The voice on the other end of the phone is modulated with the faux calm unique to consultants and headhunters. “The theatre does indeed lie in ruins, but the potential is enormous. The rebuilding campaign is a thrilling opportunity to reintroduce A.C.T. to the community. The cost is estimated to be upwards of $30 million.”

Behind me on the floor, my two-year-old daughter Lexie is drinking soy sauce directly out of the bottle, gurgling happily. It is 7 p.m. in New York and she hasn’t been fed yet. I cradle the phone with one cheek and deftly swipe the soy sauce from her hands, substituting an animal cracker to buy five more minutes of transcontinental conversation.

“The search was well underway when we got your letter, but the board is definitely intrigued. We think you should come out immediately and meet the search committee.”

It was October 1991. I had a babbling two-year-old, a job I loved at a beautiful but indigent small theatre in New York, and a husband whose career in Soviet foreign policy had been prematurely cut short by the fall of the Iron Curtain (“End of the Cold War: There Goes My Career” read the T-shirt I gave him at the time). America was slowly dipping into recession, but something in me had instinctively sent a brief letter of introduction to the search committee of a famed but troubled institution in San Francisco, suggesting that I might be an appropriate candidate to helm American Conservatory Theater.

I was not a stranger to destitute nonprofits. The day I took over the Classic Stage Company in 1986, I discovered to my horror that no payroll taxes had been paid for several years and ConEd was about to turn off the power due to outstanding bills. My first task as artistic director was to hire the heaviest actor I knew (no names named) to sit on the sidewalk grate outside the building, in order to prevent eager meter-readers from descending to the basement to quantify our negligence. I attempted a crash course on tax law while directing Tony Harrison’s Phaedra Britannica by day, as we slowly wiggled out from under our disastrous tax burden. Over time, CSC had come back to life through blind chutzpah, a great deal of cajoling and a Harold Pinter premiere. I figured A.C.T. was just worse on a magnitude of five…

Thus, two days later, I ended up on a plane to California with my loquacious two-year-old in tow. I told my beloved CSC colleagues that I was going to see my mother, a Stanford professor, for the weekend. The chances of anything materializing at A.C.T. were so slim it seemed needless to tell them the truth.

On the plane Lexie played Pat the Bunny and I conjured up everything I knew about A.C.T. As an undergraduate at Stanford in the late ’70s, reveling in my newfound obsession with Meyerhold and the Russian formalists, I had seen A.C.T.’s production of The Seagull in the last row of the second balcony of the Geary Theater, and remember those booming, well-trained voices carrying to the back of a deeply uncomfortable row of wooden benches that constituted the cheap seats in that otherwise spectacular theatre. (I do remember that there was no sound barrier between the Geary and the commercial theatre next door, and that when their musical finished that evening at the quietest moment of Chekhov, right before Kostya shot himself, the crowds tramped loudly down the fire escape stairs outside and the moment was lost. That was one of the first things I wanted to fix when we renovated the Geary Theater all those years later.)

Because my drama professor Martin Esslin (author of The Theater of the Absurd) was also a resident dramaturg at the Magic Theatre, I had spent more of my undergraduate years going to see experimental theatre at Fort Mason than attending A.C.T. A few years later, rumors began circulating that Bill Ball, founding genius of A.C.T., had died of a drug overdose, and I knew that his second-in-command Ed Hastings had returned to take over the theatre.

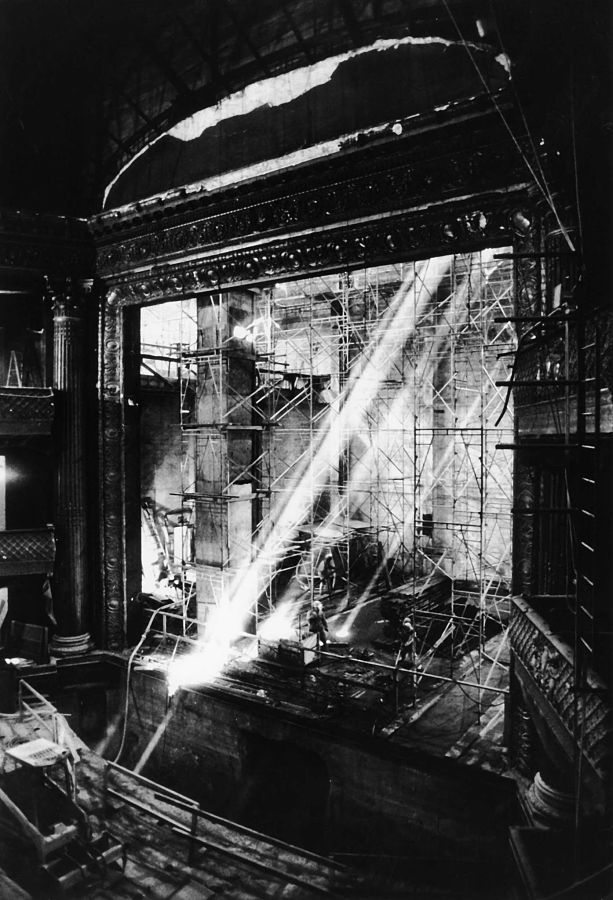

Of course I also knew that on Oct. 17, 1989, the gorgeous 1910 Beaux Arts Geary Theater had collapsed in the Loma Prieta earthquake. But I knew, too, that in the late ’60s, something legendary had happened with the founding of A.C.T. in San Francisco, something idealistic and pure and brave that focused on great actors, great literature and lifelong learning. More than that, pre-Google, I couldn’t easily bring to mind.

I got off the plane on that fall day in 1991, deposited my daughter with her soulmate grandmother Marjorie in Palo Alto, and drove up Highway 280 to interview with the A.C.T. search committee at the Bank of San Francisco. I saw signs for Half Moon Bay above a glistening blue reservoir, and wondered where the hell I had been for the past 15 years.

So here I was, driving north in a rental car and a borrowed suit, trying to look vaguely professional and rehearsing a few key declarations of principles in my head as I navigated my way downtown. San Francisco seemed like a toy city that day, intimate and charming and somewhat inscrutable. The Bank of San Francisco is now defunct, but at the time it sat in a grand pile on a distinguished street corner across from the Transamerica Pyramid, a reminder of the robber baron days when Leland Stanford and Collis P. Huntington ruled the city. In a big sunny boardroom, six trustees were waiting for me.