Is Wynn Handman the only producer to have ever fired Hal Prince? Did his singular vision for the American Place Theatre ultimately limit its success? Has he nonetheless earned a place in the American theatre pantheon, alongside his colleague and sometime competitor Joseph Papp?

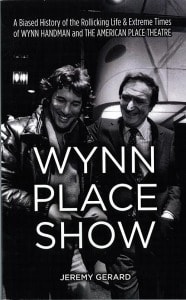

In Wynn Place Show, critic Jeremy Gerard makes a compelling case for “all of the above.” Any serious theatre junkie in New York from the late 1960s until the ’90s knows the American Place Theatre was one of the first artistic homes for writers, as well as a theatre that discovered some of the most important actors of our time.

When Handman sat down to write his manifesto in 1961, he was an acting student at Sanford Meisner’s Neighborhood Playhouse School of Theatre, where he so impressed his master that he was invited to begin directing there. Handman conceived the American Place Theatre as a reaction against what he considered the bland, mindless entertainment that predominated at the time. His theatre, he wrote, would restore high literary content to the stage. Lest anyone question the seriousness of his mission, he wrote it entirely in capital letters.

While this slim volume chronicles Handman’s theatre on an almost year-to-year basis, its history seems neither “rollicking” nor especially “extreme,” and but for a brief mention of a few formative early experiences, its subject’s personal life is largely missing. It may be that for Handman, like many who have run theatres, his work was his life.

Gerard makes much of the fact that New York critics often spoke more admiringly of “the idea” of American Place Theatre than about its more than 250 productions. But that doesn’t mean it wasn’t successful. During its early subscriptions-only era, it had more than 10,000 subscribers, while remaining focused on new works with an intellectual pedigree or ambition. As often as not, these came from poets and novelists (Robert Lowell, Anne Sexton, James Agee, Joyce Carol Oates) as much as from playwrights (Sam Shepard, Ed Bullins, María Irene Fornés, Ronald Ribman, Emily Mann). Handman also had a keen eye for monologists, like Eric Bogosian and John Leguizamo (who supplies the brief foreword to this book).

Handman had the great good fortune of securing a 30-year rent-free location in one of the first high-rise midtown developments incented by the city to include a theatre, on West 46th Street near Sixth Avenue, offering him a low-risk platform for his vision. And his genius at casting from the constant stream of new talent coming through the Neighborhood Playhouse meant that his audiences could count on compelling performances even when the material—ranging from the turgid to the surreal to the satirical—gave them whiplash. (That roster of talent included the likes of Dustin Hoffman, Richard Gere, Marian Seldes, Lois Smith, Morgan Freeman, Olympia Dukakis, Rip Torn, and so on.)

Eventually, though, external trends caught up with Handman’s operation, particularly the flight of major foundations from supporting the arts, and the growth and success of competing nonprofit subscription theatres in New York—companies whose missions gave them the latitude to venture into territory more commercial, and hence more lucrative, than Handman’s bailiwick. The final blow came when his landlord opted not to renew the theatre’s lease.

To his credit, Handman never abandoned his mission or compromised on his belief that America needed a place for his brand of theatre. Today, at 92, he continues to teach; rescued from the ashes of APT was its acclaimed Literature to Life educational program, which has continued at Young Audiences New York. Though he labored in the shadow of the flamboyant Papp for a good part of his career, Handman never coveted the limelight. “I admired what he did,” says Handman of his more famous contemporary. “I didn’t crave popularity. I said, ‘There’s mind in serious theatre.’ I wouldn’t have called my theatre the Public Theater…Joe was never as elitist as I was.”

Wynn Place Show is first and foremost a personal homage to a great man of the theatre by one of his greatest admirers. All the people quoted in the book share the belief that Handman was not only pivotal to their creative careers, but a rarity in the field as the most gentlemanly of producers. But what about Hal Prince? “Jonathan [Reynolds] quotes Hal saying I am the only person who ever fired him,” Handman recalls of failed negotiations to have Prince direct Reynolds’s play Yanks 3 Detroit 0 Top of the Seventh. This may not be strictly factual, but the point is that Prince, like most of those who dealt with Handman and his singular theatre, “never forgot it.”

Richard Stein attended the American Place Theatre in its heyday, including its memorable production of Sam Shepard’s Seduced.