SAN FRANCISCO: “I have never stopped considering changing the title of this play,” confesses Laural Meade, author of Harry Thaw Hates Everybody. “It doesn’t sound in period. I hear it and I think I’m going to see some kind of crime drama.”

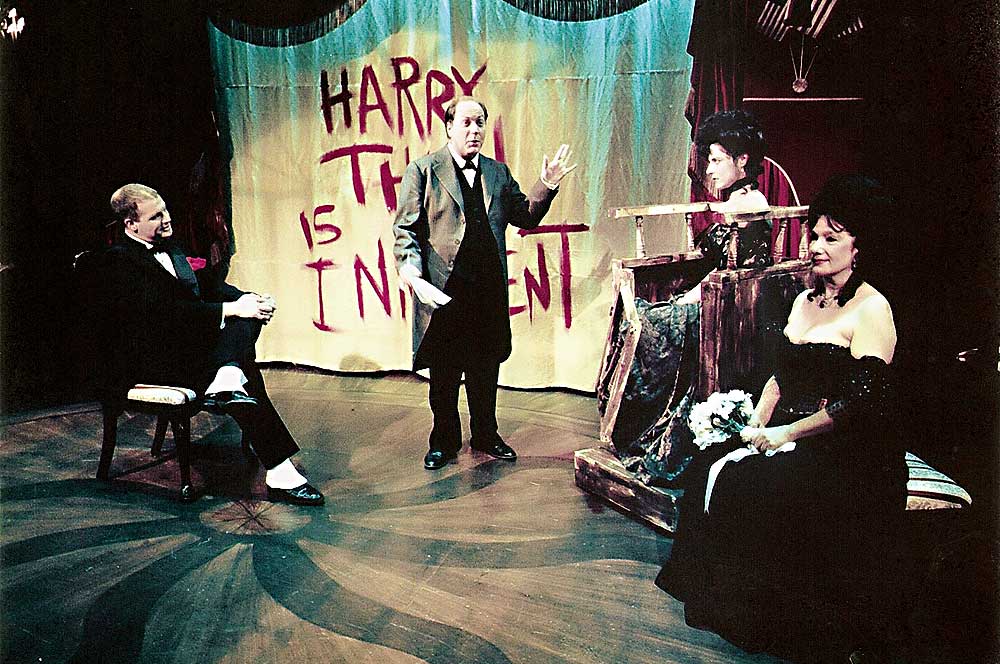

Of course, Meade’s mercurial play—which had an award-bedecked 1999 premiere at the Los Angeles Theatre Center and will be remounted at San Francisco’s Shotgun Players Oct. 15–Nov. 16—is a crime drama of sorts, recounting the 1906 slaying of eminent New York architect Stanford White by Thaw, an unhinged tycoon jealous of White’s relationship with his wife, teen starlet Evelyn Nesbit.

The bratty anachronism of the play’s title serves a purpose—it gives notice that Meade’s approach will not be as narratively straightforward as was E.L. Doctorow’s novel Ragtime (and the musical based on it), in which the Thaw/Nesbit/White triangle was one strand in a broad American tapestry.

Inspired by the period, and fueled by her own irreverent sensibility (her previous play was Leopold and Loeb: A Goddamn Laff Riot), Meade says she “started to write a little melodrama,” then realized she could organize the play by character and style, giving each player an “act” in which to tell his or her side of the story. White’s is a winking vaudeville revue, Thaw’s is a “courtroom farce,” Nesbit’s is a disorienting “avant-garde collage.”

This mold-breaking form is one reason for the long gap between the play’s debut and this revival. Meade, who directed the L.A. premiere, struggled to translate her multisensory staging to the page. Eventually, though, she got it published by Samuel French, which is how Shotgun—on the prowl for underproduced plays by women, according to artistic director Patrick Dooley—found it.

Director M. Graham Smith says his production, inspired by the boxing bells Meade includes to mark scene breaks, will “feel very much like an athletic competition.” Another reference point: an image of escape artist Harry Houdini hanging from a crane, which gave Smith the idea of “hanging a beautiful beaux-arts chandelier from an oily derrick, to highlight the extravagance of the era.”

This points to another, less happy reason the play’s jarring title may be apropos: The gaping inequality of the Gilded Age, as well as themes of rape and public gun violence, make Harry Thaw feel more timely than ever, says Meade. “Though I treat it with a great deal of entertainment, with high kicks, I’m trying to look at why we do what we do.”