If Bill Rauch’s reign in Oregon were a Shakespeare play, it wouldn’t be a tragedy or a comedy, or even one of the monarchical histories. It would be a romance as improbable, tumultuous, and redemptive as one of the Bard’s wild and woolly later works. Since Rauch began as artistic director of Oregon Shakespeare Festival in 2007, he’s led the venerable institution on a rip-roaring ride as rife with grand spectacles, odd reversals, bitter battles, surprise rescues, catastrophes, and miracles as dramatic as any in Cymbeline, The Winter’s Tale, The Tempest, or Pericles (a fine and fleet-footed production of which, by director Joseph Haj, happens to be onstage in Ashland through Nov. 1).

The director’s eventful eight-year tenure has thus far racked up a catalogue of highs, lows, and in-betweens: a 2014 Best Play Tony for his Broadway staging of Robert Schenkkan’s LBJ history All the Way, commissioned by OSF’s American Revolutions program; a nail-biting emergency after a beam cracked in the Angus Bowmer Theatre in 2011, sending five major productions into a tent in nearby Lithia Park while the Bowmer was repaired; an ambitious drive to diversify not only artists and staff but the theatre’s predominantly white audience and board, as well; a recent push by stagehands and production crews to unionize (negotiations are currently tied up in a labor-board review); ecstatic, even awed reviews from visiting national critics; seasonal forest fires in Rogue Valley, the smoke from which has scotched some performances at the outdoor Elizabethan Theatre.

Some of these ups and downs have been out of Rauch’s hands, but many bloom from his own ambitious, uncompromisingly inclusive vision for the theatre, which was already doing quite well—financially and artistically—when he was hired to succeed Libby Appel. Helming a $34-million theatre with 11 shows in rotating repertory running nearly year-round, and a company employing well over 600 people, would be enough of an administrative chess game for most artistic leaders. But Rauch, 53, an indomitably idealistic macher since his days as cofounder of the community-building ensemble Cornerstone Theater Company, has not been content to let OSF rest on its laurels as a unique American theatrical success story, a pristine theme park/nature preserve for the Western canon. And he certainly has no intention of leaving its famously well-oiled machinery on autopilot.

While previous leaders, including Appel and Henry Woronicz, helped shepherd the company in the direction of greater diversity and new work—for their time, progressive measures for a classical repertory theatre with Shakespeare in its name—Rauch has markedly, even radically expanded these mandates. OSF’s internship and apprentice program, called FAIR, has stepped up its commitment to nurturing the next generation of theatre practitioners, with a particular emphasis on grooming young artistic leaders of color. In contrast to his predecessors, who mostly rotated among a stable of favorite guest directors (of which he was one), Rauch has made a point of hiring at least five first-time OSF directors each season. And while the acting company was already notably diverse by the end of Appel’s tenure, it is by nearly every measure moreso, as is the OSF staff; Rauch recently told the New York Times that, after hovering between 40 and 49 percent for years, the percentage of actors of color in OSF’s company next season will be higher than 50.

Rauch’s push for aesthetic diversification, though, has been at least as company-shaking, both in principle and in practice. In addition to Western classics, including Shakespeare—whose canon the company will have completed four times in its 80-year history with Amanda Dehnert’s staging of Timon of Athens next summer, a feat they’re committed to repeating within the following decade—Rauch has made non-Western classics a regular part of the OSF diet. The first play he staged as artistic director, in 2008, was a version of the Sanskrit epic The Clay Cart; in 2012 Mary Zimmerman created an adaptation of the Chinese tale The White Snake; and next year Marisela Treviño Orta’s version of a Brazilian folk tale, The River Bride, will take the stage.

He’s also put classic American musicals into the mix. While the logistical challenges of casting and rehearsing musical theatre within a rotating repertory schedule, using performers typically selected more for acting chops than for singing and dancing, has created fresh hurdles, it has paid off with popular stagings of The Music Man and The Pirates of Penzance (both directed by Rauch), and Dehnert’s lauded renditions of My Fair Lady and Into the Woods. The latter production later toured to Los Angeles’s Wallis Theatre for an acclaimed run, as will Zimmerman’s hit staging of Guys and Dolls this season.

But no change has stirred as much excitement—and created as much internal institutional pressure, as much tsuris—as Rauch’s quixotic insistence that OSF turn itself into a prominent incubator of new plays and musicals. This has strained creative and practical resources, alternately inspired and confounded the acting company, and led to both stunning creative triumphs and inevitable spats and flame-outs.

Actually, to put an even finer point on it, what has clearly been both invigorating and difficult for the institution, as well as for the planeloads of new artists he’s eagerly invited in, is Rauch’s unshakeable conviction that none of these new initiatives—the global classics, the musicals, the new works—should crowd out the company’s well-established core competency, classical repertory work, but instead can serve as rich, invigorating complements to it. Rauch wants it all: He’d like to load the canon with fresh ammunition without retiring the old stock.

A huge poster with the word “Yes” behind Rauch’s desk is widely thought to sum up his boldly affirmative philosophy. But another three-letter word might better describe his non-zero-sum approach: Faced with a menu of enticing artistic options, Rauch is more likely to look for a way to say “and” than “or.”

OSF’s American Revolutions program, which by 2017 will have commissioned 37 new plays about “moments of change” in American history, doesn’t even represent the full spectrum of OSF’s new-play work: There are new-musical commissions in the pipeline, with funding from the Edgerton Foundation; new adaptations of novels, from Dickens to Austen to LeGuin; and an ambitious Shakespeare translation project funded by David Hitz.

But AmRev, as it’s known for short, is the hub of the theatre’s new-work activity. Headed by Rauch’s former Cornerstone comrade, Alison Carey, AmRev is 23 plays into its commissioning goal, and while 7 AmRev plays have made it to a stage at OSF—with another, Lisa Loomer’s Roe, slated for next year—Carey is eager for other theatres to snatch up AmRev shows, as Steppenwolf Theatre did Frank Galati’s E.L. Doctorow adaptation The March, and Yale Rep and La Jolla Playhouse will next do with Paula Vogel and Rebecca Taichman’s Indecent, about a controversial Jewish play from the 1920s (it’s at Yale, Oct. 2–24).

“The program is so big and there are so many plays, we don’t want them to get stuck here if we’re not able to produce them,” Carey said. “The vagaries of our season planning mean that it doesn’t necessarily reflect on the quality of the plays if we can’t produce them—it’s just we’re always looking for that specific buffet.”

Carey said that apart from a few mandates—sensing lacunae, AmRev specifically sought out plays on guns (Dan O’Brien is on that one), the environment (Idris Goodwin), and the African-American relationship to the Civil War (Dominique Morisseau)—the program has been wide open to playwrights’ interests and affinities. “My hope is that it feels less like an assignment than, ‘Hey, have a good time and we’re going to give you a bunch of money,’” Carey said.

The result so far has been a bit skewed to relatively recent history: Richard Montoya and Culture Clash’s piece about immigration, American Night; Schenkkan’s LBJ plays, All the Way and The Great Society; Tony Taccone’s Ghost Light, about the murder of George Moscone alongside Harvey Milk; and Universes’ Party People, about the Black Panthers and the Young Lords. But both Galati’s The March and Naomi Wallace’s The Liquid Plain had 19th-century settings, and also in the works are a play by Tanya Barfield about Woodrow Wilson, a history of American pop music from composer Michael Friedman, and Rhianna Yazzie’s play about a close confidant of Pocahontas.

This season’s AmRev play, Lynn Nottage’s gritty class drama Sweat, pushes the recent-history envelope as far as ever, with its research-based look at what Nottage has called the nation’s “deindustrial revolution,” particularly in the wake of free-trade agreements like NAFTA. Her play is set in 2000 and 2008 in Reading, Pa., among workers at a local plant whose jobs, and lives, head south in the interim.

Nottage and director Kate Whoriskey spent nearly two months in Ashland working on Sweat—a time commitment necessitated by the unique demands of the repertory schedule, which limits actors’ rehearsal time, even up through tech and previews, but mitigated somewhat by the idyllic Ashland setting. It was not uncommon for Nottage and Whoriskey to get their actors for five hours one day, then have a two-day break before they saw them again. On the positive side, that downtime did give them time to mull their new play.

“It was kind of wonderful to step outside of the rehearsal room into nature, to release the heaviness of the characters we were conjuring in the room,” said Nottage. Added Whoriskey, “The work can deepen in a way that it doesn’t when you’re doing six days a week. That’s a major positive—more time to adjust your thinking.”

Jeff Whitty—whose Head Over Heels, a loose adaptation of Sir Philip Sidney’s Arcadia into a musical featuring songs by the Go-Go’s, is playing this year on the outdoor Elizabethan stage—concurred.

“It’s hard, but it’s also a gift that you have sometimes a couple of days between rehearsals,” said Whitty. “It gave me time to redraft the work, as opposed to rushing changes into the script by the next day.”

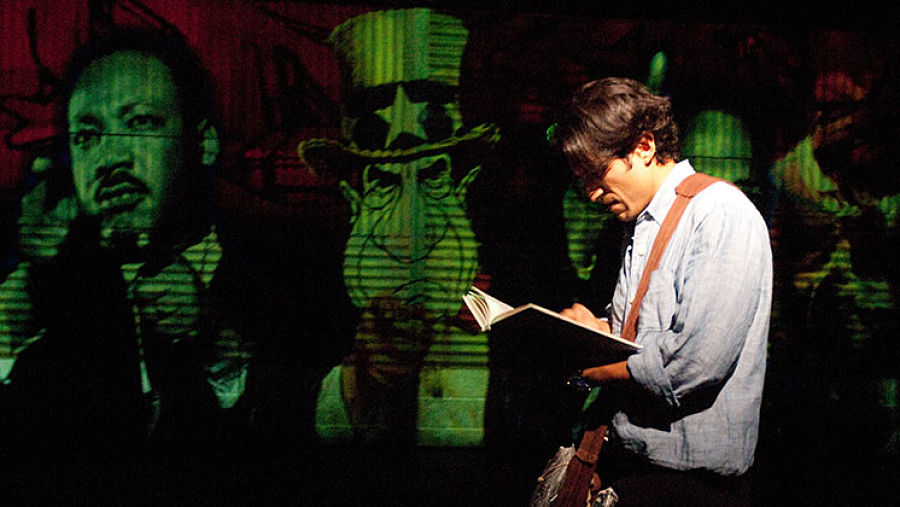

in 2015. (Photo by Jenny Graham)

On the other hand, shows rehearsed this way never build the rolling, all-stops-out momentum toward opening that most theatremakers are used to. And then there’s the matter of previews. All of the new-works artists I spoke with agreed that the preview period at OSF, typically only 3 or 4 performances, is terrifyingly foreshortened compared to the weeks-long process they’re used to. While the New York Times’s Charles Isherwood alighted in August and gave both shows positive reviews, especially Nottage’s (“scorching…extraordinarily moving”), both writers hope that OSF will reexamine this practice.

“They need to look into this preview period,” said Nottage. “For those of us who are used to developing new work, we get a sense of how a play lives and breathes in previews. That’s when Tony Kushner added the Angel’s speech! It’s a real place of discovery. I feel very vulnerable putting work up and getting reviewed after only 3 performances.”

Whitty was more succinct: “Avenue Q had 30 previews before we were reviewed; if it had had 3 previews, you’d never have heard of it.”

Of course, it’s not as if OSF has perversely concocted constraints to impose on its resident and visiting artists. The challenges and conflicts are built into the company’s DNA, even as Rauch and his associates attempt to coil new strands into it. Rotating repertory, like the sonnet form, is one of those self-imposed artistic straitjackets that can paradoxically unleash creativity, even brilliance. Audiences who come to town to see several shows, as do most of OSF’s patrons, know very well the pleasure of, as director Mary Zimmerman puts it, “seeing an actor play King Lear in one show and then the pizza delivery man in another.” Actors, for their part, can blossom over several seasons into versatile, and steadily employed, powerhouse performers.

But OSF is one of just a handful of theatres in North America that still do rotating rep as a matter of course, and the only one, aside from Stratford Ontario, doing it on such a large scale. It’s rare for good reason. The math by itself suggests the headaches involved: Take 100–110 actors, most of them double-cast, and mix and match them into as many as 10 simultaneously running shows on 3 stages, with sets that must be changed out after every performance. Add in workshops, talkbacks, tours, and other special events, and there’s the potential for giant collisions—often literal ones—at every turn. “If you change one thing by 15 minutes, everything has to change,” said executive director Cynthia Rider.

“For a machine that was built to do repertory theatre and do it really well, the wedge of new work—and the size of the wedge of new work we’ve tried to put into the machine—has caused it to pause and stretch,” conceded Christopher Acebo, a scenic and costume designer, and another former Cornerstoner whom Rauch brought on with him as associate artistic director. “We’re still in the space of trying to figure out what we need to adjust.” He acknowledged the new-play-preview conundrum, but added, “There’s hardly a play anywhere, even with 30 previews, that a writer feels it’s done in the first production.”

The process has been particularly rocky with new musicals. Family Album, a new musical by Stew and Heidi Rodewald that premiered in a specially tailored slot last summer, had a notoriously troubled rehearsal process. Recalled director Joanna Settle, “The organization was not equipped to do what we did. This 20-hours-a-week rehearsal thing is a big problem. The cast is screwed if you get rewrites, and there are only rewrites in new work. It was intense.”

And though Whitty called Head Over Heels “by far the most fulfilling experience I’ve ever had doing a show,” the high stakes of staging a new musical on the Elizabethan stage cost the show its original director, Ed Sylvanus Iskandar, who was dismissed a few weeks before opening. Rauch, though busy with Antony and Cleopatra, took the reins.

“The theatre isn’t set up to develop new work, from a lot of different perspectives,” Carey admitted. “Our job is to kind of help hold the new-play baby up when it’s going through this giant machine that is the Oregon Shakespeare Festival.” Added Acebo, “You do have to create a larger pathway for a musical to go through, because there are just more bodies involved in terms of their expertise.”

Dehnert—though she hasn’t yet worked on a new musical at OSF—has done her part to to demystify the process.

“I remember Bill calling me early on for a friendly ear to chat with, because as an organization they didn’t have any built-in knowledge about how musicals get put together,” said Dehnert, who often does double duty as music director for her productions. “They are rehearsable like plays. It’s not that different; your performers just have a different skill set. And it’s good if it’s good, it’s cheesy if it’s cheesy.”

She’s noticed that some OSF company members have set out expressly to develop their singing voices, while Rauch and his casting department increasingly seek out triple threats to join the company. And it’s not like these talents are mutually exclusive with the rep’s main requirements; as Dehnert put it, “The best musical-theatre actors are great verse actors; it’s kind of the same gig.” Added Zimmerman, “Theatre is the noun, musical is the modifier. Especially with old-timey musicals, where there are a lot of book scenes, people will usually accept the second- or third-best voice if it’s the first-best actor.”

Indeed, audiences seem to be lapping up the new dishes along with the familiar staples; sales are as strong as ever. As Rauch noted, “Often the new plays play at a higher percent of capacity at the box office than a given Shakespeare title. So the kind of old model of, ‘New work is risky and Shakespeare is safe,’ doesn’t really hold, you know?”

Rauch noted a trend that might seem counterintuitive at first.

“I’ve had people say, ‘Oh, you want to do those new plays to attract new audiences—we understand,’” said Rauch. “In fact, the most loyal, the most often returning and highest donors are the heart of the audiences for the new work. They take the bigger risks.” For new audiences, on the other hand, the classics are still the most obvious entry point. “You go to a steakhouse, you order a steak,” said Rauch. “So you come to Oregon Shakespeare Festival for the first time, you see a Shakespeare play in the outdoor theatre.”

Executive director Rider also sees the festival’s new-work initiatives as a way to keep the experience fresh for loyal audiences. “Bill is always looking, as many of us are, for, Where’s the stretch that we can do? How do we surprise an audience that has been coming in a delightful way, rather than, ‘Oh, I liked the way it was before’?”

Keeping it fresh isn’t just a matter of aesthetic optimization, though. It’s closer to an ethical imperative: Rauch believes in constantly mixing and remixing the company’s diverse personnel both as an end in itself and as a means to create the most exciting work possible. That approach can lead to fireworks offstage nearly as often as it can produce brilliance onstage, but Rauch isn’t interested in the easy way.

“He’s challenging himself and all of us with the diversity and inclusion stuff,” said Luis Alfaro, the festival’s first resident playwright, whose Breakfast, Lunch, and Dinner was part of Rauch’s first season at OSF. “It can be hard and emotional and combative when on every level we’re trying to challenge the way the company does the work. I’ve been witness to some pretty hard, disastrous moments, and also to some beautiful collaborations.”

Indeed, the many valences of diversity at play—age, experience, ethnicity, aesthetics—aren’t random but integral, and interwoven. Said Alfaro, “The development of a new play is also the development of a new audience.”

As longtime collaborator and sometime OSF director Tracy Young sees it, Rauch’s determination has a purpose beyond merely asking a lot of his collaborators.

“He’s always pushing the spaces to the limits of what they’re capable of, pushing the staff, pushing the art, pushing the boundaries of everything according to his strong passion about what he thinks the medium is capable of offering to the community, the impact he sees it can have,” said Young, whose festival work has included A Wrinkle in Time and a long-brewing collaboration with Rauch, Medea/Macbeth/Cinderella. “He manages to somehow enhance everything—the tradition, the legacy, but also the pushing forward.”

Lue Douthit, the festival’s director of literary development and dramaturgy, whose tenure predates Rauch’s, put it this way: “We all get to have a new day every day. It can be challenging, and I think even he would say, ‘Oh my God, can we do something the same way twice?’ Then I think, Well, that’s not how work happens. Right? It’s not easy, what we do. It’s actually kind of hard. I think we just want to stretch every way we can—not every way all the time, but every way we can.”

Said Dan Donohue, a ginger-haired 12-season veteran who played Hamlet under Rauch and Henry V for Appel, “The thing I know about Bill—the thing that inhabits every fiber of his being—is that he’s somebody who’s constantly examining and reexamining how to give the people he’s working with a voice. He wouldn’t be in the theatre at all if he didn’t feel like he had a way to give that to those who might not have had that chance.”

Dehnert said that Rauch’s risk-taking is what makes her eager to come back. “I think it was Peter Brook who said, Directing is a lot like getting everyone into your boat, and you’re not even sure that’s the right way, but you tell them where to go. And things are going to happen along the way. Bill is willing to do his job.”

For his part, it was in describing the thinking behind his hiring so many first-time directors at OSF that Rauch may have offered the most honest mission statement, and self-review, of his eight years at the festival’s helm so far, straightforwardly addressing the many contradictions bundled into a worldview oriented more to “and” than “or.”

“It’s really hard on the company, and really hard on the production staff,” he admitted. “I think it’s both thrilling and challenging for the acting company and the audience. The schedule of rotating rep is so unforgiving, but I still believe in it. And I still believe in the artistic vibrancy that comes from bringing in a lot of new perspectives.”

Or, as Shakespeare scholar Russ McDonald wrote, “Romance arrives at a happy ending by an unusually perilous route.”