It’s not merely a concert setting for a song cycle, and it’s not a piece of full-on musical theatre, either. The theatrical staging of Gabriel Kahane’s knotty concept album The Ambassador lives somewhere in between. And this is perfectly fitting for Kahane, a man of many talents who’s been courted by virtually all corners of the performing arts world.

He’s best known as a musician who synthesizes influences from classical, pop and art songs into work that’s often dense with contemporary concern. (His breakout composition in 2006 was a series of solo-piano settings of text culled from Craigslist—it quickly entered the new-music repertory and has been performed by Audra McDonald at Lincoln Center.) But Kahane was first trained in the theatre, and he says that’s where he picked up the knack for storytelling that is evident in his songs.

“At the end of the day, people want to know what story they’re being told, and whether they’re going to be affected emotionally or not,” Kahane says, on the phone from his home in Brooklyn. “And while the music I write may be somewhat sophisticated by pop-music standards, I’m still trying to communicate pretty direct stories.”

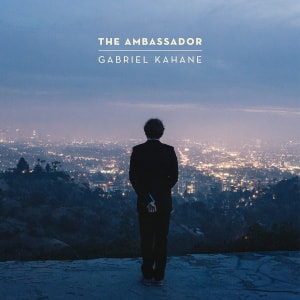

So far, the world knows The Ambassador as a thoughtful set of sophisticated chamber pop songs, examining the city of Los Angeles through the architecture of 10 of its buildings. The album, which is the composer’s major-label debut (on Sony Masterworks), earned him a round of critical huzzahs and instantly became the key album in his pop portfolio. But it was actually born as a commission by Brooklyn Academy of Music, which presents the stage incarnation Dec. 10–13 as part of this year’s Next Wave Festival. John Tiffany, who won a Tony in 2012 for his staging of Once, directs.

Kahane knew he wanted to write about L.A., but hadn’t hit upon a unifying conceit until Tiffany, very early in the process, suggested the device of anchoring each song to a specific street address. “I was having all these various ideas about how the piece might be organized, involving time travel, and Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure, and architecture, and all of this heady stuff,” Kahane says with a grin in his voice, before Tiffany chimed in with the “succinct brilliance” of a seasoned stage director. “The mark of a great director,” Kahane adds admiringly, “is being able to synthesize and distill an artist’s teeming, disorganized creativity.”

With the concept in mind, Kahane and Tiffany had two days together in L.A. They spent part of the time on a driving tour of buildings that would be referenced in the songs. “It’s still not a place I’d want to live,” Tiffany says of the city, “but seeing it through a songwriter’s eyes, it becomes more complex and rich as an idea. He’s opened my own eyes, in some ways.”

Los Angeles may not seem the most natural subject for this musician, who has spent the last several years closely identified with musical movements flourishing in Brooklyn and Manhattan. But Kahane was born in Venice Beach, and his family eventually ended up in Northern California when he was two. His parents—Jeffrey, a pianist and conductor, and Martha, a psychologist—sent him to the arts-minded Santa Rosa High School, where he studied acting in a program he remembers as serious and rigorous, with a bit of a slant against musical theatre. That negative impression toward musicals would linger.

Creative, restless and unsure of just what he wanted to do with himself, the clearly precocious youth dropped out of high school before graduating, but picked up a GED and spent a year studying jazz piano at the New England Conservatory in Boston. He found his way from there to Brown University, where he acted in more shows and sat on the governing board of the student theatre program.

Kahane’s classmate and friend Thomas Beatty, now a film director, enlisted him to co-write a musical, under duress. The result, called Straight Man, won the musical-theatre award at the Kennedy Center American College Theater Festival in 2002. Kahane laughs and makes self-deprecating quips when the topic of that piece comes up, but he notes that it set him on the creative (and career) path he’s followed since.

“The process really enamored me of having put something down on the page, whereas as an actor I had that famous post-partum depression everyone talks about” after a show closes, he says. “Writing that musical was what led me to become a songwriter in the first place.”

After college, Kahane moved to New York and got his first jobs in the world of theatre. He hooked up with Alex Timbers’s company Les Freres Corbusier and was musical director for a series of Timbers-directed shows, including Hell House and A Very Merry Unauthorized Children’s Scientology Pageant in New York, and the initial L.A.-area tryout of Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson.

He was happy to get the jobs, of course, but says now he still wasn’t harboring any grand ambitions about the work he could do in musical theatre. When he accepted playwright Tommy Smith’s proposal to write songs for an alt-country musical (Caravan Man) that was due to workshop at Williamstown Theatre Festival in 2007, he was motivated in part by the prospect of earning some extra dollars by subletting his Brooklyn apartment while the festival put him up in the Berkshires.

It’s fair to say his interest in the possibilities of musical theatre intensified the following year, when he landed a commission from the Public Theater, with help from some arts patrons who had taken to his music. With playwright Seth Bockley, another friend from Brown, Kahane wrote the music and lyrics for February House, a musical based on Sherill Tippins’s book about a communal home in Brooklyn Heights that for a time counted among its residents a cluster of creative personages, including W.H. Auden, Benjamin Britten and Carson McCullers. (See AT May/June ’12.)

Bockley remembers nights spent crashing in Kahane’s cramped Park Slope apartment, sleeping under his host’s baby grand piano and getting a musical wake-up call when it was time to resume their work in the morning. The playwright, who has since adapted short stories by George Saunders and a Roberto Bolaño novel, says that Kahane’s penchant for synthesizing various influences and inspirations was evident.

“We’re both voracious readers and consumers of culture, and both of us see ourselves, I think, as artists standing on the shoulders of others and building off what others have done,” Bockley reasons, “with respect and really an obsession with what has come before, in every art form.”

Sylviane Gold, for one, was positively rhapsodic in her New York Times review of the show’s takeoff run at New Haven’s Long Wharf Theatre in 2012, writing that the songs “herald the arrival of a major talent on the musical-theatre scene.” She added that it seemed clear Kahane “will be one of the artists nudging musical theatre in new directions in the 21st century.” Not bad for an artist who hadn’t been quite sure he was all that interested in musicals.

“I really fell in love with the form, and I started to understand not only what a monumental undertaking it is to try to birth a musical but also how much technique is involved in trying to make a piece work,” Kahane says. By the time February House closed, he’d already been the subject of a profile in the New York Times Magazine. In short order, he had his concert debut at Carnegie Hall, leading a program of his own work, and released an album of the February House songs as well as a solo debut record featuring his melodic, literate chamber pop. He kept booking gigs in the realms of classical and new music, writing for progressive chamber groups like yMusic and the Kronos Quartet as well as the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

By the time BAM and Sony came calling, he had turned his thematic interests westward.

By the time BAM and Sony came calling, he had turned his thematic interests westward.

“I was born there, but when I returned to L.A. more recently, in my mid-to-late twenties, I was increasingly overwhelmed by the sense I had of an ache that sits beneath the surface of what a lot of people consider to be a somewhat superficial city,” he explains. “There are these two cities, the mythological L.A. and then the vulnerable, physical city.”

As he speaks, Kahane is readying for two days of rehearsal with the seven musicians who will join him as the sole performers in the stage incarnation of The Ambassador. They are slated to conduct a working residency and one performance at Carolina Performing Arts in Chapel Hill, before four shows at BAM.

The production will include all the songs from the album, plus a handful more (and one well-chosen cover), knit together by text and sound culled from sources that inspired the work—books like Mike Davis’s The Ecology of Fear, whose chapter about fires in L.A. obliquely inspired “Slumlord Crocodile (115 E. 3rd St.),” sung from the perspective of a lovesick arsonist. References from Bruce Willis to Frank Lloyd Wright dot the album, in the voices of characters both real and imagined.

The songs of The Ambassador look at the city from disparate angles, amounting to a mosaic that’s beautiful and grotesque. A song cued by the Bradbury Building, which features prominently in the film Blade Runner, includes lines from that film. “Empire Liquor Mart (9127 S. Figueroa St.)” is sung from the perspective of Latasha Harlins, a 15-year-old girl shot and killed at that location in 1992. Kahane aimed not to be overly didactic, using his intellectual inquiries as seeds for stories and characters. But on the wordy “Villains (4616 Dundee Dr.),” he lets his inner pedant loose, explicitly echoing lines of inquiry from Thom Andersen’s film Los Angeles Plays Itself. (First line of the song: “Why do villains always live in houses built by Modernist masters?”)

Set designer Christine Jones (Spring Awakening, American Idiot) remembers Kahane covering a table with books and other source material when the creative team got together for a workshop in March. This display of research led to the concept for the set, an impressionistic panorama of the city that suggests a physical manifestation of the songwriter’s thought process. Towers of books stand in for downtown skyscrapers; the Hollywood Hills are fashioned from piles of screenplays. Cassette tapes and other cultural detritus litter the scene. “I think the idea is that it’s almost as if he is in his living room, staying up late writing songs and having ideas,” Jones says. “Gabe is sort of this possessed musician who is building up L.A. around him and exploring different thoughts.”

Possessed? Perhaps. Just as his career as a pop musician is taking off, Kahane is working on another commission from the Public, as well as a collaboration with Annie Baker, who won the Pulitzer this year for The Flick. He says the rewards of his work in different art forms are different, but similarly pleasing.

“I feel a particular thrill being onstage and singing my music, having that communion with an audience,” he allows, “but there’s also the magic of a dark theatre during tech, and being one of 100 or even 200 people working to make this ship go. That is also deeply moving, and satisfying.”

BAM executive producer Joseph Melillo brought Kahane into the fold after catching a few of his concerts around New York City. He sounds particularly optimistic about the collaboration. “Fundamentally it is about his storytelling—I think he’s a unique storyteller. This is a man with extraordinary observatory powers,” Melillo says. “We’re just seeing the beginning of the ways this talent is going to mature and evolve. I’m happy to be on the trail.”

Jeremy D. Goodwin is an independent journalist based in the Berkshires. He contributes reguluarly to the Boston Globe and New England Public Radio.