Reviewing A Lovely Sunday for Creve Coeur, one in a long string of Tennessee Williams’s later flops, New York Magazine critic John Simon suggested in 1979 that “the kindest thing to assume is that Williams died shortly after completing Sweet Bird of Youth”—in other words, 20 years earlier. While Simon’s acidic tone was characteristically outrageous, he was voicing what many critics at the time were thinking: that something had gone wrong with Williams circa 1960. This impression was not solely based on aesthetics but was also informed by the playwright’s personal decline over these years, into substance abuse and erratic behavior. Perhaps even fans could not be blamed for wishing he had made his final exit when he was regarded as Broadway’s greatest poet, rather than ending up as a lonely 71-year-old man found dead on the floor of a Manhattan hotel room after an all-night binge of boozing and pill-popping.

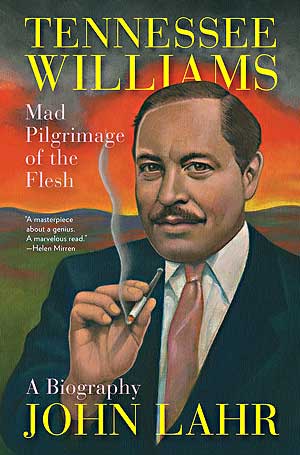

Williams’s less-than-dignified end has inevitably clouded many assessments of his legacy, despite the enduring esteem for most of his work between The Glass Menagerie in 1945 and The Night of the Iguana in 1961. The lack of a major biography that might offer more context for understanding those later years has only made the problem worse. Lyle Leverich’s Tom: The Unknown Tennessee Williams, though widely acclaimed upon its publication in 1995, only covers the playwright’s life up through the opening of Menagerie, when he was 34. At last, with the long-awaited arrival of John Lahr’s Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh, a fuller account of the playwright’s entire life can finally emerge.

Anyone hoping for a sunnier picture of that life from Lahr, though, will be disappointed. This is a fairly depressing book. But it is also so bracingly truthful and exhaustively detailed about its subject that, for better or worse, it is a must-read for anyone seriously interested in this iconic American artist.

Initially, Lahr—until recently the longtime drama critic for the New Yorker—was supposed to write a sequel to Leverich’s book after that author died in 1999. But he eventually chose to produce his own stand-alone work, drawing in part on Leverich’s collected research and resources. Still, Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh might as well be called Tom: Part Two, since only the first 60 of its 600 pages deal with the years before 1945, a choice reflecting Lahr’s greater interest in Williams’s career than in his origins—especially in the story of how he lost his way after achieving so much.

But if Williams’s early years are skimmed over here, his family history is always in the background as something to be escaped or atoned for. Lahr closely hews to Leverich’s definitive telling of Williams’s relationship with his sister Rose (and of her horrific lobotomy operation in 1943), but he also shows how much she haunted her brother’s plays far beyond her surrogate, Laura, in Glass Menagerie. The legacy of Williams’s parents—his puritanical mother and alcoholic, philandering father—also resurfaces throughout his work, Lahr claims, through the ever-present conflict between “indulgence and commitment, sensuality and soul.” Their repressive regime stunted Williams’s emotional and sexual development until independence, enabled by the success of his writing, finally liberated him to discover himself.

For Lahr, the confluence of Williams’s first hit play with the embrace of his sexuality marked a profound turning point, when “his writing became both a conscious and unconscious attempt to chart the unlearning of repression.” Where Menagerie “broadcast Williams’s romantic self,” in his next plays—especially A Streetcar Named Desire (1947) and Summer and Smoke (1948)—he “brought his own promiscuity and the forces that drove it into the center of the drama.”

The constant foregrounding of sexuality in Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh—the phrase comes from a 1945 short story—risks overshadowing Williams’s artistry at times. More space is devoted to his carnal exploits than to his theatrical and literary ideals. But Lahr, through frequent quotations from diaries and letters, succeeds in showing how central Williams’s struggles with his desires and relationships became to his work. “To give life to his characters,” he argues, “Williams preyed on himself—drawing on drugs and promiscuity to engineer the extravagant conversion of despair into art.” Indeed, even during his darkest periods, Williams made time almost every morning to write, one reason that he was so extraordinarily prolific.

Lahr also explores Williams’s simultaneous need for and fear of intimacy, and he rightly treats Williams’s 14-year relationship with Frank Merlo—his primary companion and on-and-off secretary through the first half of his career—as the de facto marriage of his life. While the marriage was a tumultuous one, wracked by betrayals and separations, Merlo’s death was clearly a key catalyst for the writer’s later decline.

Williams’s life and career suffered many other blows during the 1960s, as well. The decade’s social upheavals surprisingly worked against him, making him seem more relic than trailblazer. New theatrical movements (Theatre of the Absurd, political protest theatre) and younger dramatists (Edward Albee, Harold Pinter) eclipsed him at the cultural ramparts. The prudish social attitudes that gave his 1950s plays a thrilling sense of transgression were being swept away in the sexual revolution, robbing those works of what Lahr calls their initial “subversive romantic novelty.” One of the saddest ironies in Williams’s late life was his rejection in the post-Stonewall gay liberation movement by many who deemed his writing too timid on homosexual issues. (Williams, meanwhile, insisted he was “the founding father of the uncloseted gay world.”) As Tony Kushner tells Lahr in an interview, “The permission that Williams helped create sort of robbed him of a platform.”

Lahr does not blame the playwright’s decline on loss of talent, however, making strong cases for some of the late plays (The Gnadiges Fraulein and In the Bar of a Tokyo Hotel, in particular) and suggesting that the weaknesses of other works might have been mitigated with the input of some of the erstwhile collaborators who had helped make him great. Elia Kazan, who directed many of his 1950s plays, parted ways with him in 1960, but possibly even more detrimental was his firing of longtime agent Audrey Wood 10 years later. In doing so, says Lahr, Williams “was also releasing himself from any obligation to his past, including the obligation to be great.” Without the people he needed to keep him from spinning out of control, he was adrift—a state of mind that, in Lahr’s view, ultimately led him to the point of indifference and practically willing his own death. (One of Lahr’s most important discoveries is that Williams did not die by accidentally choking on a pill bottle cap, as initially reported, but from a barbiturate overdose.)

While Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh may not cheer Williams devotees, its clinical dissection of a great artist self-destructing is as compelling a drama as any Williams himself wrote. It also does the invaluable service of collecting and synthesizing all the research to date on the playwright (published and unpublished) into one chronological narrative. Perhaps no biography of such a complex person can be “definitive,” and Lahr’s stern judgments and idiosyncratic interpretations are sure to ruffle feathers. But his book will surely become, for now, the standard go-to life story of a writer for whom life and work were passionately—even if tragically—intertwined.

Garrett Eisler is Assistant Professor of Theatre Studies at Ithaca College and a former critic for Time Out New York and the Village Voice.