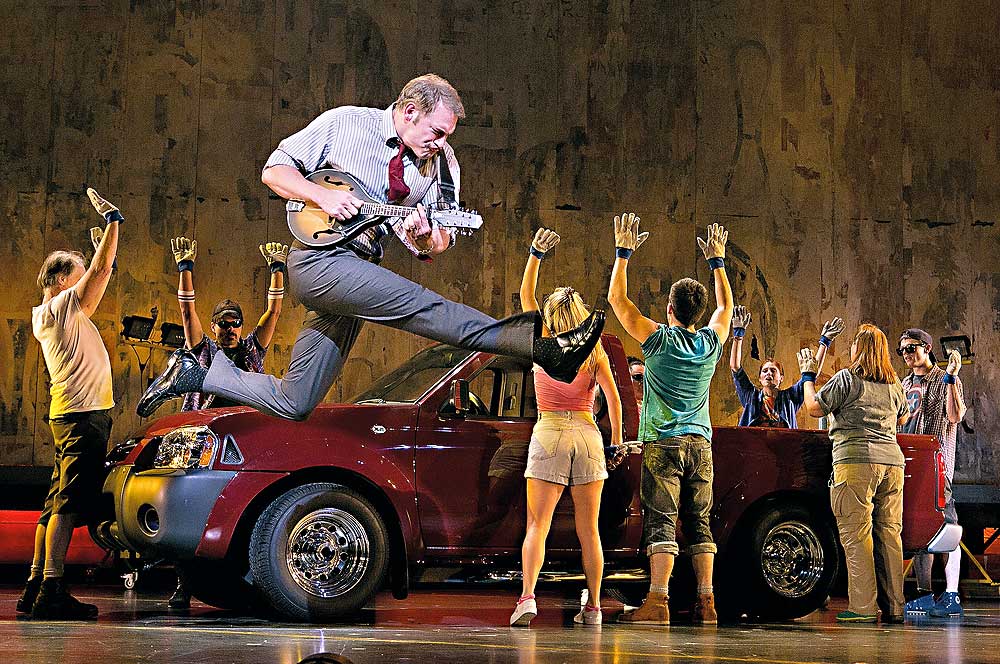

Amanda Green can’t keep the energy out of her voice. She’s trying to explain to me what it was like moment to moment to witness the June 12 opening of Hands on a Hardbody, a musical adaptation of the documentary she co-wrote with Pulitzer-winning playwright Doug Wright and Phish guitarist Trey Anastasio, in its Texas premiere. The musical—in which several Texas locals compete to win a truck by seeing who can endure the longest touching it—had a tryout at California’s La Jolla Playhouse (AT May/June ’12), followed by a disappointingly brief Broadway run and a robust regional afterlife.

The premiere Green was anticipating took place at Houston’s TUTS Underground, an offshoot of Theatre Under the Stars. That company presents popular hits like We Will Rock You and The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas, while TUTS Underground, its second stage, specializes in edgier work, like the cult musical Reefer Madness, mounted in a space the company website dubs an “intimate 500-seat theatre.”

Since Wright is originally from Texas, and both the musical and the documentary film on which it is based take place there, the creative team was excited about the show’s first Texas staging. As Wright puts it via e-mail, the show has “a special piece in my heart, because it allowed me to put some of my frustrations with the notorious state to rest—its antediluvian politics and ferociously ‘old time’ religion—and focus instead on the innate hospitality, tenacity and good-humored spirit of so many of its people. I was deeply invested in its Texas premiere.”

So was the staff at Samuel French, who went so far as to help TUTS rent the titular truck from the Broadway production.

According to Wright, Green “was incredibly enthusiastic and eager to see the show on the resident-theatre circuit, in part because its run on Broadway was so short. She flew down to Houston on her own dime.” She also committed to pre-show press availability in Houston and attending a cast function after the performance, along with her husband and the Broadway executive producer Jennifer Costello. Unable to attend themselves, Wright and Anastasio told her to fill them in on how it went.

They got a phone call at intermission—a call that would lead, perhaps inexorably, to the show being shut down less than a week later.

The first sign that something was off came at the very top of the show, when, in place of Anastasio’s opening instrumental guitar solo, an actor announced to the audience the names of the various characters. Next, Green says she noticed that various lines had been reassigned, seemingly at random. Then the opening number skipped from the song’s middle to its end.

She laughs about it now, but Green says that at the time, “I was disoriented. And then a second song started playing—and I remembered having a debate among the creative team about that song and whether it should be second or not, and us deciding that it shouldn’t be.” When the character of Janice started delivering lines from the second act in the middle of the first, Green began to wonder if she was misremembering her own show.

She wasn’t the only one to notice the changes. At first, her husband tried to calm her down before he too realized what was happening. Meanwhile, Costello began furiously scribbling down everything that was going wrong in her program. “It was surreal,” Green says. “I was incredulous. I couldn’t believe it was happening and I had to watch it unfold. And then at the end of the act, they sang, ‘If I Had This Truck’ instead of ‘Hunt with the Big Dogs,’” the song that was supposed to end the act “on a huge moment of conflict.”

As the show features contestants who are eliminated serially over the course of the evening, changing the song order was no small matter; it changed the actual plot of the show. Characters who were supposed to be in Act 2 no longer were. In the second act, Green recalls, “Songs started to happen that had the wrong number of vocal parts because of the reordering—one song had 10 vocal parts in it, and it was sung by four people. By the time ‘Hunt with the Big Dogs’ happened, there were very few people left onstage, so lines were randomly given out. The very religious character told the leading man she was going to ‘kick his ass.’ It didn’t make any sense.”

What made even less sense, she says, was the conversation she had with Bruce Lumpkin, the show’s director and TUTS’s artistic director, after the show. “I tried to avoid him—I just wanted to go to the hotel,” Green admits. But Lumpkin “accosted” her, she says, and reportedly told her, “Okay, I know you’re pissed off, but you have to admit it’s better.”

“No. I don’t think it’s better,” she replied.

“Well, you know,” he said, “it’s just modular changes. I put them in last night. If you don’t like them, just say ‘no’ and we can switch them back.”

“Okay,” Green said. “No.”

Lumpkin’s contention that the changes were not a big deal is at the heart of this story. To Green, reordering the show’s songs means changing its plot. To Lumpkin, who wouldn’t comment for this story but gave an interview to arts administrator and writer Howard Sherman on his website in June, reordering doesn’t constitute a real change. No dialogue was altered, he pointed out—although who spoke it was—and no lyrics were rewritten. He told Sherman: “There was no new vision for the show. It was just a matter of the order of the songs.” Sherman additionally wrote that Lumpkin claimed the changes were made “over three days only after rehearsals had begun.”

In some sense, you might say that Lumpkin simply treated the show the way a film director would in an editing room. But the norms in theatre around the director/writer relationship are quite different from the director/writer relationship in Hollywood—or the editor/writer relationship in mainstream publishing, for that matter. In theatre, not only can you not make changes to a writer’s text; it’s generally considered out of line for directors to even give prescriptive notes on a new play. In publishing, editors and agents consider it their job to give prescriptive notes, though they stop short of actually changing the text. In film, writers don’t even own the screenplays with their names on them and have little or no control as to what happens to them in an editing room. (For an illuminating example of this dynamic, watch the Steven Soderbergh film The Limey with the commentary track on, and listen as screenwriter Lem Dobbs kvetches at Soderbergh throughout about the changes the latter made to the former’s screenplay on set and in the editing room.)

Still, norms are norms, and theatres sign licenses assuring they will perform the play as is. Furthermore, there is some dispute about Lumpkin’s claim that he changed the show at the last minute. Green claims she has been informed that actors were given a CD of the show with the songs reordered and a revised script at the first rehearsal, and that efforts to restore the show to its original version in the days after the opening were not successful.

Green’s claims are backed up by a cast member of the show who spoke under condition of anonymity. “We only learned one show,” the performer said. “The show that we did initially is the show that it was from the first day of rehearsal. My personal assumption was that we were doing a different version of the show—my feeling was that we never had any reason to question anything.”

Were any additional changes made during the course of rehearsal? Cast members say small changes did happen: “We would come in and a song would be a little bit different, or a scene.” In his interview with Sherman, Lumpkin mentions that there were some discrepancies between the script the team was given and that of the Broadway show, a contention that representatives of Samuel French, which handles the rights for the show, dispute.

The interviewed performer says he remains conflicted about the changes they made. “Given the licensing agreement, that may not have been the best decision,” the actor says of the changes, “but every decision [the director] made served the piece. In my opinion, the new version that we put up onstage served the piece and the story and the characters better than the version on Broadway. It’s hard to be in a position where you have to choose between art and legal stuff. I’m not defending anybody, but I was in the show. We served the story. Everything that we figured out—all the organic stuff that happened in the room, the cuts, the changes that happened as a result of our work—served the piece. And we were very proud of what we did.”

Green begs to differ. “It was not good,” she tells me. For Green, and for representatives from Samuel French, Lumpkin’s statements are disingenuous. As French executive director Bruce Lazarus puts it, “The most off-putting thing about it was not how brazen these changes were and that Bruce Lumpkin didn’t ask for permission, but that he was so unapologetic about having made the changes. He never copped to the fact that he was doing something that was unauthorized, not in the author’s interest, and without permission. He took the position that we were making a big deal over nothing.”

Lazarus first learned about the changes when Green contacted him Friday night. By Saturday morning, he and French’s director of licensing development, Brad Lohrenz, had contacted TUTS and received assurances from TUTS CEO John C. Breckenridge that the issues would be looked into. As they discovered the scope of the problem, Lazarus contacted Sherman to interest in him in writing about it, and informed the Dramatists Guild.

To all involved, this seemed a particularly egregious case. As far as Wright knows, for example, no one has ever changed his work without his permission. “Ironically,” he wrote me, “I tend to be pretty generous about directorial approaches to my text when I’m approached about them. Once I’ve seen my plays rendered faithfully in original premiere productions, I often welcome new interpretations. I Am My Own Wife is a one-man show, but I’ve authorized productions using as many as 22 actors. So I’m not a staunch purist.” French’s Lohrenz also tells me that his company receives requests for script changes all the time, “usually having to do with community decency standards,” and that they always bring these requests to writers.

What’s more, the times when Sam French has caught unauthorized changes—easier, they tell me, in the age of the Google alert—the process of fixing the situation usually goes more smoothly. Lohrenz holds up as a counter-example the publisher’s recent dealings with Asolo Repertory Theatre of Florida’s production of Brian Friel’s Philadelphia, Here I Come!, directed by Frank Galati. In that case, reviews of the show tipped Lohrenz off that changes had been made; two characters went unmentioned, including the protagonist’s mother, and the intermission seemed to have been cut.

In that case, Lohrenz says, Asolo Rep “went super-fast into let’s-get-this-fixed mode.” Artistic director Michael Edwards immediately accepted blame for the changes, closed the show, flew Galati back in to put the show back together, visited Sam French’s offices in New York to discuss what had happened, and flew Lohrenz to Sarasota to see the show and their other current productions. “So,” Lohrenz quips, “any theatre in Florida that wants to make changes to a show is fine by me, so long as they fly me down.”

According to the performer I spoke with, “Those few days after Amanda saw the show are a kind of a blur.” By Sunday, the cast learned they would be rehearsing the show to put it back together, “but I say that lightly, because there was no ‘back’ for us. We learned it one way. We had to learn a completely new show in three days.” From Tuesday, June 17, the cast began rehearsing the show as originally written. “We were rehearsing on the set with the worklights on. It was very surreal—like walking into ‘The Twilight Zone.’” They performed the reconstructed show on Thursday, June 19, after just three days of rehearsals. How did they get through it? “We had cue cards, like a set list of the show, in the truck.”

Before the performance on the 19th, which would turn out to be the show’s last, the Dramatists Guild issued a sternly worded letter to Lumpkin, detailing the accusations against him. Its startling bill of particulars included that he “treated the rehearsal process like a workshop of a new musical”; that altered scripts and reordered CDs were handed out to the cast on the first day of rehearsal; that additional music was written and added to the score; that the songs were reordered and their parts reassigned; that the story was “radically altered”; and, perhaps most damningly, that Lumpkin did not fully restore the show once its creators protested, and even then did it “begrudgingly and unapologetically, with a history of having done it before (moving the act break into the middle of a song in In the Heights) and with apparent plans to do it again (as it has been reported to us about your upcoming production of Best Little Whorehouse in Texas).”

By this point, Sam French and the creators of Hands on a Hardbody had reached the limits of their patience. In their minds, their initial PR offensive—done in part to pressure TUTS into restoring the show—hadn’t worked. According to Green, “They didn’t offer to have us come back to see it. We didn’t trust them. It felt like a charade.” The interviewed performer insists that the intent was to perform the full, restored version of the show, but that with only three days of rehearsal and two different iterations of the same material in their heads, the cast made mistakes and occasionally reverted. The creators didn’t wait to see the results: They decided to shut down the show. French sent a cease-and-desist letter, and Hands on a Hardbody closed.

Everyone involved is quick to stress that shutting the show down was an action of last resort—“absolutely a very tough decision to make,” Green insists. “The point of writing a show is to have people see it. Despite everything, audiences were responding to the characters and songs. Also, actors, lighting people, musicians, they’re out of jobs!”

Wright adds, “For all of our careful work on a musical that we hold very dear, Trey, Amanda and I aren’t victims. We were well served by our licensing company and our Guild. The unfortunate ones are the actors, designers and theatre staff who contributed their time and talent to a misbegotten, illegal production. And Houston audiences, who were robbed of the opportunity to see a legitimate version of the piece.”

“Closing something down is not our first option or choice,” Lohrenz concurs. “We always try to get it fixed. It’s not good to close a show. People lose work. It’s a very unfortunate thing.”

Since the cease-and-desist letter, things seem to have calmed down. Sam French continues licensing shows to TUTS, including the aforementioned The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas, which ran in June. And Hardbody continues to truck its way around the regional circuit. There will soon be productions in Colorado, in Ohio and, once again, in Texas, at Theatre Three in Dallas (where, Wright says he “used to act in juvenile roles”).

But French is leaving nothing to chance in the future: It is instituting a new policy whereby directors must sign a statement saying they’ve read the theatre’s license for the show they’ll be directing. “We’re not asking directors to be liable under a contract,” Lazarus explains. “We just want the theatre to take responsibility for informing directors of the rules.”

One question remains, however: Why did Lumpkin make the changes in the first place? And, having made them, why did he invite the creators to see the show? In the absence of official comment from Lumpkin or TUTS, that question will remain unanswered.

As for the French team, Lazarus and Lohrenz both confess to not having a clue why people make changes to shows without permission. Lazarus says, jokingly, “There are three drives of mankind: The drive for food. The drive for sex. And the drive to rewrite somebody else’s play.”

New York City–based Isaac Butler writes regularly about the theatre.