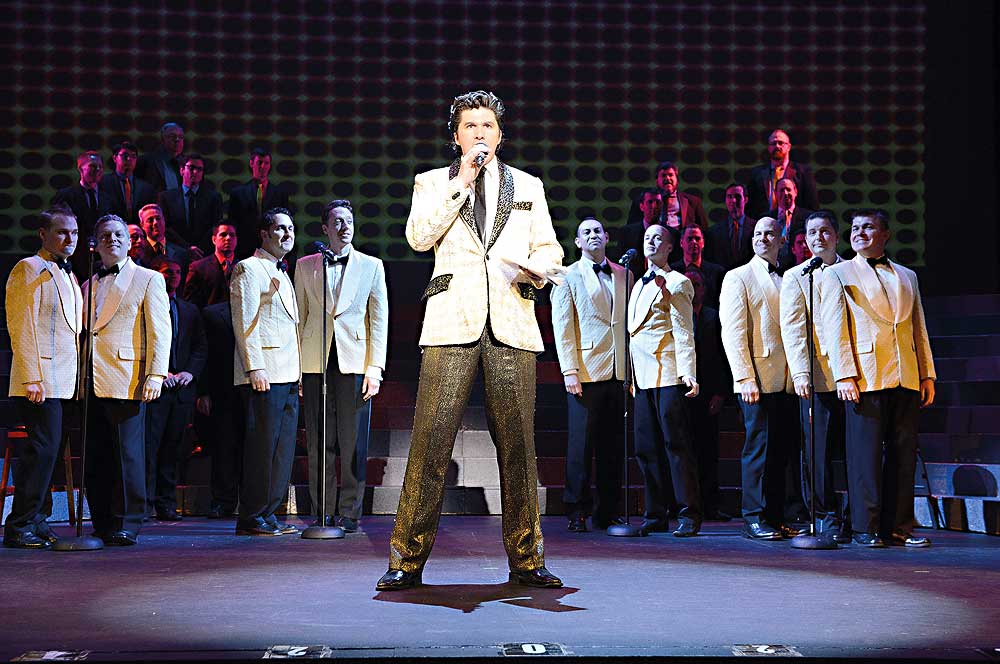

There he is: Louis Hobson, the well-praised and in-demand Seattle actor with the supple, high-baritone singing voice, the heartthrob looks and charisma to burn. In musicals-mad Seattle, he has played with distinction nearly every plum role on his bucket list—Che in Evita, Tony in West Side Story, Pippin in Pippin, Jean Valjean in Les Misérables.

Hobson went East to rack up more fans and kudos during a two-year Broadway stint playing a psychiatrist in the offbeat, Tony- and Pulitzer-winning musical Next to Normal. And he’s starting to score feature film roles, including a small but choice part in the upcoming Captain Fantastic, starring Viggo Mortensen.

For many actors, all this would portend a fulfilling stage and screen career.

But Hobson is a part of a bicoastal, build-it-yourself generation of multitalented multitaskers. And he’s a native member of a Pacific Northwest community that encourages (and can handsomely reward) upstart entrepreneurs.

So what’s fueling Hobson’s jets these days? An intense drive to operate behind the scenes, producing edgy, compact modern musicals. And that requires inventing a more productive, flexible and streamlined collaboration between the nonprofit and commercial sectors of musical-making.

“When I was in college, I always thought I’d be a director,” Hobson says, “and that maybe I’d act a little. But I got good at acting. And after a lot of experience working on shows, what really, really interests me now is producing.”

To that end, the triple-threat Hobson spent the last year as artistic director of Seattle’s Balagan Theatre, an energetic company formed in 2006 by manager/director Jake Groshong and Kaitie Warren, which has lately been developing and presenting au courant musicals (Ernest Shackleton Loves Me, ThanksKilling). Balagan shows often attract an enthusiastic, under-40 crowd of plugged-in young professionals, who are moving to the city in droves to work at booming high-tech and Internet businesses like Amazon (see update below).

“We know our identity as a theatre company,” declares Hobson. “We do things from the Broadway and Off-Broadway canon that appeal to our audience, like Urinetown and Spring Awakening. But our catalog is very limited—we need new works to add to it.”

With that in mind, Groshong and Hobson recently stepped down from their posts running Balagan on a day-to-day basis. (Danielle Franich is the company’s new executive director.) And they’ve created a for-profit entity, Indie Theatricals and Licensing (ITL), designed to realize their expansive plans. Simply put, the pair believes they can forge a more viable, more nimble way of generating and nationally disseminating fresh musicals by emergent young artistic teams—a way that will slash costs and provide a valuable platform for such works.

“Bringing things to Broadway isn’t necessarily the goal,” Hobson emphasizes. “There are regional theatres and small companies all over the country doing the kind of shows we’re working on.”

Ergo, Seattle. “Seattle has become a national hub for the development of new musicals,” Hobson asserts, pointing to the 5th Avenue Theatre, Seattle Repertory Theatre and the annual Festival of New Musicals at the Village Theatre as excellent laboratories for new musicals. He also touts the rich, expanding pool of musical-theatre talent in the area, and the region’s receptive, adventurous theatregoers. “I think the scene here is about to crack open,” Hobson predicts. “And I want to be at the center of whatever new is happening—wherever that is.”

The experiences, artistic contacts potential backers and other resources he’s drawing on for this venture, Hobson acknowledges, have come primarily through his acting gigs.

Fresh out of an undergrad theatre program at Tacoma’s Pacific Lutheran University, the Puyallup, Wash., native quickly came to the attention of 5th Avenue’s eagle-eyed executive producer and artistic director David Armstrong.

“Louis had all the skills—he’s a fantastic singer, a very good actor—and that was clear from the very beginning, when we put him in the chorus of Gypsy,” remembers Armstrong. “There’s something so fascinating about Louis. You want to watch him; there’s a complexity that comes through in every character he plays. It’s that ‘it’ factor. Either you have it or you don’t.”

Hobson’s breakout role at 5th Avenue was in an exhilarating revival of the echt-hippie musical Hair. He was a physically lithe, magnetic and critically lauded Claude to the Berger of 5th Avenue alum (and future Broadway headliner) Cheyenne Jackson.

Jamie Bernstein, a writer/broadcaster and a daughter of the late composer Leonard Bernstein, later caught Hobson’s 2007 performance in West Side Story at the same theatre. She recalls thinking, “He was the best Tony I’d ever seen! Louis has that precious combination of virility, sensitivity and good looks that creators and audiences alike look for in a musical-theatre actor—and then he sings, and everyone melts for good.”

Bernstein subsequently recommended Hobson to composer/lyricist Jeffrey Stock and writer Marc Acito, who cast him as the romantic lead in the 2014 run of their musical A Room with a View, also at 5th Avenue.

An intensely analytical and detail-oriented performer, Hobson could try a director’s patience in rehearsals, according to Armstrong and others. “I could be difficult to work with sometimes when I was younger,” Hobson admits. “I was reinventing the wheel all the time, and I’ve learned to temper that. But I don’t want to leave any stone unturned while I’m trying to fulfill a writer and director’s vision. It’s a collaborative art form, and you have to be up for the process.”

But it was the producer’s process that increasingly intrigued Hobson. Offstage, he closely observed Armstrong’s savvy management of shows for his company’s 25,000 season subscribers-—familiar hits like Cabaret and West Side Story, alongside Broadway-bound new tuners like the Tony-honored Hairspray and Memphis. “I saw how much was involved in that job, and how David was putting together the right people to create good shows his audience really wanted to see, and how he made those shows exciting for them.”

During the 2009–11 run of Next to Normal, Hobson also avidly studied the backstage maneuvers of prominent Broadway producer David Stone (a force behind Wicked, If/Then and other hits). “I was the guy in the cast who was always asking David Stone about the grosses, and how much a billboard ad cost, and when the deadline for the Pulitzers was,” Hobson reports with a smile. “I saw how he would put together these dream teams of artists, and how important that was.” Hobson recalls asking Stone if he could pick his brain for a few minutes about his ideas for producing new shows—and the conversation turned into a two-hour, one-on-one master class.

After Next to Normal closed, Hobson drew positive attention in featured parts in several other new (but short-lived) Broadway musicals, including Leap of Faith and Bonnie and Clyde. But in 2013, he and his talent agent wife Noreen decided to head back to the Seattle area with their three young children.

The move home wasn’t a retreat, Hobson stresses. It was a chance to raise their kids in a familiar community, around family. And it provided an opportunity to plunge into producing, putting his contacts and experiences to use in a hospitable, more affordable theatrical environment.

Hobson soon had a place to experiment with the kind of accessibly offbeat, adult-oriented musicals that make up in hip appeal, to an under-40 audience, what they lack in big-budget razzle-dazzle. His models? Dark-horse national successes like Spring Awakening, Urinetown and The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee.

He found a kindred spirit in Groshong at the Balagan, where the duo proceeded not only to introduce unconventional new tuners but to mount more established shows like Jerry Springer: The Opera, and to incubate a slate of adventurous projects, including a musical version of the film Citizen Ruth and a bio-musical with Chekhovian overtones about the late Seattle rocker Kurt Cobain, titled Nirvanov.

Hobson says he’s learned a lot about helping to secure the stage rights of screenplays (which musicals are increasingly based on), and he’s made inroads with commercial theatre investors for enhancement money. But he and Groshong say they’ve concluded that the standard model for developing smaller, sophisticated and commercially viable shows is “not sustainable.”

Enter Indie Theatricals Licensing: Hobson believes the operation could cut the risk of relying on individual backers for particular shows by serving as a revolving “venture capital fund” for new material—and that that support can be bolstered by securing a financial stake in any future profits and licensing fees the shows ITL develops may generate later.

The details are still rough, but Hobson and Groshong tentatively plan to be involved in the development of 50 new musicals over the next five years, on a tight budget of about $1.5 million.

That’s a lot of properties to hatch. But Hobson says they already have some involvement in 25 shows in various phases of incubation. And he maintains their approach will be lean, flexible and economical. With a small administrative staff, using both union and non-union performers, they are able to quickly put together readings, then workshops and labs, for the most promising shows at a fraction of the cost in New York or at larger regional theatres. Ideally, each year two or three of the best shows would receive full professional productions in Seattle venues. Balagan would be the nonprofit producing arm of the venture.

Most imminently, the Seattle premiere of the Off-Broadway musical Dogfight, adapted from the movie by the rising team of Benj Pasek, Justin Paul and Peter Duchan, is opening this October at ArtsWest Playhouse, in a co-production with Balagan. Later this season, Balagan will stage the world premieres of Citizen Ruth and Make Me Bad, billed as a “gritty, sexy psychological thriller.”

Will all these plans come to fruition? So far, Balagan’s producing record has been good, with some hits and a few misses. Some planned shows have fallen by the wayside due to a withdrawal of backing or other complications. Of course, Hobson isn’t the first to envision a better cultivation and delivery system for new musicals—and his intensity can sometimes come across as brashness and overconfidence. But the passion and laser-focus attention he brings to acting are equally evident when he’s playing producer.

Meanwhile, rest assured that Hobson-the-actor won’t be fading away. In fact, he’ll be both developing and appearing in “a new immersive theatrical experience” titled For Madmen Only, which Hobson compares to the New York hit Sleep No More.

He projects that Balagan will premiere that show some time in the next year. What’s it about? Hobson allows that it’s “best described as a rock burlesque cabaret based on Hermann Hesse’s novel Steppenwolf, set to the music of the rock duo The Dirty Bandits.”

Rave on.

Story Update: On September 19, 2014, the Balagan Theatre suddenly announced it was shutting down. The board of directors cited financial difficulties due in part to rapidly mounting debts, related in part to higher costs of Balagan producing without its own venue. (The company’s former landlord, Seattle Central College, has reclaimed the Erickson Theatre for its own programming.) Hobson said he was aware of fiscal problems, but had been raising funds for Indie Theatrical co-productions with Balagan, and was surprised and “distressed” by the news. He and Groshong said they still plan to present the slated Balagan musicals Citizen Ruth and Make Me Bad, and are looking into other venues. News story here.

Misha Berson is theatre critic for the Seattle Times and a regular contributor to this magazine.