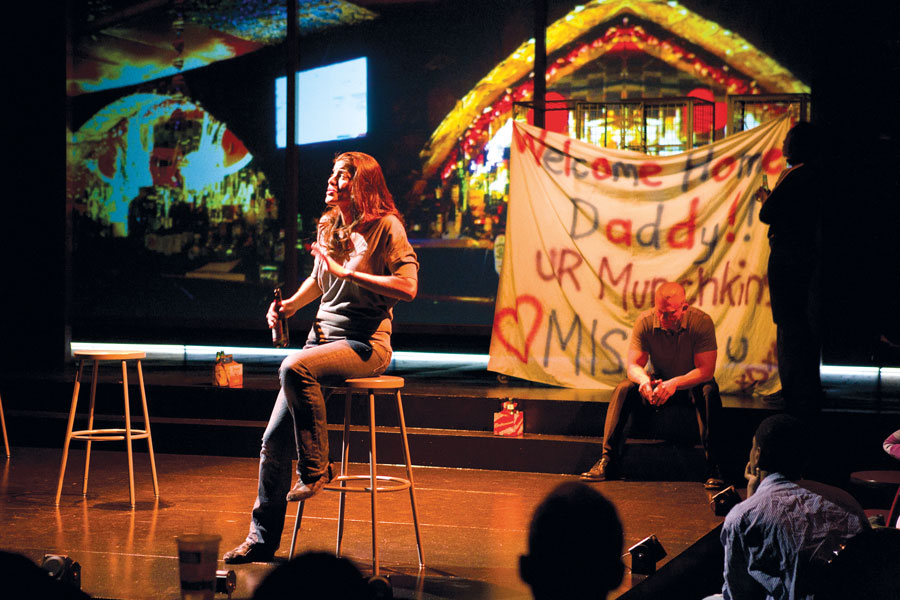

Neither has served in the military, but both Bryan Doerries and KJ Sanchez have felt called to serve in other ways: Doerries with his company Outside the Wire, which since 2008 has toured his stripped-down translations of Greek tragedies to military bases around the world, including at Guantanamo Bay (AT, July/August ’11), and Sanchez with ReEntry, a docutheatre piece she created with Emily Ackerman based on interviews with veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan (in the same AT issue). Both have since branched out to do similar work in other contexts: Doerries with healthcare workers and prison guards, and Sanchez with pieces about equity in the arts and most recently the legacy of brain injuries in professional football (X’s and O’s: A Football Love Story at Berkeley Rep, coming soon to Baltimore’s Center Stage; AT, March ’15).

Doerries’s new book about his work, The Theater of War: What Ancient Greek Tragedies Can Teach Us Today, will be published on Sept. 22 by Knopf, along with a volume of his translations of Ajax, Women of Trachis, Philoctetes, and Prometheus Bound, titled All That You’ve Seen Here Is God. A star-studded 10-city fall tour to mark the book launch begins Sept. 27 at the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

Some months ago, Sanchez and Doerries, who are friends and colleagues, met for drinks at Soho’s Ear Inn to talk shop about military culture, the machinery of tragedy, and why talkbacks are an obscenity.

KJ Sanchez: What I love about your book is that it covers all your work, not just your work with the military, but how all of these plays can serve as palliative, as healing, as a reflecting pool and a conduit to important, life-changing conversations we don’t seem to be able to have until we have that play that can ignite them. What the book can do is become a lighthouse for a lot of people who want to do this kind of work.

Bryan Doerries: I hope so. I certainly hope so.

Sanchez: I have to make a confession. When I first saw your presentation on an Army base, I got really emotional—and that was before the actors even started. I got emotional with your introduction. You get up there and say that in your marrow you are committed to this conversation that is about to happen. It’s clear how personally dangerous it is, how professionally dangerous it is, and you lay it all out on the line. The way that you introduced Ajax—the way you set the stage for who Ajax was and what his friend Achilles meant to him, and the loss of dignity and humanity that Ajax suffered when Achilles’s shield is given to Odysseus instead—this was all in your introduction, and I was already just completely engaged.

And I was so happy to see that you put all that personal investment in the book, too. You had talked to me a little bit about losing your girlfriend Laura. Obviously, losing someone you love is a key moment in anyone’s life, but I didn’t realize how that really triggered what you would do for the rest of your life.

Doerries: You know, you make one decision in your life: I’m going to care for a person; I’m going to put it all on the line and see where this leads. I’m going to face death, I’m going to face suffering. And it just continues to open world upon world upon world. I owe all my work to that experience, and it keeps unfolding in all these ways that I could never expect. Laura died on March 20, 2003, in the East Village in our apartment, and a year ago, on March 20, I found myself sitting in an office at Sloan Kettering being asked whether we’d bring Philoctetes to this cancer hospital. We did five or six free performances, engaging these oncologists in open discussions about death and dying and being in the presence of suffering, using this ancient play as a catalyst. At the end of that, the head of surgery’s wife comes up to me and says, “We’d like to ask you to be our commencement speaker this year for the surgical oncologists.” I always thought I would get a high school graduation, or you know, the Rotary Club, but to be given the opportunity to speak to 75 of the top surgeons at the top training institution in the world for oncology was a huge opportunity.

So standing in front of these doctors, I hit them really hard—I talked a lot about Philoctetes and about Hippocratic medicine, the limits of medicine in the ancient world and how there was wisdom in conceiving of a medicine with limits. I had no idea if it would land. And then, at this black-tie event at Cipriani, one by one these doctors, these chairs and chiefs of the program, came up and said, “That really touched me.”

What I’ve learned over the last six years or seven years is that sometimes it really takes an outsider to change the culture of an institution, whether that institution is the theatre or a hospital or the military. The only way to stand in front of an audience of a thousand Marines who are thinking about the ways they could disembowel you, who are resentful at the fact that you’re there telling them about Greek tragedy and they’ve been “volun-told” to see it—the only way to stand there with any confidence in my opinion is to revel in being the outsider. You don’t have to be hyper-masculine; you don’t have to be accepted or even be liked by them. You just have to deliver this thing to them.

Sanchez: And you have to be willing to listen. That is very, very clear with what you do. Even if what you ask them is, “So tell me how we got it wrong,” then that opens the door.

Doerries: That’s the best!

Sanchez: That’s the best question, right?

Doerries: I know it’s working when two things happen. One is when the lowest-ranking member of the community for which we’re performing, the food service worker in the prison, the private in the military, the palliative care hospice nurse in the hospital setting, stands up and speaks the truth of his or her experience in front of the highest-ranking members. The second way I know it’s working is when people talk about how much they hate the experience, and they can openly do it in their own words. It becomes all the more validating, after the person who said, “This is the fucking most pretentious thing I’ve ever experienced,” for someone to say, “This is the most life-changing thing I’ve ever experienced.” I find myself grinning from ear to ear when people stand up and say, “This is bullshit.” Because we’ve created a place where that can be said. I mean, where else can that be said in these regimented hierarchical environments, you know? I mean, it’s okay for us to get up and say it at the Public Theater, but to say it where your job is on the line?

Sanchez: Wouldn’t that be fantastic if we could have more of that immediate feedback loop in the American theatre at large? Because the only way we have feedback is audiences can give thumbs up, thumbs down, reviewers can talk about what they liked or whether the writing was successful. This isn’t about, “Do you think we’re good playwrights?” It’s: I’m going to do my very best to share, to tell you this story in an artistic, human way. Then I want to hear whatever you have to offer, all of you.

Doerries: When we move the needle and audiences are buzzing because they’ve been touched in some meaningful way—not necessarily explicitly about a social issue, but touched as human beings—we have an opportunity to do something with that energy. Yet 99 percent of the time, with great speed and efficiency, we suck the life out of the possibility in that audience. We do that by having a dramaturg come out and give a lecture; we do that by having people who share our political beliefs come out and congratulate us for having those beliefs; we do that by, worst of all—with all due respect—having the artists come out and talk about process. That’s the most soul-deadening thing you can do after an uplifting experience in the theatre. Instead, this model, which I know you subscribe to—

Sanchez: Well, we outright stole it from your design when we did ReEntry at Center Stage, then at Actors Theatre of Louisville. We did exactly what you do: Immediately after the performance, panelists came up. With ReEntry it was a veteran, a spouse, and either a chaplain or a mental health worker. And their job was to give their first-blush personal response to the play. It can be, “This play made me angry,” “This play was exactly my story,” “This play made me question how I’m going to talk to my husband,” or, “What you didn’t get in the play was this.” And then a town hall discussion. It’s completely different than having the actors come out, and then the audience has to be nice and say, “What was it like to be that character?”

Doerries: It’s to the point where the word “talkback” has become an obscenity to me. Not because the word isn’t descriptive of what we should be doing—we should be talking back. It’s an obscenity because we have turned it into a manifestation of our most banal, most unimaginative impulses in the theatre. Theatre is a psychotropic experience; it changes us biochemically. It puts us in a different state of consciousness. And once we enter that state of consciousness, something can happen.

Sanchez: We need to coin a new phrase—“talk-across.”

Doerries: Yeah!

Sanchez: Instead of a talkback, you know?

Doerries: I mean, right now it’s really a “talk down.” It’s about, how many different ways can we condescend to the intelligence of this audience? Until we’ve deadened the possibility we’ve created. The model that we use and that you have innovated on in your own way—I do think it speaks to the ancient model from which these ancient texts derived and evolved, which is that a city would empty all of its courts, its places of work, its places of worship, and send one third of its population to a theatre, and 17,000 people would sit according to tribe and rank and watch plays that were explicitly speaking in some way to fundamental human experiences. Not as sheer entertainment and not as therapy per se, but as a religious experience—a rite, something that is sacred.

Sanchez: I get a little squirrely when I hear the word religious, but my version of that is about bearing witness.

Doerries: If I had one word to define this work, it’s permission. How many different ways can we give you permission—you, the audience—to speak the unspeakable? To acknowledge the thing that you buried deep and denied? To face death? To collectively acknowledge our shared humanity, and also, most importantly with the tragedies we perform, to acknowledge the limitations of human compassion? The note I give actors before they go onstage is: “Make them wish they’d never come.” The reason I say that is because if we push an audience to a point where they wish they weren’t there, and in some way they’ve been trapped—whether they’re “volun-told” or it’s socially unacceptable to walk out, or it’s a place without an aisle—that then we can create this moment where we can actually interrogate why it was so difficult to be in the room. I used to think it was all about empathy, but for me it’s much more about shared discomfort.

Sanchez: Right. You know, we use the phrase “compassion fatigue” a lot, when we’re not really all that tired of being compassionate. But you are actually dealing with communities, with doctors and hospice workers who are facing death every day, dealing with a military on their 8th, 9th, 10th deployment—you are dealing with people hitting the wall.

Doerries: Absolutely.

Sanchez: And you’re saying to the actors: Throw the wall back at them and then somehow you bust through together.

Doerries: Yeah. Push it past them, past what people in the room can handle. I mean, most of our audiences are red state audiences; they don’t share a lot necessarily in common with the actors or with me in terms of our values, our political perspectives. But if we share nothing, at least we share that we were uncomfortable.

Sanchez: That is such a great place to start. That’s the base of human experience.

Doerries: So if you want to have a conversation about abortion, if you want to have a conversation about war, if you want to have a conversation about traumatic brain injury, start with a portrayal of human suffering first, push the audience past its ability to hear it, witness it—and then have the conversation. I guarantee you it won’t be a shouting match of people trying to savage each other with ideology, because we have moved the audience from one cognitive space to another, and it creates the opening. I see it every place we go, from San Francisco and Cambridge and D.C. to the most rigidly conservative audiences in the middle of the country.

Sanchez: Ajax was your first project; you used that play as a way of talking about battle fatigue, post-traumatic stress disorder or post-traumatic stress—depending on who you talk to, because some folks don’t like the term “disorder”—the spousal experience, and obviously suicide. Talk us through a couple of the other pieces that you cover.

Doerries: Concurrent with the development of Theater of War, I also developed this project, presenting readings of Prometheus in supermax prisons. At first I thought we were going to perform it for the inmates.

Sanchez: But then something even more interesting happened.

Doerries: After trying to get into Rikers Island and getting very close but not making it, I met a social worker there who said, “Listen, I have a cousin who is the director for corrections in the state of Missouri, and he might just be crazy enough to allow you to come in with Prometheus Bound.”

Sanchez: It’s always about meeting the one that’s crazy enough. Or desperate enough. I once had at a Marine Corps retired general say to me, “We’re desperate now—we’ll try anything.” That’s why he was all for bringing theatre into the military.

Doerries: Yeah, God bless the military. They’re not like foundations that need metrics before they try something. They have a problem the scale of which is so large, and for better or worse, they have such a large portion of our gross domestic product and our tax dollars, and you and I came in at this moment where they were trying everything: They were trying sand rock gardens, they were trying equestrian therapy, they were trying dolphins. Greek tragedy or documentary-style theatre actually seems relatively middle of the road when you think about all the things they were trying. They were throwing them up against a wall and seeing what stuck.

Sanchez: So back to: You met this woman who had a cousin who might have been crazy enough to try this.

Doerries: Yeah, so I call the cousin and he immediately returns my call. His name is George Lombardi, he’s the director of corrections in the state of Missouri. And he says, “Listen, I really like your idea. We have some programs already for prisoners, but what I think maybe would be more valuable is if you came in and did the performance for corrections officers and other people working in the prisons. No one ever does anything for them, we have very little psychological services for them, and they do time eight hours a day and live in these hellish environments, and, you know, maybe something could happen.” The more I thought about it, I thought, well, there’s not closer analogue to the military, where I knew the project was really working, than the sort of paramilitary apparatus of those who work in prisons. They have rank, they have file, they report their surveillance, there’s punishment. To a certain extent, there’s no difference between a barracks and a hospital and a prison. They’re all systems of rigid hierarchy, of discipline and punishment. And Prometheus is about discipline and punishment! It’s about living within this hierarchical structure.

Sanchez: I was very struck with how many guards identified with Prometheus, and see themselves as part of the prison industrial complex in a way that really surprised me.

Doerries: Theatre gives us the opportunity to step back from the roles we’re all playing, to acknowledge the archetypes and look at them more objectively. Everyone who works inside a prison is aware that a very thin barrier separates them from the people they have power over—that only grace separates them in many ways. Many who work in prisons come from the same socioeconomic background, the same neighborhoods, the same classrooms, the same gangs, as the people who are in the prison themselves. So that came out immediately in the discussion of Prometheus Bound after the first performance we did at a supermax prison for the guards: “I’m Prometheus; I’m the one who can be punished for showing compassion to the people that I’m guarding,” or, “I’m the one that if I get a DUI will get a mandatory sentence of five years or more,while you, because you can afford a much better lawyer, Bryan, will get off.”

You know, all of these communities that we go into are communities that practice a kind of emotional detachment at the center of their work, whether it’s surgeons or soldiers or guards or corrections officers. And theatre has the capacity to create a safe space for them to let down the barriers—to allow the Trojan horse of Greek tragedy in and to feel something, and to do it in a public, and even in a performative way.

One of the things I’ve also learned from this work—and this is the center of your work in every way—is that we need mediation. Theatre is mediation. Like, if I allowed myself to feel the things it would be appropriate to feel from the walk from here to the subway in relation to people that I saw on the street, I would be destroyed. So I practice this clinical detachment as well. I need to be wrested from it, for it be wrenched away from me, and the shock of being in the presence of a believable portrayal of human suffering, with an amazing actor delivering it, can do that.

Sanchez: I understand why some doctors and others become desensitized; it’s a survival mechanism.

Doerries: Certainly. It’s not adaptive to be crying when bullets are flying at you, or when you’re in an ER and you’re having to cut open someone’s chest. But there has to be a sanctioned place to feel those things, and the theatre was that sanctioned place. This is not some fanciful fabrication. It was the place where everyone stopped working, they came together, and they purposely put themselves in front of an experience that would elicit these feelings. In a century in which 80 years of that century was spent fighting war—in the latter half of a century in which a third of the Athenian population had died, if we believe Thucydides—there is no one in the Athenian audience who wouldn’t have known the screams of these characters. There was no one in the audience who wouldn’t have understood that first- or secondhand. So for the last six years, the experiment for me has been: What do we do when we take these ancient stories, which I think are a technology designed for very specific audiences that had lived these experiences—

Sanchez: The original apps, is that what you’re saying?

Doerries: Yeah, I think of them more like external hard drives. When you plug them into an audience for which they were designed, the plays know what to do and the audience knows what to do in return. Like when you transplant a kidney, and before you finish suturing it into the new body, the urethra is pumping urine. There’s something about these plays that are living, breathing, organic technology for delivering a very specific experience.

But this is where your work comes in; there are so many people who are suffering and need an intervention of this nature for which there is no classic text and something needs to be devised.

Sanchez: Right, American Records’ mission is to make work that chronicles our time, and work that serves as a bridge between people. So my job is to listen to a particular community, to a particular story, and then what I do is I frame it in a palatable way. I’m a huge fan of documentary films, but documentary theatre does something very different, similar to what you do, which is that it allows us to bear witness together. So I start with a subject, something that I find burning and interesting. This is going to not make any sense, perhaps, but I pick subjects I don’t understand yet what I feel about. That’s been my guiding principle for the last 10 years: that what I think and feel about a situation has nothing to do with what I’m trying to do. In fact, I’ve turned down stories and projects—

Doerries: Where you have a lot of skin in the game?

Sanchez: Yeah. I’ve been asked to do something about immigration, and it’s like, no, I know how I feel about that. Then it becomes agitprop theatre.

Doerries: That’s a really important distinction. Because I think theatre that wears its politics on its sleeve alienates the very audience one would hope to engage. It’s not about the opening of meaning, or discovery, it’s about the closing of meaning and discovery.

Sanchez: I took some heat from my colleagues with ReEntry. I had a handful of people angry at me because I didn’t make an antiwar play. They thought that Emily and I made a pro-military play because I didn’t end the play with “war is bad.” I ended it with, “You know what? They’re still going back, and they couldn’t give a shit what the war is about.”

But all of these stories are incredibly emotional; the stakes are unbelievably high. For the last 9 years I’ve been promising myself a nervous breakdown. I keep saying that when I’m interviewing somebody, my job is not to let them know how I feel about anything. I’m on board for wherever they’re going to take me. So I don’t cry; I set aside all of that. Someday I’m going to go away, find a shaman, get into a sweat lodge, and let it all out. And I’m sure this happens everywhere you present: There’s a line of people who want to tell you their story, right? I find people who don’t feel comfortable talking in front of the group, they pull you aside.

Doerries: Yeah, definitely. It goes on for hours.

Sanchez: Where do you put that?

Doerries: It just gives me energy. It doesn’t take away. What I see night after night in the audiences when we perform is a palpable sense of relief.

The first question I ask all audiences is: Why do you think Sophocles wrote these plays and staged them for his community? What was he trying to say—what was his objective? Of course, the subtext of that is, How did this make you feel? And “how does this make you feel” is a question I wouldn’t want to be asked myself. So I say, “Why did Sophocles write this play?” I’m making it sound like a quasi-academic question. At one of our first performances, at an artillery base in Germany, this junior-enlisted soldier immediately raises his hand and says, “I think Sophocles wrote Ajax to boost morale.” And I say, “What’s morale-boosting about watching a great warrior lose his best friend, come unglued, attempt to kill his commanding officers, and ultimately, against the pleading of his wife and family, take his own life?” Before I could finish the question, the soldier shoots back, “Because it’s the truth.”

Sanchez: One of the best compliments I ever got was a lance corporal who walked up to me and said, “First of all, ma’am, I would like to say, I’m very glad this did not suck. And secondly, it’s good to know I’m not alone.”

Doerries: That’s terrific. I was at Camp Pendleton, and a Marine came up to me and said afterward, “Hey, sir, I liked your little skit.” I was like: You’re right, it is a skit.

Sanchez: We’ve talked about this before, but you and I have both noted the difference in communicating with military leadership versus leadership in the American theatre.

Doerries: Oh yeah.

Sanchez: I can get a general to return my emails and my phone calls, but there are a good number of artistic directors who don’t have the time and ability to communicate well.

Doerries: Well, for what it’s worth, maybe the general has more resources.

Sanchez: Yes, that’s a good point. One of my favorite things that Anne Bogart ever said to me was a little advice she gave when I was becoming a director. She said, “You need to figure out if you’re a person who’s round on the outside and square on the inside, or square on the outside and round on the inside.” The military and medical and service communities that we work with are very square on the outside. You get a response—either, “No, thank you,” or, “We’d like your play at our base, please advise.” Done. But in the world we traffic in, because of all of our creativity, we’re round on the outside, so it’s more difficult to communicate, to be hard when we need to be hard. Do you know what I mean?

Doerries: It’s actually been a big revelation for me. Would I rather deal with academics, people in the theatre, foundation people—or with people in the military to try to get something done? No question who I’d want to work with. There’s something so remarkable about the efficiency. There are a lot of inefficiencies, obviously, in the military, but if you give people in the military two pieces of paper with a quick proposal, and maybe one phone call later, it’s executed, usually flawlessly—maybe a little too literally. If you work in the theatre or with academics, you have 20 phone calls. Maybe it’s part of the culture from the get-go, or maybe it’s just when you’re facing life-and-death issues, you don’t have time for all the bullshit. You attack problems more efficiently. There’s something deeply refreshing about it.

Sanchez: Does it make you crazy when well-intentioned people say, “You know, you should hook up with the USO”? That makes me crazy!

Doerries: No. We did partner with the USO on a quarter of a million dollar grant, and they were great partners, and they have an enormous reach.

Sanchez: But it’s about, “Let’s entertain the troops.”

Doerries: It’s different. So the other person person that should be sitting at this table is Adam Driver, whose organization Arts in the Armed Forces, of which I’m on the board, espouses that specific approach. He was in the military, the Marine Corps, he went to Juilliard, he’s had a successful career, and he feels that people in the military deserve not to be condescended to with what passes for entertainment. They deserve to be uplifted and challenged, and so he doesn’t do plays that are explicitly about the military—he does John Patrick Shanley, and he allows the audience to have its own human response. They’re not about discussion, but they’re about raising the bar and saying, you know, it is a form of service to go into these communities and bring something that actually is challenging or uplifting, rather than to you know, simply entertain.

Sanchez: Yeah. Isn’t it cool now that we have a tribe?

Doerries: Yeah, there’s a tribe.

Sanchez: You mentioned Adam, and there’s also Paula Vogel.

Doerries: Paula Vogel, and there’s a whole bunch of others.

Sanchez: What’s so fascinating about her is that early in her life, her day job was as a secretary for the Navy.

Sanchez: And now she’s offering herself to do workshops whenever possible for veterans, to teach, to the give them tools to write their own plays.

Doerries: And she’s cultivating the talent of this next generation of veteran writers—Maurice Decaul, all these other writers she has taken a personal interest in. She’s created space within TCG for veterans, for theatres to come to a different orientation, to what it would meant to actually do something that might move to people socially with regard to veterans.There are a lot of people in the space now, and as far as I’m concerned, the more the merrier.

Sanchez: I agree.