We must fight for all those who do not!

We must ask for all those who do not!

We must make those who do not listen hear!

We must weep for those who cannot weep!

We must live to sow! Always to sow!

—Sembrando (Sowing), by the Spanish writer Manuel R. Blanco Belmonte

This story is about seeds. It’s about locating the origins of a new wave of international collaborations between companies based in the U.S. and Mexico, and taking an in-depth look into their gestation.

There are many such collaborations happening now—and as they become more plentiful and blossom into long-lasting unions, bonding across the border becomes an ever more essential part of the North American theatre landscape.

The story of these seeds is about regeneration in the darkness—and the flurry of international theatrical collaborations has ingenious parallels to that process. Language and politics may differ across cultures, but one thing remains the same—the seeds planted by theatremakers sprout strong roots that strengthen the collective human fiber. “Theatre transcends languages,” says one such dedicated seed-planter, Carlos Alexis Cruz.

An American performer who teaches voice and movement at the University of North Carolina–Charlotte, Cruz is trained in the circus arts and physical comedy and has performed in Mexico, Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic.

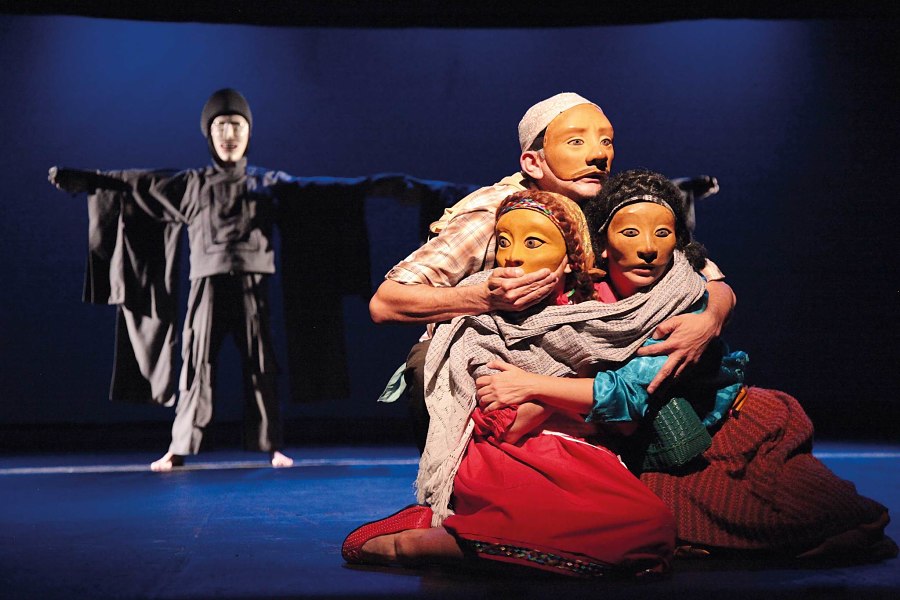

Alicia Martínez Álvarez, a Mexican mask-maker and founder of Laboratorio de la Máscara (or Mask Laboratory), collaborates frequently with Cruz on creating traditionally derived yet groundbreaking models for reviving the ambulant theatre.

“What is important about collaboration is that it enables the American community with Mexican origins to come in touch with their culture, via their histories, roots, myths and artistic manifestations in a variety of forms,” Álvarez explains. “It is the only way we can hope to communicate the complexity of what the Mexican people are living through today. Mexican-American communities have maintained strong and loving ties to their roots, but it is time to actively participate in the collective creation of our united story, in pursuit of a just and honorable Mexico.”

However, collaborations aren’t always easy. “I have to admit, originally, I didn’t want to collaborate with the U.S., because in Mexico, artists are very prejudiced,” suggests another seed-planter, Martín Acosta, a Mexican director who recently worked in Valencia, Calif., with Duende CalArts and Marissa Chibas on a piece tackling immigration topics. “We stick to a certain ideology, and, of course, this can be limiting. Collaborations open up our ability to connect.”

Cruz, Álvarez, Acosta and Chibas are among those who will tell their stories here.

There’s Meaning in Movement

Every year, tens of millions of monarch butterflies abandon the Canadian south and the northeastern borders of the United States to perform a monumental travesía, or journey—a journey that leads them south and into the central highlands of Mexico. Come fall, they mate in their wintering grounds in the mountains of Michoacán, a powderkeg of a state known for incessant warring amongst members of cultish cartels, vigilante citizen “auto-defense” groups and uniformed forces. In local myth, the butterflies are believed to be the souls of the dead returning to Earth.

The butterflies’ migratory destination—a conflict zone of centripetal proportions—is also the home of another type of unquiet movement. Almost 2,000 miles south of the Carolinas, an ambulant theatre troupe named after Miguel de Cervantes’s equine vessel, Teatro Rocinante, brings back the notion of traveling theatre in Michoacán.

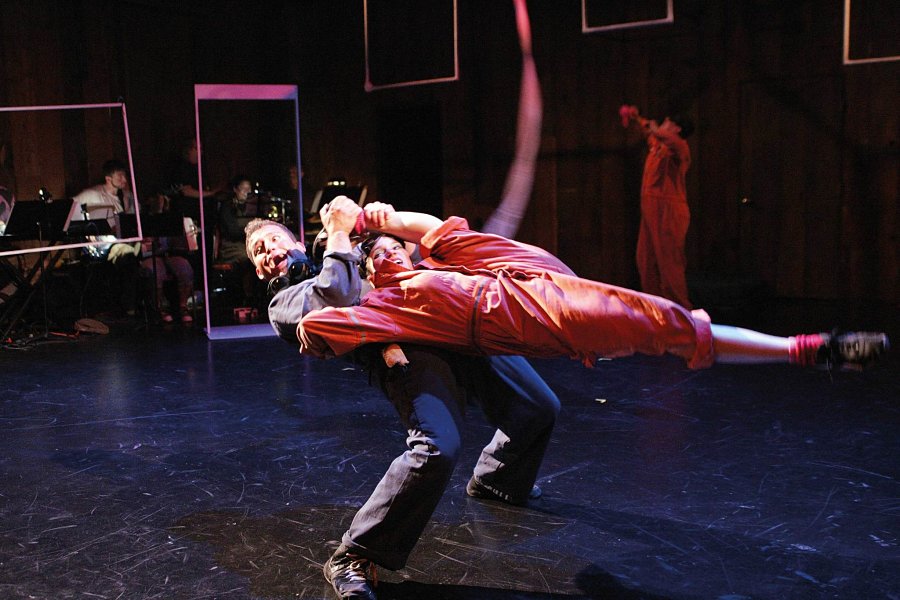

“It has always been a dream of mine to explore the possibility of having a traveling stage, à la Michoacán’s Teatro Rocinante,” says Cruz, who counts among his honors a 2011 Princess Grace Acting Fellowship, the 2014 McColl Award from the Arts & Science Council and, most recently, an On the Road Grant from Theatre Communications Group. Cruz is affiliated with Portland-based Pelú Theatre, a company that fuses urban narratives with hyperphysical storytelling. The theatre recently worked with Miracle Theatre Group, also in Portland, on Lazarillo, a bilingual adaptation of the Spanish novella Lazarillo de Tormes that reimagined the central picaresque character from Inquisition-era Spain as a guy from the Bronx in the ’80s and used elements of hip-hop, circus, acrobatics and commedia dell’arte.

His newest project involves a traveling theatre, which was still in the process of being built at press time. Entitled Pícaro, which means “rascal,” this project will utilize a “Rascal-mobile,” a vessel named Max, as a performative and edifying tool to examine the immigrant experience from different angles.

“I believe it is essential to be able to tell the story of immigration from the in-house point of view, meaning investigating the difference between the ‘Calvary’ journey, as it is known to Mexico immigrants, and the ‘Route of the Beast,’ as it is known to Central Americans,” Cruz explains.

Cruz’s own investigation into the phenomenon of northern migration mimics the journey of the monarchs, who travel north to south. He believes that a moving theatre can switch the gears of the assimilated into the no-longer-assimilating, transform the unheard into the heard. “When you walk a road, you take pieces of that road with you,” he reasons.

Cruz met his Pícaro collaborator Álvarez on a previous journey, at the Dell’Arte International School of Physical Theatre in California, where she was a resident artist. They complement each other. Cruz produces kinetic theatre (think circus meets musical theatre), as seen in his adaptation of A Suicide note from a cockroach in a low-income housing project by Nuyorican poet Pedro Pietri. Álvarez’s specialty is strong narrative mythos told through mask. An example of the latter is El Viaje De Tina (Tina’s Journey) by Mexico playwright Bertha Hiriart, which was the product of a collaboration between Máscara and Cara Mía Theatre Co. of Dallas.

“I am interested in mask as it’s represented in different territories—traditional, anthropological, psychological,” reflects Álvarez, “and fundamentally in how that gives life to characters or a story on stage.”

Together, Cruz and Álvarez will treat the complexities of immigration utilizing their individual techniques and adjusting them to the particular cultures of the places they visit.

“My travels to Mexico City provided me more data on how traveling stages and outdoor theatre is still present and vibrant in all cultures,” Cruz explains. “These moving spaces bring the work directly to the people. You can ask questions, and you can have an effect by means of interpretation and constant creation.” He means often un-asked questions, such as: What do people take with them when they immigrate? What baggage, rituals and traditions do they leave behind when they assimilate?

Cruz’s physical-theatre background favors the transcendence of language barriers, and through the art of mask, Álvarez resuscitates an authentic yet deeply buried use of ritual in Mexican myth and folklore. Like the flight of the monarchs, this collaboration seems to put into action the idea that who we are depends on where we’ve been, as well as on where we are going.

Reconnecting Islands

In the traditional Spanish dance flamenco, “duende” is a common term with an uncommon significance. Its simplest meaning is “goblin, demon or spirit,” but some say it’s the most difficult of all Spanish words to define. In 1933, poet, playwright and director Federico García Lorca delivered a famous lecture on the nature of duende in which he called it “a mysterious force that everyone feels and no philosopher has explained.” Duende, he added, “works on the dancer’s body like wind on sand.”

Nestled on a Valencia, Calif., campus, the CalArts Center of New Performance adopted the term for its six-year-old sibling program, Duende CalArts. Helmed by Marissa Chibas, the theatrical virtuoso and majestic performer behind works like Daughter of a Cuban Revolutionary and the silent-film/live-performance Clara’s Los Angeles, Duende CalArts’ mission is to “bring together prominent national and international Latina/o artists to develop adventurous, multilingual works.” Duende’s inaugural production in 2009 was the world-premiere adaptation of Nobel laureate Octavio Paz’s epic poem Piedra de SolSunstone, directed and translated by Maria Morett of Mexico City.

In 2012, CalArts, in collaboration with the University of Guadalajara, premiered Timboctou, authored by Mexican writer Alejandro Ricaño. Chibas remembers that time as one of plentiful success, particularly on the collaborative front.

“The team of artists really fell in love, even those who literally did not speak the same language,” says Chibas. “They shared the language of creating something together.”

Timboctou merged a team of actors and designers from Guadalajara and other parts of Mexico with the CalArts Center of New Performance, and the production also marked the beginning of Chibas’s artistic collaboration with Acosta. He echoes Chibas on the success of the Timboctou collaboration: “It allowed for a complex and rich framework—the only way of tearing down walls and crossing rivers and tunnels without visas is with the powerful flights of imagination.”

Timboctou was presented both in the U.S. and in Mexico, but there were formidable challenges. “One actor on our end dropped out because of fears of working in Mexico,” Chibas recalls. “When we were in Guadalajara doing the second workshop, I mentioned that we were looking for places in the States to take the show, including Arizona—and one of the Mexican actors said, ‘No, please not there!’ We all have our fears, justified or not, but the coming together of the company after that moment was a great success.”

Acosta is best known for his work as founder and artistic director of Teatro de Arena, a company he founded in 1989 that has participated in Muestra Nacional de Teatro (Mexico), the Festival of the Americas (Canada), the Centro American Theatre Festival (El Salvador) and the Festival Iberoamericano de Teatro (Colombia) as well as in festivals in Portugal and Spain. In the summer of 2014, Acosta directed La velocidad del zoom del horizonte (literally, “The velocity of zoom of the horizon”), a production influenced by the Stanislaw Lem novel Solaris. This sci-fi play experimented with the themes of isolation and human contradictions using the narrative styles of Chekhov and film director Lars von Trier.

“Art is a uniquely human phenomenon that connects us all,” says Acosta. “And theatre puts man and humanity at the center of discussion.” Hesitant to fully declare what he loves to do as theatre of any one type—absurd, oppressed, classical—he emphasizes the importance of curiosity. “Artists are islands, always reaching for connection, and there is something beautiful in finding, through that isolation, the need for connection to other artists with whom we’ve had valuable artistic dialogues.” He’s talking, he says, specifically about his collaborator Chibas.

After Timboctou, Acosta and Chibas will start working on a documentary film/theatre project entitled Residency:SHELTER. This performance hybrid goes after the heart of displacement and the dispossessed by delving into the human crisis of immigration—specifically, the child refugees and the deportation shelter system in the U.S.

When asked about the artistic methodologies they used to excavate the dark and nasty truths of how the Mexico and U.S. handle immigration, Acosta acknowledges that ignorance is his “entry point.” He admits to what can be described as a type of selective myopia, a symptom common to inhabitants of turbulent and dangerous landscapes—i.e., the current state of Mexico—in which certain realities that may cause feelings of despair and forms of guilt are ignored.

It is through collaborations like Residency:SHELTER, he ultimately believes, that artists can discover answers to questions like “How did this happen?” and have the necessary distance to process that answer. It does not matter whether the question refers to the treatment of immigrants, to the growth of guerrilla forces, to the drug wars or to the overall violence in Latin America. It is no secret that violent outbursts in the last 30 years have cracked Latin America’s social and cultural mantle, and have erupted into consequences that transcend borders.

“We are all involved in this,” believes Acosta. “Even if artists themselves are islands of thought, it is theatre that has a responsibility to unite us and make us face the consequences of our individual actions, together.”

A Revolution in Motion

Since 2001, Tricklock Company of Albuquerque, N.M., has curated, organized and hosted the Revolutions International Festival, a month-long celebration of global theatrical culture. Just this year, Revolutions presented the works of Leev Theater Group of Iran’s Hamlet, Prince of Grief, Mujeres en Ritual Danza-Teatro of Mexico’s Antigona en la frontera (Antigone on the border), a reading of Idris Goodwin’s play Bars and Measures and a series of variety-show cabarets in which all of the participants in the festival are encouraged to perform and collaborate with Albuquerque audiences and theatremakers.

Some would argue that a festival does not inherently indicate collaboration; but returning to the story of the seed, Revolutions qualifies as an earthshaking stampede of cross-fertilization, the kind that is most necessary in arid regions in order to stimulate growth. It is responsible for invigorating conversation and the seeding of future collaborations among the participating companies—ideas are planted over brews, music and conversation.

“The unifying theme is that we all have an impulse to tell a story—and sometimes we don’t even know what story is there until we are face to face with one another,” declares Tricklock artistic director Juli Hendren. “I find that for artists, this impulse starts with a simple conversation of what is happening in their home country.”

One such story is what initially launched a 2012 collaboration between Chicago-based playwrights and directors Seth Bockley and Devon de Mayo and the Mexican clown trio La Piara Teatro. The La Piara company, according to Artús Chávez, one of its three originators, was “accidentally founded” in 2008 when he got together with Madeline Sierra and Fernando Córdova to explore the possibility of making a new clown show. Bockley and de Mayo, recipients of a TCG On the Road Grant, traveled to Mexico and were eventually able to take La Piara to Chicago a total of three times. In 2013 La Piara performed the product of this collaboration at Revolutions—a clown play titled GUERRA (WAR).

“La Piara is a group of three strong-willed, independent artists and creators who have a remarkable and uncanny chemistry onstage,” says Bockley. “As Mexican artists, they have a strong sense that art should necessarily be politically engaged. All three members have traveled, studied and toured in Europe and South America, and they have a profound hunger to bring back new knowledge and techniques to their practice in Mexico City. My hope is that our increasingly integrated continent could allow for even more free flow of artists and long-term artistic exchange.”

GUERRA has been presented at places like Millennium Park Stage in Chicago and the Tank in New York. According to Chavez, New Mexico audiences were moved by the piece in profound ways, in no small part because of the depth of the shared roots inherent in territories not too far from the U.S./Mexico border.

Chavez goes on to note that La Piara specializes in amplification through simplification—in other words, in theatrical clowning, which deepens perspectives on social issues by entering dangerous topics like war, greed and corruption bearing the white flag (probably made of a used kerchief) of the “buffoon,” who can innocently undermine authority. “Why make serious issues more serious?” says Chavez. “Comedy allows for a safe distance that allows us to see things in better perspective and with more objectivity.”

Beneath the Surfaces

The story of the seed is one of regeneration in the darkness. Mexico, like most of Latin America, remains shadowed by a northern sister whose artistic constituencies are reaching out at last. Mexico remains in what seems like an eternal drought of corruption and violence, a spell that these collaborations can only hope to break.

Will the creative path and the sharing of artistic resources begin the process from divided introspection to collective understanding? What are the implications of a revival of an ambulant mask and physical theatre? Of the realization-through-repetition reconnection of two artists debunking the realities of immigrant shelters? Of the interjection of three clowns on very touchy subjects? What are the implications of all those other collaborations omitted from this story?

“Theatre unites people, and, as a result, it favors the growth of healthy societies,” Chavez maintains. “It’s never the same to enter into a county as an unwanted, or as a tourist, as it is when you are invited to that country as an artist. The intake of the foreign culture and the intimacy you share with that society is different.”

“As Americans, we gain enormous perspective through the experience of collaboration with artists from other countries,” adds Bockley. “Aside from the unique practices and traditions they may offer, the simple fact of unmooring ourselves from the familiar is critical for artistic growth. We desperately need to ensure that our theatre tradition is influenced and challenged by advances and experiments happening in live performance all around the world.”

Georgina H. Escobar is from Ciudad Juárez, México. She is a member of the Latino Theatre Commons, Cafe Onda Editorial Board and founder of Grettlegrott Ink & One Blue Cat Productions.

For a listing of more U.S./Mexico collaborations, go here.