Daniel Burnham, the architect and planner who created the “White City” of Chicago’s 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, famously said, “Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men’s blood.”

The fair—whose stucco-clad buildings lit by thousands of streetlights earned it the luminous nickname—was Chicago’s way of showing the world that it had bounced back from the Great Fire of 1871, which tore a three-mile swath through the heart of the burgeoning metropolis and left around 300 dead and 100,000 homeless. Ever since then, the “phoenix from the ashes” metaphor has been Chicago’s central cultural narrative.

So it’s perhaps fitting that Redmoon Theater’s ambitious Great Chicago Fire Festival, slated this Oct. 4 (four days before the 143rd anniversary of the conflagration), itself arose out of disappointment and failure—namely, the October 2009 failure of then mayor Richard M. Daley to win the bid for the 2016 Summer Olympics.

Jim Lasko, executive artistic director of the 24-year-old company, says that the idea behind what has become the largest undertaking in Redmoon history was a response to his “fighting for local artists’ participation in whatever that thing was going to look like”—by which he meant the opening ceremonies of the hoped-for Summer Games.

Well, that thing didn’t happen; Rio de Janeiro won the bid, and the rest is Olympics history.

But Lasko—who had been talking about plans for the Olympic opening ceremonies with Lois Weisberg, longtime commissioner of cultural affairs for the city (Weisberg retired in 2011)—and his company didn’t want to let those plans die with the bid. So Redmoon decided to revisit the idea of creating a spectacle beyond any of the outdoor site-specific work they had been creating in recent years.

Spectacle has been Redmoon’s watchword from the beginning—its earliest productions, under original founders Blair Thomas and Lauri Macklin, featured al fresco settings, often incorporating puppetry, à la Bread and Puppet Theater. The first Redmoon show this reporter saw was a 1990 adaptation of Moby-Dick staged on the shores of Lake Michigan, featuring enormous puppet heads on poles. (Jeffrey Dorchen, one of the founders of Chicago’s revered fringe troupe Theater Oobleck, co-wrote the adaptation with Thomas; Mickle Maher, another Oobleck stalwart, has also frequently collaborated with Redmoon.)

Lasko and producing artistic director Frank Maugeri—who have shared top leadership responsibilities for the company since 2010—moved Redmoon further into the realm of creating events that combined large-scale outdoor temporary installation art with a variety of performance styles. Lasko was awarded a 2013 Loeb Fellowship from Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design to further study ways to use public spaces as settings for urban art experiences.

According to Lasko, another impetus for the festival was Redmoon’s desire to reconnect with the spirit of one of the company’s most successful and long-running past public events—the annual All Hallows’ Eve celebrations in Chicago’s northwest-side Logan Square neighborhood, which generated ever-increasing crowds from 1995 to 2002.

“Those were immensely popular, and we loved making them,” says Lasko. “But the burden of production was too great for us at that time. We just didn’t have the capacity as a young organization to keep up with the exponential growth.” He added that Redmoon “had the entire production and budgetary burden” of what had become a large-scale civic endeavor that eventually drew as many as 10,000 spectators.

OVER THE PAST SEVERAL YEARS, Redmoon’s work has included more traditional, if still expansive, indoor shows—this past April’s interactive “choose your own adventure” piece Bellboys, Bears and Baggage, very loosely based on The Winter’s Tale, spread out over the troupe’s vast 57,000-square-foot industrial space in Chicago’s Pilsen neighborhood. The outdoor spectacles, by contrast, often take over city parks with a variety of visual-art installations and performance events (some reflecting an overall narrative structure and others in the ambulatory pick-and-choose mode). There are also smaller-scale workshops and community programming, some of it presented under Redmoon’s “Urban Interventions” rubric, which brings various contraptions (a fire organ and a drum cart among them) to augment performances in public parks and parades.

“We began doing the neighborhood-based work as a separate function from the large-scale outdoor spectacles,” Lasko explains. The Great Chicago Fire Festival, he feels, finally gives Redmoon a way to meld those threads into one extravagant whole.

It was in numerous meetings with Michelle Boone, the current commissioner of the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events, as well as with an array of other governmental, neighborhood and cultural organizations, that the central ideas and images of the festival began to take shape.

Lasko considered the Chicago River development when he pitched to Boone, and he was eager to ground the festival in the 2012 Chicago Cultural Plan that the city had adopted. What he proposed, Lasko says, was “something that could only happen here—something that is such a unique manifestation of who we are that it would catch fire” (pun apparently not intended).

Commissioner Boone was receptive. “What was appealing to me is that right from the beginning we wanted to set this up as a new model for how the city does new festivals,” she noted. “It was an opportunity for a true partnership with a cultural institution to incubate a concept and give it enough legs so it could have a life beyond the city.” The result: Lasko says that the city is providing about $350,000 of the estimated overall $2-million budget for the Great Chicago Fire Festival, with the rest coming from private and corporate donations.

Additionally, notes Boone, “We’re really the liaison for Redmoon in navigating the many city agencies and other public agencies that have to be on board with presenting something of this scale. So, for example, for the Chicago River, we really have to work with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. That’s probably a new agency for a cultural institution [to partner with].”

In coming up with the final ideas for the event, Lasko notes, “We asked ourselves, ‘What are the big things that need to be true for this thing to work?’ One was that it needed to reflect our geography—thus the river. It needs to reflect our culture—thus the neighborhood aspect of it. And it needs to reflect our history.”

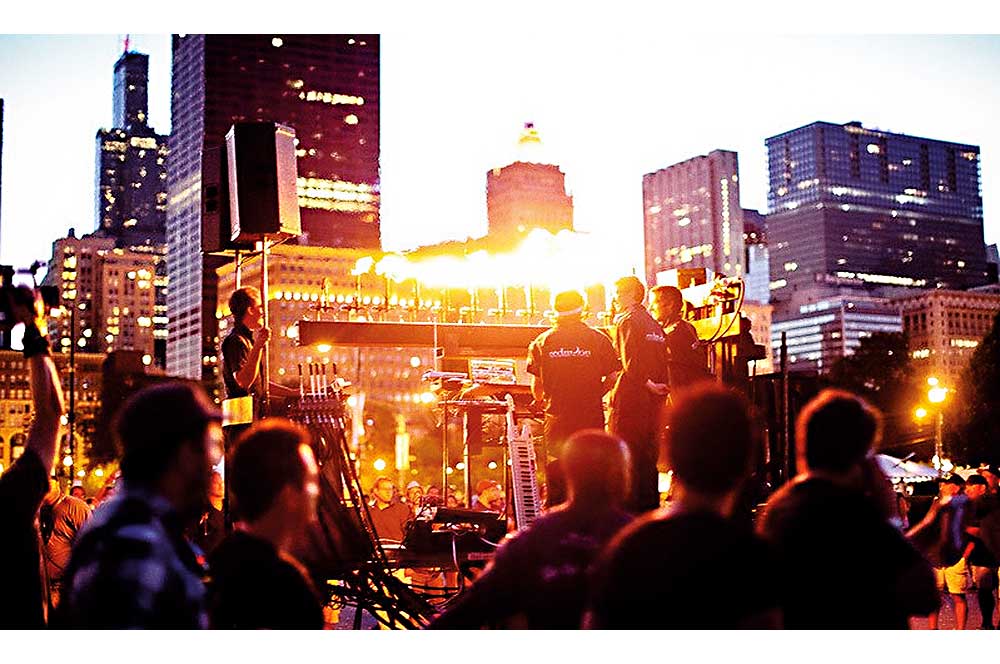

What will audiences see as they line the banks of the Chicago River’s main branch between the State Street and Columbus Drive bridges on Oct. 4? They’ll experience a sort of urban ritual that makes use of iconography and imagery redolent of the 1871 disaster, but that ultimately becomes a celebration of the city’s current residents.

Three floating platforms on moored pontoons in the river will serve as the centerpiece for the event. One is filled with what Lasko calls “references to pre-1871 architecture” as well as emblems of people who lost their lives in the Great Fire. As of August, the plan was for glassblowers at Chicago’s Ignite Glass Studios to create sculptures honoring the victims. The second platform “is a demonstration of the heroic acts of our first responders,” says Lasko—performers dressed as firefighters will actually douse the flames of a burning house on the platform. The third will reference the great architectural renaissance in Chicago, the birthplace of the skyscraper, after the fire. Additionally, Lasko says, the riverfront itself will have “a community stage that will be occupied by community-based talent.”

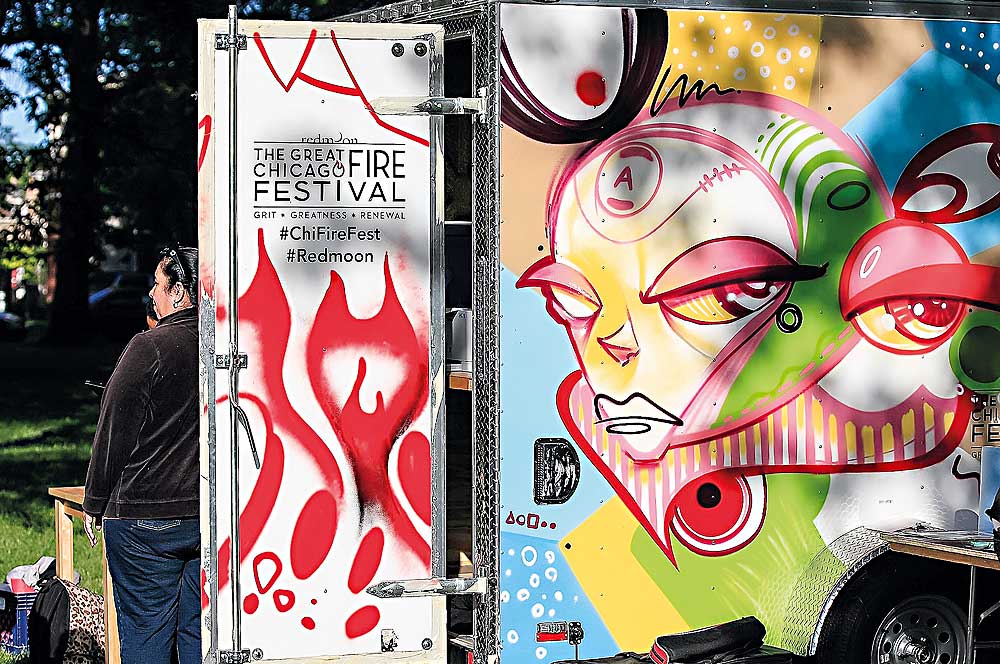

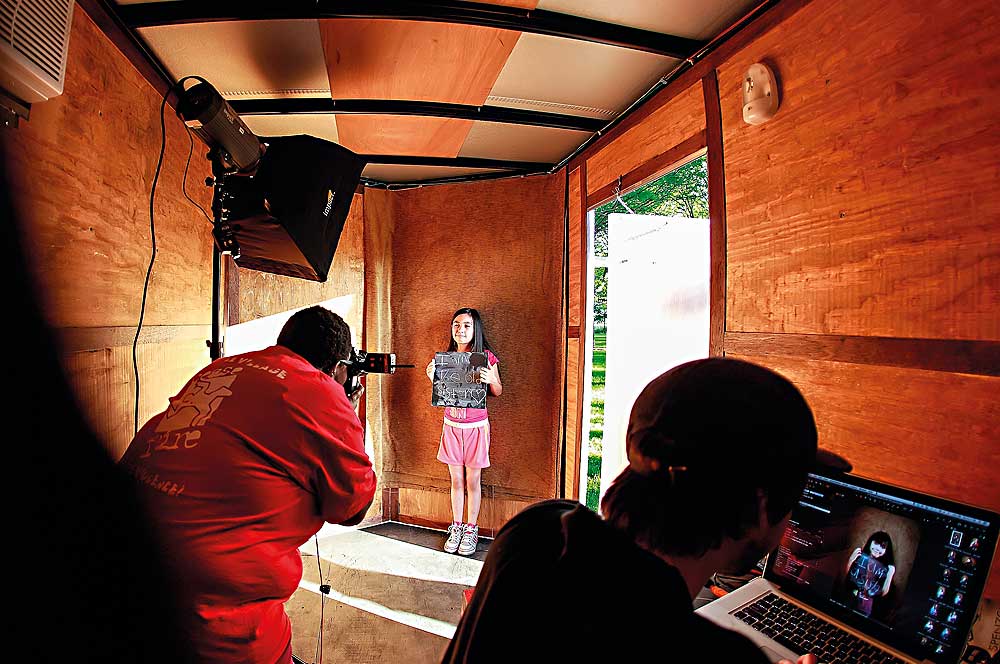

In a larger sense, much of the real work of the festival has already taken place in the communities involved. Outside Redmoon’s massive Pilsen workshop, where teams of fabricators were welding and sawing on a recent July afternoon, Lasko pointed out a traveling photo booth, designed by well-known Chicago photographer Sandro Miller.

Constructed within an old horse trailer, the booth has spent the summer traveling to at least 15 neighborhood festivals, where community residents fill out a slate shaped like the flame logo of the festival. On one side, they write a response to the prompt “I overcome.” On the other, they write a response to “I celebrate.” They then have their photos taken holding their proclamation. Miller conducted workshops with Redmoon interns who traveled with the “mobile photo factory,” as the company calls it.

While everyone who goes through the photo factory leaves with either a button or a sticker of their image, Lasko says when “people who write especially interesting or provocative or idiosyncratic things, we go and do further video interviews with them.” At the festival itself, banner versions of some of the photographs will decorate the riverside, and the finale will include a large-scale projection of photo-factory images as well as “the people who helped us make the show,” says Lasko.

Lasko and his team also decided that it was important to partner with existing organizations in traditionally underserved neighborhoods to create ongoing relationships between Redmoon and residents. “We’re going to the more neglected neighborhoods that are now being identified with gun violence, frankly,” he says, “to collect stories that celebrate the grit and renewal and resilience of those neighborhoods and the people in them.”

On Aug. 5, Redmoon took part in the “National Night Out” program, run locally through the Chicago Police Department, in Bronzeville’s Ellis Park. A historic hub of African-American culture in the city’s South Side, the neighborhood has also seen more than its share of gun-crime tragedies. At one point, three mothers whose children had been murdered led the crowd in chanting, “Put the guns down!” and decried the “no-snitch policy,” or code of silence, which leads residents to refuse to identify shooters to the police and makes it harder for perpetrators to be arrested. “I don’t call them gangbangers,” one mother said. “I call them terrorists.”

That grim note was leavened by the overall celebratory atmosphere in the park. In addition to the photo factory, Redmoon brought their “cyclone grill,” a rotating series of elevated grilling stations, manned by local chefs and powered by bicycles. One station includes a spot for a DJ, who, at Ellis Park, introduced local teen performance poets and dancers. Tables with information from a variety of civic and social-work organizations filled the lawn while a long line formed for both the free food and the photo booth. One young woman’s slate for the latter bore the twin legends, “I overcome negativity. I celebrate being alive today.”

Community collaboration is key for creative teams working on the festival. Matt Binns, who has collaborated with Redmoon several times, is a sculptor, fabricator, designer, installation artist and all-around provocateur who is a creative force (along with sculptor/woodworker Erik Newman) behind “Guerilla Flotilla” [sic]. The flotilla is an extravaganza of floating sculptures that periodically sail down the Chicago River in, as a 2007 feature on Chicago’s WBEZ public radio station put it, “an illegal parade of unlicensed boats.”

Binns and Newman are going legal with their contribution to the Great Chicago Fire Festival, which Binns describes as “a steam-powered paddleboat with smoke and clanging and hissing and all that goes with a 19th-century steamboat. It has to be completely maneuverable, it has to float, and it has to meet with Coast Guard standards of safety.” During the festival, three smaller steamboats will be dispatched from the larger boat and set the three central platforms on fire.

In addition to the design and engineering challenges presented by the steamboats, Binns is also coordinating “everything that goes on in the water,” an effort that requires cooperation from “the Army Corps of Engineers, the city, the fire department.” Binns and Lasko point out that, though the structures on the platforms are designed to be burned and then extinguished (itself a highly delicate engineering feat), the platforms themselves can be reused in future incarnations of the Great Chicago Fire Festival. “Right now, it’s the ‘dark satanic mills’ kind of boat—blackness and noise,” Binns notes. “Next year it could be Thomas the Tank Engine.”

Whether the festival can become a sustainable annual event remains to be seen, of course. But in making “no little plans” this year, Redmoon has laid the groundwork in a way that would make Daniel Burnham, the fashioner of 1893’s “White City,” proud. “We’re not celebrating the fire that destroyed the city and killed hundreds,” Lasko insists. “Instead, we’re celebrating the spirit that brought the city out of the fire.”

Kerry Reid writes about Chicago theatre and is a regular contributor to this magazine.