Circus has been a part of the American entertainment landscape almost since our nation’s founding (since 1793, to be exact). It’s an art form that’s both instantly recognizable and in constant flux, both kid-friendly and, as American Horror Story: Freak Show can attest, a harbinger of some of our deepest fears.

Ringling Brothers and Big Apple Circus both start touring the East Coast this January, keeping the vestiges of traditional circus alive. At the same time, artists all over the world are questioning and expanding the very definition of circus. As the Chicago Contemporary Circus Festival describes the form’s evolution: “The contemporary circus, already well established and respected in Europe, Canada and other parts of the world since the 1970s, is a mix of circus skill, theatre, dance, and music. It provokes emotion and feeling rather than focusing solely on technical skill.”

With Cirque du Soleil about to celebrate its 30th year in the U.S. and Les 7 Doigts de la Main performing in Diane Paulus’s Broadway revival and national tour of Pippin, opportunities to see “nouveau cirque”—a term used to denote circus based in fantasy and dance—are more available than ever.

But there’s more to new circus than nouveau cirque. Acrobuffos and Cirque Mechanics are two American companies combining old and new ideas about circus to create two very different types of performance. While their backgrounds and aesthetics differ, considering their work together provides an illuminating glimpse of how today’s circus work is developed, funded, and understood by other artists and audiences.

Acrobuffos is made up of a married couple, Seth Bloom and Christina Gelsone, who both come from the clown and street performance worlds. Their shows experiment with a variety of elements, including commedia dell’arte, water balloons, and contemporary visual arts. They’ve performed in almost 20 countries, and their newest show Air Play, a collaboration with air sculptor Daniel Wurtzel, will be showcased at the International Performing Arts for Youth conference at the end of January. As with a lot of interdisciplinary artists, their work resists labels and isn’t easily defined.

“Our priority and the one thing we cherish a lot is making people laugh,” says Gelsone. “As clowns, we don’t wear makeup, so some people don’t define us as clowns. We’re often told by different people that we’re different things.”

“A current across all of the shows we’ve made is that we don’t speak,” adds Bloom. “What I like about that is that it forces people to watch. And we can work anywhere in the world.”

Cirque Mechanics, led by director Chris Lashua, blends innovative large-scale machinery with acrobatics, highlighting the relationship between performer and apparatus. Their show Pedal Punk, which features a 22-foot pedal-driven metal arch and truss structure, just finished a fall tour of the U.S. Like Acrobuffos, they often have to educate presenters and other colleagues about what they do.

“Presenters would say, ‘That’s so cool, you’re not doing the same old cirque kind of thing,’ but they didn’t know how to market it,” Lashua explains. “We told them, ‘We want to play with the relationship between the rigging and the performer, we want to show off the magic that comes from revealing how it works, rather than hiding it behind a curtain of smoke.’ That’s what sets us apart from most of new circus.”

For both companies, collaboration is essential when developing a new piece. “We wanted to bring high art to populist theatre,” Bloom says of Air Play, “and we had no idea if it was going to work. Daniel Wurtzel met us—he’s worked Julie Taymor and Robert LePage—and he said, ‘Sure, take my stuff, experiment with it, let’s see what happens.'”

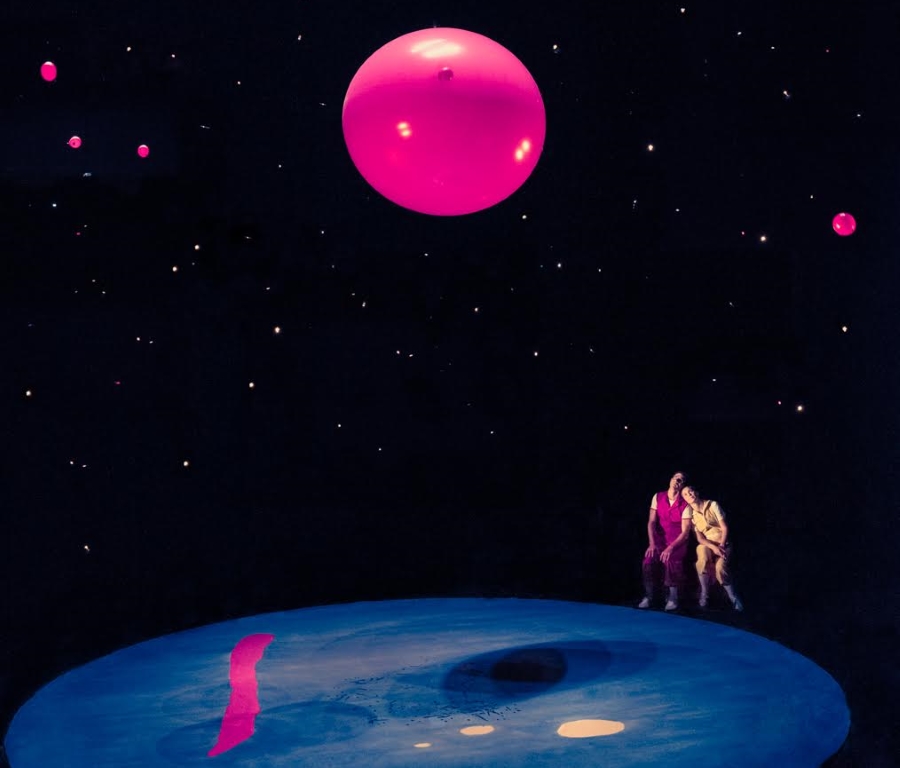

What followed was a methodical development period full of trial and error in a quest to get prop umbrellas, balloons, fabric, and other objects to move and float in just the right way. “We were in the studio and Daniel said, ‘I’ve got a mix of gases that can keep a balloon buoyant,’ and it took us a while to figure out the right ratio, but we made a three-foot balloon that stayed in the middle of the space. Christina went to lie underneath it and it looked like she was dreaming of a red balloon. That’s now a six-minute act in the show, just from that mucking about with Daniel.”

Lashua explains how Cirque Mechanics shows synthesize ideas from team members with a variety of different backgrounds. “My machine designer and I built this funky contraption on a previous show; he comes from an engineering background and wants to make the machine the star. I have to then put on my director cap and say, ‘That doesn’t allow us to tell the story we want to tell,’ and so we find compromise in that. Because these people have very different backgrounds, we get some contrast in terms of ideas, and I love that because I’m able to listen to all kinds of viewpoints and grab the things that I think are the strongest choices.”

Both companies also note that financial and logistical collaborations are just as important as artistic collaborations in creating their work, and it’s often difficult to separate one from the other. “European artists can get a fair amount of economic funding for a show, but we sunk a ton of our own money into Air Play,” Bloom says. The duo has paid for “everything except for space.” The size of their piece handily explains why: “The only way we could create a show of this scale is because of space donations,” Bloom says.

Playhouse Square in Cleveland, the New Victory Theater and Flushing Town Hall in New York, and Zoellner Arts Center in Bethlehem, Pa., all donated rehearsal space to the Acrobuffos and provided feedback throughout the process. “We were trying to make something we’d never seen before,” Bloom continues, “and all along this process, we’ve said to every presenter, ‘We want the right to fail.’ By saying that to ourselves, it let us not take the easy ideas; we had to push and find new ways of making a spectacle comic theatre, and every time we had a showing people said ‘keep going.'”

Lashua describes a similar process for securing the initial seed money to create Pedal Punk. “The gantry bike, which is a centerpiece of Pedal Punk, was really financed by a festival in Toronto,” he says. The festival wanted Cirque Mechanics to create something new, and could pay them a portion of what it would cost to create the structure. Lashua knew the company wouldn’t make their money back from the Toronto engagement, “but we knew we got to build this cool thing, the festival would be thrilled because they get to showcase something brand new, and then we get to have this thing afterwards, and we started to build a show around it. From that point, because this is our third production, we went to our agency, which already has theatres who are saying they love our work, and at that point it’s the agent’s job to sell them on the fact that we’re going deliver a show by a certain date.”

Acrobuffos’ and Cirque Mechanics’ work are appropriate for all ages, but they’ve had different experiences navigating exactly what that means. “In the U.S., we’re cornered very much into the children’s market, and when we’re in Europe, we’re considered good for everybody,” says Gelsone. “Often we perform exclusively for adults in Europe with the very same material that is labeled ‘children’s’ in the U.S. It’s very much a division inside the United States, and it’s kind of painful. It hurts to be pigeonholed.”

Cirque Mechanics has seemed to be able to avoid this kind of labeling for the most part. “The only place we play a children’s venue is in New York,” Lashua says. “We play in arts centers as a part of their general arts series, marketed to a general audience, not to a kid audience, but we do have to be careful about being pigeonholed as a kid’s show.”

Kiddie-show stigma aside, both companies agree that there’s a lot of innovation in the circus happening right now, and almost too many trends to keep up. “I think there’s much more interest in the U.S. than there was 10 or 15 years ago, and there’s more work being made,” Bloom says. “I also think there’s interest in it both for families and for adults, because people like to see spectacle. They like to see a different way of thinking about theatre and a different way of thinking about storytelling.”

Lashua emphasizes how self-sufficient artists must be as producers to get their work made. “There’s not a huge audience or presenter call for doing circus in a brand new way,” he says. “This is a push from the artists themselves.”

If the passion these two companies have for their work is any indication, we’ll continue to see more artists pushing boundaries in the circus world for many more years to come.

Emma Halpern is the co-artistic director of New York City Children’s Theater.