

Does Erik think something is missing from his life when he goes out on the ice that day?

I think both [Erik and Ron] think something is missing but they’re not sure what. They become more aware of that when they’re out there. They’re looking for something. The first poem of the play is about looking for something deep down that would swallow them whole if it had the chance. They’re looking for something more fulfilling than what’s in their life.

Was the impetus to create this play a love for Jenkins’s writing or an interest in depicting the Midwest in winter?

I think I first encountered the poems and realized [when I read them aloud] that people thought I was speaking my own thoughts. I realized that they had the potential to be dialogue. The idea of the play came after that. So the poems really led it. Also, Robert Bly’s introduction to Louis’s first book of poetry describes an adult voice and a child’s voice, that he could hear in the poetry as two voices in Louis—that gave me the idea of two men [one with a heavy disposition and the other lighthearted]. And then I had been ice fishing when I did Peer Gynt at the Guthrie.

So the first version was a workshop in 2008, which was just two fishermen speaking the poems for about 45 minutes. I wanted to enlarge the play, and Jez Butterworth suggested that I put the DNR man in it. But the new play is going to come back to the initial idea and have as little of my own writing and as much of Louis’s writing as possible.

I noticed that because Louis is an elderly man, there are a lot of poems about age, so the idea of the visitors being related to youth and age—that became more interesting to me than the mythological stuff that I explored at the Guthrie. It enabled me to find a wider variety of Louis’s poems than I had before.

It’s interesting you mention Jez Butterworth, because the play is reminiscent in a way of Jerusalem. There’s a similar feeling of one’s land being lost or of sacred property having finality to it.

You can’t help but feel that in the world at the moment. That’s the big question behind all of our lives—that we’re literally going to lose land as the waters rise because we’re not stopping our consumption. We’re literally going to lose our land.

When you approached Jenkins with the project, was he flattered by the idea? Did he want to be involved or sit back and observe what you did with it?

He was excited. He came to the workshop production and rehearsals at the Guthrie. He was very helpful with good ideas. He was always a bit concerned about the giants, but because he hadn’t worked on a play before, he let me have my way. This time I’m going to be truer to his words. But he’s been very enthusiastic about the whole process.

What I enjoy about Jenkins’s work is that he starts each poem with quotidian habits and everyday exchanges, then builds to moments of wisdom. It fits with the setup of these fishermen going, “Where’s your equipment?” and then building to larger moments of contemplation.

There’s a lot of sitting around when you’re ice fishing, so it’s a good place to think, and for someone to talk while the other person isn’t really listening and thinking about their own thing. That appealed to me. The thing with Louis’s writing is that it’s so dense and particular and funny and serious, and has an almost sonnet-like structure of developing a certain reality and then flipping, the way Shakespeare’s sonnets flip the last two lines. I’ve tried in the new version to have this kind of structure. I did love the Guthrie production, but it was encouraging to see how well the poems worked with only a minimal amount of writing from me.

There seem to be several moments that don’t directly correlate to what has just happened in the play. Is that what you’re exploring—that two people caught up with their thoughts don’t follow what the other is thinking?

Yeah, they might think about one aspect of what you’ve said and not the whole point of what you’ve said. And that came from a wonderful record by Howard Mohr called How to Speak Minnesotan; one of the funny sketches on it is about how Minnesota people speak in non-sequiturs.

There’s also affectionate mockery of regional culture, like how it makes no sense that ice hockey players wear shorts. I think even for East Coast audiences, you’ll have people who grew up in the Midwest or know Minnesota culture and will pick up on your wink about life there.

That’s a whole new aspect, how the East Coast will take it. I wonder if the East Coast audience will find it funnier, because in the Midwest it’s all normal. When Louis played a video of the 2008 workshop for his family in Duluth, they didn’t laugh at all, and at the end they said, “We had no idea your poems were funny.” Maybe I’ll someday take it to London; it’ll be such a foreign world for them.

There are certain moments that seem very challenging to execute onstage, like the scene where the wind blows Erik and Ron’s bodies horizontally. How do you stage those moments that depict natural elements?

Quite theatrically. There’s a lot of imagination demanded of the audience and flipping into double meanings. So the staging of Claire is very playful and not so naturalistic.

One of my favorite lines from the Guthrie version is when Ron and Erik are talking about seeing their breath in the freezing air. One of them says, “The cold here makes the invisible visible.” It’s such a beautiful line and seems to evoke the play’s larger ideas.

Oh, that’s one of my lines! But I think my writing is for another occasion. The play is really about working with Louis’s material. The idea of making the invisible visible is still true.

Lonnie Firestone is a frequent contributor to this magazine.