It is exquisitely painful to be writing in the short-prose form for Mark Rucker…again. It was one of his favorite things to make me do. On long car rides, he would drive and I would read aloud and write on command. Our prose only resulted in incomplete picaresques, a fragment of a faux-Moliere called School for Fems, and one filthy full-length solo piece which Mark directed at Josie’s Cabaret in San Francisco called “Dr. Scheie’s Traffic School.”

One road trip in 1989 went from Santa Cruz to New Haven via Las Vegas, Quebec City, Provincetown, and Fire Island. Several were Key West round trips. Another was by bus and tramp steamer from Jerusalem to Mykonos via Haifa, Cyprus, and Crete. We were in the middle of creating another one-man show by Peter Sinn Nachtrieb; we had finished a June residency at Berkeley Rep’s Ground Floor in preparation for a 2016 opening at Theater Artaud. Mark was to have picked me up for rehearsal the morning he died.

In and around those two plays were his big, brilliant productions of the world’s dramatic masterpieces. I was lucky enough to act in some of them. In James Magruder’s translation of Imaginary Invalid at Yale Rep, wildly ahead of its time, Veanne Cox appeared as Hillary Clinton; the New York Times loathed it. I played Mistress Quickly at Shakespeare Santa Cruz in 1994 when Mark and I comprised the artistic directorship. He attracted the very brightest of designers: Kevin Adams, Mark Wendland, and Katherine B. Roth created a trailer-park Windsor, and I wore a mustache and halter, and was unlocate-ably trans. The Birkenstocked Santa Cruz bourgeoisie chased us naked and bleeding up Highway 1 to San Francisco. He let me play Mercutio, a mourning gift, opposite Adam Scott’s Romeo at Cal Shakes, and later Feste, playing “Don’t Cry For Me Argentina” on a trombone while rollerskating on a wet rake.

Like many people who ultimately realized that they were in fact truly loved by Mark, I initially thought he couldn’t stand me. That glare. The lack of affect. The big brown eyes filled with what was certainly silent, superior judgment, and a little bit of reined-in disgust. Mark sometimes expressed unbridled joy by a scowl softening into a frown. He himself called this involuntary accidental veneer “malign in repose.”

Then, almost overnight, we became Epic Best Friends. I was in downtown Los Angeles doing my first Equity gig, playing Damis in a 1986 Tartuffe starring Roy Cohn, Lucille Bluth, and Bride of Chucky (respectively Leibman, Walter, Tilly). Mark and I went out every night after the show for months, visiting every gay bar in Los Angeles County, a pursuit we called “indexing.” We drank. We developed a vocabulary so rococo I can’t even. There will be much written, I guess, about his immaculate sense of style, but what actually made him smile was the inverse of all that good taste, that for which we coined the adjective “swappy.”

One day in San Francisco outside the Castro Theater where Mark’s film Die Mommie Die! was screening after its premiere at Sundance, Armistead Maupin told me that Mark had called me his best friend. I could not have been more proud. Indeed: Epic Best Friends.

Danny Scheie

Actor

Costa Mesa, September, 2015

Mark and I met when he directed my play Hold Please at South Coast Rep a million years ago.

One night in tech, I was being a real asshole. An actress wasn’t getting her lines right, and Mark insisted on being calm, patient, and understanding with her. It was infuriating. Obviously he didn’t care enough about the World Premiere of My Play to get angry and push. These were my thoughts as I gathered up the train of my imaginary gown and stormed out of the theatre in tears on Monday, September 10, 2001.

The next morning, something slightly more important than the World Premiere of My Play happened. I called Mark, feeling foolish and ashamed of myself. I wanted to go give blood to people at Ground Zero. Remember how we all wanted to give blood? Even though no one needed it. I didn’t see the point of doing my play any more. I wanted to quit. I was scared and confused. A total mess.

Mark wasn’t. He was calm, patient, and understanding. Just like at tech the night before.

“Annie, you’re a writer. This is what you have to give.”

I had underestimated Mark. His refusal to push didn’t come from indifference. It came from faith in the process. Mark had profound respect for his collaborators. He trusted them enough to give them space to get there. He believed in all of us, and in the work we were doing, and he made me believe in it, too. With a gentle hand, he guided me back. It was the first of a hundred times he would do that for me.

For so many of us, Mark was an oasis of calm and reason in a chaotic world. Even when surrounded by brittle egos, he remained stable, generous, and understanding. In our 15 years of friendship and collaboration, I never once saw Mark lose his patience or respond to a difficult situation with anything but grace. He was so giving, insightful, and goddamn dependable… I depended on him. Lesser person that I am, I needed him to guide me.

And now he’s gone.

A few years ago, my beloved dog Trucker was sick and near the end. I called Mark in despair. I told him that I’d cooked her a hot dog and put it by her bed. She just turned away. I couldn’t face the decision to put her down. I tried to make him do it for me.

“Tell me what to do, Mark.”

“I think she just told you.”

(There it was again. That refusal to push. The calm, steady hand on my back. Listening. Trusting. Guiding.)

“But I’m not ready.”

“I think she is.”

But I’m not ready.

Annie Weisman

Playwright

I met Mark Rucker at UCLA in 1979. I was in grad school and he was an undergrad in the School of Theatre. He was a beautiful young man, a grownup Tadzio, but unaware of his own beauty. Mark was quiet, dreamy, and possessed of an encyclopedic knowledge of theatre and film. He loved architecture, fashion, food, all kinds of Americana, but especially the great Hollywood classics of the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s. He seemed to me to have a profound awareness of what was important to living consciously. He saw beauty everywhere.

We became friends and colleagues very quickly—Mark assistant-directing on my student projects, me sort of advising on his directing projects. Through Mark, I began to understand Los Angeles and so much of American culture. Our home and our work was utterly infused with his passionate and effortlessly witty sense of style.

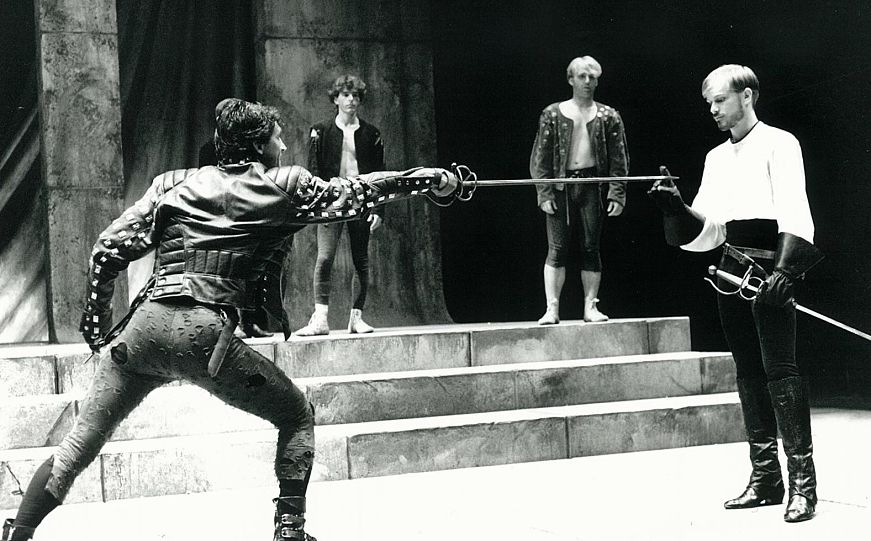

On graduating we—along with a happy band of grads—rented a pace on Gardner Ave. in West Hollywood, where we conducted acting workshops with all our favorites from UCLA and began to produce work, both of us directing: Moonchildren and Romeo and Juliet, for goodness sake, in a tiny room for audiences of 40! We got reviewed. Favorably. It was organic, all-consuming, and so much fun. We had formed the basis of an acting troupe, and he led the company to a new space in downtown L.A. on Skid Row and called it City Stage, where he produced, with many dear friends and allies, a stream of cutting-edge, brave, thoughtful work. He was by then in his early 20s.

I got a job at UC Santa Cruz in 1982, and the following year I asked Mark to assist me on The Merry Wives of Windsor, my first production for Shakespeare Santa Cruz. We later talked often about what a life-changing experience that was for both of us. I soon became artistic director; he continued as artistic director of City Stage, and pretty quickly I asked him to direct at SSC. He then proceeded over the rest of the ’80s to direct a truly amazing, visceral, hilarious, eclectic, deeply felt, and uniquely stylish body of work: Company, Romeo and Juliet, Damn Yankees, Titus Andronicus, Macbeth, King Lear, and, of course, an utterly outrageous, beautifully designed, giddily performed trailer-park Merry Wives.

During this period, he found his voice as a director of classic texts, contemporary works, and musicals, and as the quietly confident and loving guide for so many actors. They adored, trusted, and followed him through anything.

Now I realize what an amazing time we had at Shakespeare Santa Cruz in the ’80s and ’90s. For Mark it was a time of unbridled, fiercely energetic creative activity. I remember a particularly challenging rehearsal of Richard II, though. Mark was assisting me. It was a rehearsal filled with spirited and, I thought, thrilling discussion. Not much staging happened. At break, I asked Mark what he thought, hoping for a pat on the back. “You talk too much,” he said. I am so grateful for that comment—for his mind, for his grounded perspective, his honesty, his wicked humor, and finally for his love.

In 1989, before he was 30, he was accepted into the Yale School of Drama and went on to become, as so many people now know, one of the most beloved and respected artists in American theatre. But for a few precious, shining years it felt like it was just us, even though there were always many other gorgeous fellow travelers.

He was my best friend, my most trusted and beloved colleague, my younger brother. His absence is a stone in my chest.

Oh, wait. I can hear him whispering in my ear.

Michael Edwards

Artistic director

Asolo Repertory Theatre

Mark Rucker was a gifted guy. Of course, as statements go, that is what is known in literary circles as a masterpiece of understatement. Mark was a prodigiously talented director; a marvelous raconteur; a giggling gossip; a gleeful connoisseur of camp, kitsch, and gorgeously tattered Americana; a snappy dresser; a dedicated son, brother, and, perhaps dearest to him, uncle. He was a leader; a visionary; a dreamer; a cock-eyed sympathist, who, like Terence, counted nothing human foreign to him. He was a devotee of beauty and a spirited guardian of its residence in the beholder’s—any beholder’s—eye. He was a diviner who unerringly located subterranean springs of potential in every collaborator from the most seasoned professional to the greenest student.

Oh, forget the fucking metaphors. At virtually everything he set his hand to, he was extraordinary, and don’t even get me started on his humility.

But all these things pale in comparison to his greatest gift: Mark Rucker had a positive genius for friendship. That is what makes writing about him, itemizing his excellences, so numbingly insufficient—the weight of the responsibility and the realization that you’re just a representative of so much genuine grief in numerous hearts, of such a profound absence in so many lives, the awareness that you can’t scratch the surface of the general loss.

Each and every one of us in his orbit felt the gravitational pull. He shone, lavishing on all a very particular-to-us affection, and the generosity of his attention kept us warm and well. Ah, metaphor keeps breaking through! Suffice it to say, no one I have ever known personally has inspired such widespread admiration and, there is no other word for it, love. Even in his death he is bringing us together again—over drinks, over dinner, over email, over the phone, over and over and over. And on it will go.

Living on in the love he not only inspired but actively cultivated—that is so Mark Rucker.

Catherine Sheehy

Chair of dramaturgy and dramatic criticism

Yale School of Drama

Excerpted by from my piece for the YSD Alumni Magazine

With respect to his life in the theatre, Mark Rucker literally grew up at South Coast Repertory. Born and raised in Orange County, he attended SCR productions as a schoolboy, and while in high school he ushered at our Third Step Theatre in Newport Beach. But we didn’t know about that important personal connection to the company until he directed his first production for us, Alan Ayckbourn’s Intimate Exchanges, in 1993. He would go on to direct a total of 21 productions at SCR, everything from Marivaux to Joe Orton, Thornton Wilder to Richard Greenberg. But above all he made his mark at SCR with his inventive productions of Shakespeare’s work. People are still talking about his most recent production for us, his 2011 staging of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, not to mention his transformation of SCR’s founding company members into a leather-clad biker gang for his cheeky 2002 production of Two Gentlemen of Verona.

Actors loved working with him. He had a gentleness of spirit to go with an unassuming manner. As a director he was both self-assured and genuinely collaborative. He cared deeply about everything he worked on and, partly as a result of that, he drew the very best work from his artistic collaborators.

Midway through his 20 years of work with us, in recognition of his many contributions to SCR’s artistry, we named Mark one of only a handful of associate artists of the company—a distinction he holds to this day. When he moved north to become the associate artistic director of American Conservatory Theater, it became difficult for him to return to his first artistic home, but we never stopped thinking of him as family. All of us who had the pleasure of working with Mark at SCR mourn the loss of a gifted artist and friend.

David Emmes & Martin Benson

Founding artistic directors

South Coast Repertory