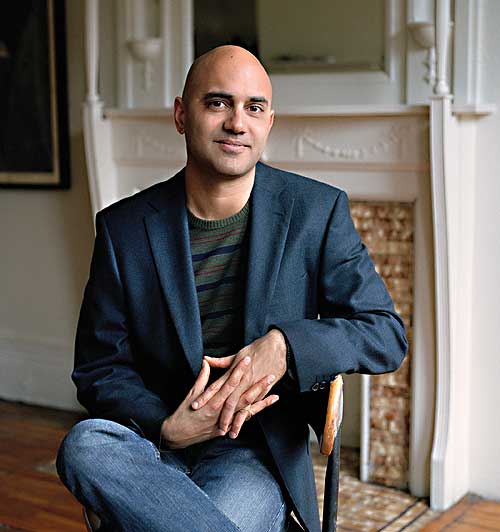

(In its July/August 2013 issue, American Theatre published the full-length playscript of Disgraced by Ayad Akhtar. In honor of the show’s current run on Broadway, we are reposting our interview with the playwright.)

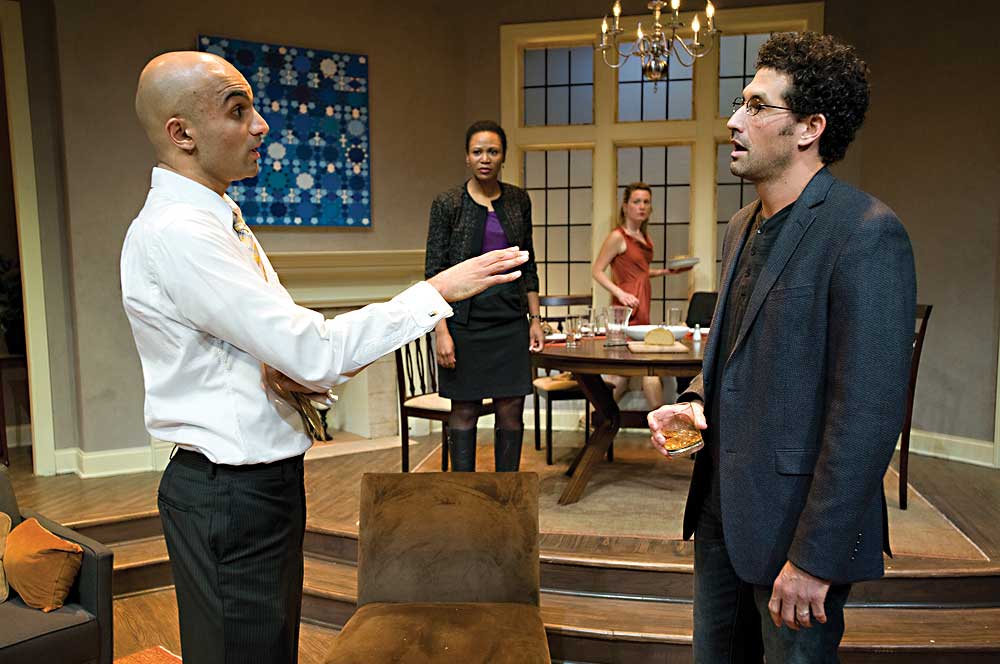

Disgraced builds to a fateful dinner party, at which an interracial couple—a South Asian lawyer who has rejected his Muslim faith and his wife, a Caucasian artist who takes her inspiration from Islamic art—play host to another couple, a Jewish art curator and his African-American wife, also a lawyer.

The stakes are high for everyone present, both personally and politically—and the evening ends in violence. Disgraced premiered at American Theater Company in Chicago in early 2012 before moving to Lincoln Center Theater later that year. It took the 2013 Pulitzer Prize for drama. Below is a conversation between Akhtar and Madani Younis, who directed the UK premiere of Disgraced at the Bush Theatre in London in 2013.

MADANI YOUNIS: It’s your last day in London. Talk to me a little about your observations about a British audience confronting Disgraced here at the Bush Theatre.

AYAD AKHTAR: It seems like in both countries there’s an equal level of intensity in terms of engagement, but it almost feels like the British audience is giddy with excitement at the end of this play. It’s not that they don’t go through the troughs and the emotional shattering, but there’s this kind of ebullience. In New York there was a similar intensity, but it was not enthusiasm. It was a kind of quiet, a deep, alive sadness, something much more recognizable as a response to tragedy.

What have your conversations been like with the audience members at the end of the show?

There have been two kinds of reactions. One is people coming up to me to acknowledge they’ve had a meaningful and emotional experience. And then some folks come up to me and ask point-blank what it is I’m trying to say.

You re-crafted Scene 4 for this production. Why?

One of the issues I was continually having with Disgraced over the last couple of years was the transition out of Scene 3 into Scene 4. After the intensity of the events in the third scene, the audience was still very much with the act of violence. And we would start the fourth scene in a very tangential and narrative way; we were not clear what the connection was to what we’d just seen. So there was this kind of long speed bump, during which I felt audience members shifting in their seats. It seemed to me if there were a way to bridge that more viscerally, we could get right to the meat of that fourth scene without that hiccup. Your questions and suggestions opened up the possibility of Abe coming in at the end of the third scene and Emily and Abe showing up at the beginning of the fourth. This solved it for me.

Let us for a moment talk about the violence in the play that is perpetrated by Amir upon his wife Emily. What does that moment mean?

Well, I want it to mean many different things. It’s obviously playing into certain Islamophobic tropes. I want the audience to be so fully humanly identified with a protagonist who acts out in an understandable but tragically horrifying way, that even if you put that Islamophobic text on top of it, it doesn’t change his humanity.

That’s the subtlest level. But there are so many other levels, too. There is the psychological dimension, there’s the gender relationship, the gendered religious relationship, the gendered modern relationship, and, of course, on another level there’s also the act of political violence—that is to say, a colored male subject acting out on a white paramour as an act of political violence. In that respect it is drawing on a tradition of representation I was very consciously in relationship to, at least in my own head. Shakespeare and V.S. Naipaul and William Faulkner. I wanted that act of violence to be in dialogue with similar acts of violence defined by that lineage.

One of the things that’s problematic to a lot of people is that some readings of the play seem to undermine other readings. And so the question becomes, well, what is the reading of this play? My contention is that your reading of this play tells you a lot about yourself. And I’m reminded about that wonderful thing that Rainer Werner Fassbinder, the New Wave German filmmaker, once said, about how he wished to create a revolution not on the screen but in the audience.

A hypothetical question, but one I feel duty-bound to ask: What would the play become if it did not have the violence we witness between Amir and Emily? That scene could occur with Amir walking out and leaving Emily standing alone in that space. What does that version of the play look like?

Well, I think that play is much more concordant with contemporary dramaturgical practice. But that’s not the play I wanted to write. I wanted to engage the audience in a way that was much more fundamental. I feel drawing on melodrama, potboiler, romantic thriller, situation comedy—all of those things offer the audience a way to relate to the play not as an object of art but as an experience. I don’t want them to feel the intrusion of the author between them and the experience that they’re having.

In the past 48 hours we have been inundated with some across-the-board strong reviews from our newspapers. We’re seeing right-wing papers referring to this moment in the play through a very particular lens toward Islam, and we’re seeing the left-wing papers referring to this in a far gentler, accessible sense. What has that made you think?

It makes perfect sense to me that people would gravitate to whatever reading is going to help them. But ultimately that doesn’t really matter, because there’s another kind of space that’s been opened up. I want to give you an example. There was a Scottish-born Muslim woman of Pakistani descent who came to see the show a couple of nights ago who wrote me an e-mail saying, “It’s been two days since I’ve seen it, and I’m still deeply troubled. I find myself walking through the streets in a different kind of depression than I’ve experienced before, wondering what people are really thinking and really is there hope for the future?” On one level we can say, wow, that was a real downer. Or on another level we could say she has dropped to another state of reflection about where the world is. That kind of clear-eyed approach to reality is something for which I’m hoping the play can be a portal.

Look, at the end of the day, art’s capacity to change the world is profoundly limited. But what it can do is change the way we see things individually. I aspired to accomplish with this structure a kind of shattering of the audience, after which they have to find some way to put themselves back together.

Let me ask you, then, in response to what you’ve just said: Is the play hopeful or hopeless, from your perspective as the playwright?

I’m not sure that it’s either. What it is, I hope, is an access point to a state of presence.

For the characters, is there hope at the end of the play?

I would repeat: I believe that in Amir’s case, as well as Emily’s case, and in his own way Abe as well—the events of the play have provided access to the present, to things as they are. The only way we can change the world is by recognizing what it is that we are now.

As you know, I myself am Muslim; I’m Sufi, I’m British born, this country is home for me. I can imagine young Muslims who encounter this play are surprised by the character of Amir. Not necessarily by what he says, because we are confronted by that shit every day. But the perversion, almost, of the play is the fact that this man who looks like me, a brown man, is also spouting this hate that for so many years post-9/11, and post-7/7 for us, has been sort of the preserve of our white brothers and sisters. What are the thoughts that you leave young Muslims with after this play?

It’s a problematic, complex, deeply troubling play. I’m not going to avoid that. What I would say is the concussive impact of its very economical 90 minutes belies a complexity of design on a metaphorical level. The play begins with a Western consciousness representing a Muslim subject. The play ends with the Muslim subject observing the fruits of that representation. In between the two points lies a journey, and that journey has to do with the ways in which we Muslims are still beholden on an ontological level to the ways in which the West is seeing us. And what the play might be suggesting is we are still stuck there. And that being stuck there, this is what we are living in and with, and these are our options. So the play ends with Amir finally confronting that image.

I do believe personally that the Muslim world has got to fully account for the image the West has of it and move on. To the extent we continue to try to define ourselves by saying, “We are not what you say about us,” we’re still allowing the West to have the defining position in the discourse.

Madani Younis has been the artistic director of the Bush Theatre in London since January 2012. Previously he was the artistic director at Freedom Studios in Bradford, England.