While watching Hamilton, the universally praised new musical from Lin-Manuel Miranda, I found myself taken with a simple thought. The liveliness and intelligence of Miranda’s writing had done much to make revolutionary America feel vivid and present for an audience jaded 21st century New Yorkers, most of whom can barely contemplate life without their smartphones, let alone life in 1776. Yet so did his (and his director’s) deceptively simple decision to assign most of the show’s major roles to Latino, black and Asian actors.

When I was born, at the very end of 1979, 80 percent of the U.S. population was white. Today, that share has fallen to 63 percent, and it’s expected to fall still further in the decades to come. Among children under 18, whites represent roughly half of the population, and the white share keeps shrinking as you look at younger and younger kids. Granted, it’s a bit silly to speak of white people as though whiteness were a coherent or consistent category. To be white is to be a part of a diffuse population that’s always expanding at the edges. Decades from now, it’s possible that tens of millions of people with a Fujianese or a Colombian grandparent, or both, will happily identify as white, and we’ll think nothing of it. If this does happen, and it’s very easy to believe that it will, perhaps America will never become a majority-minority country, as the white majority will slowly, steadily be redefined.

What I can say, however, is that as an elementary school student learning about America’s founding generation—the desperate fight for independence, the roiling controversies over the basic structure of the American republic—I didn’t see myself in the story. I think I understood that these men were important, and even that they were daring, brilliant and inventive. Perhaps I was even grateful for their accomplishments, though I don’t want to give my younger self too much credit for thoughtfulness. I was certainly rooting for the revolutionaries, if only because I don’t recall having learned all that much about the virtues of the Loyalist cause. But I never developed an emotional connection to Alexander Hamilton or George Washington. These were austere and remote figures, who just happened to be whiter than white.

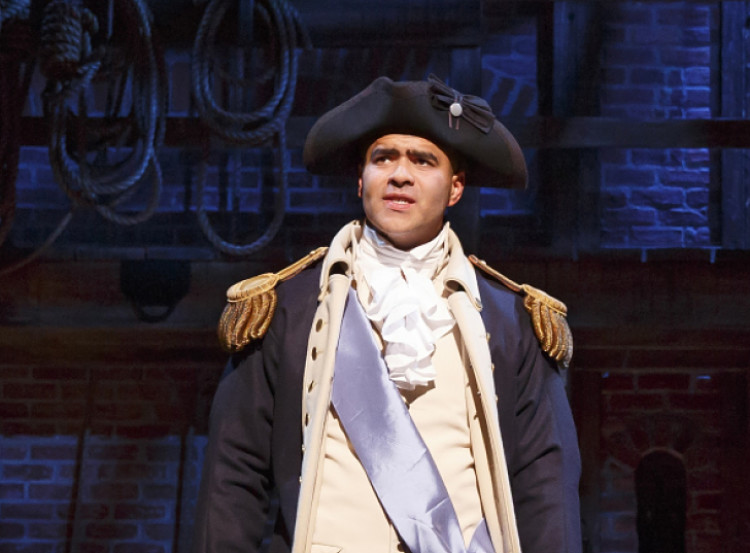

So I was struck by how effective it was to see the likes of Hamilton and Washington portrayed by people who looked like me, or if not like me than like many of my classmates and lifelong friends, and to hear them express themselves through rap, the lingua franca of my youth. By casting non-white actors, the production sharpens the sense that Hamilton and his associates were, like many upwardly mobile women and men of our own time, code-switchers. They were Englishmen who demanded that their rights as Englishmen be respected. Yet they were also Americans, who keenly felt their second-class status as the country cousins of their English rulers. Eventually, this divided identity gave rise to a hybrid one—an experience not unfamiliar to first- and second-generation Americans today. Seeing George Washington with a non-white face helped me register exactly why he was so magnetic and compelling to his contemporaries. Seeing Alexander Hamilton as a wispy Dominican rapper, similarly, helped me fully appreciate the fierceness of his intellect.

Leaving aside the considerable merits of Hamilton as theatre, Miranda’s production offers a roadmap for how to keep our national mythologies alive. There’s a widely held belief that America is more of an ideological project than a nation in the traditional sense, built on shared ancestry and shared memory. I tend to disagree. We are a nation with a culture, albeit a loose, inclusive and highly adaptable one. And as a nation, we need stories about where we come from and why our culture has taken its distinctive shape.

Those of us who grew up in America’s sprawling metropolises might not fully appreciate that there was once a vigorous debate over whether America should become an industrial powerhouse, and whether the young republic should embrace financial engineering as a source of strength or reject it as a corrupting temptation. Hamilton was the partisan of a less innocent, less democratic, more urban, and more dynamic nation, and that’s the path we eventually chose. Our America is recognizably Hamilton’s, when seen through the right lens.

My guess is that the America of the future will still be Hamilton’s America, though it will be far more Latin than WASP. Miranda and his brilliant cast deserve enormous credit for bringing that to light.

Reihan Salam is the executive editor of National Review.