A waitress delivers your salad, flirts brazenly with your date, and a few minutes later dangles several feet above your table from a trapeze.

You are handed a printed benediction, and urged to recite it in honor of the free-range roast chicken you are about to eat. Her name was Henrietta.

A flamboyant chef quits, and taps you to audition for his job—in front of several hundred fellow diners. The audition involves dance moves and a soupçon of public humiliation.

There is dinner theatre, and then there are dinner theatrics. In Seattle, two stage companies—Café Nordo and Teatro ZinZanni—have devised deliciously idiosyncratic forms of the latter. In this cuisine-conscious, theatre-rich city, both troupes are whipping up moveable feasts for hungry audience—and redefining a genre.

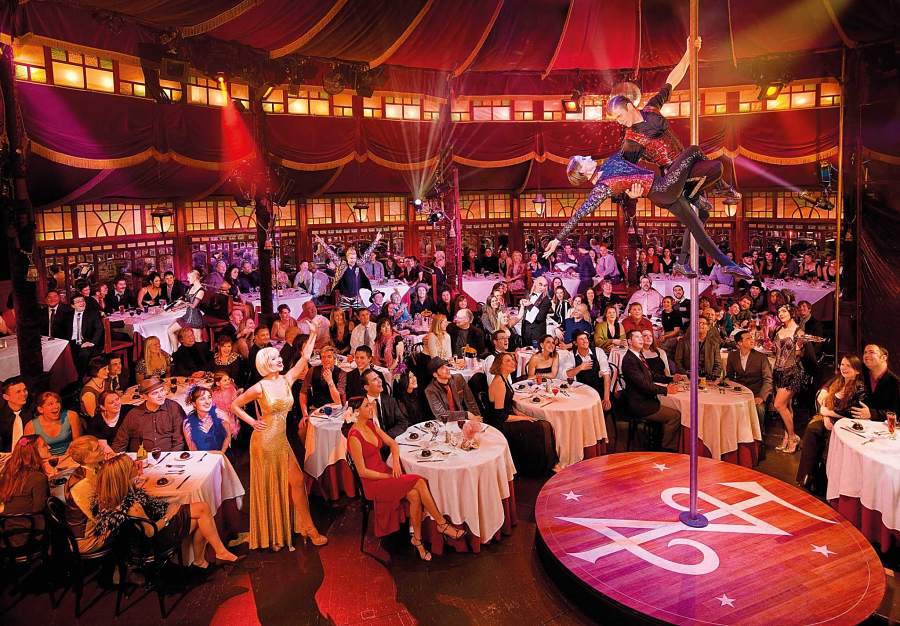

Since 1999, Teatro ZinZanni has grown a loyal following by blending modern cuisine and fables garnished with European-style cirque display and audience interaction. In an antique Belgian Spiegeltent near the civic cultural hub known as the Seattle Center, the company’s creed is to present “Love, Chaos and Dinner” in several new productions a year. On the menu: live music, circus stunts, G-rated bawdiness and some of the sharpest comedy improvisation this side of the Rockies, folded into a five-course meal.

For six years Café Nordo has been whipping up its own blue-plate special, staging creatively dramatized meals spiced with eco-awareness, pop-cultural satire and tipsy music. And the formerly footloose troupe has just found a new home in the historic Pioneer Square district that will serve as a test kitchen for the many possibilities of, well, playing with food.

Serving up a show with vittles must hark back to our Cro-Magnon ancestors, who danced and told tales around the cave fire while tearing into haunches of barbecued rabbit and reindeer. Later there were Roman entertainment feasts, Middle Ages madrigal banquets—and, eventually, in mid-20th-century America, dinner theatres that sprouted up in cities and towns across the U.S.

At their best, the latter brought Hollywood stars to the hinterlands in solid professional productions. At their worst, the musical revivals and comedy chestnuts on offer were as bland as the fruited Jell-O molds and rubbery chicken that accompanied them.

There are still commercial dinner theatres around, including quite a few in the whodunit, mystery-mansion mode. But fresher spins on staged cuisine for a new generation have also emerged—pop-up performances held in homes or other intimate spaces, or in more elaborate, lingering formats, like the recent Off-Broadway musical wonder Natasha, Pierre and the Great Comet of 1812 (inspired by segments of Tolstoy’s War and Peace and featuring a full Russian dinner), or the opulently decadent Queen of the Night bacchanal that held forth for over a year in Manhattan’s fabled Diamond Horseshoe ballroom.

What makes Teatro ZinZanni and Café Nordo distinctive? Their staying power. And their continuing exploration of an expandable artistic (and culinary) identity, sauced with Northwest whimsy.

Café Nordo is the brainchild of theatre director and food maven Erin Brindley and writer-producer Terry Podgorski. The two met working behind the scenes with Circus Contraption, an avant-garde Seattle collective with a sleazy steampunk aesthetic Podgorski describes as “Tim Burton meets Cirque du Soleil meets Tom Waits.” Surreal, R-rated and transgressive, the punk-burlesque cirque swung to a ragged gypsy/jazz beat, and won over audiences on the West Coast and in Off-Broadway runs at Theatre for the New City.

When the troupe split up in 2009 over artistic and other differences, Podgorski dusted off a short story he’d written about a maniacal chef who told stories through his dinners. With Brindley and some Contraption alums, he created an imaginary cult around a mysterious chef named Nordo Lefesczki, and the first Chef Nordo event took shape.

With a shoestring budget and no on-site kitchen (everything had to be prepared and trucked in from an outside facility), the team turned the rustic Theo Chocolate Factory warehouse into a shabby-chic supper club presenting The Modern American Chicken. The show melded an exquisite, witty, multi-course dinner (designed by Brindley) with an antic/serious paean to a righteous hen who sacrificed her brief life for the audience’s gustatory pleasure.

The performers were also the waitstaff. There was original choral and instrumental music by the marvelous Circus Contraption musician-composer Anastasia Workman. Chef Nordo’s metaphysical theories about food were generously quoted, though he never appeared. And in between the shot of parsleyed chicken broth and the divine panna cotta, one learned plenty, through song and story, about the lifespan of a well-tended, organic chicken.

After selling out the run to curious foodies and game theatre patrons, Café Nordo popped up again at Theo Chocolate in 2010. Their second show, Bounty!: An Epic Adventure in Seafood, had a more environmentalist slant. Sea chanteys, monologues about sustainable aquaculture and a sprinkling of zombie antics peppered a meal one experienced with strangers who became dinner companions at communal tables. Each party had to “go fishing” on tabletops for a variety of shellfish from Northwest waters, stocked in glass aquariums. Then teapots of fragrant Alaskan halibut broth were passed around to soup up what was netted.

Since then, Café Nordo has frequently reinvented itself with new themes and pop-cultural contexts. One show mused about the historical passions and perils of liquor, via a hard-boiled detective tale. A “Twin Peaks”–inspired evening reflected on the environmental desecration of the American West, and served up a clever breakfast of mashed potato “donuts,” dunkable in “coffee” gravy.

A mock-trip to the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair was cast as a spy thriller set on a jumbo jet that served passenger/patrons a history of the Green Revolution and the airplane food of one’s dreams.

“One of the things that keeps the Café Nordo concept fresh for me as an artist is figuring out new ways to connect the food with the show,” says Brindley. It’s not difficult, she adds, because “food connects us to each other, and it’s a portal to economics, politics, sociology, nutrition. It’s also about community—about storytelling and mythology.”

Café Nordo has also had its arty, site-specific excursions. In Chef Nordo’s Cabinet of Curiosities, inspired by early Expressionist cinema and musty museums, the audience was led around an old lodge building to take in surreal scenes in trippy scenic installations. A Fellini-esque dinner came at the end, around a giant table in a former ballroom.

Though Café Nordo works a gimmick, it’s a sustainable one. The scripts by Podgorski are not always up to the concepts. But there are always quirky surprises from the eccentric roving players, and the delectable food is rhetorical without being didactic.

After shuttling between several kitchen-less venues around Seattle, Café Nordo finally has a permanent base. On a $300,000 renovation budget culled from individual, civic and crowd-funded donations, over the past year the company transformed a storefront, formerly Elliott Bay Books, in Pioneer Square’s historic Globe Building into the Culinarium, a flexible performing and dining space with a kitchen in the basement below.

Podgorski and Brindley are already envisioning a groaning board of future activities—acting and cooking classes for disadvantaged kids, culinary exhibits, a food/film series. And they’re working on collaborative possibilities with groups like the food-and-justice activist organization FEEST (Food Empowerment Education Sustainability Team). “We want Café Nordo to be a Seattle institution that expands on our initial model,” according to Podgorski. “I’d love to take over a space on the waterfront and run a show about the history of Seattle through food. I also want to see what creations come out of pairing a visual artist or a poet with a chef.”

Across town at the gilded Teatro ZinZanni cabaret tent, the mission is simpler and appetizing on its own terms. The popular institution dates back to 1998, when Norman Langill, then the director of the nonprofit festival production company One Reel, wanted to return to his roots as the founder-maestro of the funky, long-defunct One Reel Vaudeville Show touring outfit —but this time, with a Moulin Rouge–like setting evoking the retro-glamour of old school European cabaret.

Langill firmly believed that the boom in couch-surfing, home-theatre, digitized entertainment (much of it emerging from the Seattle tech sector) would also produce a counter-longing for excitingly live, communal and in-your-face diversions. “The idea was that people could sit down together, share a meal, talk with each other and at the same time enjoy some of the best performers around,” he explains.

A century-old Spiegeltent, outfitted with stained glass, mahogany paneling and velvet-seated booths and leased from its Belgian owners, seemed the perfect environment for the elegant yet zany (and relatively affordable) evening out he had in mind. His One Reel compatriot Louise DiLenge would design the belle époque-style décor, graphics and eye-popping costumes. Composer Norman Durkee would orchestrate live scores of big-band jazz, rock and carny music, for singers and social dancing. Top Seattle restaurateur Tom Douglas would come up with the multi-course menu, cooked on-site.

Most important, Langill recruited creme-de-la-crème-skill acts (acrobats, jugglers, contortionists) from Cirque du Soleil and other New Wave circuses around the globe. He also enlisted glam singers, from blues belters and opera divas to Gaga-esque New York cabaret chanteuse Lady Rizzo, as well as adroit clowns to keep the plot bubbling while serving and disturbing the diners.

The formula thrived in Seattle, despite several changes of downtown location. And Langill has since exported it briefly to a Southern California site in Costa Mesa, and more prominently to a San Francisco pier, where that branch of Teatro ZinZanni ran for 11 years. (He is currently a planning a new waterfront site in San Francisco, where the Spiegeltent would be encased in the glass gazebo of a hotel complex.)

Langill conceives all ZinZanni productions and directs many of them. And he changes up the dinner-cabaret gambit, and draws repeating patrons, by altering the mood with homages to different showbiz eras and social milieus. There’s been a sensuous tribute to la vie en rose of the Folies Bergère, starring Tony-winning singer-actress Liliane Montevecchi and directed by Tommy Tune. In the politically spiked Caliente!, the cast played Latino kitchen workers protesting layoffs caused by gentrification. (It was staged by Culture Clash member Ricardo Salinas.)

The company has also branched out into late-night, adults-only cabaret offerings. And it attracts families with weekend afternoon shows designed for children (hot dogs and popcorn served) as well as classes and a summer camp that teaches young people circus skills—“to help keep the traditions alive,” says Langill.

But the key ingredients of the franchise are the derring-do and outrageous comic hijinks in the roving repertory company Langill has assembled over the years. “It’s interesting because the circus people get a chance to create characters in our shows,” he notes, “and the theatre-trained actors get to do a lot of improvisational comedy.”

Two prime examples are comic performer Frank Ferrante, who has headlined ZinZanni shows for 15 years, and aerial artist Dreya Weber, who recently appeared in her fifth show with the Seattle company, The Hot Spot.

“My career path was always compartmentalized,” reports Weber. “In New York I worked in theatre, but discovered I could make a better living doing aerial acts. Doing aerial choreography [for Pink, Madonna and Cher] in pop-music shows was another creative challenge with different parameters. But the best thing about Teatro ZinZanni is an opportunity to use all these different disciplines in one place.”

Weber recently has evolved a transformative character who draws oohs and aahs when she morphs from a sharp-witted, hobbling crone swathed in dark lace into a high-flying bird draped over a silken swing.

Ferrante, who alternates tours of his solo show An Evening with Groucho Marx with ZinZanni gigs, is one of the comic linchpins Langill relies on—along with such neo-vaudevillian merry pranksters as Geoff Hoyle, Kevin Kent and Christine Deaver.

Playing the raucous, lecherous Chef Caesar, Ferrante announces the dinner courses with bellowing gusto, and craftily recruits volunteers for outrageous skits. He’s one of those great quipsters who can win laughs by putting a schlubby suburban guy attending the show with his grandchildren through some off-the-wall comic paces, without inflicting cruelty. “Every night is hugely different, depending on whom I pick,” Ferrante allows. “Every night has different comic challenges.

“The term dinner theatre has such a bad rap,” Ferrante goes on to observe. “My first job was in a dinner theatre, where you were competing with the pumpkin fritters. But I love vaudeville, and it was always my fantasy to come up with a larger-than-life character like W.C. Fields and Groucho had. I’ve been able to do that with Caesar, and I don’t know another show that encourages interaction with the audience as much as this one does.”

And what about the meal? Is it an interruption of his act? A distraction from it? Not for Ferrante. “There’s something elemental about people eating together, something that heightens the experience,” he muses. “There’s a synergy between the dining and the show. When you’re only watching, you’re in a different kind of state.”

Seattle-based critic Misha Berson writes regularly for this magazine.