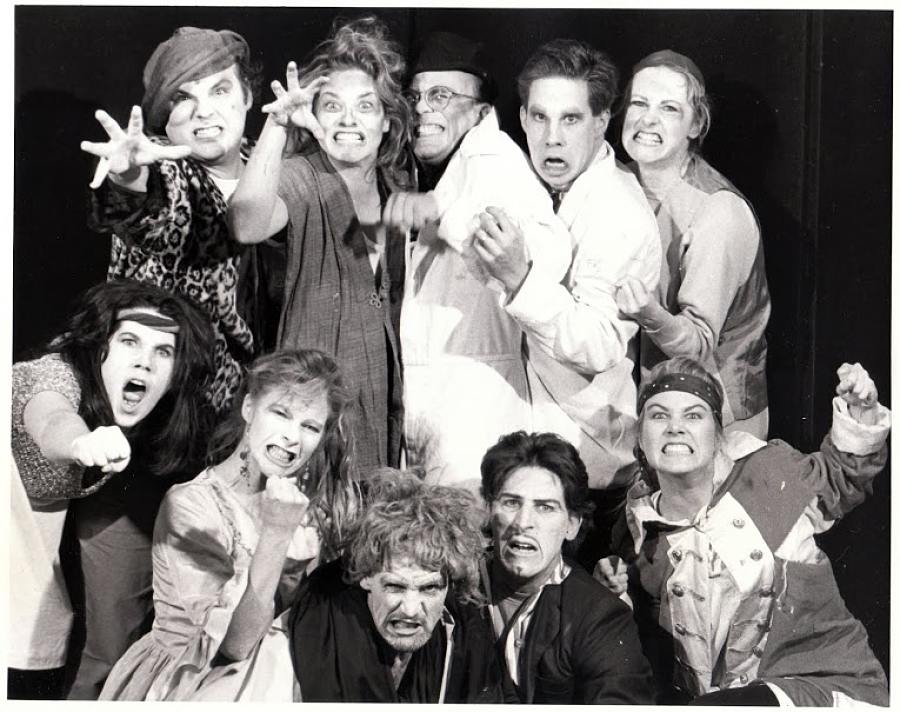

In 1981, Tim Robbins joined up with 10 fellow members of a UCLA Theater Department acting class and several players on his college softball team to start the Actors’ Gang. A team ethos still runs through the experimental theatre troupe, which has built its name on adventurous original work and raw, hard-hitting reinterpretations of international plays.

Early on, set aloft by a midnight show of Ubu the King, the ensemble would develop a piece, workshop it, and, when they got stuck, throw the piece in front of an audience. You could go to the Actors’ Gang almost any night of the week, wherever they happened to be hanging their hat, and see something nervy and new.

Then, in the mid-’80s, Robbins moved to New York and began administering the company through an intermediary director with phone calls and videotaped rehearsals. With shows like Carnage and Freaks, the Gang continued to stake out its own territory. In 1991, Robbins appointed a West Coast general manager, Mark Seldis. And then, in the seminal year of 1992—with high-profile productions of Blood! Love! Madness!, Klub and Hysteria, to name a few—the company emerged as a potent, impossible-to-ignore force in the L.A. theatre scene.

By ’93, the company had settled down. Robbins paid most of the cost of the lease and conversion of a vacant warehouse on Santa Monica Boulevard, which became a thriving complex with two theatres. It was the Gang’s first real home, and it opened with an ambitious, aggressive repertory staging of Charles Mee’s take on the Oresteia. Over the course of the ’90s, it became the home of such outsized talents as directors Tracy Young and Beth Milles and actors Chris Wells, Jack Black, Kate Mulligan and Molly Bryant.

In ’96, Robbins reduced his financial contributions, hoping to see the Gang sustain “a period of self-sufficiency.” But in 2001, as the theatre’s four-year lease came up for renewal, he returned from years of building his movie career as both actor and filmmaker (Bob Roberts, Dead Man Walking) to retake control of the theatre. After a company shake-up, he launched the Gang’s 2001–02 season with Georges Bigot’s production of The Seagull, running in repertory with his own staging of Mephisto.

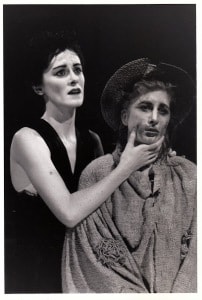

Eventually, in 2005, the Gang left Hollywood for Culver City, where they’re now the resident theatre at the Ivy Substation and an active player in Westside L.A.’s cultural life. Building on the commedia dell’arte style of Bigot’s Théâtre du Soleil, which employs stock characters, masks and white-face, the company has taken its visceral theatricality to another level. Long the lingua franca of their stage shows, the “style” has also become the language of their outreach programs, introducing theatre to schoolchildren and working with the incarcerated.

Over its rocky, often rocking, 33 years, the Actors’ Gang has mounted more than 150 productions, toured 40 states and performed on five continents. Among the landmark productions that have toured internationally are The Exonerated, Embedded, The Trial of the Catonsville Nine, Tartuffe and 1984. One of a rare breed of true theatrical ensembles, the Gang, with its 30-odd members, remains dedicated to reclaiming the stage as a shared, sacred space. And though there has been turnover in the membership, several company members from the early years are still with the ensemble, including Cynthia Ettinger (who serves with Robbins as co-artistic director), V. J. Foster, Patti Tippo, Brian Finney, Cameron Dye, Steven Porter, Ned Bellamy and Keythe Farley.

In August, the company returned from an international tour of Robbins’s new production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which played to sold-out houses in China and Italy. In the fall, the Gang took the show to Nashville, and did their first prison project work outside of California at a correctional facility nearby. Then they traveled to Brazil.

I sat down with the soft-spoken, 6-foot-5-inch Robbins in early September, on a day he wasn’t filming for HBO or rehearsing with the company. A California native who grew up in New York’s Greenwich Village, Robbins says he’s pleased to once again call California home. For our meeting, he chose Hal’s Bar on Abbot Kinney in Venice.

JOSEPH EASTBURN: How did the Midsummer tour go?

TIM ROBBINS: Amazing. Last summer we did a workshop production. We captured the theatricality, the movement, the passion. The thing that was missing for me was a deeper understanding of the language. So we did a two-week workshop on just language. Great plays have so many different layers to them.

How did audiences in China and Italy respond to Shakespearean comedy, particularly through the lens of the Gang style?

I have to say, our style works around the world. Because it’s inclusive of the audience, it acknowledges that they’re there—it plays emotion directly through their eyes to the other actor onstage. It played very well in China. There were supertitles above the stage, but I was watching the audience, and after a while they started just watching the play and giving over to it. In the first scene of Midsummer, we learn that there’s been an arranged marriage. They still have arranged marriages in China. So what we came to understand was that this was a modern play for them—young people in their early-to-late 20s saw that first scene and said, “This is a play about my life!” And how do you solve the problem of a loveless, arranged marriage? You go to the forest. There, you find magical beings and spells and drugs.

For the readers that don’t know, what is the “style,” and what is its relationship to commedia dell’arte?

I took a workshop in 1984 with a man named Georges Bigot from the Théâtre du Soleil. He was the lead actor in the Shakespeares they were touring with, and had just performed at the Olympic Arts Festival here in Los Angeles. We had an amazing amount of theatre companies roll through here during the Olympics, from El Teatro Campesino to Piccolo Teatro di Milano to Théâtre du Soleil—from all over the world, great theatre. But the hit of the festival was Théâtre du Soleil. So Georges was doing a workshop on commedia dell’arte with masks, and I took it, along with three other members of the Actors’ Gang. I was a working actor at this point—and I could not get on the stage. He kept throwing me off. I would make entrances and he’d throw me off. I was freaking out a little bit…but I finally realized what he was talking about.

He said you weren’t ready?

He said I wasn’t in the emotion. What he was demanding of us was total commitment to an emotion and an image. He had cobbled together some costumes. And we would dress and put on makeup and wear masks, so that the whole image of the character was apparent from the very start. This created a very high bar for what was going to be on the stage: absolute truth. The combination of the state of the emotion, the urgency and image you created—upon entrance—immediately told a story without words.

So I took this method. It’s the work of Ariane Mnouchkine. She runs the Théâtre du Soleil in Paris and has since the early ’60s—a groundbreaking theatre artist, who carried on the tradition of Lecoq, but in a different way. There are ways to teach the commedia that would have nothing to do with emotion, states and urgency and telling a story. That was their take. And we took it into our own sensibility.

I saw your theatre-in-the-park adaptation of Midsummer for families; I marveled at how well the style translates to comedy, and particularly for small children.

One of the things Georges would talk about was: There’s a trap in theatre where we can fall into a disrespect, even a disinterest, in the audience. It manifests sometimes when you’re in a long run and you have a bad night and you say the audience sucks. For us, the audience never sucks. It’s us who has a bad night. Never blame it on the audience. They deserve everything. They deserve all of you. That is what we do.

Looking back at the plays the Gang has done over the years, many have political themes. Why do you think that’s so rare in the theatre?

Well, those are hard plays to do, number one. We should always be pushing the boundaries of issues that make society uncomfortable. We were more interested in European theatre and the approach taken by some of those dramatists—Brecht and Ionesco and the Surrealists and German Expressionists. We did Woyzeck, The Good Woman of Setzuan, Peer Gynt. We were interested in that kind of world in disorder that came out of the playwrights writing after World War I and in World War II. How do you deal with this new reality that comes out of human behavior? And what is human behavior in the midst of this reality?

For me, many of those plays were certainly relevant to our lives in the ’80s and ’90s. But those kinds of plays are hard to do, and are not the particular favorite of theatre critics.

Can you talk about how your politics have evolved as we approach another election cycle?

The last two years I’ve been advocating for the kind of theatre that is transformative to the heart and soul. That’s what we need now. I mean, we’re still touring 1984, the Orwell play, and that still works in the places we’re touring it to. But as far as developing new pieces, maybe it’s just this stage of life, or maybe it’s the fact we’re in such a fucked economy, and the crises in the world are so extreme—maybe the most radical act is to have audiences walk into a theatre and transport themselves into joy.

Over the years, you’ve worn many hats: actor, screenwriter, film director, playwright, stage director, artistic director and producer. What were you searching for, and have you found it?

It’s better now than it’s ever been. I have more clarity, more focus, and I’m doing exactly what I want to do. And I’m blessed to be in that position. I’ve always had the ability to say no. And now, it’s saying no to temptations that take you away from the reason you started it all in the first place—why I wanted to tell stories, why I wanted to be an actor.

Earlier in my career, when we started the Actors’ Gang, I was guest-starring in episodics, earning pretty decent money, but before movies. I would tell my agents, I’m going to do a play, and I’m not going to audition for anything for three or four months. And it drove them bat-shit. But what it ended up doing was giving me a laboratory to learn more—where I’m consistently reminded that I haven’t figured it out yet. I think that’s an important thing. Every time I approach a new piece, I haven’t figured it out. I have the opportunity with people who are trained in the same way, to find a new truth to a piece of theatre.

How has the Gang changed since it moved from Hollywood to Culver City?

Culver City had a bigger need for facilitating outreach programs. So we went with it. All our education programs and our prison project got started as volunteer programs. We thought, if we wait for funding to happen, it’ll never happen. But if we do it—it might happen. And it did happen. We got a grant from Sony to do our afterschool program, and some in-school diversion programs in the Culver City school system. Two years later we got a grant to do summer performances in the park that were free. Throughout our history, in Hollywood and Culver City, we’ve always had free performances. You have to make it available, so it’s not this elite thing that you can only go to when you have, you know, 200 dollars.

So the idea was: The only way the theatre can be a sustainable art form is if you find and sustain a new audience. Where is the youth that’s going to buoy up your theatre to support it? It’s interesting, when you go to Europe, waiting on line for a play in Paris, you see these kids with nose-rings and punk-rock hair going to see Molière. Why? Because when they were children, they were taken to the Comédie-Française by their schools.

With the budget cuts that have stopped arts programs in the L.A. public schools, the Actors’ Gang conducts free in-school, after school, and summer programs.

That’s one of the reasons we did it. Because, in the late ’90s and early part of 2000, they had made those cuts. Unconscionable cuts. It’s not forward-thinking.

There have been similar cuts for arts programs in California prisons, but the Gang has kept working inside prisons. Why? Or, I should ask, how?

Well, Sabra Williams, who played Titania in Midsummer, created the prison project about eight years ago. We had an artist facilitator. We didn’t receive funding from the state at the time, but we had someone at the prison who would facilitate our getting in and getting the prisoners to us. About four or five years ago, they cut all funding for any arts programs in California prisons. So, we said to the warden, we’ll come, just get us in the door—we don’t need anything from you but a key in, and a way out. And he said yeah. So we continued it even though we no longer had a facilitator.

And then we started expanding it. We had been doing a lot of outreach to politicians, to people in the state correctional system, and after a couple of years of trying, we finally got the head of the Department of Corrections—his name is Jeffrey Beard—to come to one of our final presentations. And then we went to meet with him a couple of weeks later. And he said to us, “What you’re doing may be arts rehabilitation, but it’s also behavioral therapy; you’re doing cognitive therapy here. And I totally support it.” That’s because he saw how it works.

It’s not that we’re doing theatre in prisons—it’s that we’re doing this particular discipline. Because it’s so physical, because it’s so demanding, it’s something that prisoners respond to. And from the start, one of the things I said to Sabra is that we’re not psychologists. We don’t go in there and talk about their problems. We go in there and give them characters.

You don’t know what crimes they’ve committed.

We don’t want to know. If you boil it down, what happens, in essence, happens because they’re playing characters. They’re able to express emotions they’ve never expressed in their life. If you have another actor expressing anger, we tell them it’s much more interesting to choose one of the other three emotions: happiness, sadness, fear. And what happens is that they start doing scenes where they’re responding to anger with fear, or with sadness, which is true empathy, or with happiness, which diffuses the situation.

You’ve heard that your guys have zero recidivism, whereas the California statistic is 65 percent.

Anecdotally, yes, we know of no new re-offenders. We were working in one section of the prison, in Norco, Calif. And we said to our group of guys, “Look, we have to go work in another part of the prison for a while, we’ll see you in about five or six months.” About four months later, we get a message from the prison that, in our absence, they had gotten permission from the prison to use the room one night a week. Two of the inmates we had trained had formed a theatre company, had trained 40 new guys and had written a play that they wanted us to come and see.

We got a call from the attorney general. So Sabra and I went to Washington, D.C., to the Justice Department, and the person we met with said, “I think we can do something with this on a nationwide basis. We need the authority to make a federal program out of it. We need the absolute hard data.” So we’re working on getting hard data. If the recidivism rate is anywhere near 20 percent, that’s compelling when the nationwide average is in the upper 60 percent. I don’t know if we can make that happen—but it’s on the radar.

Recently, the Los Angeles Times theatre critic Charles McNulty wrote a piece saying that L.A. theatres should “look north,” using the example of the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, with its cycle of U.S. history plays. He was contrasting that with the bland programming at some of the big institutional theatres in L.A., instead praising some smaller companies like the Fountain. He said what the theatre needs is visionary leaders.

Did he mention us?

No.

This is part of the problem. It’s a mystery to me, honestly. We get rave reviews around the globe. We get houses in China sold out every night: 1,600 seats in one venue, 600 in the other. We sold out all the shows in the Spoleto Festival with a 500-seat house. We got great reviews in Italy, Greece, Spain, South America and Australia. The Times is a mystery. It would be nice to have the support of our leading paper. We do have the support of the L.A. audiences that come and see us. And that’s what’s important. They keep coming. We sold out Midsummer all summer long. They know it’s good. They respond to it. They tell their friends. I think sometimes critics can get in a vacuum and not really reflect what audiences are responding to. I certainly know that when I go to see plays that have gotten rave reviews, I’m often flabbergasted. I really think it boils down to taste.

What are the Gang’s plans for the rest of the year?

We’re in workshop right now on a couple of different pieces. We’re developing a piece for Italy. We’re going to Milan to do an original piece in June.

A new piece?

Yes. And the piece we’re developing for January will probably go to China in September. While we were there, we were invited back to their larger theatre. It might be a Molière—I’m a big believer in not getting too far ahead of ourselves. We used to do seasons. And that sometimes cheats you out of opportunities that present themselves, like if a certain director becomes available and wants to do a play. So we like to be able to respond to the moment that we’re in, and develop pieces out of that. But we do know that in the summer of 2016, we’re going back to the Spoleto Festival, where we can have the venue that we used before—but there are two other venues in the complex, and they said they want to create what they call “Actors’ Gang village.”

It sounds like the Actors’ Gang is an international company.

It is. (Pause.) It is. Next summer we’re going to be in Lyon, France, in one of those old Roman theatres to do Midsummer.

If you look back on the scope of your theatre career, how would you describe it, and where are you headed now?

I had a moment in Italy—one of those crystalline moments, after a great performance and a standing ovation: I thought, I’m exactly where I want to be. There was also meeting Robert Wilson and seeing his direction of Peter Pan with the Berliner Ensemble, the Ensemble coming to see Midsummer and loving it, us going to see their show, loving it; all of us having a party at this villa, bonding, getting drunk, telling stories. It was one of those moments where I realized—this is what I’ve always wanted in my life. I wanted to be a theatre director when I went to UCLA. The acting was, you know—I got lucky. But I always kept coming back to the Actors’ Gang. That’s what I’ve been doing for 20 or 30 years, traveling the world with the company. I find it incredibly fulfilling. I remember thinking, in Spoleto: This is the dream, right here.

Joseph Eastburn has written plays, screenplays, short stories and nonfiction. His first novel was published by William Morrow and Co.