Costume designer Ana Kuzmanic came to theatre sideways, through dual loves of art and fashion. The Chicago-based designer, who over the past 10 years has progressed from storefront theatres and shoestring budgets to working regularly at major companies like the Goodman, Steppenwolf, Chicago Shakespeare and Lookingglass, didn’t have the stage on her radar when she began sketching stick-figure renderings as a kid growing up in the former Yugoslavia.

Costume designer Ana Kuzmanic came to theatre sideways, through dual loves of art and fashion. The Chicago-based designer, who over the past 10 years has progressed from storefront theatres and shoestring budgets to working regularly at major companies like the Goodman, Steppenwolf, Chicago Shakespeare and Lookingglass, didn’t have the stage on her radar when she began sketching stick-figure renderings as a kid growing up in the former Yugoslavia.

“I was interested in drawing. There’s just that artistic streak, I guess, that I got from my mom,” Kuzmanic says. “I remember that even when I was very little I would draw these figures: triangular people and square people and oval people and asymmetric people.”

In her teens, this predilection evolved into an interest in representations of the human figure in art—which led to a revelation about fashion: “Even though we all have two legs, two arms, pretty much a similar shape, at a particular time, this is beautiful, and then at a later time, this is beautiful. There’s the human desire for altering the body and augmenting it and reducing it,” she explains. “Then I realized in high school that there is a profession of costume design. So I guess my way in was not that I was in the theatre one time and saw something onstage and fell in love with it—it was more through just starting with the human, and then going to the text.”

Kuzmanic is tall, willowy and modest in speech. On the occasion of our interview, she had just returned from a family vacation to her small, sunny studio on the sixth floor of a 1920s building in downtown Evanston, Ill., a few blocks north of Chicago’s city limits and near the campus of Northwestern University, where she earned tenure last year as an assistant professor of costume design.

Northwestern is what brought Kuzmanic to the Midwest in 2001, to pursue an MFA. She had completed her undergraduate degree at the Faculty of Applied Arts in Belgrade, where she could double-major in costume and fashion design. “At the beginning, I was more interested in fashion, because of how arbitrary it is,” she avows. (In fact, she designed a fashion line for several years before coming to the States.) “And I remember as I started working more in theatre, I began to like theatre more for exactly the opposite reason: Nothing’s arbitrary. You have to be so specific.”

Specificity is what makes Goodman Theatre artistic director Robert Falls a Kuzmanic admirer—and a frequent collaborator.

“She does what other designers are supposed to do, but she somehow does it better, with greater range and greater scope,” Falls says. “She has this remarkable eye and this incredible visual memory and imagination.”

It was at Northwestern that Kuzmanic first met Falls, who was teaching there at the time. “I was teaching a class on American realism, and we looked at the plays of O’Neill and Williams and Miller in particular,” Falls recalls. “Ana just did this absolutely remarkable work from the get-go. There was something very, very special about it that set her off from all the other students. There was her talent, and the fact that she was European, and that she had come from a fashion design background, initially—she had more life experience than a lot of the other graduate students.”

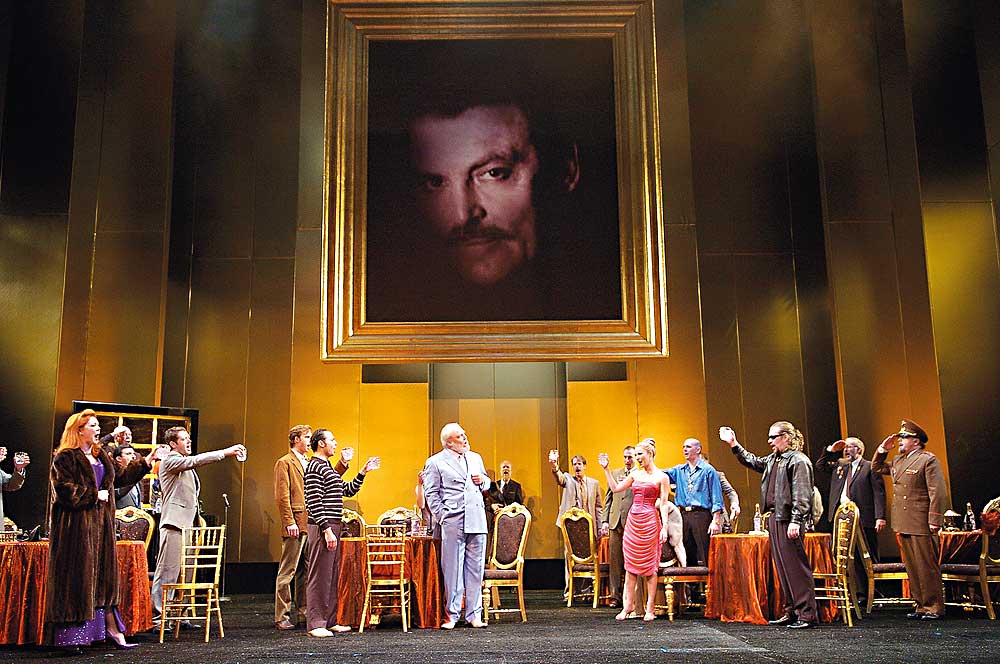

Falls first approached Kuzmanic professionally to talk about plans for his audaciously scaled production of King Lear, which would open in fall 2006 with Stacy Keach in the title role. Falls says now it was a fortuitous meeting that he “stumbled into.”

At the time, “I didn’t know the specifics of Ana’s background or her ethnicity”—as far as he knew, she might have been Polish, or possibly Russian—“or much about her personally beyond this teacher-student relationship,” he recalls a little ruefully. “I had been working on this production for a long time in my head, and was eventually moving toward setting it amid the destruction of the former Yugoslavia. Ana hadn’t worked on anything that large-scale yet, but I thought—knowing she was from Europe and aware of the extravagance with which she can create exciting work—that I’d ask her to coffee to talk about the piece. And she said, ‘Well you know, I’m Serbo-Croatian. I lived through that. I was in Srpska in the early 1990s, at the height of the war.’ I was stunned.”

Kuzmanic’s passion and personal ability to provide detail on that decadent Lear, Falls says, “was the most exciting collaboration I’d ever had with a costume designer. She really was the principal collaborator I had. Ana was almost the co-creator of that piece.”

Kuzmanic never expected to find herself in Chicago.

“I really wanted to come to New York, because I guess it’s a cliché, but when you live in Europe, the most you know of America is New York.” But recruiters from Northwestern introduced her to Chicago’s theatre scene and persuaded her to come for a visit.

“They were wonderful, but I really wanted to go to New York,” she says, laughing about her wintertime visit to Chicago. “And I thought, ‘Oh, there’s nothing here—it’s so bare. There are no leaves. But somehow things happened, I came to Northwestern, and the next time I was here was early September. It was like night and day—I had found one of the most beautiful cities in the world. It was sunny. There were cultural happenings all the time—street concerts and jazz bars and all these things. I was like, ‘Wait, this is so different—I might like this.’”

Upon completing the MFA program in 2004, Kuzmanic considered trying out the West Coast and testing the film waters. “But I was lucky enough to start working here in Chicago. It was good for me. I really wanted to stay, except for the weather!’” she says with a grin. “But when I weigh it, weather [versus] all the opportunities and beautiful things this city offers? The choice was obvious.”

Kuzmanic’s first gig out of school was with the House Theatre of Chicago, a group that would enjoy a rapid rise to prominence over the next few years, thanks in part to high praise for Kuzmanic’s work on such shows as Dave DaVinci Saves the Universe, The Magnificents and the breakout 2007 hit The Sparrow, which earned rapturous reviews from prominent critics, enough to attract producers for a commercial transfer. “The House Theatre is my home,” Kuzmanic says—she would officially join the House’s ensemble in 2006.

But in the fall of 2004, the House was just opening its second season as a non-Equity company. “It was a show called Cave with Man. I don’t remember what the budget was, but you probably couldn’t buy decent shoes for that amount,” the designer jokes. “But nevertheless, it was so exciting and wonderful. I remember making just about everything, or heavily altering [commercial] pieces, because it was this invented world of cave people—I called the design ‘urban cave world.’ There were a lot of constructed pieces, skeletal pieces, zippers used as decoration.”

Nathan Allen, the House’s artistic director, was over the moon. He recalls encountering Kuzmanic’s work earlier that year at Northwestern’s MFA design showcase in a display called “The Birds.” “The costumes were birds—it was out there, kinetic. The costumes had a lot going on graphically; they implied physical action in a way that was better than just putting wings on somebody. They were colorful and beautiful and strange,” he remembers. “I was like, ‘Ahhh, you’re the costumer of my dreams!’”

Kuzmanic’s relationship with the House solidified, and showing her research and design ideas in the rehearsal room, Allen recounts, “she would inspire the whole room to be magical and imaginative, and nothing was impossible.”

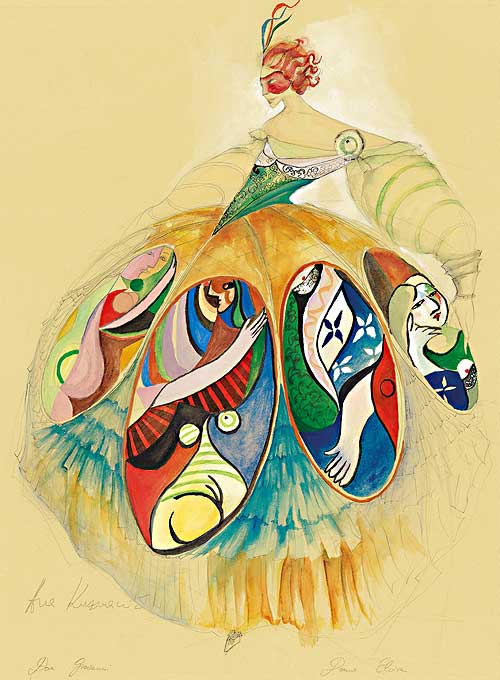

One of Kuzmanic’s two upcoming stage projects is Falls’s new staging of Mozart’s Don Giovanni for Chicago’s Lyric Opera. Her final drawings for the new staging cover the walls of her studio as we talk, representing what must be at least dozens of designs.

“I’ve been intensively designing it for the last year and a half,” she says. “Opera is a very different process. I’m always blown away by how evocative the music is. When I started working on Don Giovanni, just listening to the music with closed eyes—music is the character. The libretto is very important, but I listened to it many times without even reading the libretto, and I understood everything, I knew everything. I speak Italian a little bit, but it was really the music that blew me away.”

She pauses a moment, perusing the watercolor sketches on the wall. “The color palette pretty much came from music,” she says, then breaks into a wide grin. “It’s pretty exciting for me as an artist to even comprehend that.”

“There are directors who only work with certain designers,” Falls notes, “and I like to shake it up and really cast a play with designers the way you cast the actors. But I have to say, since 2005 or 2006, working with Ana, I really have gone to her most of the time. She’s one of the most extraordinary artists I’ve worked with in my career.”

Kuzmanic’s process begins with savoring her first reading of the text, “especially if I don’t know the work at all. I just read it,” she explains. “I probably don’t even think about costumes for quite some time. Reading it makes me feel a certain way.”

In the months leading up to rehearsals, and in consultation with her director, she begins her research, which can include “photographs, articles, anything that can give me insight into the world of the play. Sometimes I’ll do factual research into the playwright, the time he lived in, the time he set the play in.”

This, suggests Falls, is a remarkable understatement. “All designers will start accumulating imagery. But then Ana will discover some Russian Constructivist, or some Eskimo painter; she’ll bring in photographs of a German conceptual artist working on some project. She’ll bring in some bizarre detail,” he says.

“We were working on this O’Neill play”—Desire Under the Elms, which became one of Kuzmanic’s three Broadway turns, along with the Steppenwolf transfers of Tracy Letts’s August: Osage County and Superior Donuts—“and she’s finding images from P.T. Barnum, these close-ups of insects, this weird jar of insects. It had a psychological meaning, an emotional quality, that’s sort of surprising. It had absolutely nothing to do with making 1880s wool tights, but yet it somehow stimulates an emotional response for the work,” Falls elaborates. “And then she goes about editing.”

“She works the same way I do—associatively,” offers Tina Landau, who’s worked with Kuzmanic on three Steppenwolf shows: Superior Donuts, The Hot L Baltimore and last year’s U.S. premiere of Zinnie Harris’s sprawling war parable The Wheel. “Not that we don’t do research, but she and I also include our associations and intuition and dreams. On all of the shows we’ve done together, we’ve started by collecting images—hundreds and hundreds of images. Not pictures of clothes, but of anything that we relate to the world of the piece we’re creating.

“When we worked on The Wheel,” Landau adds, “Ana had so many amazing boards of images that even when we were in a huge conference room with a huge table, the images spilled over onto the chairs, the floor, everywhere. She never phones anything in. She’s there on the mat with you, wrestling it all out, and putting her whole soul into it.”

However, research and gathering materials is only one part of her process. “I also like to start drawing very early on,” Kuzmanic says. “I’ll go through series and series of sketches; each one of those drawing phases informs something—perhaps the silhouette, or just the jaggedness of the line. Some characters are jagged, some characters are smooth. Some have ridges and some are slippery.” She also likes to use collaging as a bridge between her research and her drawings. But even the final drawing, she points out, is “just the blueprint for the costume that gets built through fittings and finding fabrics.”

Kuzmanic’s other project this fall is an unusual opportunity to revisit some of those blueprints. Noah Haidle’s Smokefall, a Goodman world premiere staged last fall by Anne Kauffman, ended up on the year-end top-10 lists of many of the city’s critics (myself included), but the affectingly fractured look at family’s pull didn’t ignite as much interest as hoped. So the Goodman is giving it a remount just one year later, but moving the show from its studio space to the main stage.

“It’s an amazing play, but it’s written in such a way that it’s specific and abstract at the same time,” Kuzmanic says. “This is a great opportunity to make the production better. There are some changes I think are appropriate for the larger scale, and I’m excited to get another chance to do it. The gist of the design stays the same, but it’s an opportunity to make it clearer and better.”

Working on a new play, of course, offers a different way into her process. “If I’m working on a Shakespearean text, obviously it can be done in endless ways, but there is a very firm starting point—usually a director comes to the table with a very clear idea of the time or place. But if it’s a new play, often there are changes happening all the time as you go,” Kuzmanic notes.

With playwright Haidle in the room last fall, “I remember when there was this kind of quick-change moment that I was trying to figure out, and Noah was like, ‘Oh, I’ll just write in a little bit of dialogue.’ And I was like, ‘No! I don’t want you to rewrite the play! We’ll solve this!’” she says. “But he was so wonderfully open and trusting—attached to what he wrote, but trusting of the process for everyone.”

There seem to be more potential projects this season that Kuzmanic’s not ready to talk about. “Some things you don’t want to jinx,” she figures. But there’s also her full-time teaching position. “It’s really gratifying constantly being around young people, young minds,” she says. “There’s a decent amount of classroom time, but there’s also a lot of out-of-the-classroom: mentoring, going to the student fittings, attending technical rehearsals for the student plays.”

As a Northwestern faculty member, Kuzmanic says, “My professional work is my ‘research.’ We do it; we don’t write books, we don’t write articles, but we put our art on stage. I feel that it’s important to be a practicing designer as you teach because you keep advancing your skill, your expertise, both on the practical level and then on the theoretical level as an educator. You need to do what you preach. On every project I do, I learn a lot, and then I transfer that to my students.”

Kuzmanic’s passion is enough to convince us how lucky we are she found theatre—or it her. “There’s something about the live theatre that I’m drawn to over and over again, and it’s because there’s no imprint. Every single rehearsal is different, every single performance is different, every single night is different,” she muses.

“And even my work keeps evolving, even through the performances. If I see the first performance and I see the last performance, I see nuances in the design, the way an actor maybe unbuttons a button. And I’m excited by that.”

Kris Vire is an associate editor and the chief theatre critic for Time Out Chicago.