Sometimes you find yourself climbing a hill because you’ve been promised theatre at the top. One recent afternoon I was in Edinburgh, Scotland, for that city’s renowned Fringe Festival, hurrying uphill holding onto directions, trying to figure out if the flowers on the side of the path were the yellow ones meant to signal my next turn. Eventually I managed to find my way to the location of American artist Greg Wohead’s theatre piece, Hurtling.

After it was over, I bounded back downhill, brain whirling with thoughts of memory, time and human connection. Everything around me seemed new in light of the emotional journey I’d had in Hurtling. Then I stopped. I realized I was lost—that I’d never been down this path before. Hurtling had so overtaken me that my sense of direction was completely gone.

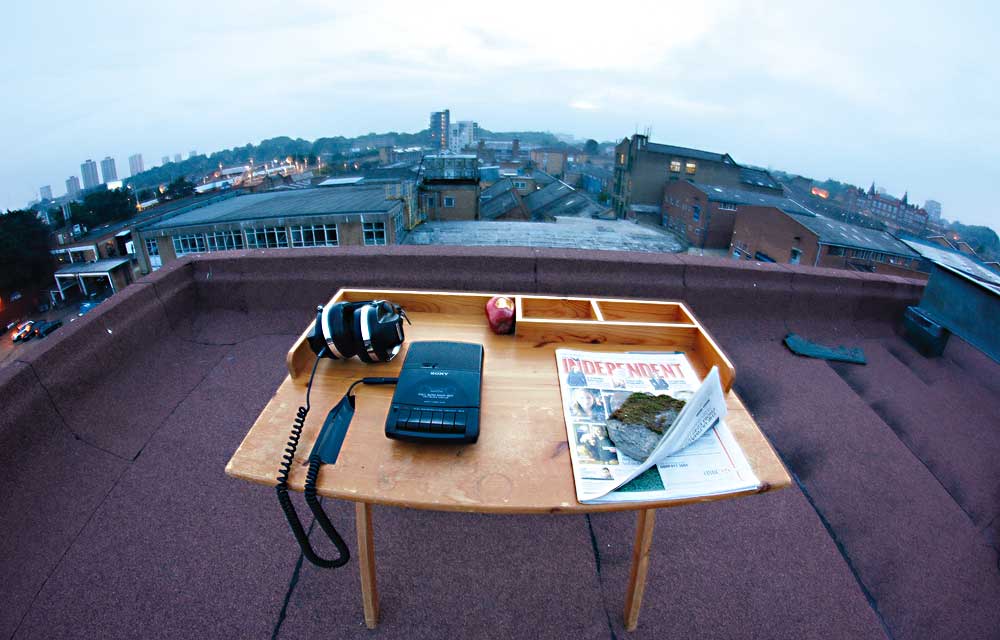

Although Wohead’s piece is based on a deceptively simple concept, it blooms into something penetrating and intimate. As the performance’s sole live participant, I sat at a desk on a grassy hillside overlooking the blue waters of the Firth of Forth with a tape player and a pair of headphones on. I pressed play and Wohead spoke to me from the recording. His voice traveled from the past; he had sat in the same chair, looked out at the same view, earlier that morning. We breathed together. I heard him chomp an apple, which now sat on the desk before me, half-eaten. Yellowjackets were flying around the apple; Wohead’s bite mark had oxidized. Decay had begun in that short while, and this apple marked time before my eyes in a simple but beautiful way. As he whispered in my ear, all I could think about was time—my past, my present, this indelible moment.

I can’t say much more, because Hurtling works best if you discover it for yourself. And you should, if it comes your way.

I’ve been coming to EdFringe for the past three years. This time, armed with a raincoat, some outrageously colorful European comfort shoes and a local bus pass, I crisscrossed the historic Scottish town over five-and-a-half days to visit 13 venues, see 29 shows, and eat so many Tunnock’s Teacakes I felt sick. Begun in 1947 as an unofficial offshoot of the Edinburgh International Festival, the Fringe is now the largest arts festival in the world. There were more than 3,000 shows—ranging from comedy to cabaret to music to plays to indescribable, genre-defying performance art—on the official program this year, and many additional ones happening unofficially around town.

Despite the decidedly British flavor of many of the Fringe offerings, there’s always a strong American contingent as well. And through one-on-one performance, audience participation or just good old-fashioned punk-rock antics, American artists at the Fringe this year seemed intent on obliterating the fourth wall, demanding an exciting new level of direct engagement.

American artist Brian Lobel, for instance, kindly asked his audience if they wanted a hug. I fell in love with Lobel’s work when I saw his Purge at Forest Fringe (an artist-curated offshoot of EdFringe, celebrating its eighth year in Edinburgh) in 2013. Originally, Purge was a 5-day, 25-hour performance in which Lobel spent one minute talking about each of his 1,300-plus Facebook friends; after each précis the audience would vote whether to keep or delete the friend. Now when Lobel performs Purge, we find out what happened in the aftermath of those original votes. As Lobel reflected on his relationships, our social-media lives and the early death of a young ex-boyfriend, I could not help but turn those reflections on myself and my relationships—both IRL and otherwise.

Lobel has a knack for creating a welcoming space for gentle introspection and for shifting, ever so slightly, the way you think about your world. So it was no surprise that for this year’s show—titled You Have to Forgive Me, You Have to Forgive Me, You Have to Forgive Me, after a pivotal quote from “Sex and the City”—he invited audience members to climb into bed with him for a chat and a clinch. Audience members were required to fill out a 92-question survey made up of questions Carrie Bradshaw asked during the show’s six seasons; these answers were shared with Brian, who then joined each individual audience member in bed to cuddle, talk and watch a “Sex and the City” episode.

“What I got excited about with regard to live performance versus the DVD box set is that box sets don’t change, but we always change every time we watch them,” Lobel ventured. “With this show, a lot of people have cried; a lot of people have talked about their horrible relationships; a lot of people have talked about how their relationship will never feel as good as a fictional one, which has been a really emotional common theme.”

Of course, creating a work that involves sharing your most intimate experiences pushes theatre to the edge of comfort for many people. Lobel figures that some 80 percent of audiences would not want to participate in a show like this, starting with the probing questionnaire (e.g., “Is it better to fake it than to be alone?”)—but for that remaining, adventurous 20 percent, Lobel is making theatre where the vitality comes from candid, personal interactions.

Other artists at Fringe were looking to generate similarly candid, up-close interactions—minus the comfort zone. A number of shows, in fact, set out to agitate, thrusting audiences into unsettling scenarios with little room for reflection or release.

Brooklyn-based director Rachel Chavkin joined forces with UK theatre artist Chris Thorpe to create the one-man show Confirmation, based on Thorpe’s attempt to engage in “honorable discussion” with men who hold political views as far from his own as he can imagine, including a neo-Nazi and a Holocaust denier. A charismatic performer, Thorpe speaks in the voice of a man named Glen, whom he calls a “nuanced, complicated racist.” In one scene, audience members pose questions to Thorpe, who responds as Glen, turning the spectators into participants in the inquiry, with no choice but to face “Glen” and his way of thinking. The play is probing and unnerving, especially when you are called upon to challenge or question long-held beliefs.

I was similarly tied in knots watching Greg Wohead’s second piece at the Forest Fringe, The Ted Bundy Project, about the fabled serial killer. Wohead, who’s been based in the UK since 2005, grew up in Texas, trained originally as an actor, and got a taste of devised work after spending a summer at the Hangar Theater in Ithaca, N.Y., studying with directors Chavkin, Lear deBessonet, Steve Fried and Shana Cooper. “The four of them were amazing,” Wohead recalls, “and what they were interested in really influenced us.”

After creating a number of autobiographical works that were often described by audiences as “really lovely,” Wohead moved on to harder-edged material. In The Ted Bundy Project, he is intent on creating tension and anxiety; luring the audience in with his affable nature (not unlike the purported charm of the real Bundy), Wohead then taunts the audience with violent imagery, a confessional tape made by Bundy himself and a ritualistic presentation of evidence from one of Bundy’s victims. Attracted by curiosity, we’re then repulsed by our own engagement. Wohead says he’s interested in taking the kind of dark excitement from which people might derive pleasure “in a private space” and bringing that energy into “a communal space.” With the lights up on the audience, there is nowhere to hide; we are forced to look at ourselves individually and as a group gathered to watch, to confront our roles as gawkers and consumers of violent media. Wohead’s approach makes us all culpable—himself included.

On the night I saw The Ted Bundy Project, though, something unexpected happened: During a scene in which an audience member is called onstage to help out, the selected spectator hesitated, and for a long moment it seemed as though the show might not go on; eventually he acquiesced. Perhaps because the audience member, Paul Soileau, was a performer himself (as I later learned), he was less trusting in this theatrical situation.

Afterwards, Soileau told me he felt “gullible” going onstage and standing where Wohead told him to, sensing he was being treated “like the victim.” It was when Wohead handed him a prop that the tenor of the moment changed and Soileau felt that he was able to assume “the power position.”

Soileau knows a little something about danger and power onstage. I later encountered him at a late-night show, The Christeene Machine, starring as Christeene, a genderqueer singer-dancer-den-mother-of-destruction, blowing up the concept of cabaret. In an almost indescribable maelstrom, Christeene arrives onstage carried in the arms of her back-up dancers, removes from her anus a butt plug decorated with balloons, and proceeds to spray the audience from various bodily orifices. Christeene and her dancers, with their shredded clothes, filth-smeared bodies and lyrically explosive, infectiously danceable tunes (titles include “Fix My Dick” and “Tears from My Pussy”), create a world of contradicting extremes. While the show is raucous and dangerous, Christeene herself turns out to be eager, vulnerable and understanding. With a message about connecting to the child you were and listening to the “ponies” inside your belly, an unexpected gentleness emerges.

As Soileau explained to me, the point of the show is to have the audience “find their true character—get out of the character you play on the street every day. Forget that. That’s your gender, your job, your relationships, your character.” Christeene proves the beguiling spirit-guide to help you do just that.

This year’s EdFringe offered no hiding in the dark with proscenium boundaries to protect you. The Americans at the Fringe reached out beyond the confines of the stage to ask us to think, share or connect.

Nicole Serratore is a theatre lover based in New York. She blogs at Mildly Bitter’s Musings and talks all things theatre on the Maxamoo podcast. She also posted a web-only list of her 10 favorite things at EdFringe.