Approximately 115 million people will watch the Super Bowl this year. That’s an astounding number, almost too big to conceptualize. If you’re one of them, you’ll be taking part in the largest shared experience we have as Americans—one that dwarfs every other televised event, and certainly any live form of entertainment.

Because the NFL has so many fans and such a wide reach, the issues and controversies that arise around it, particularly in recent years, have an outsized impact on American life. It’s surprising, then, that the theatre—in contrast to movies or television—has rarely portrayed the complexities of this great American sport.

There are certainly dramatic portrayals within the American stage canon of the football star. Think of Biff, a football hero full of promise, in Death of a Salesman. Though he’s secondary to the play, Biff’s image as a ruggedly attractive young man tossing a pigskin resonates instantly with an audience. That glimpse alone signifies him as masculine, desirable, all-American.

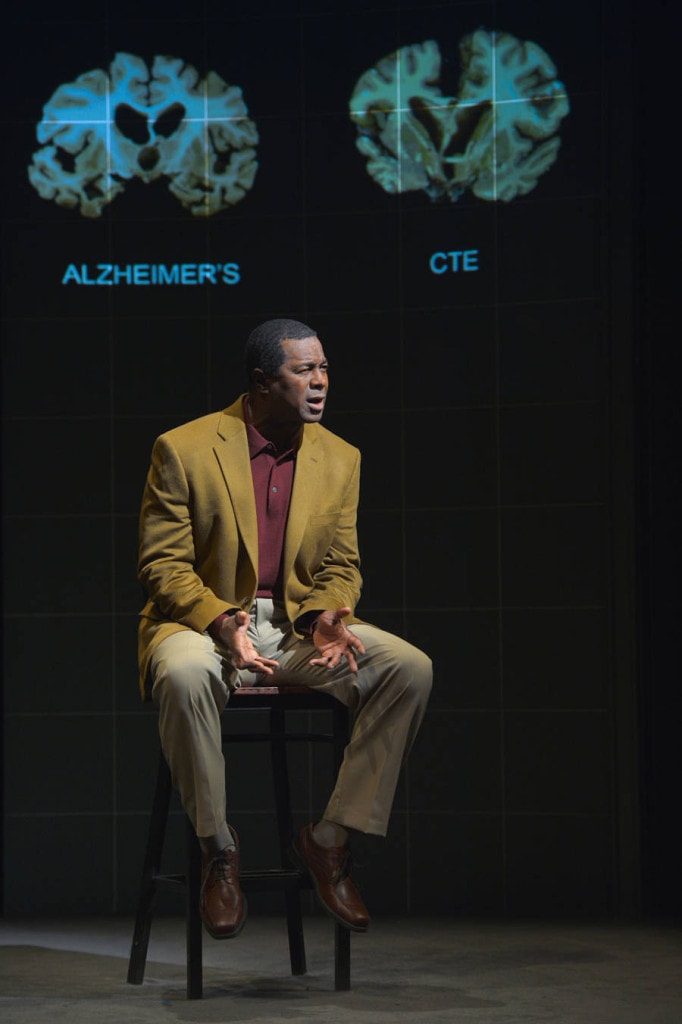

But much as, upon closer examination, Biff’s gridiron glory masks a more complicated reality, football is not all touchdowns and high-fives. Increasingly, even diehard fans are taking a second look at the NFL’s actions as a corporate enterprise, and at the health implications of football the way it’s currently played. Within the past six years, new evidence of the sport’s damaging toll on the brains and bodies of players has emerged. Doctors are now certain that concussions caused by hundreds of head collisions can lead to dementia, early-onset Alzheimer’s and C.T.E. (Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, a brain injury detectable in autopsies). In August 2013, following an unprecedented class-action lawsuit, the NFL paid a settlement of $765 million to 18,000 former football players with brain trauma.

On the heels of these events, theatre artists have entered the conversation—not to condemn the sport, necessarily, but to discuss and explore its complications. This season alone, three world premiere plays take on the subject of life-changing injuries in football: X’s and O’s: A Football Love Story by KJ Sanchez and Jenny Mercein; Colossal by Andrew Hinderaker; and Clutch by Liz Shannon Miller.

These plays promise audiences a different experience than, say, Lombardi, Eric Simonson’s theatrical depiction of the venerated Green Bay Packers coach, which played on Broadway in 2010 (and has been popular at resident theatres). While the upbeat Lombardi ostensibly aimed to draw football fans to the theatre, these other world-premiere plays aspire to engage the public in a discussion of mental health, violence and sexual identity within the culture of football—perhaps not the lightest of fare, but weighty subjects worth tackling.

Andrew Hinderaker has watched football devotedly since he was a child in Madison, Wisc. After spending a number of years as a playwright in the Chicago storefront scene, he entered the theatre MFA program at the University of Texas at Austin. Studying under Kirk Lynn, head of playwriting and directing at UT’s Department of Theatre and Dance (and a Rude Mechs founder), Hinderaker was inspired to attempt a new kind of play: something large-scale and experiential.

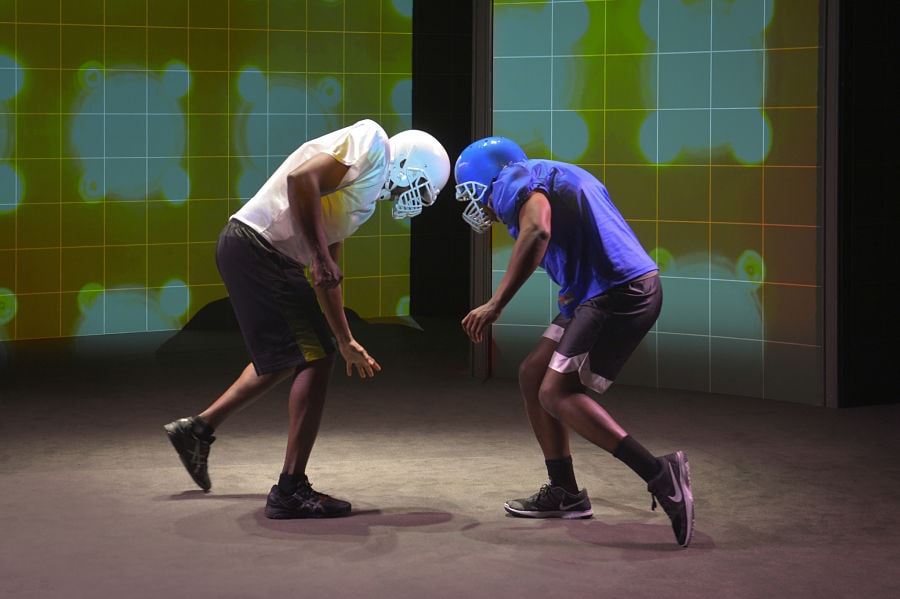

The outcome was Colossal, and, from its inception, the play has been true to its name. Each production requires anywhere from 13 to 24 performers, a live drumline, fully padded football uniforms and a set that features a scoreboard with a ticking clock to demarcate 15-minute quarters. These are all factors that add to production costs but aim to create an immersive, adrenaline-filled experience.

Hinderaker’s hope is that “when the audience walks into the theatre space, whatever expectations they have are dislodged,” he says. “I didn’t just want to create a play—I wanted it to be a theatrical event.”

The play, which received the Kennedy Center’s Jean Kennedy Smith Playwriting Award and is currently in the process of a National New Play Network rolling world premiere, runs next at Dallas Theater Center (April 4–May 3), in a production by DTC’s artistic director Kevin Moriarty.

Colossal takes on two hot-button sports issue in its portrayal of a gay college football player whose aspirations of playing pro are crushed when he irreparably damages his spinal cord on the field. The narrative is both an examination of the punishing effects of the sport and an exploration of gay identity within a homoerotic yet hyper-straight male culture.

Hinderaker wrote the lead role for his friend Michael Patrick Thornton, who uses a wheelchair in real life. Indeed, adding to the play’s built-in production challenges, Hinderaker has specified that only disabled actors should play the part. He explains, as the play begins, “There’s the opening kickoff, and the action freezes and the post-injury version of Mike comes wheeling through, and you realize you’re watching footage of the opening kickoff where he got hurt.”

Hinderaker says that Colossal was written to be both thrilling and sobering. “We are drawn to something that is inherently incredibly violent,” Hinderaker says. “And not only are we willing to continue to be fans, but we’re drawn to it because of that detail.”

With a similar impulse to understand the culture of football, playwright KJ Sanchez teamed with actor and playwright Jenny Mercein to create X’s and O’s (A Football Love Story). Both longtime fans (Mercein is the daughter of Chuck Mercein, who played seven seasons in the NFL), the two quickly found that they shared shock and sadness over the death of Junior Seau, a former player who committed suicide after grappling with brain trauma.

Sanchez, who coauthored ReEntry, a docutheatre piece about U.S. war veterans, joined forces with Mercein to create a play exploring their ambivalence about the game. Sanchez’s theatre company, American Records, relies on interviews to create plays, and X’s and O’s was no exception. But after a thorough research and interview process, Sanchez and Mercein found that they were undecided on the play’s central concept.

“Then we started to talk to the wives, and they told us these heartbreaking stories,” Sanchez says. These were football widows, essentially, whose husbands had come to tragic early deaths and were diagnosed postmortem with C.T.E. Perhaps surprisingly, Sanchez says, “They also talked about still loving the game. That’s where the title came from—I understood that the story is all about love.”

Indeed, X’s and O’s is hardly an outsider’s attack on the sport. In addition to Mercein’s coauthorship, the production—which runs through March 1 at California’s Berkeley Repertory Theatre under artistic director Tony Taccone’s supervision—stars former NFL player Dwight Hicks.

A third new work on the subject takes the stage in Los Angeles in March. Liz Shannon Miller’s Clutch, at SkyPilot Theatre Company, tells the story of Gordon Beers, a fictional wide receiver who reaches the height of fame in the 1990s, then begins to deteriorate in the following decade due to brain injuries.

The audience never meets Gordon, though; the one-act play is set entirely at his funeral, where his grown children, sister and nephew as well as his doctor gather. The doctor wants to study his brain, but his children have planned to cremate him.

Miller, who grew up in the Bay Area as a passive football observer—Sunday games on her home TV were a staple when she was growing up, she says—made up for her lack of inside knowledge in a novel way. “I’ve done a lot of writing on this play in bars and coffee shops, places that are playing the game, so that I can lean over and say, ‘I don’t understand what just happened.’ The thing with football is that the rules are so immense and complex that to understand it in full would be a lifelong goal.”

She says she’s found that the inherent drama of the game provides “such a clean narrative—there are two teams, and one of them wins and one of them loses. The emotional stakes of winning and losing are incredibly helpful in trying to construct a story. With this piece, it’s about someone who loses entirely.”

Miller got the idea for the play from a 2009 GQ magazine article called “Game Brain,” possibly the first piece of mainstream journalism that examined and publicized football-related brain injuries. The article detailed the research process of pathologist Bennet Omalu, who first detected C.T.E. in the brains of former football players who died or committed suicide. (The American public will soon become much more aware of Dr. Omalu’s obstacles and contributions when Will Smith plays him in an upcoming film with the imaginative title Concussion.)

In the years since Hinderaker, Sanchez, Mercein and Miller began working on their respective plays, the NFL has introduced new regulations—most notably, the removal and medical assessment of players with concussions. Almost eclipsing this issue in the past year, though, were reports of domestic abuse by football players, which fueled a controversy not only for the reports themselves but also because of the league’s bungled handling of the allegations. In Sanchez’s view, the latter subject merits its own play, as well as a vocal response from the public.

“I think that fans should do everything they can to let the NFL know what they think is good business and what they think is improper,” says Sanchez, referring to both the league’s handling of players’ brain injuries and their domestic violence. While these football-related plays don’t espouse direct agendas for the game, each advocates in its way for a game that can maintain its integrity and still be thrilling to watch. What X’s and O’s, Colossal and Clutch have in common, beyond mining stage drama from the game and its players, is the compelling notion that fans can raise their voices to do more than cheer. They can impact the very nature of the game—even when the challenge seems more imposing than a wall of defensive linemen.

Lonnie Firestone is a frequent contributor to this magazine.