John Kander and Nick Blaemire can’t stop talking about Kansas City.

“That’s my town!” the celebrated composer of Cabaret and Chicago exclaims after learning that Blaemire’s most recent musical, A Little More Alive, premiered at Kansas City Rep. Kander, who turns 88 next month, grew up in the Missouri town.

“I really loved it there,” the younger composer says. “I think I gained 15 pounds in a matter of three weeks.”

“How much of that was barbecue?” Kander asks immediately.

“Eighty-eight percent!” Blaemire, 30, responds, as the two laugh and trade notes on the best joints in the area. (Arthur Bryant’s Barbeque wins.)

It’s hard to believe this is the first time the two have ever met, as (despite a 57-year age difference) they banter like old friends. And this afternoon at Kander’s Upper West Side brownstone is likely to be the first of many meetings, as each has a new musical premiering at Virginia’s Signature Theatre this month as part of the company’s 25th anniversary season.

Kander’s Kid Victory, which he penned with Greg Pierce, runs Feb. 17–Mar. 22, and explores the repercussions of abduction on a young boy returning home. Pierce and Kander previously collaborated on The Landing, which ran at the Vineyard Theater in New York in 2013, and that company will coproduce Kid Victory with Signature.

Blaemire’s Soon, which starts performances at Signature on March 10, takes a look at youth and ambition in the face of the apocalypse.

The two are already making plans for when they’ll both be in Virginia, Blaemire’s native turf this time, and since Blaemire’s show will be rehearsing upstairs, Kander wants to make sure there won’t be too much noise coming from above. “Don’t worry, it’s a mime show!” Blaemire jokes.

Both composers have a history with Signature—Blaemire’s first musical, Glory Days, which he penned with James Gardiner, now the theatre’s publicist, opened there before transferring to a short-lived (read: one performance) run on Broadway. Kander has had several of his musicals produced at Signature, including a production of The Visit starring Chita Rivera in 2008. The star will take that musical to Broadway this spring, bringing Kander’s current tally on the Great White Way to three shows, counting Cabaret (closing this month) and the long-running Chicago.

However, Broadway is a testy mistress. When American Theatre sat down with the writers for an hour of chatting, the two shared not only a mutual admiration for each other’s work but a mutual hopelessness about what it means to pen a blockbuster musical—or whether it’s even worth it.

Nick Blaemire: I’ve been a fan of yours since I was a wee lad.

John Kander: I hate that! It’s a reminder that I’m going to be 88, and so what the fuck? [Laughs]

Blaemire: Let me rephrase it then. When I was 11, the first show that I saw at Signature was Megan Lawrence and Steve Cupo doing Cabaret in the garage. And that’s the reason.

Kander: So you’re a D.C. person?

Blaemire: I grew up there. Signature was the first theatre that I ever spent time in. I remember that Nazi flag falling at the end of Cabaret and being like, “What is this?” I haven’t seen anything like it since. [Signature artistic director Eric Schaeffer] managed to get gritty before everyone else, and now everyone’s kind of copying him in some diet way.

Kander: I’ve known Eric and loved that theatre for years. I guess I’ve worked there seven times.

SUZY EVANS: How did Kid Victory come about?

Kander: It’s hard to say. Greg and I decided that we will always be writing something. We make up stories. Greg went to Oberlin; I went to Oberlin—50 years apart from each other. But there is a kind of Oberlin… not mafia, if you will, but a sort of connection with a lot of the Oberlin theatre people who come here. We wrote a story that we used in The Landing, and then we decided to make three of them—I can’t tell you which one of us suggested it first, but we came up with the idea that you read about abductions all the time but you never follow up on them. There will be a big flurry of, “What happened? This terrible thing! Have we got the guy yet?” But nobody really talks about what happens after somebody who’s been abducted comes home and is trying to fit back into society. We investigated a bit and sure enough, for the most part, there was very little information about these kids. It intrigued us. [Apartment buzzer rings.]

Blaemire: I just told my family they could stop by.

Kander: What are we serving?

Nick, Soon is about the Earth melting. How did you arrive at that idea?

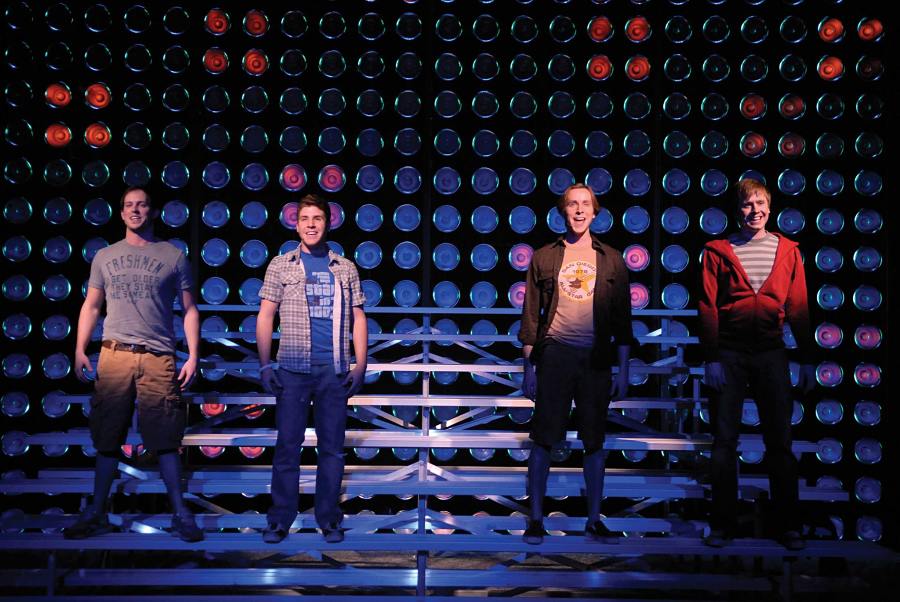

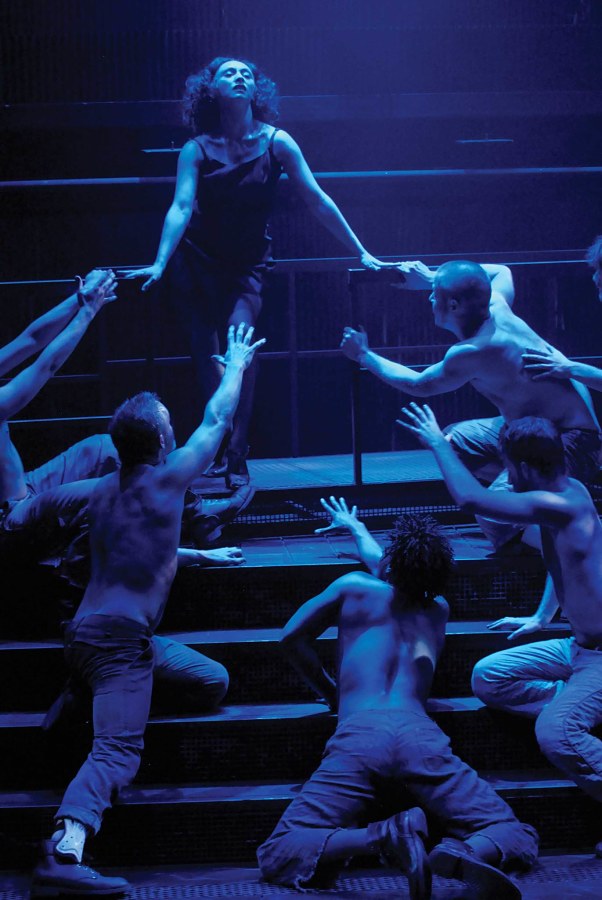

Blaemire: One of the things I’ve been trying to figure out over the past few years is how to make theatre that is producible and about things that I care about in a serious way—but that can also be a musical. That is something that I feel has been a part of the your mission statement for so long—it’s a thing that Cabaret set a tone for in my life. It showed me it’s possible to use music to talk about something that’s not glib or that’s not extraordinarily epic—that a small story can have an epic reverberation. That’s very much what James and I tried to do when we wrote Glory Days together when we were kids, and it’s very much the basis for Soon as well. The show is four people in a unit set apartment, just trying to figure out how to deal with the world getting hotter.

Kander: The science isn’t absolutely clear on that…

Blaemire: You’re right. Those three-percent Republican scientists are really holding back the progress! And they’re not allowed to come to this play. It’s also about my lack of response to the situation—I’ve been like, “Oh, God, that’s very scary. Let me go back to what I was doing.” The show’s about this girl who doesn’t want to leave her apartment now that she knows that world is ending, giving her an excuse to let go of ambition—which really only has a reason to exist when you think you’re going to be around for your whole life. If you know that it’s being cut off in the middle, it changes the scope of your arc.

The only trick is that she’s got a new boyfriend, who wants to take her away and spend these last few months together—he becomes the catalyst for this cavalcade of memories that have to do with a lack of faith in herself, which leads to using this apocalypse as an excuse. It’s been an interesting way to talk about stuff that goes on with people my age and the responsibility of making good on the things you said when you were younger, and realizing that the world is not built for your story to be played out. And there’s poetry in that, too.

That’s something that you’ve really done a beautiful job of showing, Mr. Kander—even in these bleak settings that make you think, “Oh, God, there is no magic in the world,” there’s everything there. It’s not just horrible. It’s not just amazing. Life is a big fat mess.

Kander: It’s a terrific idea. What are you using instrumentally?

Blaemire: We’re going to do four. Do you know [music director] Charlie Rosen?

Kander: Yes, Charlie “Mr. Everything”! He’s extraordinary. I hope he’s going to be in The Visit.

Blaemire: He’s definitely going to be in The Visit. In fact, we’re figuring that out because The Visit band rehearsals start when we’re in previews. You’re stealing him, thank you very much.

Nick, you mentioned musicals about topics that are either difficult to talk about or smaller in scope. Mr. Kander, this seems like something you really pioneered, with shows like Cabaret. Was there resistance when you were first exploring that?

Kander: It’s quite the reverse of what people tell you is easy or hard. You know what’s hard? Really hard? Boy meets girl, and they break up, and they get together again, and then go off to Las Vegas. That’s really hard to do. If you’re working on something which has some meat in it, the possibilities are rich, and you find yourself having to scrape away ideas more often than having to invent them. I secretly chuckle when someone says, “Oh, how brave you are for tackling these subjects!” When we wrote Woman of the Year or The Act, that was hard because there just wasn’t much there to work with. I don’t think they were terrible scores, but they certainly weren’t our best. And they were the hardest to write.

So why is it easier to write something that’s darker?

Kander: It’s not about dark—it’s about thick. Greg and I are working on a musical version of The Enchanted and it’s a comedy, but it’s a meaty piece. And that’s given us a lot to work with.

Blaemire: You’re totally right. I’m fascinated by that idea of a very simple telling of something that we all either don’t want to admit we go through, or that we go through and no one’s articulated. I’m horrible at inventing reasons for people to want to be with each other—I feel like plotting a show is just murder. Creating something where the idea is the most important minimizes the amount of running around you have to do, or that the characters have to do, and it also gets you closer to talking about the things you think are interesting.

Do you feel like musical theatre has changed since you started writing shows, Mr. Kander?

Kander: I don’t really know. I just do what I do and try to make theatre. I stopped reading articles about the theatre almost completely a long time ago, because either they were either going to upset me or I was going to find myself thinking, “So and so writes this way, no wonder I’m so untalented.” You just have to be yourself. And if you’re lucky enough—and I have been lucky—a few things come around and are successful enough so that you can eat. And then once you can put food on the table, everything above that is sort of dessert, so you stop thinking about career and start focusing where your focus should be—which is on the work.

Nick, as a young writer, do you feel like there are outside pressures as you’re working?

Blaemire: Not reading those articles is definitely a tricky external/internal negotiation, and the big one in my life is staying off Facebook, because the minute I go on there, I become a member of society, and a member of “young people who are trying to write musicals,” and join this race to do something that makes you popular to people who didn’t like you in high school. Many times through my 20s, I got really caught up in it, and one of the best things that has happened to me lately is turning 30. You get so caught up in the bullshit that it takes to get a show done that you lose sight of the reason that you did it in the first place. I’m really trying to rebalance that because, as you say, it’s upsetting and not the point—the minute it turns into trying to push a show and trying to convince people to come…

Kander: Eeeee!

Blaemire: It gives me the heebie-jeebies!

Kander: I want you to know now, you’re very young, it will never get better. [Laughs]

Blaemire: Well, shit.

Kander: There is no golden world out there, nor will you ever get to the point where you feel competent. There will never be a time where you say, “Oh, I can do this!”

Blaemire: That’s very comforting to hear. Although I’m getting very used to my lack of confidence—I’m sort of like, “Well, this is what I got.” It is nice when you hear something you’ve done, and you’re like, “Well, that’s what I meant to do!” And then people make it better.

Kander: It’s useful to have a people around who say it’s all right. You don’t have to have a lot of people, but you need a few. There’s a line in Our Town where Emily is asking her mother, “Am I pretty?” And her mother says, “You’re pretty enough for all useful purposes.” [Laughs] So I think we need to feel that we’re pretty enough for all useful purposes.

Can each of you talk a little about your writing process?

Kander: You start with the idea, that’s it. Then, it depends on whether you’re working on something by yourself or with other people. You collaborate, and collaboration can be a wonderful thing. Collaboration means talking and talking and talking, and it also means being able to listen. Fred [Ebb] and I were very, very different people, but when we were working, it was like we became something else. We were both very thin-skinned, but when we were working, we could say anything to each other. It was always about building together, and we actually never had a fight. We argued, we had fights, but when we were writing, there was always the possibility that the other person was right. And if one of us was passionate about something, we would go with it.

Blaemire: That’s a beautiful answer. I’m getting better at finding my own answer. The past 10 odd years, it’s been a lot of just doing whatever felt right and then backtracking and realizing it might not have been the most optimal way to put the thing together. I’ve been writing this current musical for six years. When I started talking to Matt Gardiner, our director, I immediately felt this total wave of relief, because I’ve been trying to answer these questions by myself for so long—Matt has just been such a joy in terms of pushing me, not because he thinks I’m not doing a good enough job, but because he thinks that I’m onto something. We’re both looking at the show, as opposed to proving something about ourselves to each other, which is gross. I’m really trying to stay away from people who come at this to fix some agenda in themselves, and it really gets in the way of the work.

Both of your shows premiering at Signature are original musicals, not based on any pre-existing source material. Do you find it easier or harder to do something new?

Blaemire: I find it more exciting. I think it’s harder for people to figure out how to sell something like that, especially in a market where there are only so many seats and only so many times you can see it. But that’s the thing about Eric that is so incredibly rare in this field—he’s somebody who’s done upwards of 30 world premieres, more than one a year for many years, because he thinks it’s more interesting to do something risky that might be new as opposed to regurgitating something old just to make sure that you hit your quota. And that’s not necessarily possible in every realm of this business. I mean, Broadway shows are expensive, and that’s a different market. I’m certainly not writing this show to go to Broadway, necessarily.

Kander: I don’t know if I ever will again, really. I grew up thinking that what I was writing was for Broadway theatres. I don’t know what that is anymore. I don’t know if that will ever happen again.

Blaemire: In Soon, we’re trying to figure out how to make some theatre magic and do some visual things that are exciting, which costs money. But I would never want to sacrifice the things that I think are weird or individual about the show in order to get it to that place. It’s a complicated juncture to walk, because you’re saying, “This is going to make me less money.” That has become very clear to me. It’s more important for me not to end up looking at a vanilla version of my play. I’d like to think that it’s possible to make a living and make something that you’re really proud of.

Kander: I think that we’re stuck.