Theatre Facts 2014 Overview Based on the TCG Fiscal Survey, Theatre Facts 2014 examines financial, performance, and attendance data supplied by TCG Member Theatres for fiscal years concluding anytime between Oct. 31, 2013, and Sept. 30, 2014. The report was written by Zannie Giraud Voss and Glenn B. Voss of Southern Methodist University, with Ilana B. Rose and Laurie Baskin of TCG. Theatre Facts 2014, replete with detailed charts and graphs, can be found here, along with earlier Theatre Facts editions. The report presents three perspectives: The Universe section offers a broad overview of the U.S. professional not-for-profit theatre field in 2014, which included an estimated 1,770 organizations. The Trend Theatres section explores changes over time, with longitudinal analysis of the 118 TCG Theatres that participated in the Fiscal Survey yearly since 2010; there’s also data for 88 theatres that participated yearly since 2005. In this article, all references to Trend Theatres denote the five-year analysis, and all figures are adjusted for inflation. The Profiled Theatres section provides a detailed examination of all 177 TCG Fiscal Survey 2014 participants and breaks those theatres into six budget groups, based on annual expenses—from Group 1 (annual expenses of $499,999 or less) to Group 6 (expenses of $10 million or more).

As the Great Recession finally fades into memory, theatre leaders seem relieved to have other issues on their mind. The glass is looking more than half full these days, with a rise in funding from foundations and individuals driving an overall increase in income, and more than half of theatres experiencing a positive bottom line. Even so, rising costs and ongoing challenges in retaining and building audiences and managing cash flow are keeping managing and artistic directors wary.

That’s the thrust of the data in Theatre Facts 2014, the annual report on the state of the U.S. professional not-for-profit theatre from Theatre Communications Group, and the general consensus in a dozen interviews with the people running theatres, large and small, from around the country.

Paul R. Tetreault, director of Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., says outsiders sometimes forget that not-for-profits “already were being run without a lot of fat, so the recession really hurt when we had to tighten up on spending.” Tetreault says that everyone is still “running tight to the bone” these days, but that perceptions have changed in recent years: “I think people feel a lot less uncomfortable than we did when the guillotine was hanging closer to our necks.”

Ted Pappas, producing artistic director of Pittsburgh Public Theater, says he’s “actually rather optimistic about the future,” and adds that he thinks most people running theatres share that outlook “because you can’t go through this every year without believing you will survive.”

Theatres that were fiscally conservative were the ones best prepared to bounce back with the economy, says Jason Kralicek, managing director at the Unicorn Theatre in Kansas City, Mo., though he adds that the theatre companies also need to continue responding to changing circumstances. “We have to be able to be nimble,” he says.

Michelle Mulholland, managing director of Golden Thread Productions in San Francisco, agrees, saying that her company did more belt-tightening even as the economy started improving, but that future success will come from rethinking old habits. “We have to figure out how to innovate,” she says.

“We are trying to remain limber and respond to opportunities,” adds Dorothy Ryan, managing director of Theatre for a New Audience in New York City.

Theatre Facts shows that while the average Trend Theatre supported more of its expenses with earned income than contributed income each year, the latter saw greater growth over the five-year period, despite significant declines in all areas of government funding. Average federal funding fell 56 percent in inflation-adjusted dollars from 2010 to 2014, state support was 19 percent lower, and city/county support 27.8 percent lower in 2014 than in 2010.

“We’re in a deep-blue state but our state funding for the arts is in rough shape,” says Sarah Horton, managing director of Artists Repertory Theatre in Portland, Ore., who adds that the money awarded is “a small fraction of our $3-million budget and still requires a considerable amount of effort to secure.”

But it’s not just the government that’s become less reliable as a source of support: Average corporate giving grew only 0.5 percent in inflation-adjusted dollars over the five years and those dollars supported 0.3 percent less of expenses. After the recession, Horton says, corporations felt they couldn’t give money to “anything that looked frivolous.”

Theatres do find that they can still tap corporate and government dollars for educational programs. The percentage of corporate gifts earmarked for education programs rose from 13 percent (2010 through 2012) to 16 percent by 2014, and there were also slight increases in the percentages of federal and state funding earmarked for these programs. Earned income from education and outreach programs (classes, artists-in-schools programs, etc.) also climbed, with five-year growth of 14 percent above inflation; roughly one third of that income came from arts-in-education/youth services programs.

Janette Cosley, executive director of the Ensemble Theatre in Houston, says her theatre holds a golf tournament specifically to fund its youth programs, and that it proves “an easier draw for money than our gala.”

The programs themselves are also an easier sell. Says Paul Savas, artistic and executive director of the Warehouse Theatre in Greenville, S.C., “We can go into schools with NEA funding and we can go to companies and say, ‘We’re teaching the soft skills you say you need, like analytics, communication, and how to work in teams.’”

“I used to talk about plays in my speeches, but now I always talk about plays and education,” Pittsburgh Public Theater’s Pappas says. “It draws people in who are not drawn in by the theatre.” And this isn’t just a sales pitch, he points out. “Our education program brings together kids from different parts of the city and builds an audience of new theatregoers, so while the message is irresistible, it is not a stunt. It is legitimate.”

Fortunately, as government sources and corporations take a smaller role in theatres’ funding, foundations and individuals are picking up much of the slack. Average foundation support was 38.6 percent higher (adjusted for inflation) in 2014 than in 2010, and covered nearly 2 percent more of expenses. Nearly 60 percent of all theatres had foundation support grow faster than inflation over five years. Individuals—trustees and non-trustees alike—stepped up, too, with their giving outpacing inflation by 25.4 percent while supporting 2.4 percent more of expenses. Average trustee giving led the way, growing by 33.5 percent above inflation. The combination of foundations, individuals, and fundraising events covered 33.4 percent of expenses in 2014, up from 28.4 percent in 2010.

Writing grants for foundation money and wooing individuals is far more time-consuming than getting one big corporate check, Pappas concedes, but the shift in resources is necessary (he also says he believes that corporate donations may eventually cycle back).

“Like Willie Sutton said, ‘You have to go where the money is,’” adds Michael Maso, managing director of Huntington Theatre Company in Boston. “We’re investing most of our effort in getting individual donations.”

“We never had a strong formal campaign for individual giving but now we do,” Ensemble Theatre’s Cosley says, adding that as a leader of an African-American theatre, she can rally a specific community for support. “It has helped our bottom line enough to create a rainy-day fund.”

Even Golden Thread’s Mulholland, whose board members have been getting the corporations where they work to kick in, says she is shifting her focus to individuals. “We’re redesigning our approach, so instead of generic spring and fall campaigns we are doing it once a year and targeting what the individual is interested in,” she says.

Unicorn Theatre’s Kralicek says his theatre has not yet seen growth in that area, but counts the Theatre Facts report itself as an eye-opener. “We definitely see individual giving as an area we need to put more resources into,” he says. “There’s an opportunity there. When you look at the trends and see the other theatres you say, ‘If they can do it, we can too.’”

Demographics can present challenges, however. Mark Booher, artistic director of the PCPA–Pacific Conservatory Theatre in Santa Maria, Calif., points out that 65 percent of his town is working-class Latino, while a few miles away is a town filled with millionaire retirees. “But we don’t want to start pandering to them, so we have more work ahead,” he says. Additionally, while PCPA receives $2 million annually—more than half its operating budget—from its conservatory relationship with Allan Hancock College, that creates a perception problem among potential donors, who feel they don’t need to give. “We end up weak on contributed income and very box office–dependent,” he says.

At the Roadside Theater in Norton, Va., managing director Donna Porterfield says that most of the audience is poor and working-class, which limits individual donations, and many foundations are focused on basics like getting food and education for the locals. Yet with the coal economy crashing, the theatre suddenly holds a new appeal. Roadside is part of Appalshop, a multidisciplinary arts organization that focuses on the region’s history and culture, but now foundations and even local politicians in Virginia and Kentucky are seeing Roadside and Appalshop as more than “a way to break stereotypes and poor self-image,” says Porterfield. “They see us as an economic development opportunity—we are giving young people training and giving them a way to stay in the area and work.”

Beyond the contributed-income story, the good news can be seen in a series of Trend Theatres’ snapshots: Total ticket income was up 4.2 percent over the previous year, with the number of resident performances continuing to rise. Average payroll rose over the past five years for artists, administrators, and production/technical staff (total compensation growth of 12.1 percent above inflation), while expenditures continued to decline in inflation-adjusted dollars for physical production materials and other technical production, non-personnel expenses. In other words, theatres are healthy enough to either pay their staff better or expand their payrolls.

There’s more good news in theatres’ Change in Unrestricted Net Assets (CUNA), which equals the total unrestricted income minus total expenses and “represents the annual bottom line, indicating whether or not the organization brought in enough income to cover its expenses,” in the language of Theatre Facts. According to the report, the average Trend Theatre ended 2014 with a positive CUNA equivalent to 2.9 percent of total expenses. Half or more of theatres had breakeven or positive CUNA annually, with 2010 showing the greatest proportion of theatres operating in the black and 2012 the lowest. While 8 of the 118 Trend Theatres finished each of the five years with a negative bottom line, 14 Trend Theatres (nearly 12 percent) were at the opposite end of the spectrum, ending every one of those years in the black.

“It’s important to us that we end each season in the black,” says Pittsburgh Public Theater’s Pappas. “We do constant assessments of our situation, starting the first day of the season to see what has changed in anything from lumber or fabric costs to subscription numbers.” Pappas says every department attends monthly meetings to provide assessments and make adjustments. “If there is a $50,000 issue, we are not going to find a $50,000 solution. We are going to find 50 $1,000 solutions, and every department has to come up with savings or additional income.”

Pappas acknowledges that this vigilance is “exhausting” but proudly says he has never had to send an SOS letter to donors. “Too many theatres are used to crisis management mode. They get into trouble because months go by and in March they suddenly realize they are $300,000 short to balance the budget,” he says. By contrast, careful planning means never having to make commercially safe programming choices to please an anxious board. “It allows me the creative freedom to produce what we want.”

But PCPA’s Booher points out that for a struggling theatre, finishing every year in the black can be costly. “We had to lay off two staff members and cut a show out of the season one year. It was the only way to be responsible.”

And many of the positive statistics in the report have a less-rosy flip side. The growth in payroll means more theatre people are earning a better living, but it also means that expenses are on the rise; the five-year trend shows growth rates (adjusted for inflation) of 7.3 percent for earned income and 12.6 percent for contributed income but 9.1 percent for expenses. Rising healthcare and minimum-wage costs have some leaders worried about more painful numbers on the expenses side of the ledger.

Booher explains that as minimum wages rise, other salaries must also be raised accordingly, which has “a really significant impact.” For his theatre, the possibility of payroll and insurance costs going up without income coming in to offset that might lead to layoffs.

While total net asset growth was healthy, exceeding inflation by 15.2 percent, and capital campaigns (for facilities, endowments, artistic reserves, etc.) have led to higher numbers in long-term investments and fixed assets, working capital—the unrestricted resources available to a theatre to meet day-to-day cash needs and obligations—remained negative in each of the last five years (though it improved slightly in 2013 and 2014).

Annually, 68 to 72 Trend Theatres showed negative working capital, and more than half had negative working capital in each of the past five years. Sixty-one percent of those improved their situation between 2010 and 2014 while remaining stuck with negative working capital, and 14 percent made the leap from negative to positive in that span. This is important, the report’s authors explain, because “working capital is a better indicator of a theatre’s operating position than CUNA, which includes non-operating activity and doesn’t reflect the theatre’s savings or outstanding obligations.” Negative working capital is cause for serious concern since it “indicates that a theatre is borrowing funds (e.g., dipping into deferred subscription revenue, delaying payables, taking out loans, tapping lines of credit, etc.) to meet daily operating needs.”

Cash flow is often a major issue regardless of an institution’s size, Mulholland says, adding that when expected funding for Golden Thread’s ReOrient Festival fell through in 2012, they were forced to launch an emergency campaign. While the Kickstarter campaign raised a little over $14,000 and was their most successful such campaign, she still had to reduce the scope of the festival. At other times she has sought bridge loans or cut back on the number of full productions.

“We are constantly having to make stupid choices on expenses because cash flow won’t allow us to make smarter ones,” says Artists Rep’s Horton, pointing to things like paying high rental fees for equipment that they can’t buy because they lack the cash or credit, even though that would save money in the long run. “Equally damaging is the fact that I spend a huge percent of my time managing cash flow at the expense of staff management, donor relations, and strategic work.”

A related statistic, working capital ratio (the proportion of unrestricted resources available for operating expenses), illuminates how long a theatre could meet short-term obligations on just its current resources. The persistent negative ratios mean theatres are regularly battling through cash-flow crunches, though 2014 ended 18.5 percent better than 2010. According to Cool Spring’s Analytics, cited in the report, 25 percent or 3 months of funds can be considered a reasonable benchmark for adequate working capital to handle most cash-flow fluctuations. In 2014, only 9 percent of Trend Theatres hit this mark.

Cash flow, Horton says, “has been our No. 1 issue and obstacle to operating the theatre strategically for at least the last five years.” Artists Rep took possession of its building 10 years ago but was undercapitalized at the time and has since required “various acts of heroism,” from individual donations to special fundraising campaigns, and has been forced to pay bills slowly or cut staff. Horton hopes to find ways to leverage their equity in the building but in the meantime, says, “We’ve come up to the edge of the cliff more times than I care to recall in the last five years. And while we’ve been keeping the cash-flow wolves at bay, our ability to do that isn’t unlimited.”

Even theatres in stronger financial shape must constantly reassess. “Everything always takes longer than you think and costs more than you think,” TFANA’s Ryan says, which is doubly true in New York. TFANA made “best assumptions built on solid logic” when budgeting for its move from Manhattan to Brooklyn, but everything is always shifting. “We thought we’d need a security guard in the lobby at all times but we didn’t, yet we had to hire more ushers,” Ryan says. “And we extended three of our four shows, which generates more revenue but which is also more expensive.”

In 2014, 53 percent of Trend Theatres had positive CUNA, up from 2013 and 2012, but still lower than 2011 and 2010. On an optimistic note, 2014 saw the smallest slice of Trend Theatres with negative CUNA exceeding 20 percent of their budget, and the majority of theatres had CUNA between 10 percent above and 10 percent below breakeven in each of the five years. For those theatres in the vast middle, though, the news was not all good: The percentage of theatres with a CUNA between negative 10 percent of the budget and breakeven has grown steadily, while the theatres finishing with CUNA between breakeven and positive 10 percent of the budget have declined. In other words, more Trend Theatres are finishing a little in the red instead of a little in the black, leaving them more vulnerable if an internal or external crisis arrives.

“The real solution is to increase our contributed and earned revenue to a level that will provide us with enough cash on hand to manage the day-to-day expenses,” Mulholland says, adding that Golden Thread has just begun a strategic effort on that front by hiring a full-time marketing director, overhauling their individual donations strategy, and working to develop their board of directors, and they have received foundation assistance and a loan to help get them down this road.

Some theatres are fortunate to have a structure that reduces those stresses. Stephen J. Albert, executive director of Court Theatre in Chicago, says that being housed at the University of Chicago means not paying rent or repair fees. “It’s one of the great models and has given us extraordinary freedom,” he says.

The Roadside Theater in Norton, Va., is much smaller, and Appalshop lacks the resources of a prestigious big city university. Yet Porterfield says that relationship still is vital in helping Roadside avoid cash-flow concerns. While Roadside brings in most funding before the fiscal year starts and cuts the budget if a grant doesn’t come in, there are always unusual circumstances. For instance, she says, NEA funds are paid on a reimbursement basis so Appalshop can lay out the money for Roadside until the NEA payment arrives.

Tetreault points out that Ford’s is “an anomaly” because it is as much a historic site and education center as it is a theatre and can sell all that to potential donors. “We get the biggest corporate support of any arts group in Washington outside of the Kennedy Center,” he says. “And it’s not because they love the theatre—it’s because they love President Lincoln and our relationship to people on Capitol Hill.”

Indeed, as strange as it sounds, the 150th anniversary of Lincoln’s assassination brought Ford’s an additional $2 million in corporate funding. “This protects us if shows falter at the box office,” he says.

Ticket sales and attendance are other areas of continued concern. While ticket income is up, that is in part thanks to higher average prices. But total ticket income covered 39.6 percent of expenses in 2014, on average, compared to 42.9 percent in 2010. And the number of tickets sold continues to decline, with 2014 producing a five-year low in both single and subscription tickets sold (though not the number of subscribers), which is worrisome. “Is there still going to be an audience?” Pittsburgh Public Theater’s Pappas asks. “We need to build an audience of the future.”

Attendance for resident productions and tours fell to a five-year low in 2014, even though more than half the Trend Theatres saw total attendance rise over time. Removing tours from the equation, there was a 3.7-percent climb in the number of resident performances, yet a 1.9-percent drop in attendance at those productions, and 52 percent of the Trend Theatres saw a decrease in resident-production attendance.

The main series performance and attendance numbers followed suit, as about half of theatres reduced the number of main series performances while half increased the number. Just under a third of the theatres that cut back on performances found it led to attendance growth, and just over half of those who increased the number of performances found it yielded at best lackluster growth or at worst a decline in attendance.

Booher, who at one point had to cut down PCPA’s season by one production (though he has since restored his programming), points out the danger that a box office bust “does more damage and can leave you with an even bigger revenue problem.”

There is one bright side, says Warehouse Theatre’s Savas, who moved from seven mainstage productions down to six productions four years ago and is now down to five. Fewer productions with longer runs means “turning weeks of rehearsals, which are all expenses, into weeks of performances which generate revenue, and that’s a no-brainer,” he says.

The one purely happy story was children’s series (defined as production series for young audiences by theatres that are not Theatre for Young Audience theatres). There was nearly 10-percent growth in the number of children’s series performances over the five years and attendance reached a five-year high in 2014, climbing by 12.9 percent over that span.

Subscriptions, long a staple of not-for-profit theatres, are now a bit of a conundrum. While subscriptions remain the second largest source of earned income, average subscription income dipped slightly (0.8 percent) in 2014 after four years of tepid growth that left it 2 percent lower in 2014 than it was in 2010 if the figures are adjusted for inflation. The five-year increase in subscription ticket prices was 1.6 percent above inflation, which was not enough to offset the decline of 2 percent in subscription tickets sold from 2010 to 2014. As a result, subscription income covered less of a theatre’s total expenses, on average, down to 15.3 percent in 2014 from 17 percent in 2010.

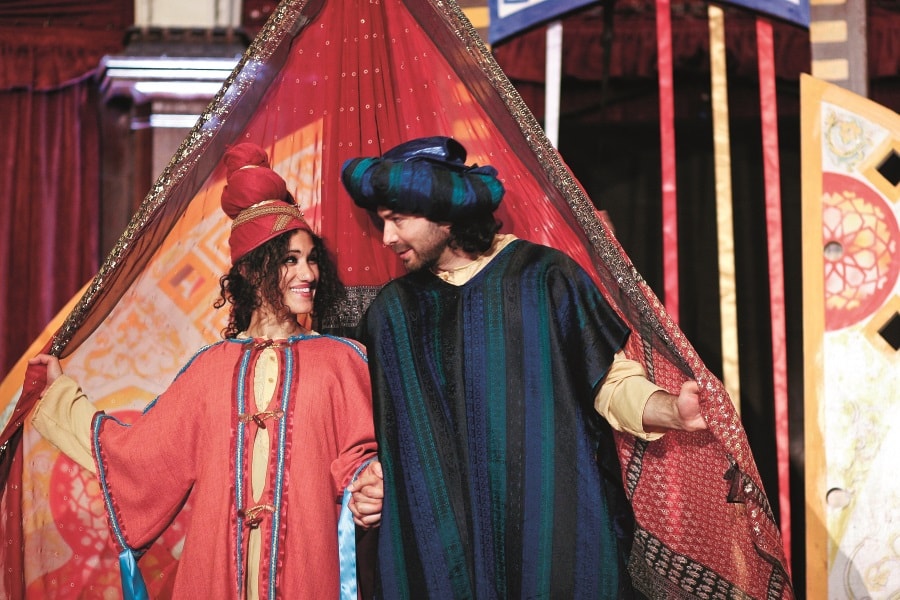

It’s also important to note that unusual circumstances can alter a theatre’s performance in a given year. Ryan points out that when TFANA left its itinerant Manhattan existence behind for a spectacular permanent home in red-hot Brooklyn—and then opened the theatre with Julie Taymor’s dazzling and headline-grabbing production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream—TFANA doubled its audience and tripled its subscriber base because people were willing to subscribe just to get into Midsummer.

Still, for many theatres, creativity has helped staunch the bleeding. Flexible subscription income accounted for 12 percent of total subscription income in 2014, the highest percentage of the five-year period—a sign that theatres are finding a way to keep audiences, even if it requires more work and provides a bit less certainty. Nearly three quarters of the 123 Profiled Theatres that offered traditional subscriptions also offered flexible subscriptions and/or memberships. Another 27 theatres chose to forgo the traditional subscription entirely for flexible subscriptions and/or memberships. “We have a lot of smaller packages and offer a lot of flexibility,” says Court Theatre’s Albert, adding that full subscriptions are “such a commitment” for the over booked modern individual so people prefer choosing two or three shows.

The Ensemble Theatre has added a lower-cost package targeting young professionals, says executive director Cosley, who adds that flexibility for subscribers in changing around their reservations makes the staff “all go crazy” but is necessary to keep customers returning; Ensemble had only 500 subscribers in 2003 but quadrupled that total by 2006 and is slowly trying to inch up to 3,000.

“Our season subscription numbers are a little low, but we are increasing the number of butts in the seats,” the Warehouse’s Savas says. The company’s space is a black box with general admission so ticket plans can naturally be more flexible. He says they do a limited number of discounts—for students, but also active military and veterans, which is hugely important in South Carolina—and do not provide senior tickets. “That would be half our audience and we’d lose too much revenue,” he says.

Savas says his theatre continues seeking new ways, perhaps punch cards, to “challenge the season ticket model and change purchasing habits, but it is hard to find answers.” Last year his theatre hired their first full-time marketing director. “With six full-time people we are putting a lot of capital into increasing our numbers,” Savas says, and the marketing is paying off with single-ticket sales, which are on the rise.

Single-ticket income remains the single greatest source of earned income annually, although it lacks the stability provided by subscription packages. Average single-ticket income for Trend Theatres increased between 2010 and 2014, with growth exceeding inflation by 1.6 percent, although as with subscription tickets it now supports a lower percentage of average total expenses (a dip of 1.7 percent). Single tickets sold essentially held steady with a drop of just 0.3 percent from 2010 to 2014, even as the average price climbed 2.7 percent above inflation. Most of that growth was in high-end tickets—the lowest single-ticket price lagged inflation by 5 percent while the highest single-ticket price surpassed inflation by 27 percent.

“It’s part of the shift in buying patterns and how audiences see theatres,” Huntington’s Maso says. “Our single-ticket sales are substantially higher than 10 years ago and the growth is steady. So we are spending more money on single-ticket marketing.”

Maso adds that finding that “magic mix of how to spend marketing money is a constant struggle,” not just between ticket plans but between digital and traditional outlets. He adds that Boston is an unusual market because “people still read print,” so they hired someone to help market in both arenas.

Of course, as with every trend in this report, there are theatres that are experiencing the exact opposite of the pattern. For instance, Albert says Court Theatre has a stable subscriber base with an 80-percent renewal rate, in part because Chicago is such a strong theatre town and in part because of its home at the University of Chicago, where “people see intellectual engagement as entertainment.”

Horton says that Artists Rep has “gotten traction with flex passes,” so subscription retention has grown since 2010 even as they’ve raised prices. “This year we’re embracing the fact that this is where our growth is and pushing more there and less on single tickets,” she says.

Beyond ticket sales, theatres are finding numerous other ways to boost their earned income and are finding mixed results across categories. Five-year growth in production income (from coproductions and commercial producers) surpassed inflation by 73.9 percent; theatres added 12.2 percent more tour performances over that period with an 11.2-percent growth in attendance; booked-in event income (shows, films, or events presented but not created by the theatre) grew by 33.4 percent over inflation, with 34.6 percent more people attending booked-in event performances in 2014 than in 2010; and rental income continues to increase, reaching a five-year high in 2014 and showing 101.3- percent growth over the five years after accounting for inflation. (Royalty income did fall, however, dropping four straight years, with an overall decline of 34.8 percent after adjusting for inflation.)

Booher has found new revenue in PCPA’s 14,000-square-foot prop and costume warehouse, renting out items he has already used to smaller theatres. Booher believes he can triple that starting this fall with a new website and rental coordinator staff position. Typically, though, rental income comes from the theatre’s stage and rehearsal spaces.

Maso says that the Huntington’s rental income, which includes weddings and corporate events, is “not insignificant,” but that the theatre loses some of that money when it subsidizes the costs for smaller theatres that perform in their theatre or even stage shows in their rehearsal halls.

But there are benefits beyond the obvious bottom line. “It’s a critical investment in the theatre scene,” Maso says, adding that foundations like seeing a theatre play that leadership role in a community. “Foundations love to hear that you own your building because you have a revenue stream, but also because you are helping the community,” Ensemble Theatre’s Cosley says.

Horton agrees, saying they have made their building into a “community arts hub” (including visual arts) with “significant civic value” and she can “leverage that to get funding.” She adds that her setup provides an additional benefit because their scene shop and technical services are used by the other theatres, which allows her to retain staff year-round with benefits instead of laying people off each spring and hoping to get them back come fall.

Most ways to supplement earned income make relatively minor additions to the bottom line but many of them also make contributions that are not so easily measured. That, of course, makes them vulnerable to cuts in tough times. Steady growth in concessions income produced a five-year high in 2014 that surpassed inflation by 43 percent, though it covered a mere 0.4-percent increase in expenses in 2014 than in 2010. “We really ramped up concessions and doubled that income from the mid-30s [in thousands of dollars] to the mid-70s,” says Artists Rep’s Horton.

“The biggest thing for us was that we finally got a liquor license,” Court Theatre’s Albert says. “We can really change the audience experience.”

Kralicek agrees, saying Unicorn Theatre used the financial crisis to leverage a new bill passed in Kansas City to make it easier for not-for-profit performing arts institutions to get liquor licenses in areas where they were limited. “It’s not a huge amount of revenue but now people can enjoy an evening out like they would at other entertainment options,” he says.

In Brooklyn, the potential is for more than just a drink or two. TFANA has a book kiosk and gourmet café currently open during performances. It does not generate much revenue, Ryan says, but adds value to customers who come straight from work. However, Ryan says, with a 52-story tower and other residential buildings in the works as well as new arts institutions, foot traffic will increase dramatically, and long-term plans include a full-fledged café, live music, and after-hours performances, all of which can generate revenue and solidify TFANA as a community cornerstone.

Meanwhile, “other” performances—pre-show education events, backstage and walking tours, park lectures, cabaret performances, and late-night short musicals and plays—declined, as did the number of (and attendance at) staged readings and workshops. Warehouse Theatre’s Savas says he’s not surprised that theatres have to cut back if they can’t afford to pay people to run these events and can’t spread their staffs any thinner.

“We had to put our reading series on hiatus,” Booher says, explaining that PCPA lacked the staff and funding for it. “We love it and the audience loves it, so it’s the worst kind of decision to make.” (The theatre did, however, get a $300,000 bequest for new-play development.)

Still, most theatre leaders said that apart from readings, “other” performances remain vital, not so much for the revenue they generate as for the “connecting line from the mainstage to Main Street,” Warehouse Theatre’s Savas says. “If you take the long view, they are successful.”

He says community enrichment adds value for subscribers and donors: When they get to see what a stage manager does or how the lighting board works, they better understand the cost of their tickets. And when they participate in a wine tasting and vote on which wine should be sold, they feel like part of the theatre community, and the theatre can raise the price point because the voters feel like they are getting a quality product. “It helps build better relationships and turns subscribers into donors into legacy givers,” Savas says.

Albert says he uses Court’s University of Chicago connection to bring in scholars and professors to add insights into the works they are staging. “Our patron group embraces these intellectual resources,” he says.

Kralicek has added a new Friday night special at Unicorn this year with guests ranging from a puppeteer talking about his work in the play The Oldest Boy to a local lama discussing Buddhism. Combining these opportunities with the ability to serve food and cocktails before a show “turns a night at the theatre into a full-fledged event,” he says.

Cosley says they created a post-show cabaret at Ensemble Theatre by simply letting the artists working with the theatre take it over and stage a talent show. “It was well received, and we’ll do it again,” she says.

Pittsburgh Public Theater’s Pappas agrees that theatres should seize every opportunity; his theatre’s offerings range from lectures to art exhibits to cocktail hours. The goal is to always keep the theatre lit and to bring in younger locals for whom “theatre is not part of their vocabulary.”

“It creates a sense of community and excitement, a sense of the theatre as a destination,” Pappas says, adding that a twentysomething might stop by after Othello finishes to see a rock band and to have a few drinks, but that the visit might inspire him to check out Othello the next night. “It’s not a solution to our budget issues, but it is the solution to an even tougher problem—building an audience for the future.”

Stuart Miller is a New York–based freelance writer.

Size Matters

In their Profiled Theatres overview, the Theatre Facts writers highlight differences between theatres of different sizes: The largest theatres (those with annual expenses over $5 million) covered more expenses with subscription and total ticket income; investment income; and total earned income. They filled a higher proportion of overall seating capacity; spent more on production payroll and less on occupancy; and were most likely to own their spaces. On average, they ended the year with a positive Change in Unrestricted Net Assets (or CUNA, which represents the theatre’s bottom line), but still had critically negative working capital (unrestricted resources available to meet day-to-day cash needs and obligations).

Midsized theatres ($1 million to just under $5 million budgets) comparatively earned more from education/outreach programs, spent less on physical production expenses and more on administrative payroll, and had the highest subscriber renewal rates. They tended to operate under a working capital shortage, but end the year with positive CUNA. While the largest theatres are almost all urban, midsize theatres are more likely to call suburban and rural communities home.

Smaller theatres, with budgets under $1 million, relied more on contributed income—especially foundation and government funding—than larger companies. The smallest theatres filled the fewest seats with subscribers and had the most trouble retaining that group. They spent larger portions of their budgets on artistic payroll and general management costs, and earned much less from investment instruments. The larger of these theatres ended the year with negative CUNA, on average, and slightly negative working capital, while the smallest of these theatres ended with positive CUNA, on average, and operated with positive working capital.

Workforce and Economic Impact

The Theatre Facts report delves into the issues facing all theatre companies across the nation, but it also underscores the vast role all these not-for-profits cumulatively play in American life. In 2014, the estimated Universe of U.S. professional not-for-profit theatres, which includes organizations large and small, staged 216,000 performances of 22,000 productions, bringing to life the endeavors of 90,000 professional artists. Nearly 33 million audience members saw these works, including nearly 1.5 million season subscribers.

Approximately two-thirds of the theatre workforce was comprised of artistic personnel, 22 percent was production/technical, and 11 percent was administrative.

The fiscal crunch following the Great Recession was doubly harmful—theatres laid off employees, which in turn, hurt the theatres, says Sarah Horton, managing director of Artists Repertory Theatre in Portland. Once she sent staff from marketing and development packing, “we had no infrastructure and were hogtied in terms of solving our problems. In retrospect, it was a terrible move.” Horton has since made marketing and development hires, and just received foundation funding to hire someone to oversee new-play development.

“You do need to spend to support your art, which I now appreciate,” says Michelle Mulholland, managing director of Golden Thread Productions in San Francisco, adding that they just hired their first dedicated marketer “and hope to see equal return” in increased ticket sales.

“You have to invest money to make a theatre work,” agrees Michael Maso, managing director of the Huntington Theatre Company in Boston. He cut 15 percent of his staff in 2009 but has more than restored that since then. “It takes an amount of infrastructure to support artists and bring in audiences and raise the resources to pay the bills. We are producing eight plays per year and more than ever we need people.”

Beyond the artistic and societal contributions, the not-for-profit theatres, therefore, also had a tremendous economic impact. Through direct payments for goods and services and the employment of 135,000 artists, administrators, and technical production staff, the theatres contributed more than $2 billion to the U.S. economy. And, since those employees spend money in their communities and contribute to their tax base while the theatre audiences also often spend money on babysitters, parking, drinks and dinner, the report makes it clear that the economic impact on local communities goes far beyond those measurable figures.