NEW YORK CITY: Songwriter/performer Stew, best known for his 2008 Tony winner Passing Strange, is not afraid to make audiences uncomfortable.

“I want to mess with the things that people don’t mess with and talk about the things that people don’t talk about,” he says. His new project Notes of a Native Song, which will have a short run June 3-7 at Harlem Stage, is his latest provocation. Inspired by the work of the playwright, novelist and essayist James Baldwin, who’s exerted a huge influence on Stew over the years, Stew’s show refers to Baldwin’s seminal essay collection, Notes of a Native Son, itself a reference to Richard Wright’s legendary novel of black struggle, Native Son. Stew is quick to point out, though, that none of Baldwin’s actual words appear in the script.

“I’m making a show about what he did to me as an artist,” he says. “But the words and the songs are mine.”

Baldwin first got onto Stew’s radar when he was in elementary school in California in the early 1970s. Though he was too young to actually read the author’s dense and demanding prose, Stew was fascinated when a teacher mentioned that Baldwin was among a few famous black artists who had left America for places where they would feel freer to do their work. (In Baldwin’s case, it was France.) These tales of flight were, Stew says, “stories of possibility.” When he finally read Baldwin’s first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain, in high school, he was hooked: “He has this ability to get under your skin and into your brain.” Ever since then, he has seen Baldwin everywhere. “He always manages to show up,” he says. “He’s like Shakespeare.”

Notes of a Native Song is one of the culminating events in the Year of James Baldwin, a 14-month cultural festival marking the 90th anniversary of Baldwin’s birth, cohosted by several venerable New York institutions, including New York Live Arts, Columbia University and Harlem Stage. Stew was at work on a show about life in Harlem when Patricia Cruz, the director of Harlem Stage, approached him about doing a Baldwin piece for the festival instead. He couldn’t resist.

Lest we get too cozy, though, Stew reminds us that this is “not a sweet little tribute” to Baldwin. “Because black people have been so put upon, our heroes have to be sanitized, have to be perfect. I want to delve into the parts of Baldwin that the mainstream intelligentsia doesn’t talk about. I want to explore his dark sides.”

Stew especially wants to avoid the kinds of overly simplistic readings of Baldwin he’s seen popping up in the press lately in connection with reports of police brutality and rioting in Baltimore and elsewhere. While Baldwin’s eloquent and brutally honest words about race seem to resonate in these charged times, Stew is concerned that people are missing his real message.

“Baldwin was constantly telling us that the situation in America is much more complicated than you think it is,” he says. “You can’t make yourself feel better by just seeing it. You have to ask yourself how you are complicit in it.”

This is far from Stew’s first time wading into the shark-infested waters of race in America. He has been the frontman of a band called The Negro Problem since the early ’90s and has been writing songs and making shows about the black experience (among other things) ever since.

His greatest recognition came in the form of his Tony Award for his book for the musical Passing Strange, a semi-autobiographical rock show about a young African-American man who takes a long journey from home in order to find his way back again. The main character, Youth, lives abroad in Europe for several years, like Stew and Baldwin before him. In fact, Baldwin’s touch was all over that show, too, but Stew didn’t realize it at the time.

“I reread Go Tell it on the Mountain after I did Passing Strange, and there was so much Passing Strange in that novel, it was like I had committed spiritual copyright infringement,” Stew says.

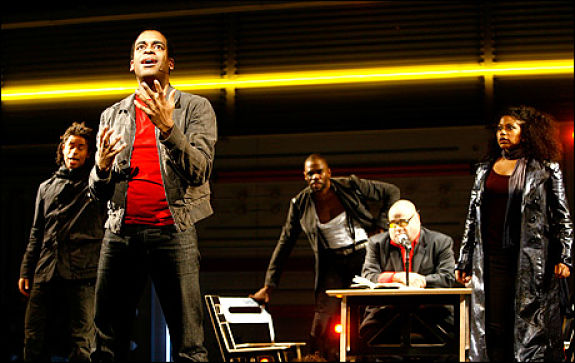

Like Passing Strange, Notes of a Native Song will be more of a story, or series of stories, with music than a “musical” per se. Stew is once again working with his longtime writing partner (and one-time girlfriend) Heidi Rodewald, also a member of The Negro Problem. Heidi describes the Baldwin show as more of a “song cycle” than a play. Stew agrees: “We use the concert form as our way of making theatre. We play songs, and there’s banter among the band, but the banter is semi-scripted and thematic. There’s a narrative.”

Since they generally “create the show right up until showtime,” according to Stew, the actual structure of Notes of a Native Song remains nebulous, but he thinks it will probably end up looking like “a concert in chapters. Our little concert novel,” he laughs.

Why do Heidi and Stew keep making art together, even after the wrenching breakup that generated the songs on the band’s 2012 album Making It? And why does it still work?

“We have this long, long history with each other,” says Heidi, “and we’ve spent a lot of time in cars together!” Stew remarks that they grew up in the same part of the country at the same time and listened to the same bands. “There’s a shorthand,” he says. “We both grew up listening to R&B and punk. She knows both and understands how they’re connected. We share an aesthetic. That’s hard to come by.”

For Notes of a Native Song, as for Passing Strange, they compose the music together and Stew provides the book and lyrics. It’s a symbiotic partnership that has allowed them to keep generating their own unique brand of musical theatre.

Occasionally they do go their separate artistic ways (although Stew reportedly wouldn’t let Heidi off the hook when she initially tried to get out of working on the breakup album). Recently, alongside work on the Baldwin project, Heidi wrote the music for Another Kind of Love, a musical by Brooklyn-based playwright Crystal Skillman, now playing at Chicago’s InFusion Theatre Company. The story follows an all-sister punk band that reunites for a concert to commemorate their mother’s suicide. “Crystal is amazing,” says Heidi, “and I got to play loud, distorted guitars, which made me happy.”

But these days Stew and Heidi are both deeply immersed in Baldwin, and they’re both hoping the piece will have a life beyond the festival. They also, as usual, have some other projects up their sleeves. The Total Bent, a show exploring the fraught relationship between fathers and sons, was slated for last season at the Public but got pushed to spring 2016 because the director, Joanna Settle, found out she had breast cancer just before rehearsals were supposed to start. Settle is now (happily) cancer-free, and Stew and Heidi are set to resume work on The Total Bent, but not before they mount a mash-up of Wagner’s operas at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. in September. (Last summer they premiered a new musical, Family Album, at Oregon Shakespeare Festival, directed by Settle.)

The father-son theme of The Total Bent looks like another nod to Baldwin, whose own father loomed large and troubled in both his life and his fiction. Did Stew have Baldwin in mind? “Originally I thought, because Passing Strange was a play about a mother and son, now we should do one about a father and son. So, no, not consciously,” he muses. “But definitely subconsciously. Like all my good ideas, James Baldwin had it first.”