The pressure is on Jarosław Fret, and he knows it. If the 43-year-old artistic director of Poland’s Teatr ZAR were a juggler, these are some of the balls he’d be hustling to keep in the air:

- The unprecedented success of his groundbreaking new work, Armine, Sister. The production, debuted last year by the Grotowski-inspired ensemble Fret founded 12 years ago, has earned wide critical acclaim in Poland, including Teatr magazine’s 2013 award for best production of the year. The gripping, musically virtuosic piece—an evocation of the near-extermination of the Armenian people by the Turks in the early part of the 20th century—is slated for repeat performances next month (Feb. 20–23) in ZAR’s home town, Wrocław; in Oslo (March 4–6); and on an upcoming international tour, including performances May 24–30 in the U.S., at the San Francisco Arts Festival.

- The year-round buzz of activity he supervises at the Grotowski Institute. Fret doubles as director of this historically significant theatre-development organization, which he has shepherded (with the help of ample funding) from its modest digs in Wrocław’s elegantly restored central square to a spiffy new multipurpose facility across town on the tree-lined banks of the Oder River.

- Coordination of Wrocław’s celebration as 2016’s European Capital of Culture. Supervising this multifaceted effort, dubbed “Spaces for Beauty” and intended to actively involve Wrocław’s citizenry, is Fret’s newest and most complicated role, and it has embroiled him in a squall of media controversy that shows no sign of letting up in coming months.

The controversy first: From the moment back in 2011 that Wrocław won its application for culture-capital status—a gateway to continent-wide prominence and increased tourism for the city, Poland’s fourth largest—there were quarrels behind the scenes and in the press. After one director of the project stepped down and a second (activist theatre figure Krzysztof Czyzewski) was asked to resign by the European commission in charge, the project was turned over to an eight-member board of curators (Fret among them), each responsible for a different cultural area.

Read Jim O’Quinn’s in-depth feature on ZAR’s collaboration with Cutting Ball Theater here.

But when critics continued to carp about political cronyism, the lack of a unified artistic vision for the celebration and the planned importation to Wrocław of “transplants” like the itinerant European Theatre Olympics, the commission reacted by elevating Fret to the solo role of coordinator. Charged with representing the board in negotiations with the commission, the city and state Ministries of Culture and the myriad cultural interests involved—and presented, after the 2014 elections, with a radically downsized budget to work with—Fret was in effect left holding the bag.

The culture-capital festivities are still nearly a year away, but Fret’s preliminary efforts have done little to quiet the naysayers, who continue to object to such tactics as the reductive skewering of “culture” into its traditional categories (music, visual arts, theatre, etc.); the emphasis on splashy, star-driven, pop-culture events; and the virtual omission from the program of Polish filmmaking (given that Wrocław was for a time the heart of the Polish film industry). Fret affirms that he wants to feature the nation’s new, increasingly political generation of theatre directors and playwrights and to help companies under financial duress, but his inattention to endangered stalwarts like Teatr Polski (the Wrocław house where Krystian Lupa regularly directs) has cast doubt on his commitment to inclusiveness.

Nevertheless, Fret’s triple-threat status has brought him new recognition, nationally and beyond, not least for the creative strides on display in Armine, Sister.

The production, timed to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the advent of the Armenian genocide in 1915, is ZAR’s first to incorporate performers from outside the troupe. The additions include master singers from Iran, Armenia and Turkey, versed in the liturgical musical traditions of those regions. Fret unearthed these collaborators—who come, pointedly, from societies representing both the aggressors and the victims in the conflict the play depicts—over the course of recent research expeditions to Istanbul, Yerevan, Jerusalem and thereabouts, and has melded their spare, haunting, rarely heard monodic singing techniques with ZAR’s own flawless polyphonic singing. Teatr magazine’s awestruck critic called the piece “a musical masterpiece.”

Indeed, the sound score of Armine, Sister (which ZAR performs in concert and workshop settings as well as full performances) is like nothing you’ve ever heard—or that any significant number of people have heard, in fact, since Armenian singing traditions were largely lost in the ethnic diaspora that followed World War I. Reviving these nearly forgotten sounds, Fret says, is “a call for the past to appear, while at the same time it is being erased. These vocal traditions are an expression of something that for generations has been inexpressible.”

In the London performances of Armine, Sister that this writer attended, during its sold-out run in November at the Battersea Arts Centre, musicians and singers were stationed at either end of a square, dark-walled chamber with spectators seated on both sides. Sixteen giant columns girded with metal casings and connected by pulleys and hooks dominated the space, suggesting, perhaps, the architecture of a church or temple. The melancholy, minor-key droning of the singers was soon punctuated by the thunder of heavy metal doors being slammed to stage floor by the men of the company, while the women, vulnerable in white shifts, huddled together or reached out tentatively, as if for rescue or comfort, into a rectangle of light.

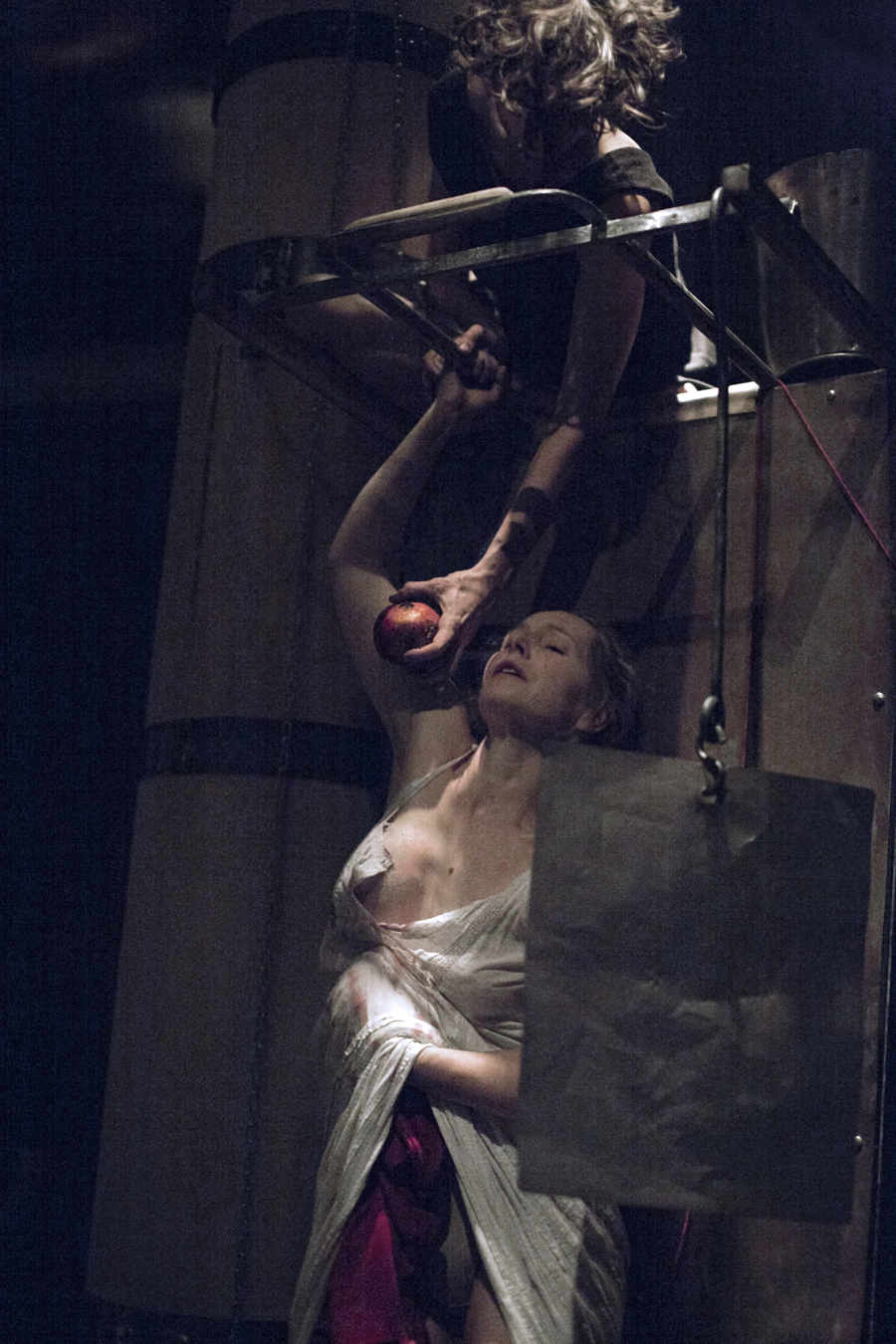

Propelled by the swelling and subsiding of the music, the action proceeded purposefully and wordlessly, like a preordained ritual. A woman plucked the flame from a candle and placed the lit wick on her breast; a photographer arrived with a tripod and great stacks of film negatives, which were soon flung derisively about the stage floor. After tentatively examining of the columns and their metal fasteners, the men stripped off their shirts and violently rearranged the monoliths, wielding ladders and cables. Some of the men violated or brutalized the women, while others were strapped to doorframes as victims. Crawling into the darkness, the suffering women retrieved pomegranates in their mouths, as the blood-red juice spilled onto their garments and bodies. And the great columns, finally dismantled with militaristic precision, turned out to be filled with sand, which spilled out in dry rivers onto the stage.

Escalating in intensity, this series of metaphoric actions—performed with the same physical precision ZAR displayed in its Gospels of Childhood trilogy, and undergirded by alternating stretches of otherworldly music and silence—ultimately emptied the space of people and things, leaving a silent, barren sandscape on which rested the still, half-naked body of a lone woman. The lights did not fade. The woman did not move. Spectators, left to contemplate the desolation, had to make their own decisions about when the performance was over, when their witnessing was done.

Given its sensational theme and the prowess of its team of creators, it’s no surprise that Armine, Sister packs a powerful punch, and will continue to do so as it makes its way in the second half of 2015 to Avignon, Edinburgh, Venice, Krakow, Berlin, Paris, Brussels and, in a final engagement that may well engender fierce debate, Istanbul. What has been perhaps less predictable is the elevation of Fret himself to new status within the Polish theatre community, for whom the Grotowski tradition that Fret emblemizes has been mostly relegated to footnote status. Will Armine, Sister’s international impact alter that dynamic?

I spoke with Fret in London about the ideas that lend Armine, Sister its persuasiveness and aesthetic power. Here are excerpts from our conversation:

JIM O’QUINN: Why do you refer to the extermination of the Armenian population in Turkey as the “first” genocide?

JARISŁAW FRET: The jurist Raphael Lemkin coined the term genocide—from the Greek “genos,” meaning race—because of this event, which happened long before the Nazis came to power. It refers to government-planned extermination—an analytical machine of death. The fact is that it was Turkey who invented the concept of the “final solution,” to prevent the Armenians from creating their own self-governing country in the region. War was just an umbrella for it.

Why are women so much the focus of this piece?

Unearthing the history of women inside the history of every war is a double taboo. It is women who suffer most from rape, from abortion, from being taken as objects. There are millions of such stories shouting to us, trying to be heard over the failures of memory and the erasures of history.

Armine, Sister is designed as a series of symbols or metaphors. What are they intended to evoke?

The columns, the 16 pillars that fill the stage, are archetypes of the Armenian church. The Armenians were great architects, who dealt with questions of harmony and proportion in both their buildings and their music. The pillars are filled with sand, representing the desert, of course, as well as the idea of a culture in ruins. When we tour, the clean sand is brought with us from Poland.

The beds and doorways, you might say, represent places of safety that will never protect you anymore. The squares of film negatives and the tripod refer to the fact that throughout the years of genocide, from 1915 to the early 1920s, someone was taking pictures—there were those you knew very well what was happening. The bread that the audience shares before and after the performance, and that the actors press onto each other in some of the scenes, is of course sustenance, but also a second skin.

Why did you decide to make the piece wordless?

This composition is like a book of poems—a big book with a million poems—but these poems are made out of air, printed on delicate material, like film negatives, that must be read against the light to be understood. It is a gravestone for those who have no graves—a gravestone both light and heavy, made of air.

Click here to see more of Magdalena Madra’s “Images from Anatolia.”