On a sunny Monday morning in October, seven Philadelphia actors gathered with Wilma Theater artistic director Blanka Zizka in the theatre’s studio space, a multipurpose room whose worn industrial carpet, stacked chairs, and dripping water cooler don’t seem particularly conducive to creative exploration, especially in the hours before noon. But make no mistake: Zizka is out to reinvent the Wilma.

Again.

The Philadelphia theatre, a hub of performing arts activity for more than 40 years—and Zizka’s artistic home for most of her adult life—is an old hand at the metamorphosis game, having survived an itinerant infancy and catch-as-catch-can adolescence to emerge as one of the city’s flagship cultural institutions.

But there are big changes afoot, beyond the expected brand refreshment that comes with artistic longevity or legacy planning. Zizka, 61, who has served as the theatre’s artistic head since 2010—when Jiri Zizka, her late husband and co-artistic director, stepped down from a leadership role—has been quietly forging a new path for the Wilma, interrogating every aspect of the theatre’s way of doing business, from project selection to casting to audience engagement, and taking radical steps to refashion them.

“We are in a time of transition,” she said in a recent interview, her occasionally idiosyncratic English delivered in a strong Czech accent. Soft-spoken and thoughtful, she comes off as serious, even studious, with an air of guarded confidentiality. “We have not completely given up on the old system, but we are in the groundwork of devising a new one,” she explained. If she succeeds, the once and future Wilma may well set a precedent for the nonprofit theatre of the 21st century.

The cornerstone of her vision is the newly christened Hothouse, an actor development initiative committed to rigorous vocal and physical training and equipped to function both as a workshop platform for upcoming productions and, she hopes, as a seedbed for the development of new work. Its nascent presence is evident—though perhaps not yet to outsiders, or even to the theatre’s subscriber base—in the current season, which is anchored by two Hothouse-assisted offerings: a striking and muscular Antigone, co-created with Theodoros Terzopoulos’s Attis Theatre of Greece, and The Hard Problem, a knotty new play about the knottier question of consciousness, by Wilma repertory favorite Tom Stoppard. (Two new American plays, Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’s An Octoroon and Lucas Hnath’s The Christians, round out the provocative season lineup.)

Antigone (seen in the fall) and The Hard Problem (which begins performances Jan. 6) seem to represent opposite aesthetic poles. The first, under Terzopoulos’s exacting direction, was an almost brutally athletic ensemble piece, performed in English and ancient Greek by a mixed cast of Attis and Wilma actors. The second (helmed by Zizka) is an intellectual exhibition match whose chief requirement, one would imagine, is linguistic virtuosity. What becomes clear, though, as Zizka details her worklist, is that the laboratory and training methodologies she’s putting into place—often in partnership with, or inspired by, theatre practitioners who share her holistic and collaborative ethos—can be cut to fit a variety of artistic undertakings.

“I want actors who are in their bodies, not in their faces,” she said. Watching her put that idea into practice is what brought me to the Wilma on that mid-October morning, as Zizka has expanded and formalized Hothouse activity this season by introducing weekly classes devoted to ongoing training and project exploration. Of the 12 or so core Hothouse company members (not all of whom could make it that day), most are Wilma regulars. They are paid a stipend and considered associate artists. In return, they are expected to attend 32 of the 42 six-hour sessions scheduled between September and June.

It’s a demanding regimen, and it was no surprise that it was already being tweaked: As a concession to the rigors of Antigone, then in previews, and because she herself was feeling under the weather, Zizka shifted gears for the day, asking the actors (after an “abbreviated” hour-long warmup) to read and talk and move though a new draft of her debut playwriting effort, a semi-autobiographical, dark comic vaudeville about a young Czech girl’s American dream. Its title, appropriately enough, is Adapt! This was Hothouse Lite, then, but an absorbing experiment nonetheless, like watching an episode of “This Is Your Life” as rewritten by Ionesco.

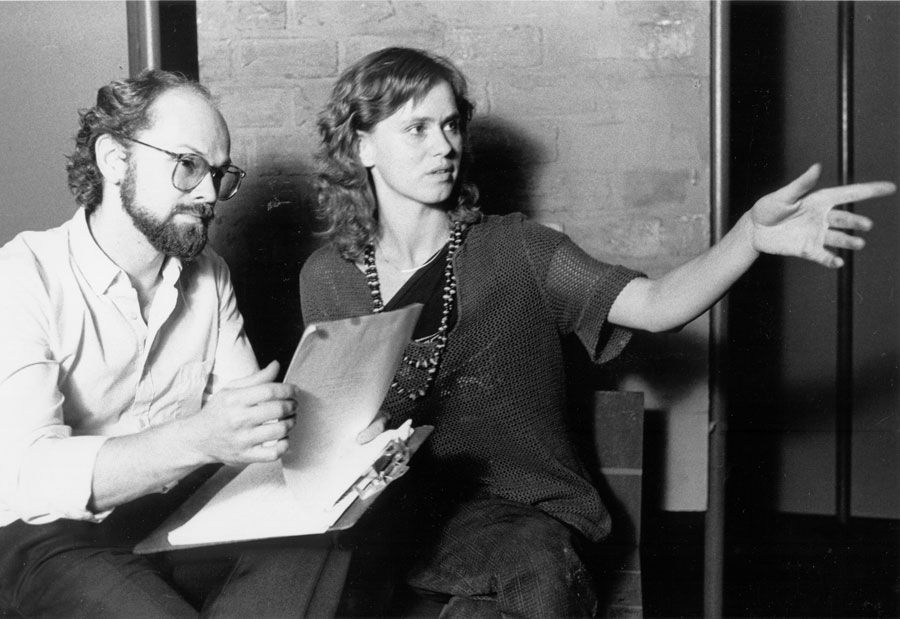

Zizka’s own American odyssey began in Philadelphia in 1979, shortly after she and Jiri, young artists who had recently defected from Czechoslovakia, landed at the Wilma Project (as it was then known), a feminist collective-cum-experimental arts showcase established in 1973. By 1981 the husband-and-wife team were made co-artistic directors of the fledgling company, which they transformed—with elbow grease, duct tape, and boundless energy—into the Wilma Theater, setting up shop in a former industrial space on Sansom Street and making themselves indispensable to adventurous audiences.

“It was a privilege to be able to do theatre,” said Zizka, recalling the shoestring productions of modern, mostly European dramas and adaptations (Orwell, Mrozek, Arrabal, Camus) that she and Jiri mounted—the kind of politically engaged, theatrically heightened work they loved but would never have been allowed to do in their Soviet-occupied homeland. “The idea that I could be paid for it didn’t even occur to me!”

At first, Jiri, with his sharp visual sense and conceptual bent, did most of the directing, with Blanka serving as co-director, actor, or choreographer. But as her skill set grew, they settled into a pattern of four-play seasons, usually dividing the directing assignments down the middle. Still, it was Jiri’s 1986 production of George Orwell’s 1984 that launched the Wilma into the national spotlight when it transferred, first to the Kennedy Center and then Off-Broadway to the Joyce Theater. The Zizkas, chomping at the constraints of their 99-seat space, began to set their sights on a brand new theatre.

It took a decade of fundraising and arm-twisting to get there, but in 1996 they took up residence in a gleaming 296-seat Hugh Hardy–designed theatre in the heart of the city’s new Avenue of the Arts redevelopment corridor on Broad Street. A high-profile inaugural performance of Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia, directed by Jiri, further solidified the Wilma’s ascendancy and signaled an expanded repertoire, one which would include a steady diet of the Czech-born Stoppard (the most produced playwright in the company’s history) and new plays by American writers like Doug Wright, Amy Freed, Dael Orlandersmith, Polly Pen, Charles Mee, Sarah Ruhl, and Robert O’Hara. The Wilma was no longer the little engine that could (newer companies like InterAct and Pig Iron were staking that claim), but a major player—along with the Philadelphia Theatre Company, the Arden, and the Walnut Street—in the city’s thriving theatre scene.

But this is not a story of hubris, of pride going before a fall. It’s not even a story of a fall. It’s the story of a changing theatre culture, of demographic shifts, of an economic slowdown, of artistic growing pains, and of heartbreak.

Walter Bilderback, who joined the Wilma as dramaturg and literary manager in 2004, sensed untapped potential in Zizka, even as her stock as a director was rising. (Her revelatory 2000 production of Stoppard’s The Invention of Love, hailed by critic Toby Zinman as “daring and gorgeous,” was an unprecedented critical and popular success.) “What was clear to me from very early on,” Bilderback said, “was that she was a rarity: a director who was capable of dealing with complex political and intellectual ideas, and the moment-to-moment questions both of acting and of an active design process.”

But over time, Zizka began to feel hemmed in by the Wilma’s hard-won but sometimes inflexible subscription season matrix, with its planning calendar imperatives and its bottom-line anxieties. As someone who had cut her teeth on the work of groundbreaking Polish theatre artists Jerzy Grotowski and Tadeusz Kantor, she found herself missing the urgency and community of Prague’s underground arts scene, where “just coming to the theatre was an act of courage.”

To be sure, building a theatre from the ground up was an act of courage, not to mention a labor of love, for the Zizkas, and Blanka is justifiably proud of their achievements. But she wonders now if the burgeoning nonprofit theatre movement of the 1970s and ’80s inculcated a certain cart-before-the-horse mentality.

“We were all interested in growth,” she acknowledged, “and artistic success seemed to be connected to the box office.” There was also pressure from boards and from funders, she said, to establish good business models, to invest in marketing and consultants, to hire new staff, and to expand operations. “I remember so many TCG conferences where—instead of talking about what project you were working on, how you experiment, how you are finding out more about your craft—we were talking about subscriptions.”

The tipping point for Zizka began about five years ago, when she became increasingly frustrated with the regional theatre’s cookie-cutter producing pattern: a vicious cycle of season planning, out-of-town casting, insufficient rehearsal time, and creative teams who rarely had the opportunity to meet face to face. “I started really thinking that in order for me to move my craft forward, we needed to work on continuity, and that became a mantra for me.”

At about the same time, continuity became a pressing internal concern at the Wilma. Jiri and Blanka had remained artistic partners long after their marriage ended (they divorced in 1995, before the Broad Street move), but there were inevitable strains, complicated by Jiri’s struggles with alcoholism. When Blanka was named sole artistic director in 2010, the very public transition in leadership—bluntly reinforced by Jiri’s death two years later—was a difficult, defining moment for the theatre.

Wilma staff members, including Blanka, seem reluctant to attach too much—or too little—significance to the fact of Jiri’s passing, but it obviously still carries weight and resonance. “It took us some time to recover and redefine who we are,” conceded James Haskins, Wilma’s managing director since 2006, “but I do feel that’s exactly what’s happened, and I think there came a point in time with Blanka where she discovered she needed to create her own independent artistic vision for this organization.”

Haskins has her back, even though many of her objectives are works in progress. “There’s a culture of regional theatre that I think is based in old models,” he said, “and Blanka and I both believe that if we allow ourselves to stay in these old models, we’re going to experience the same kind of slow and painful death that the newspaper industry has.” He sees his role as a facilitator, someone who can get the ball rolling, because Zizka is “the kind of director who, if there weren’t an opening night, would just keep rehearsing.” It’s important to start engaging, he said, and “to make adjustments based on the doing.” He and Zizka have been working doggedly to prepare for a January announcement of the Wilma’s “Transformation Fund,” a multi-million dollar campaign (already well on its way to completion) to support innovation in every facet of the theatre’s operations.

“I feel that, professionally, if I’m lucky, I have, like, 10 years,” said Zizka. “There is not a history of old women running theatres,” she added with a laugh. “Though [Ariane Mnouchkine of Théâtre du Soleil] is still at it. And Pina Bausch was still at it when she kicked the bucket.”

Zizka concedes that the shift in the theatre’s organizing principles—especially the idea of a company—could not have happened while she and Jiri jointly held the reins. “Jiri was not,” she ventured, choosing her words carefully, “a persons person,” but someone who preferred “to come up with work on his own, then kind of work the actors into it.”

She, on the other hand, has been moving steadily in a more collaborative direction, intent on making actors more fully “authors” of their own performances by expanding their interpretive range beyond the bounds of naturalism. For her 2011 production of Tadeusz Slobodzianek’s Our Class, which tracks the troubling fates of 10 Polish classmates, five Jewish, five Catholic, from 1925 to the present, she brought in Jean-René Toussaint, a French master voice teacher, to conduct a workshop with the cast six weeks before rehearsals started.

To call Toussaint a voice teacher is somewhat misleading, since his method, which he calls Primitive Voice, involves the entire body as a resonating instrument attuned to the expressive possibilities of memory, emotion, space, and time. He rarely works with text, preferring to improvise around themes, prompts, and emotional states, always with the goal of “allowing the unconscious life of a play to become visible.”

Zizka found the Toussaint workshop transformative, both in the tools it gave her to incorporate into her own aesthetic practice (an approach she’s calling the Thinking Body) and in the leg up it gave the Our Class cast as their collaboration continued. Since then, she has worked repeatedly with Toussaint, whose workshops and exercises have been foundational in the evolution of the Hothouse.

And in the evolution of Blanka. “Years ago,” said Toussaint in an e-mail, “I found her a bit unsure, but now I find in her an energy, a fire, that she takes from her surroundings. She is much more direct, and each hurdle becomes a challenge to welcome and to share openly. She is, in my eyes, younger.”

The Toussaint treatment—getting “the text into the body,” as Zizka put it—helped her crack The Hard Problem. The play’s dense surface—the outcroppings of Stoppard’s extensive research into the nature of consciousness, what philosophers call “the hard problem”—could easily be off-putting. Stoppard, she said, is more interested in his characters’ ideas than in their psychology, but “the fun for me is to get to those emotions that are underneath the ideas.” It’s not that she’s not invested in the mind vs. brain debate, which hones in on whether traits like goodness and altruism exist outside of biologically determined activity. It’s that for Zizka, the political is always deeply personal.

Stoppard, in an e-mail exchange, neatly sidestepped the question of directorial interpretation, except to say that the animating question of the play for him is, “What is the basis of moral value?” He can, he allowed, be a bit “hidebound” by his own notions in the case of early productions (the Wilma is among the first to bring the play to U.S. audiences), but he is content to let Zizka “go on her own journey,” trusting in her visual imagination, her intelligence, and their long association. “I think that I’m very lucky to have had the Wilma’s interest in my work almost from the beginning,” he wrote. “And there’s always a good creative atmosphere around Blanka. She’s quite tough as she needs to be in that job, but actors love working for her.”

That they do, according to Pat Adams, who ought to know—she’s now in her 20th season as the Wilma’s resident stage manager. Unflustered by the ups and downs she’s weathered, not to mention the undoubted drama behind the drama, she’s particularly enthusiastic about Zizka’s commitment to local actors.

“You can find everything you need right in your own backyard,” she said, but she also understands the underlying drive to foster excellence and depth of field in Philadelphia’s often-neglected acting pool. “If you want it to meet a certain standard, create the standard. That’s what Blanka’s doing,” she said. “There’s excitement, there’s trepidation, there’s fear, but she’s with them every step of the way.”

Playwright Paula Vogel knows a thing or two about excitement, trepidation, and fear, all of which she willingly took on in partnership with Zizka. Her Wilma-commissioned play Don Juan Comes Home From Iraq, produced in 2014, was a pilot project in Blanka’s quest to try out a kind of “slow food” new-play development model.

“How many of us who have been college administrators are thinking liability right now?” Vogel whispered to me during a 2013 “pre-script” workshop as she watched Toussaint lead Zizka and a group of actors through an intensely physical and often intimate series of exercises exploring the realities of bodies in battle, a given circumstance of Vogel’s then yet-to-be written play about a Marine’s homecoming, inspired by Ödön von Horváth’s 1936 expressionist drama Don Juan Returns From the War.

The play was cast from the workshop company while Vogel was still kicking around story ideas, giving her the opportunity to write in three dimensions, with and for a specific group of actors (something she’d never done before), and to open her process up to collaborators, including designers, at a much earlier stage than she was accustomed to. In other words, she was terrified. But working with Zizka, she said, made her realize that the playwright/director relationship, which she’d always considered a marriage, could be more like a call-and-response. The experience, she said, “has changed my DNA.”

Vogel has unwittingly returned the favor. As part of the Wilma’s outreach efforts during the development of Don Juan, she conducted several of her famous “boot camps”—crash courses intended to unleash each participant’s inner playwright—for various groups of veterans and active military. Everyone in the room—everyone—was invited to the party (somewhere in my hard drive there lurks an observer’s three-page Saddam Hussein opus). And Zizka, who needed no encouragement to channel a rogue’s gallery of scenery-chewing characters, was no exception. Though she didn’t realize it at the time, she had started writing a play.

There’s a scene in Adapt! when its young protagonist, Lenka, confronts an older version of herself, a vision of her possible future. The older Lenka puts on a 1960s recording of “These Boots are Made for Walking,” sung in Czech by Ivonna Prenosilova, and begs the girl to dance with her (“It’s one of my favorite songs!”). At that point in the Hothouse reading, Zizka pulled the song up on her laptop to play for the actors, and, just as you hoped, she started to sing along.

Janice Paran is a New Jersey–based dramaturg and writer.