The giant floating stone head that mediates between high culture and low has spoken—and it has cast its vote for science fiction. Walk in front of an audience filled with a collection of willing, educated theatregoers, and more of them are likely to have seen a recent episode of “The Walking Dead” than read The Iliad.

Sci-fi and fantasy have in recent years become regular features on the American stage, somewhat counterintuitively. Part of the reason for the influx is simply that we now have a broader understanding of sci-fi’s essence as speculative fiction than old-fashioned space operas. Today’s playwrights also understand that high concepts don’t necessarily require computer-generated special effects. There’s also a deep desire among contemporary writers to reach back and take hold of the work that formed them, and to look forward into an uncertain future.

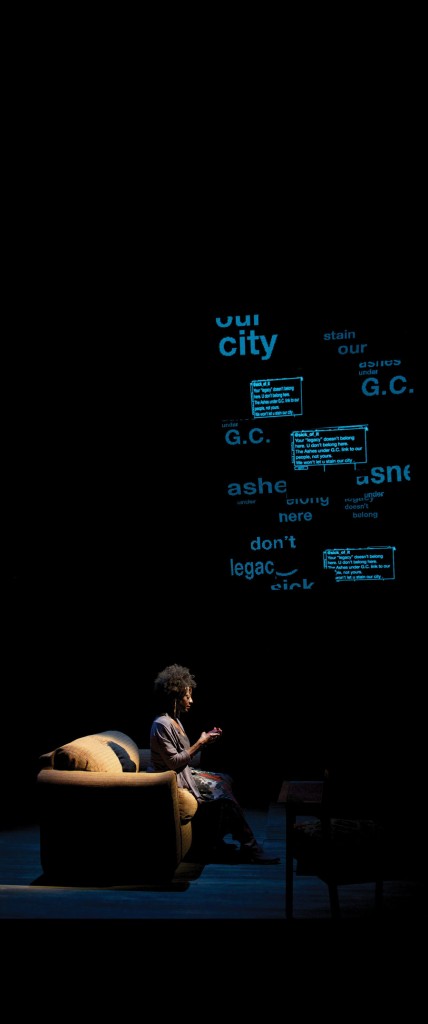

Three of those writers—Mac Rogers, Madeleine George, and Christina Anderson—talked with American Theatre about genre fiction and writing speculatively about the world(s). Rogers’s three-play cycle about an alien invasion, The Honeycomb Trilogy, ran in rep this past October and November at New York City’s Gym at Judson; George’s Pulitzer finalist, The (curious case of the) Watson Intelligence, which blends real-life science with the Sherlock Holmes stories in order to explore love and servitude, premiered at NYC’s Playwrights Horizons in 2013; and Anderson’s The Ashes Under Gait City, which imagines a charismatic leader trying to organize a black utopia via social media, appeared in 2014 at the Contemporary American Theatre Festival in West Virginia.

SAM THIELMAN: Everyone’s influenced by sci-fi now because it’s so pervasive culturally. Do you consider your own work to be science fiction?

CHRISTINA ANDERSON: I’d never thought of my work that way; I feel more comfortable with the idea of speculative fiction.

MAC ROGERS: I’m probably the exact opposite. The Honeycomb Trilogy is about giant insects taking over the Earth. They’re not campy plays, but they are science fiction, totally drawn from a number of pulp traditions. There’s no other term for it. The traditions I’m writing from are [Robert A.] Heinlein, Orson Scott Card, the “Doctor Who” I grew up on—there’s no classy way to present what I do. I do very much like the speculative side of things, as well.

MADELEINE GEORGE: I write a lot of fiction that has science in it. I have a play that has a robot in it as a character, but it’s not even a speculative play. The things in the play are happening right now. The robots exist. You can buy ’em. It’s a little bit more like: What would be the consequences of those choices? In that respect, I guess it’s speculative.

Science-in-the-fiction is really interesting.

GEORGE: I recently saw the really interesting and beautiful musical Futurity that’s being produced by Soho Rep and Ars Nova, and it’s an imagined interaction between Ada Lovelace and a Civil War soldier who want to work together to create artificial intelligence. Is that speculative? Is it imagined history? It feels like it’s speculative and historical simultaneously and that’s what I’m really interested in.

Mac was talking about grounding wild ideas in human emotions, but The (curious case of the) Watson Intelligence takes multiple timeframes and talks about ideas that transcend individual people and emotions.

GEORGE: When that play was first produced and people were asking me questions about it, they asked, “What do you see in the future of technology?” And I was like, “I dunno.” I’m mostly interested in what our technologies show us about ourselves as human beings. What do they show us about our internal human qualities? It’s not really a forward-thinking or futuristic question. It’s a classical or humanist question.

ANDERSON: When I got the [invitation to the roundtable], I immediately started looking into black speculative fiction and the African diaspora, and I think the conversations that I am interested in having with my work live in that black speculative fiction. A lot of my black sci-fi was Octavia Butler, you know; I’ve read her Parable series. I just picked up one of [Samuel R. Delany’s] books when I was in Chicago. I think the expectation with black artists is for us to teach or explain or to shine a light on historical events; I don’t think we’re often turned to have the “what’s possible” conversation in art. So with Ashes, I knew that there were already so many texts and plays and conversations around gentrification, and I knew that in the ’70s there was a push—and also even before then, in the ’60s and the ’50s—for these black utopias. So I was like, “Well, what if in the 21st century, you had black people who wanted to create a utopia? What if it wasn’t as much about them fighting to stay where they were as it was them saying, ‘You know what? You can have this. We’re gonna go find this other place that used to be ours and take it back.’”

There’s a huge diversity of political opinion in sci-fi. Mac, you just mentioned Heinlein and Orson Scott Card, a libertarian icon and a hardcore conservative, respectively, which is much different from, say, Delany or Butler’s perspective.

ROGERS: I have this problematic history with Orson Scott Card, because Ender’s Game is just a terrific general science-fiction novel—and he lived in Greensboro, N.C., and I grew up in Greensboro. So I have a special focus on Card. The whole thing with Ender’s Game is that humanity is sort of locked in an endless war against an insectoid species, a hive mind, and there’s absolutely no doubt that if you watch The Honeycomb Trilogy, the guy who wrote it read Ender’s Game; there’s some Orson Scott Card DNA. On one level, the third play is an expression of my kind of dissatisfaction with Ender’s Game, which climaxes with an extraordinary moment of mass murder carried out by someone who doesn’t know they’re doing that. That was disturbing to me even when I was a kid. I like to write plays where fully informed characters make really difficult choices, and there’s absolutely no way they can say they didn’t know the repercussions of those choices. I started getting a lot better at writing plays when I married the human drama that I liked writing with those sorts of pulpy storylines. Before that, I was writing these really turgid, extremely personal plays that nobody enjoyed. They were too long, there was always a dude who was obviously me in the play, and he was grumpy because girls didn’t like him.

I spent several years reviewing shows Off-Broadway, so I have some idea what you’re talking about.

ROGERS: A lot of times it’s because some guy’s trying to get revenge or something! They’re unbearable. I’ve written a bunch of them. But I discovered when I started writing these pulpy stories, I was liking writing the plays better, and because I was liking writing them better, the audience was liking watching them better. The joy I took in writing was very communicable. The emotions in our head, all the stuff we’re fascinated about in our own lives, is only a little bit interesting to the audience. You can’t write without it, but you have to remember the kind of stuff that’s only interesting to you. When I was younger, I was very bad at that.

Madeleine, you obviously put a ton of background work into Watson Intelligence. How do you balance the love story with the history?

GEORGE: The game of the play is the magic of several Watsons, including the guy who helped Alexander Graham Bell build the telephone, and Sherlock Holmes’s assistant, and the supercomputer that IBM developed, all played by one actor who plays another, fictional character. But it’s really about what it’s like to be in love with someone else! You can’t say in your press, “Come for Sherlock Holmes; stay for the crushing disappointment.” The play isn’t strictly about robots at all—it’s about what the impulses are that drive you to create, in this case, companion and social robots, to solve our problem as human beings, which is that other people are terrifying and disappointing. But you can’t really solve that problem without breaking into other and more serious problems.

What came first: notions about crushing disappointment or about robots?

GEORGE: I was really interested in the figure of the helper or the assistant. Like Watson—as in, “Come here, I want you!”—the famous Watson who was demoralized in that sentence, which was the first sentence conveyed by wire, and Holmes’s Watson. They’re an iconic type: the perfect assistant. I thought, “That’s interesting. I should write a play about that.” And then a year later, when the massively parallel natural-language processing computer went on TV, I thought, “That’s enough of a confluence to make something out of.” So it came out of the impulse of wanting to talk about what it’s like to be subordinate to someone else over the rest of your life. What is it to be forced into subordination, and what is it to make yourself available to that?

Does technology abet our desires, with respect to that?

GEORGE: The thing that’s so interesting about social robots and natural language processing computing is that we feel like technology helps us solve our problems. We can’t get someplace fast enough, so we make an airplane. We can’t get inside of someone’s body, so we develop a laser. Tools are always good for us, right? Except, can we really improve on the intractably painful and difficult interactions between ourselves and everyone else around us? It’s possible that the relationship between us and a tool that’s of our own creation, while it feels safer, isolates us in a way that is so profound, and the difficulty of attachment and loss is the meaning of other people. You can’t extract it and improve the situation. We become less and less capable of being ourselves.

How do you mean?

GEORGE: Do you know Sherry Turkle?

I don’t.

GEORGE: She’s a psychoanalyst and philosopher at MIT. She’s embedded in the department with the roboticists, and for years she’d been writing about the effect of technology on relationships. Her contention is that we’re trying to insert more distance, to create more distance with the things that are closest to us. So people are always sitting together and communicating with people who are elsewhere and trying to communicate with people in ways that are much more controlled. She says a lot about the art of conversation and how it’s basically the pinnacle of human achievement.

Christina, how do you set up those alternatives you mentioned earlier—the combinations of histories that make a world?

ANDERSON: I learned a lot with Ashes Under Gait City; I made up a lot of the history, but it was influenced by actual events. I’d wondered about the history of penal colonies, and then I read about Australia and thought, “What if they put one on Liberia?” and that’s my play pen/man/ship. It’s set in 1896, when Jim Crow was made constitutional, and this black land-surveyor has been given permission to go start a penal colony in Liberia. When the shipmates mutiny, his female companion becomes their leader. I read O’Neill’s ship plays, and I thought men were treated like such animals, which I’m sure was true, but I asked myself, “What would happen if men who’d been on a ship for years chose a woman to be their leader? And then what kind of woman could command them?” And then people kept asking me, ‘Wouldn’t she have gotten raped?” I always have these awkward conversions with people: “She needs to get raped!” “How come nobody’s slapped her?” It’s interesting. With these plays, a lot of conversations come up around historical accuracy. I’m not denying any of that, but I don’t think I’m living in revisionist territory. I don’t think there was ever any attempt to start a penal colony in Liberia, but I took a lot of the history of Australia and made it about black people. It was about building a world.

I think that’s the way a lot of great genre fiction gets built. I like the George R. R. Martin novels a lot, but so much of it is just the War of the Roses.

ANDERSON: Also, read Shakespeare! He just plays this huge game of “what if.” I have the freedom to take these things and put them together like a Lego set of sorts.

GEORGE: With both of you, with the speculative and the pure genre, I feel like, “Why theatre?”

That’s a great question.

GEORGE: Plays are so about what the limits of a human being are. You don’t have special effects in the theatre; you have theatre magic. Why write genre?

ROGERS: I’ve written five or six science fiction plays over the last 10 years, and I’m taking the forms that have worked over and over again in theatre: Advance Man, the first play in a trilogy, is very much a “living-room play,” and it has a latter-day Albee weirdness to it, as well. The second play, Blast Radius, is in the Shakespearean pastoral tradition, where scenes kind of alternate between nobles and commoners; there are some people in disguise, and it ends in lots of weddings, but in a very messed-up way. The third play, Sovereign, is very much in the tradition of the real-time Greek tragedy about a great ruler who is in the process of falling. There’s hubris; there’s a dispute over a burial. I just said, “These things work! These things have been honed!” Maybe someday I’ll have my own theatrical traditions, but I’m trying to fit them into forms that I know work in the theatre.

GEORGE: And you’re going back in time. That’s so cool.

ROGERS: You guys may have other answers, but basically I wanted to.

ANDERSON: I wanted to, too.

GEORGE: Me, too.

Sam Thielman writes about technology and business and, when he can get away with it, culture for the Guardian. He lives in Brooklyn, obviously.