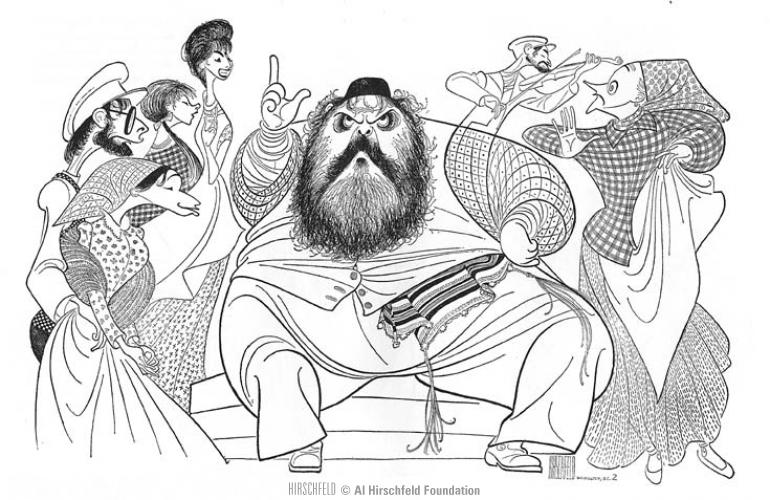

NEW YORK CITY: The words “caricature” and “Al Hirschfeld” might as well be synonyms. The late artist, who died in 2003, built his eight-decade-long career composing iconic drawings of Broadway productions and the stars within them. From Ethel Merman to Billy Crudup, from the Marx Bros. and Whoopi Goldberg, nearly anyone who strutted on Broadway has been Hirschfelded.

A new exhibition at the New York Historical Society, “The Hirschfeld Century” (through Oct. 12), and a new book, The Art of Al Hirschfeld, by exhibition curator and longtime Hirschfeld archivist David Leopold, puts the focus where the artist did: on the stage. The exhibit contains 100 original drawings, and includes many pieces on display for the first time. It chronicles Hirschfeld’s career from beginning to end (including a seven-decade stint at the New York Times), making it the most comprehensive collection of Hirschfeld’s work to date.

In creating the exhibition, Leopold strove to show how Hirschfeld’s work accurately depicted the changing times over his long career, while at the same time creating drawings that transcend their period. According to Leopold, each work included in the book and the exhibition is an example of how Hirschfeld was effortlessly able to record a moment in time and make it appear timeless.

“It not only helped define what was happening, but recorded what was happening,” Leopold said. “He helped define iconic figures like Oliver Hardy and the Marx Bros. Genius was a dirty word in his house, but that’s exactly what it was.”

Hirschfeld created his signature style after a trip to Bali in the ’30s, where he noticed how the almost-blinding sunlight bleached out all color, leaving behind only black and white lines. When broken down, that described Hirschfeld’s drawings to a tee: simple yet elegant arrays of black and white lines.

“Al can make things move in one drawing that takes animators 24 frames to do,” Leopold said. “A lot of animators today—like Brad Bird, Pete Doctor and Eric Goldberg—will tell you what they’re trying to do is what Hirschfeld did. When they’re creating a character, they want that drawing they do to sum it all up.”

As simple as Hirschfeld’s work appears at first glance, it contains many layers. For one, there’s the pastime of counting “Ninas”—the number of times his daughter’s name appeared in one of his Sunday New York Times pictures. Admirers also liked to point out how Hirschfeld’s depiction of people was so scarily accurate that the subjects began to resemble their portraits, instead of the other way around.

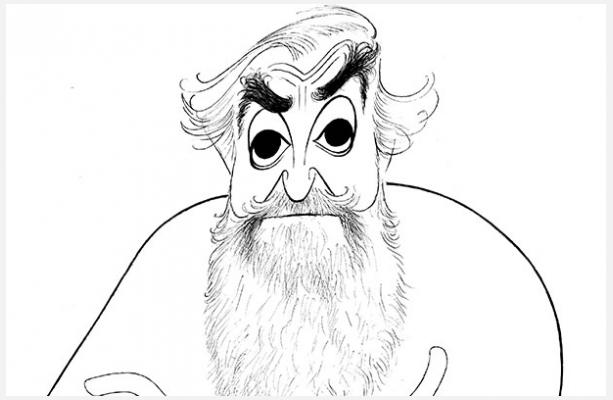

Al Hirschfeld Self-Portrait, 1985. Ink on board. Melvin R. Seiden Collection of Drawings by Al Hirschfeld, Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University. © The Al Hirschfeld Foundation

Hirschfeld developed his knack for summing up scenes and personalities with minimal visuals by working live, primarily at rehearsals or at opening night performances, with his sketch pad typically tucked halfway into his pocket so that no one else could see his work in progress. With just a series of pen-and-ink lines, Hirschfeld was able to capture dance movements or gestures of the actors on the page.

As time progressed, Hirschfeld became the most requested artist on Broadway, attending nearly every single opening night for 70 years. Despite the accolades, he never lost sight of what his fame was based on.

“It was about these people, it was about the drawing he was going to do,” said Leopold. “He was interested in what was happening now. And he recorded it, he interpreted it. And because he was a visual journalist with a distinct point of view, he had a different way of seeing.

“What he was going for was a drawing that stood the test of time, while what editors were going for was a drawing that was of its time,” Leopold continued. “For a performer, it was, ‘I got my time with Hirschfeld.’ His work served all those functions.” With the gift of hindsight, though, it seems that the artist’s goal has been met. “Now, I think we’re really finding out whether his drawings stood the test of time,” said Leopold. “As biased as I am, I think they do.”